Economy

Oil Prices Slide as Angola’s OPEC Exit Raises Worries

By Adedapo Adesanya

Oil prices dropped on Thursday after Angola said it would exit the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Brent crude futures went down by 31 cents to close at $79.39 a barrel while the US West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude futures fell by 33 cents to $73.89 a barrel.

Angola’s oil minister, Mr Diamantino Azevedo, said on Thursday that the country’s membership in OPEC was not serving its interests.

In his words, “Our role in the organization was not deemed relevant. It was not a decision made lightly — the time has come.”

The exit raises questions about the producer group’s efforts to support prices by limiting global supplies.

Angola’s exit will shrink OPEC to 12 nations at a time when it’s struggling to shore up prices, which have lost almost 20 per cent in the past three months.

The Saudi Arabia-led producer group in recent months has been rallying support to deepen output cuts and boost oil prices.

The country’s clash with OPEC’s leadership emerged in June, when a deal that awarded a higher production target to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) forced Africa’s second largest oil producer to accept a reduced limit for 2024 that certified its fading abilities.

Angola produces around 1.1 million barrels per day, compared with 28 million barrels per day for the whole group.

Market analysts say since it is one of the smallest producers and its departure may have a limited impact on global supplies.

Several members have quit OPEC in recent years, for different reasons from Indonesia to Qatar and most recently, Ecuador.

Separately, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) said its crude output rose to a record 13.3 million barrels per day last week, up from the previous all-time high of 13.2 million barrels per day.

Recent attacks carried out in support of Palestinians by Yemeni Houthi militant group on vessels headed towards Israeli ports have forced major maritime carriers to steer clear of the Red Sea, causing global trade disruptions.

About 12 per cent of global trade, including 30 per cent of global container traffic, passes through the Red Sea, meaning that delays there can potentially affect fuel prices as well as the availability of various commodities and electronics.

Many companies have already halted shipping in the Red Sea and at the Suez canal. Four of the world’s five largest container-shipping companies, namely Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd, CMA, CGM and MSC, have paused or suspended their services in the Red Sea, the route through which traffic from the Suez Canal must pass.

Economy

LIRS Urges Taxpayers to File Annual Returns Ahead of Deadline

By Modupe Gbadeyanka

All individual taxpayers in Lagos State have been advised to file their annual tax returns ahead of the March 31 deadline.

This appeal was made by the Lagos State Internal Revenue Service (LIRS) in a statement issued by its Head of Corporate Communications, Mrs Monsurat Amasa-Oyelude.

The notice quoted the chairman of LIRS, Mr Ayodele Subair, as saying that timely filing remains both a constitutional and statutory obligation as well as a civic responsibility.

The statutory filing requirement applies to all taxable persons, including self-employed individuals, business owners, professionals, persons in the informal sector, and employees under the Pay-As-You-Earn (PAYE) scheme.

In accordance with Section 24(f) of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Sections 13 &14(3) of the Nigeria Tax Administration Act 2025 (NTAA), every individual with taxable income is required to submit a true and correct return of total income from all sources for the preceding year (January 1 to December 31, 2025) within 90 days of the commencement of a new assessment year.

“Filing of annual tax returns is not optional. It is a legal requirement under the Nigeria Tax Administration Act 2025. We encourage all Lagos residents earning taxable income to file early and accurately.

“Early and accurate filing not only ensures full adherence with statutory requirements, but supports effective monitoring and forecasting, which are critical to Lagos State’s fiscal planning and long-term sustainability,” Mr Subair stated.

He further noted that failure to file returns by the statutory deadline attracts administrative penalties, interest, and other enforcement measures as prescribed by law.

To enhance convenience and efficiency, all individual tax returns must be submitted electronically via the LIRS eTax portal at https://etax.lirs.net. The platform enables taxpayers to register, file returns, upload supporting documents, and manage their tax profiles securely from anywhere.

In keeping with global best practices, Mr Subair reiterated that LIRS continues to prioritise digital tax administration and taxpayer support services. He affirmed that the LIRS eTax platform is secure and accessible worldwide. Taxpayers requiring assistance may visit any of the LIRS offices or other channels.

Economy

NNPC Targets 230% LPG Supply Surge to 5MTPA Under Gas Master Plan 2026

By Adedapo Adesanya

The Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) Limited has said the Gas Master Plan 2026 targets over 230 per cent scale-up of Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) supply from 1.5 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) to 5 MTPA this year.

The Executive Vice President for Gas, Power and New Energy at NNPC, Mr Olalekan Ogunleye, unveiled the strategic direction of the NNPC Gas Master Plan 2026, outlining an aggressive expansion drive to position Nigeria as a regional and global gas powerhouse.

Mr Ogunleye delivered the keynote address at the 2026 Lagos Energy Week, organised by the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE), where he detailed plans to accelerate gas development, deepen infrastructure and significantly scale domestic supply.

According to him, the Gas Master Plan targets a scale-up of LPG or cooking gas supply from 1.5 MTPA to 5 MTPA, alongside expanded feedstock for Mini-LNG and Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) projects.

“The NNPC Gas Master Plan 2026 is a blueprint to unlock Nigeria’s vast gas potential and translate it into tangible economic value,” Mr Ogunleye said.

He added that the strategy would also drive exponential growth in Gas-Based Industries, GBIs, strengthening local manufacturing, fertiliser production and power generation.

“Our renewed focus is on turning abundant gas resources into inclusive economic growth and improved quality of life for Nigerians,” he stated.

Mr Ogunleye said the plan aligns with the Federal Government’s Decade of Gas initiative and the presidential production targets of achieving 10 billion cubic feet per day by 2027 and 12 BCF/D by 2030.

Industry leaders at the event, including executives from Chevron Corporation, Esso Exploration and Production Nigeria Limited, Midwestern Oil and Gas Company Limited, Abuja Gas Processing Company and Shell Nigeria Gas, commended the plan and praised Ogunleye’s leadership in driving implementation excellence.

The new blueprint signals NNPC’s determination to anchor Nigeria’s energy transition on gas, leveraging infrastructure expansion and domestic utilisation to consolidate the country’s status as Africa’s largest gas reserve holder.

Economy

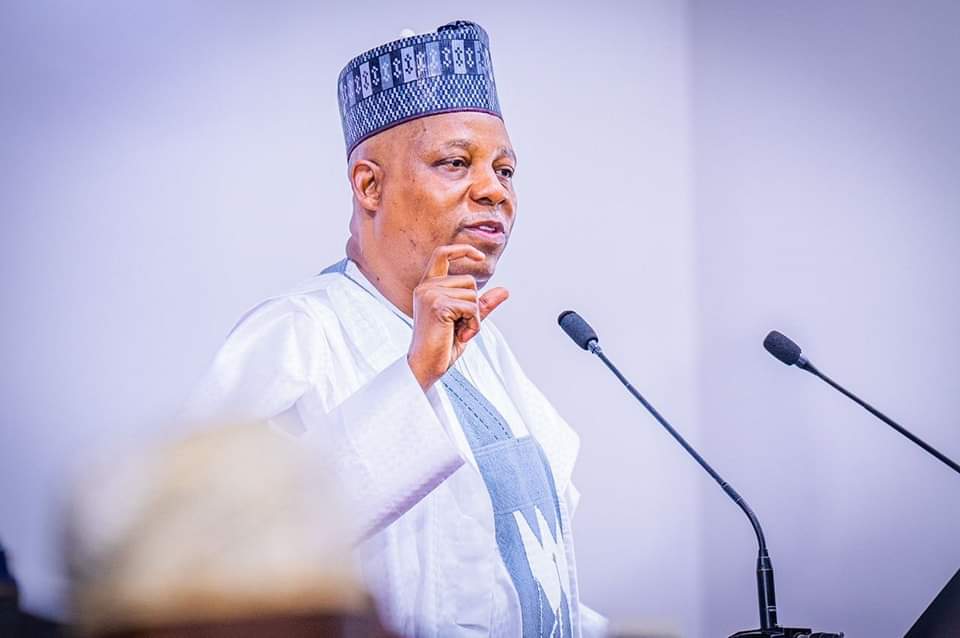

Shettima Blames CBN’s FX Intervention for Naira Depreciation

By Adedapo Adesanya

Vice President Kashim Shettima has attributed the Naira’s recent depreciation to the intervention of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) in the foreign exchange (FX) market, stating that the currency could have strengthened to around N1,000 per Dollar within weeks if the apex bank had allowed market forces to prevail.

The local currency has dropped over N8.37 on the Dollar in the last week, as it closed at N1,355.37/$1 on Tuesday at the Nigerian Autonomous Foreign Exchange Market (NAFEM), after it went on a spree late last month and into the early weeks of February.

However, speaking on Tuesday at the Progressive Governors’ Forum (PGF), Renewed Hope Ambassadors Strategic Summit in Abuja, the Nigerian VP said the intervention was to ensure stability.

“In fact, if not for the interventions by the Central Bank of Nigeria yesterday, the 1,000 Naira to a Dollar we are going to attain in weeks, not in months. But for the purpose of market stability, the CBN generously intervened yesterday.

“So, for some of my friends, especially one of our party leaders who takes delight in stockpiling dollars, it is a wake-up call,” the vice president said.

He was alluding to CBN buying US Dollars from the market to slow down the rapid rise of the Naira.

Latest information showed that last week, the apex bank bought about $189.80 million to reduce excess Dollar supply and control how fast the Naira was gaining value.

The move was aimed at preventing foreign portfolio investors from exiting Nigeria’s fixed-income market, as large-scale sell-offs could heighten demand for US Dollars, intensify capital flight, and exert further pressure on the exchange rate.

Amid this, speaking after the 304th meeting of the monetary policy committee (MPC) of the CBN on Tuesday, Governor of the central bank, Mr Yemi Cardoso, said Nigeria’s gross external reserves have risen to $50.45 billion, the highest level in 13 years.

This strengthens the country’s foreign exchange buffers, enhances the apex bank’s capacity to defend the Naira when needed, and boosts investor confidence in the stability of the Nigerian FX market.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn