Economy

Expert Examines Rising Trend Towards Corporate Procurement of Power in Sub-Saharan Africa

Renewable technologies are evolving at a rapid pace and there has been a dramatic decline in the costs associated with its procurement. This provides an opportunity for corporates to reap the benefits of procuring renewable energy directly from generators through the use of a power purchase agreement (corporate PPAs).

Corporate PPAs aim to provide corporates with lower or more stable electricity costs and grid reliability and can contribute significantly to their sustainability targets.

This is according to Mike Webb, Senior Associate in the Banking & Finance Practice at Baker McKenzie in Johannesburg.

He notes, however, that despite these benefits, corporate PPAs have struggled to take off in sub-Saharan Africa, commonly as a result of regulatory challenges. To guide corporates through numerous regulatory frameworks and legal developments governing this sector across Africa, Baker McKenzie’s new report, Opportunities for Corporate Procurement of Power in Sub-Saharan Africa studies corporate PPAs in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

“We have found that the key issue that obstructs the use of corporate PPAs in most of these markets is that a licence is required to either operate a power asset or sell power, or both. Most markets have a threshold where a licence is required, usually ranging between 100kW and 1000kW. Where projects exceed these thresholds, a license is required which can often be difficult to obtain. To overcome this, developers may structure the PPA as a hire-purchase agreement or lease,” explains Webb.

“However, in addition to potentially triggering unfavorable tax consequences (where the PPA becomes a contingent liability on the corporate’s books), these solutions carry enforceability risk and may not pass a lender’s bankability requirements.

“It’s worth noting that there are currently no licence requirements in Senegal and Mozambique and the threshold in Uganda for a licence is 2000 kW,” he notes.

“In addition to licence requirements, most jurisdictions require approval from the local distribution network operator to install an on-site power plant (e.g. rooftop solar PV). This approval can also be difficult to obtain and sometimes gets held up in months of administrative delays,” Webb explains.

Webb says that the good news is that as the energy transition slowly makes its way into sub-Saharan Africa, some utilities and regulators are showing signs of key market reforms that will enable more opportunities for corporate PPAs.

“For example, as of 1 September 2019, Namibia introduced a new energy policy that will allow the bilateral trading of power between generators and customers. In a small power market such as Namibia, the opportunities may be limited. However, it is expected that neighbouring countries, such as Zambia, could follow Namibia in this reform.

“A further key reform required in power markets to unlock opportunities of corporate PPA is net metering, where plants are able to supply unused power into the grid in return for a feed-in tariff. This is not available in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa and where it is available, such as South Africa, the tariff is often too low to enhance the economics of the project,” Webb explains.

Webb notes that as a result of strong resources, as well as poorly maintained and limited grid networks, sub-Saharan Africa has seen an increase in the roll out of mini-grids. Rapid technological development and operational efficiencies have made mini-grids a practical, cost effective and viable solution to electrify rural areas in Africa. The International Energy Agency estimates that at least 40% of new power connections in sub-Saharan Africa during the next decade will be provided by mini-grids. For example, Rwanda plans to provide over 90% of its electricity supply through mini-grids by 2024.

“The regulatory environment around mini-grids in Africa can be quite different depending on the country. Tanzania has fairly clear policies and regulations that favour mini-grids. Nigeria has issued regulation detailing the framework for the establishment of mini-grids. Uganda is currently developing a mini-grid framework with the support of various donor programmes. Similarly, Rwanda has been in consultation with private mini-grid companies in the development of their mini-grid framework,” he says.

Webb notes that a good sign that the power market is maturing is the increase in trading activity in the Southern Africa Power Pool (SAPP) in the last 18 months, which is beginning to show signs of a functional power pool. The SAPP currently serves more than 300 million people and has an available generation capacity of 67.19 GW. A total of 2,124 GWh was traded on the SAPP market during 2018, resulting in USD 106.6 million being exchanged on SAPP’s competitive market. Current operating members of SAPP include Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Namibia’s move to allow bilateral trading is expected to extend into the use of the SAPP. As the approval of the relevant utility is required for a person to become a participant in the SAPP, these signs are positive.

“In terms of sub-Saharan Africa countries to watch for corporate PPA opportunities, a recent Bloomberg New Energy Finance report noted that Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya stand out, based on positive economics and relatively accommodating regulatory systems. Senegal, Uganda and Rwanda, with increasing grid tariffs and reasonable momentum in renewable energy adoption, also offer opportunities. However, due to the small nature of the commercial and industrial power demand, the scalability of project portfolios appears to be limited,” he says.

“South Africa, being the most industrialised economy in Africa, is often considered a good starting point for corporate PPA development. Regulatory and policy uncertainty have been the main reasons why adoption has been relatively low. However, continued increases in Eskom supplied grid electricity tariffs has resulted in a notable increase in corporate PPAs over the last 18 months. This is expected to grow further once the Integrated Resource Plan is finalised and regulations are aligned,” he adds.

Economy

Flour Mills Supports 2026 Paris International Agricultural Show

By Modupe Gbadeyanka

For the second time, Flour Mills of Nigeria Plc is sponsoring the Paris International Agricultural Show (PIAS) as part of its strategies to fortify its ties with France.

The 2026 PIAS kicked off on February 21 and will end on March 1, with about 607,503 visitors, nearly 4,000 animals, and over 1,000 exhibitors in attendance last year, and this year’s programme has already shown signs of being bigger and better.

The theme for this year’s event is Generations Solution. It is to foster knowledge transfer from younger generations and structure processes through which knowledge can be harnessed to drive technological advancement within the global agricultural sector.

In his address on the inaugural day of the Nigerian Pavilion on February 23, the Managing Director for FMN Agro and Director of Strategic Engagement/Stakeholder Relations, Mr Sadiq Usman, said, “At FMN, our mission is Feeding and Enriching Lives Every Day.

“This is a mandate we have fulfilled through decades of economic shifts, rooted in a culture of deep resilience and constant innovation. We support this pavilion because FMN recognises that the next frontier of global Agribusiness lies in high-level technical exchange.

“We thank the France-Nigeria Business Council (FNBC), the organisers of the PIAS, and our fellow members of the Nigerian Pavilion – Dangote, BUA, Zenith, Access, and our partners at Creativo El Matador and Soilless Farm Lab— we are exceedingly pleased to work to showcase the true face of Nigerian commerce.”

Speaking on the invaluable nature of the relationship between Nigeria and France, and the FMN’s commitment to process and product innovation, Mr John G. Coumantaros, stated, “The France – Nigeria relationship is a valuable partnership built on a shared value agenda that fosters remarkable Intercontinental trade growth.

“Also, as an organisation with over six decades of transformational footprint in Nigeria and progressively across the African Continent, FMN has been unwaveringly committed to product and process innovation.

“Therefore, our continuous partnership with France for the success of the Paris International Agricultural Show further buttresses the thriving relationship between both countries.”

PIAS is one of the most widely attended agricultural shows, with thousands of people from across the world in attendance.

Economy

NEITI Backs Tinubu’s Executive Order 9 on Oil Revenue Remittances

By Adedapo Adesanya

Despite reservations from some quarters, the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) has praised President Bola Tinubu’s Executive Order 9, which mandates direct remittances of all government revenues from tax oil, profit oil, profit gas, and royalty oil under Production Sharing Contracts, profit sharing, and risk service contracts straight to the Federation Account.

Issued on February 13, 2026, the order aims to safeguard oil and gas revenues, curb wasteful spending, and eliminate leakages by requiring operators to pay all entitlements directly into the federation account.

NEITI executive secretary, Musa Sarkin Adar, called it “a bold step in ongoing fiscal reforms to improve financial transparency, strengthen accountability, and mobilise resources for citizens’ development,” noting that the directive aligns with Section 162 of Nigeria’s Constitution.

He noted that for 20 years, NEITI has pushed for all government revenues to flow into the Federation Account transparently, calling the move a win.

For instance, in its 2017 report titled Unremitted Funds, Economic Recovery and Oil Sector Reform, NEITI revealed that over $20 billion in due remittances had not reached the government, fueling fiscal woes and prompting high-level reforms.

Mr Adar described the order as a key milestone in Nigeria’s EITI implementation and urged amendments to align it with these reforms.

He affirmed NEITI’s role in the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) and pledged close collaboration with stakeholders, anti-corruption bodies, and partners to sustain transparent management of Nigeria’s mineral resources.

Meanwhile, others like the Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN) have kicked against the order, saying it poses a serious threat to the stability of the oil and gas industry, calling it a “direct attack” on the PIA.

Speaking at the union’s National Executive Council (NEC) meeting in Abuja on Tuesday, PENGASSAN President, Mr Festus Osifo, said provisions of the order, particularly the directive to remit 30 per cent of profit oil from Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs) directly to the Federation Account, could destabilise operations at the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) Limited.

Mr Osifo firmly dispelled rumours of imminent protests by the union, despite widespread claims that the controversial executive order threatens the livelihoods of 10,000 senior staff workers at NNPC.

He noted, however, that the union had begun engagements with government officials, including the Presidential Implementation Committee, and expressed optimism that common ground would be reached.

Mr Osifo, who also serves as President of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), expressed concerns that diverting the 30 per cent profit oil allocation to the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC), without clearly defining how the statutory management fee would be refunded to NNPC, could affect the salaries of hundreds of PENGASSAN members.

Economy

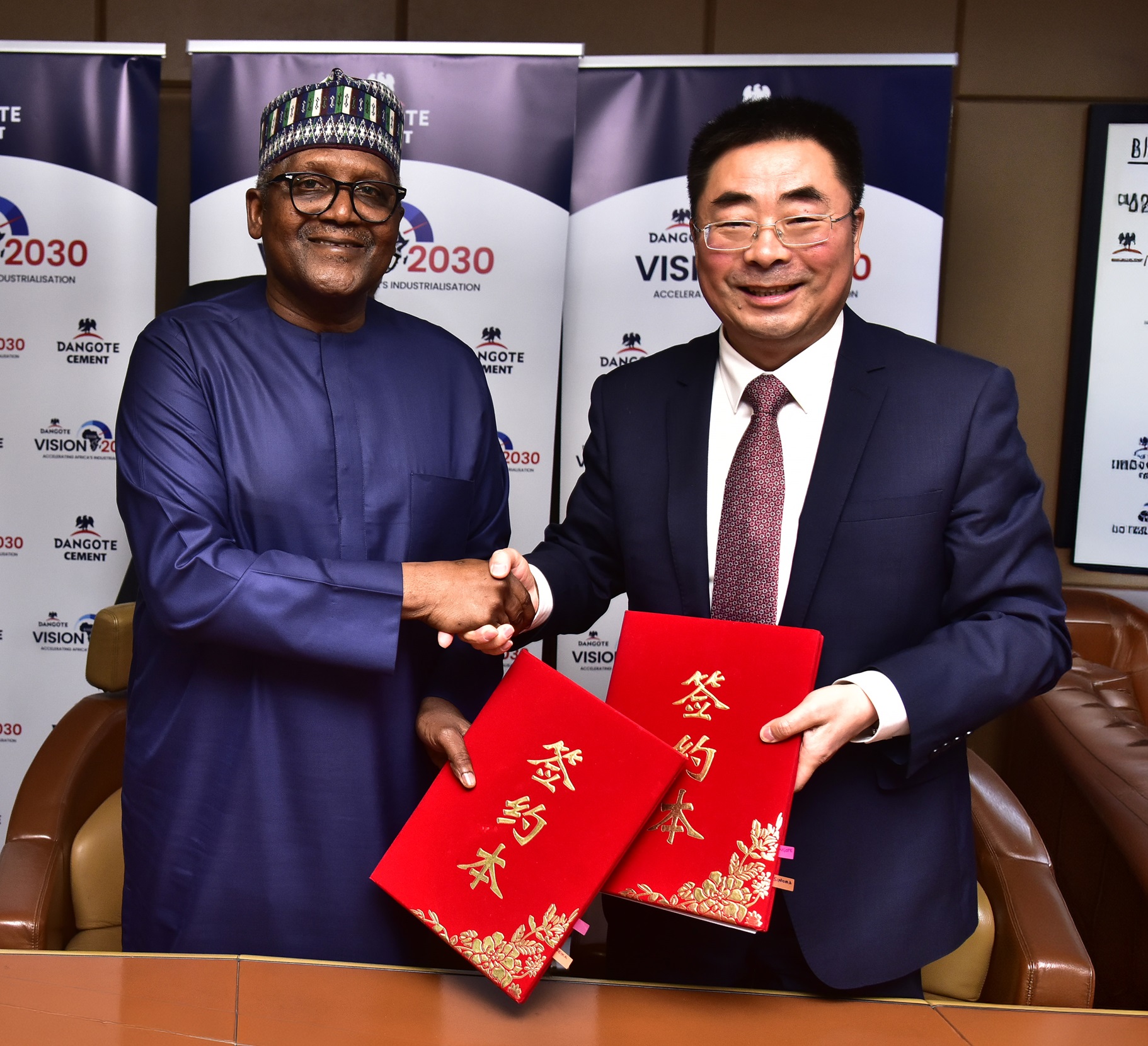

Dangote Cement Deepens Dominance, Export Activities With $1bn Sinoma Deal

By Aduragbemi Omiyale

To strengthen its domestic market dominance, drive its export activities, optimise existing operational assets and enhance production efficiency and capacity expansion, Dangote Cement Plc has sealed $1 billion strategic agreements with Sinoma International Engineering for cement projects across Africa.

The president of Dangote Industries Limited, the parent firm of Dangote Cement, Mr Aliko Dangote, disclosed that the deal reinforces the company’s long-term growth strategy and aligns with the broader aspirations of the Dangote Group’s Vision 2030.

According to him, Sinoma will construct 12 new projects and expand others for the cement organisation across Africa, helping to achieve 80 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) production capacity by 2030, while supporting the group’s overarching target of generating $100 billion in revenue within the same period.

Under the Strategic Framework Agreement, Sinoma will collaborate with Dangote Cement on the delivery of new plants, brownfield expansions, and modernisation initiatives aimed at strengthening operational performance across key markets.

The new projects include a new integrated line in Northern Nigeria with a satellite grinding unit, a new line in Ethiopia and other projects in Zambia/Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Sierra Leone and Cameroon. In Nigeria, Sinoma will also handle different projects in Itori, Apapa, Lekki, Port Harcourt and Onne.

The projects signal Dangote Cement’s sustained commitment to consolidating its leadership position within the African cement industry, while enhancing its competitiveness on the global stage.

Chairman of the Dangote Cement board, Mr Emmanuel Ikazoboh, during the agreement signing event in Lagos, explained that the new projects would enable the company to play a critical role in actualising Dangote Group’s Vision 2030.

The new projects, when completed, will increase Dangote Cement’s capacity and dominant position in Africa’s cement industry.

On his part, the Managing Director of Dangote Cement, Mr Arvind Pathak, said the agreement reflects the company’s determination to grow its investments across African markets to close supply gaps and support the continent’s infrastructural ambitions.

According to him, Dangote Cement is committed to making Africa fully self‑sufficient in cement production, creating more value and linkages, leading to increased economic activities and a reduction in unemployment.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn