Feature/OPED

Election, Debate and the Need for Attitudinal Change

By Omoshola Deji

Debate is a vital, far-reaching and inexpensive means of campaigning and earning the voters admiration before election. It is identical to an interview session wherein the employer (electorates) assess the job seekers (contestants) suitability for the job. In developed nations, candidates save debate dates and prioritize attendance over other political activities or duties. Participating in debates is not based on self-determined conditions or wish. It is an essential responsibility. Absence at debates is a political suicide that can break the backbone of a candidate’s political career or end it. In such climes, reeling out manifestoes, the implementation methodology and facing public scrutiny is not construed as rendering favour to the people, but a solicitation of it. The reverse is the case in Nigeria.

After returning to democratic rule in 1999, our political consciousness has increased, but our political culture remains undeveloped. On political consciousness, individuals were once upon a time begged to contest for top political offices, but people now struggle hard to become Councillors. Lagging behind, our political culture has not developed swiftly as the consciousness. Candidates still discount political debates since participation and performance are inconsequential on election results. The electorates are responsible for this. Top on most persons’ candidate suitability checklist is ethno-religious connection and political affiliation. Debate and manifesto assessment is rated unimportant. This emboldens candidates, especially that of the dominant parties to dishonour debate invites. Such is the case witnessed at the just concluded Presidential debate organized by the Broadcasting Organizations of Nigeria (BON) and the Nigeria Elections Debate Group (NEDG).

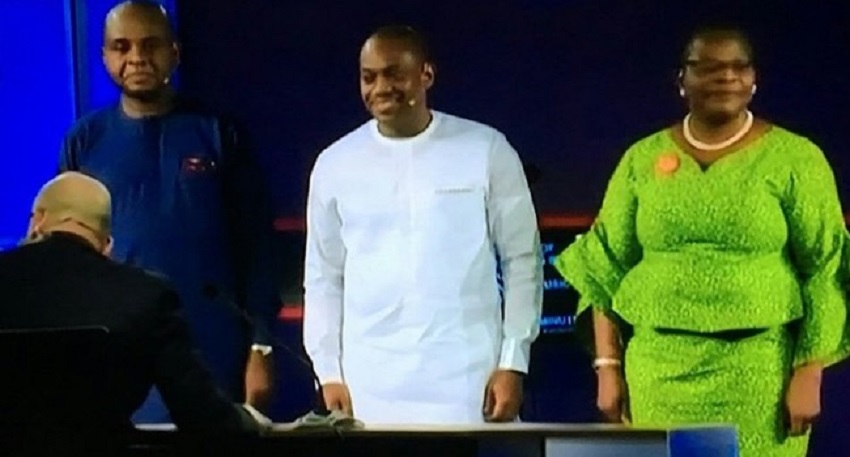

Five presidential candidates, out of over seventy, were opaquely selected to debate. The five selected candidates are Obi Ezekwesili of the Allied Congress Party of Nigeria (ACPN), Fela Durotoye of the Alliance for New Nigeria (ANN), Muhammadu Buhari of the All Progressives Congress (APC), Atiku Abubakar of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), and Kinsley Moghalu of the Young Progressive Party (YPP). Ezekwesili, Durotoye and Moghalu turned up for the debate, Atiku put in an appearance, but declined participating, in fulfilment of his earlier alert that he would not participate if Buhari does not show up.

Atiku’s refusal to debate diminished the admiration his visit to the United States earned him. Nigerians were initially impressed he returned from the US few hours to the debate and made it to the venue on time. His inner circle and political strategists miskicked the ball when they made Buhari’s decision determine their action. Atiku contends that he withdrew from the debate because Buhari “who is at the helm of affairs of the nation is not present to defend himself or his policies”. This argument holds no water. What if Buhari is a first term contestant and not an incumbent seeking re-election?

Atiku shouldn’t have stormed out of the debate without participating. His action mirrors an applicant excluding himself from a job interview because a particular candidate is not present. Such action will, almost certainly, not earn the applicant the job. In this case, Atiku had the confidence to act in such manner because the employer (the electorates) has not made debating a winning determinant like the other employers in developed nations. Avoiding the debate because Buhari is absent is a disregard to the Nigerian populace who have stayed tuned to hear how Atiku intends to ‘get Nigeria working again’. It is also an unnecessary attack on Buhari’s right of choice. Buhari’s absence shouldn’t make Atiku desist from presenting his policies to the populace. Atiku took such action because non-participation in debates has no effect on electoral votes.

Atiku’s seems to have acted based on concerns other than Buhari’s absence. He apparently left to avoid being humiliated by other candidates. He may also consider debating with presidential candidates who can’t earn half a million votes a waste of time and disrepute to his person. Such reasoning and ego is prevalent in our polity. Moghalu, Ezekwesili and Durotoye’s weak political structure humbled them to participate. They would have most likely behaved like Atiku or Buhari if they were in their shoes.

Nonetheless, it is un-presidential for a president not to attend a presidential debate. Buhari lost a golden opportunity to convince Nigerians that he is fit to continue being President. Avowing that busy official and political schedules clashed with the debate is an untenable excuse, especially when many people are casting doubt on his mental ability and had predicted his non-participation.

Defending Buhari’s absence is encouraging wrongdoing. Shuttling the country to campaign is good, but debating is a better means of reaching more people, including the electorates, Nigerians in diaspora, and the international community. Other programs should have been postponed if the President considers it important to take part in the debate. If it were to be his personal electoral duties such as the submission of nomination form, collection of return certificate, or swearing-in ceremony, would he be absent?

The APC and Buhari’s inner circle allegedly prevented him from participating in the debate in order not to further expose his intelligence deficiency. The Aso Rock cabal is handling Buhari like the late President Yar’Adua. They are encouraging him to stay in office despite being aware of his deteriorating health. One can only pray that Buhari doesn’t end like Yar’Adua because of the greed of a few persons. Buhari means well, but his ability to function effectively can’t increase, it will decrease further as he aged.

Atiku unrelentingly challenging Buhari to debate – and the President’s abysmal performance at public functions lately – made his team prevent him from attending the debate. This decision is irrational, but wise. Buhari lacks communication skills and the ability to speak on crucial issues offhand. He would have probably made a mockery of himself if he had debated with persons like Moghalu and Ezekwesili.

Aside Buhari and Atiku, Presidential candidates will continue to boycott debates because majority of the voting population don’t cherish or know the importance of debates. The real Nigerian voters are largely the less educated people comprising of artisans, traders and thugs who neither watch television nor surf the web. Most of those clamouring for debate are the (social media) elites who do not have a voter’s card. As long as this trend persists, candidates will continue to shun debates and rather rely on handing out freebies and stomach infrastructure to win elections.

The three candidates respected Nigerians by participating in the debate, but Nigerians won’t reward them with their votes. Debate and brilliancy don’t win elections in Nigeria, political structure and financial strengths do. Moghalu performed better than Ezekwesili and Durotoye, but the three are all winners, the losers are the absentees – Buhari and Atiku. But then, the obvious truth is that one of the absentees will eventually win the election. Other political parties are too syndicated or ethnic fixated to win presidential election in a plural nation like Nigeria. The less dominant parties must unite into a strong force, if they wish to beat the APC and PDP in 2023. 2019 Presidency belongs to either APC or PDP.

Nevertheless, Nigerians need a robust party other than the dominant APC and PDP. The difference between both parties is that between six and half-dozen. Castigating one for the other is a waste of time as none of them can transform Nigeria.

We must also abolish all the socio-political anomalies that breed inefficiency. Anomalies have turned Nigeria into the Durkheim (1893) propounded state of anomie. If civil servants retire when they’re sexagenarian, why should a septuagenarian contest for President? If Nigerian graduates needs to serve the nation for one year before they can secure government jobs, why should school certificate be the minimum academic requirement to become President? So long as this anomaly remains unrectified, the less credible and incompetent ones would continue to occupy crucial leadership positions. The debilitating effect is a continuous rise in the political consciousness to grab power, and a political culture that accommodates underdevelopment, poverty and inefficiency.

Political Scientists need to further research factors that’ll compel candidates to participate in debates. Measures such as tackling illiteracy, encouraging political participation, and initiating a robust voter education exercise will improve Nigerians ability to assess candidate’s competence via debates. The ability to take decisions without primordial sentiments will usher in a high political standard that’ll transform the political culture. Attitudinal change is urgently needed to sanitize the monetized political system and redefine the rules guiding the conducts of elections and debates.

Omoshola Deji is a political and public affairs analyst. He wrote in via mo******@***oo.com

Feature/OPED

How Christians Can Stay Connected to Their Faith During This Lenten Period

It’s that time of year again, when Christians come together in fasting and prayer. Whether observing the traditional Lent or entering a focused period of reflection, it’s a chance to connect more deeply with God, and for many, this season even sets the tone for the year ahead.

Of course, staying focused isn’t always easy. Life has a way of throwing distractions your way, a nosy neighbour, a bus driver who refuses to give you your change, or that colleague testing your patience. Keeping your peace takes intention, and turning off the noise and staying on course requires an act of devotion.

Fasting is meant to create a quiet space in your life, but if that space isn’t filled with something meaningful, old habits can creep back in. Sustaining that focus requires reinforcement beyond physical gatherings, and one way to do so is to tune in to faith-based programming to remain spiritually aligned throughout the period and beyond.

On GOtv, Christian channels such as Dove TV channel 113, Faith TV and Trace Gospel provide sermons, worship experiences and teachings that echo what is being practised in churches across the country.

From intentional conversations on Faith TV on GOtv channel 110 to true worship on Trace Gospel on channel 47, these channels provide nurturing content rooted in biblical teaching, worship, and life application. Viewers are met with inspiring sermons, reflections on scripture, and worship sessions that help form a rhythm of devotion. During fasting periods, this kind of consistent spiritual input becomes a source of encouragement, helping believers stay anchored in prayer and mindful of God’s presence throughout their daily routines.

To catch all these channels and more, simply subscribe, upgrade, or reconnect by downloading the MyGOtv App or dialling *288#. You can also stream anytime with the GOtv Stream App.

Plus, with the We Got You offer, available until 28th February 2026, subscribers automatically upgrade to the next package at no extra cost, giving you access to more channels this season.

Feature/OPED

Turning Stolen Hardware into a Data Dead-End

By Apu Pavithran

In Johannesburg, the “city of gold,” the most valuable resource being mined isn’t underground; it’s in the pockets of your employees.

With an average of 189 cellphones reported stolen daily in South Africa, Gauteng province has become the hub of a growing enterprise risk landscape.

For IT leaders across the continent, a “lost phone” is rarely a matter of a misplaced device. It is frequently the result of a coordinated “snatch and grab,” where the hardware is incidental, and corporate data is the true objective.

Industry reports show that 68% of company-owned device breaches stem from lost or stolen hardware. In this context, treating mobile security as a “nice-to-have” insurance policy is no longer an option. It must function as an operational control designed for inevitability.

In the City of Gold, Data Is the Real Prize

When a fintech agent’s device vanishes, the $300 handset cost is a rounding error. The real exposure lies in what that device represents: authorised access to enterprise systems, financial tools, customer data, and internal networks.

Attackers typically pursue one of two outcomes: a quick wipe for resale on the secondary market or, far more dangerously, a deep dive into corporate apps to extract liquid assets or sellable data.

Clearly, many organisations operate under the dangerous assumption that default manufacturer security is sufficient. In reality, a PIN or fingerprint is a flimsy barrier if a device is misconfigured or snatched while unlocked. Once an attacker gets in, they aren’t just holding a phone; they are holding the keys to copy data, reset passwords, or even access admin tools.

The risk intensifies when identity-verification systems are tied directly to the compromised device. Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), widely regarded as a gold standard, can become a vulnerability if the authentication factor and the primary access point reside on the same compromised device. In such cases, the attacker may not just have a phone; they now have a valid digital identity.

The exposure does not end at authentication. It expands with the structure of the modern workforce.

65% of African SMEs and startups now operate distributed teams. The Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) culture has left many IT departments blind to the health of their fleet, as personal devices may be outdated or jailbroken without any easy way to know.

Device theft is not new in Africa. High-profile incidents, including stolen government hardware, reinforce a simple truth: physical loss is inevitable. The real measure of resilience is whether that loss has any residual value. You may not stop the theft. But you can eliminate the reward.

Theft Is Inevitable, Exposure is Not

If theft cannot always be prevented, systems must be designed so that stolen devices yield nothing of consequence. This shift requires structured, automated controls designed to contain risk the moment loss occurs.

Develop an Incident Response Plan (IRP)

The moment a device is reported missing, predefined actions should trigger automatically: access revocation, session termination, credential reset and remote lock or wipe.

However, such technical playbooks are only as fast as the people who trigger them. Employees must be trained as the first line of defence —not just in the use of strong PINs and biometrics, but in the critical culture of immediate reporting. In high-risk environments, containment windows are measured in minutes, not hours.

Audit and Monitor the Fleet Regularly

Control begins with visibility. Without a continuous, comprehensive audit, IT teams are left responding to incidents after damage has occurred.

Opting for tools like Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) allows IT teams to spot subtle, suspicious activities or unusual access attempts that signal a compromised device.

Review Device Security Policies

Security controls must be enforced at the management layer, not left to user discretion. Encryption, patch updates and screen-lock policies should be mandatory across corporate devices.

In BYOD environments, ownership-aware policies are essential. Corporate data must remain governed by enterprise controls regardless of device ownership.

Decouple Identity from the Device

Legacy SMS-based authentication models introduce avoidable risk when the authentication channel resides on the compromised handset. Stronger identity models, including hardware tokens, reduce this dependency.

At the same time, native anti-theft features introduced by Apple and Google, such as behavioural theft detection and enforced security delays, add valuable defensive layers. These controls should be embedded into enterprise baselines rather than treated as optional enhancements.

When Stolen Hardware Becomes Worthless

With POPIA penalties now reaching up to R10 million or a decade of imprisonment for serious data loss offences, the Information Regulator has made one thing clear: liability is strict, and the financial fallout is absolute. Yet, a PwC survey reveals a staggering gap: only 28% of South African organisations are prioritising proactive security over reactive firefighting.

At the same time, the continent is battling a massive cybersecurity skills shortage. Enterprises simply do not have the boots on the ground to manually patch every vulnerability or chase every “lost” terminal. In this climate, the only viable path is to automate the defence of your data.

Modern mobile device management (MDM) platforms provide this automation layer.

In field operations, “where” is the first indicator of “what.” If a tablet assigned to a Cape Town district suddenly pings on a highway heading out of the city, you don’t need a notification an hour later—you need an immediate response. An effective MDM system offers geofencing capabilities, automatically triggering a remote lock when devices breach predefined zones.

On Supervised iOS and Android Enterprise devices, enforced Factory Reset Protection (FRP) ensures that even after a forced wipe, the device cannot be reactivated without organisational credentials, eliminating resale value.

For BYOD environments, we cannot ignore the fear that corporate oversight equates to a digital invasion of personal lives. However, containerization through managed Work Profiles creates a secure boundary between corporate and personal data. This enables selective wipe capabilities, removing enterprise assets without intruding on personal privacy.

When integrated with identity providers, device posture and user identity can be evaluated together through multi-condition compliance rules. Access can then be granted, restricted, or revoked based on real-time risk signals.

Platforms built around unified endpoint management and identity integration enable this model of control. At Hexnode, this convergence of device governance and identity enforcement forms the foundation of a proactive security mandate. It transforms mobile fleets from distributed risk points into centrally controlled assets.

In high-risk environments, security cannot be passive. The goal is not recovery. It is irrelevant, ensuring that once a device leaves authorised hands, it holds no data, no identity leverage, and no operational value.

Apu Pavithran is the CEO and founder of Hexnode

Feature/OPED

Daniel Koussou Highlights Self-Awareness as Key to Business Success

By Adedapo Adesanya

At a time when young entrepreneurs are reshaping global industries—including the traditionally capital-intensive oil and gas sector—Ambassador Daniel Koussou has emerged as a compelling example of how resilience, strategic foresight, and disciplined execution can transform modest beginnings into a thriving business conglomerate.

Koussou, who is the chairman of the Nigeria Chapter of the International Human Rights Observatory-Africa (IHRO-Africa), currently heads the Committee on Economic Diplomacy, Trade and Investment for the forum’s Nigeria chapter. He is one of the young entrepreneurs instilling a culture of nation-building and leadership dynamics that are key to the nation’s transformation in the new millennium.

The entrepreneurial landscape in Nigeria is rapidly evolving, with leaders like Koussou paving the way for innovation and growth, and changing the face of the global business climate. Being enthusiastic about entrepreneurship, Koussou notes that “the best thing that can happen to any entrepreneur is to start chasing their dreams as early as possible. One of the first things I realised in life is self-awareness. If you want to connect the dots, you must start early and know your purpose.”

Successful business people are passionate about their business and stubbornly driven to succeed. Koussou stresses the importance of persistence and resilience. He says he realised early that he had a ‘calling’ and pursued it with all his strength, “working long weekends and into the night, giving up all but necessary expenditures, and pressing on through severe setbacks.”

However, he clarifies that what accounted for an early success is not just tenacity but also the ability to adapt, to recognise and respond to rapidly changing markets and unexpected events.

Ambassador Koussou is the CEO of Dau-O GIK Oil and Gas Limited, an indigenous oil and natural gas company with a global outlook, delivering solutions that power industries, strengthen communities, and fuel progress. The firm’s operations span exploration, production, refining, and distribution.

Recognising the value of strategic alliances, Koussou partners with business like-minds, a move that significantly bolsters Dau-O GIK’s credibility and capacity in the oil industry. This partnership exemplifies the importance of building strong networks and collaborations.

The astute businessman, who was recently nominated by the African Union’s Agenda 2063 as AU Special Envoy on Oil and Gas (Continental), admonishes young entrepreneurs to be disciplined and firm in their decision-making, a quality he attributed to his success as a player in the oil and gas sector. By embracing opportunities, building strong partnerships, and maintaining a commitment to excellence, Koussou has not only achieved personal success but has also set a benchmark for future generations of African entrepreneurs.

His journey serves as a powerful reminder that with determination and vision, success is within reach.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn