Feature/OPED

X-Raying Oragwu’s Suggestions on Nigeria’s Science and Technology Dilemma

By Jerome-Mario Utomi

As a response to a recent intervention entitled Historical Perspectives on Nigeria’s Tertiary Education which among other things chronicled how Nigeria’s tertiary education originally got into trouble and with solutions on ways out of the debacle, I got several reactions/emails from esteemed readers.

Indeed, all contributions were well appreciated, but two qualified as outstanding.

The first queried; why can’t we as people forget the past and face the present/future? Why are you always in the habit of making reference to history?

In my response, I started by quoting EH Carr’s observation that history is an unending dialogue between the present and the past that assists the anxious inquirer in improving the present and the future based on a clearer understanding of the mistakes and achievements of the past. I submitted that it is only a society that has lost belief in its capacity to progress in the future will quickly cease to concern itself with the progress (or retrogress) in the past.

While the above query added a sidelight to the conversation, the second, though a mixture of private and public concerns was not only thought-provoking but strategic as it opened a vista that stemmed from new intervention.

It was an email from Professor Felix N.C Oragwu, Former Head of R&D Planning Division/Coordinator of Technological Services of the Technological Aspects of the Industrial War Machine that operated in the defunct State of Biafra, 1967-1970, Director in Charge of Industrial Research and Technology Innovation in NSTDA, Federal Government Cabinet Office, Lagos, 1977-1979.

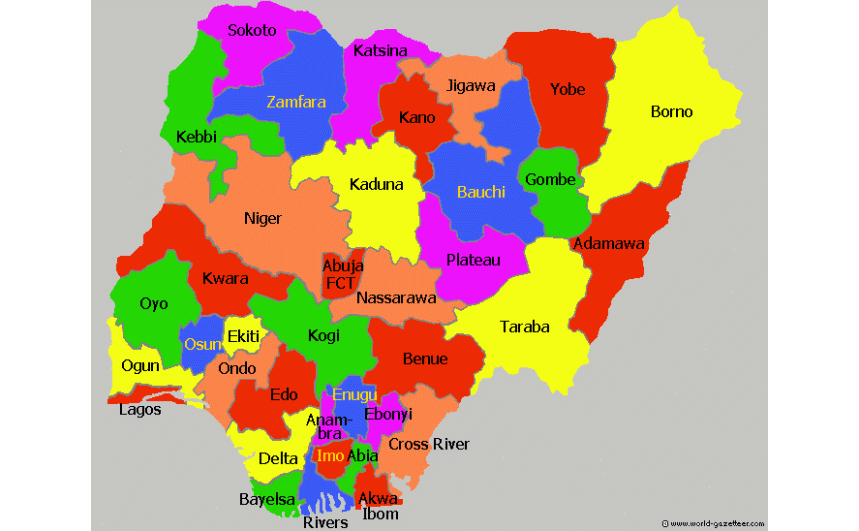

It reads; Hello,/Dear Jerome-Mario, Thank you and congratulations on your masterpiece on Historical Perspectives on Nigeria’s Tertiary Education now characterised by Certificate Acquisition without the relevant knowledge needed for its use/application in national development. This is well illustrated by the over 120 existing universities each with Faculties of Science, Engineering and Technology, and we cannot make a pin or produce/manufacture any technology/globally competitive industrial goods in our economy, both for domestic use and for export to the global market for foreign revenue. This is the consequence of our poverty, insecurity and criminality now ravaging Nigeria and nobody is asking questions. I hope Nigeria’s leadership, in particular those in politics and in government, will find time to read your wonderful writings and internalise their message. Congratulations again and my best wishes. Felix Oragwu, FSAN.

He did one more thing.

In his real zest to establish how Nigeria’s economy can move away from near-total dependence on imported technologies and imported industrial goods, to become a technology exporting nation, as the status of the economy of any nation is a function of the agricultural/mineral commodity endowment and the endogenous domestic capacity to produce modern technologies and industrial goods in the economy, he forwarded some materials to me out of which, his address titled: The Challenges of Science and Technology in Nigeria’s Economy: The Way Forward, delivered in March 2018 at Eagle Square, Abuja, the nation’s capital, during an event organised by the National Agency for Science and Engineering Infrastructure (NASENI), has emerged the focal point of this intervention.

At this point, critics may ask; what is spectacular about a keynote address? Haven’t we seen in the past more superlatively written, and creatively delivered addresses?

Indeed, these questions are all deserving but there are, however, many reasons that characterise the address as a vital road map. Aside from the public good consideration, others include the fact that it laid out how technological activities could be used as a key instrument for realizing Nigeria’s proposed Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP) points out how the nation has paid little attention to history, and lip service to science and technology, failed to learn from the highly successful technological innovations experience that took place in the defunct state of Biafra, 1967-1970: It more than anything else visibly spread out challenges posed by the inherited Lord Fredrick Lugard’s policy for S&T, Industrial/Economic Development in Nigeria.

Against this backdrop, as a demand by the intellectual property law which creates propriety rights over intangible assets, before further dissection of the address, this writer directs every credit to Oragwu as the greater paragraphs/plot of this writing is chiefly from the aforementioned keynote address.

However, with this alighted, it needs to be underlined also that sharing this priced information is predicated on informing those in the position of authority to such an existing road map which is part of my obligation as a citizen.

Beginning with the historical perspective of what set the groundwork for the present predicament science and technology suffers in the country, the keynote address pointed out how Lord Fredrick Lugard, first Nigeria’s Governor-General, 1914-1918, in his book titled The Dual Mandate of Europe in Tropical Africa, 4th Edition, London, 1929, enunciated the S&T policy for economic development in Nigeria on what he called a mutual agreement said to be existing between Britain and the colonised Nigeria.

In this so-called “agreement”, Nigeria is to export or supply Britain with primary agricultural commodities such as cocoa, palm oil/palm kernel, rubber, cotton, livestock hides and skins which Britain required for her once-famous textile industry and her leather and leather products industry, and to supply Britain with unprocessed natural minerals (solid, liquid and gaseous), which Nigeria has in abundance and which are of interest to Britain for the production and manufacture of technologies and industrial goods in the British economy.

Britain on her part is to “provide or export at costs to Nigeria, all the modern technologies and industrial goods that Nigeria needs to sustain her own economic growth and development”. Lord Lugard further stated in his book that that was the prime objective of the British colonization of Nigeria.

‘With this dual policy, a balance of trade between Nigeria and Britain was established. This policy means in effect that Nigeria should not develop any domestic capacity to produce and manufacture modern technologies and globally competitive industrial goods in Nigeria’s economy during the British colonial rule as that could undermine or compromise the mutual agreement.

This is when the rain of underdevelopment in science and technology began to beat Nigeria, apologies to Chinua Achebe, Nigeria’s internationally acknowledged novelist of Things Fall Apart.

This Lugard’s policy, he added, is recently alluded to in an article discussing Infrastructure and Africa’s Development and Prosperity: The Imperative of Public-Private Partnership (PPP), held in Abuja, Nigeria, on May 15-16, 2017, by one Engr. Chidi K. C. Ijuwa, of the Presidency, Abuja, Nigeria, made the following interesting observations, namely, (a) “the price of cocoa is declining in the world market but never the price of chocolates, (b) “the price of cotton may fall but never the price of clothes and garments, and (c) “the coffee farmers may face declining prices in the world market, but the coffee grinders and Starbucks will smile all the way to the banks”.

To make assurance doubly sure that the dual mandate was fully implemented, Britain, he noted, established only one University College, at Ibadan in 1948, coupled it with the Senate of the University of London. The University College was not allowed to offer courses in Engineering, Technology and professional courses but allowed full complement of courses in Latin and Greek (Classics), English History, Zoology, Botany, Geography, Organic Chemistry (initially no Physical Chemistry), Classical Physics, Agricultural Commodity Sciences, Mathematics (of 19th Century, G. Hardy of Cambridge University School of Mathematics who swore never to be alive to see his Mathematics applied), and Divinity respectively from 1948-1960.

Britain also made sure that during the British colonial rule, there were no Polytechnics, no Colleges of Technology and no Technical Colleges to train and develop skilled technical and professional manpower for technology and industrial goods production in Nigeria’s economy as that may breach the dual mandate.

There were also no Research and Development (R&D) institutions for technology production and industrial goods manufacture in Nigeria’s colonial economy. Has Nigeria’s leadership elite ever asked questions on these developments since 1960?

However, primary Agricultural Scientific Research Institutions, the address submitted were established for British West Africa including Nigeria such as West Africa Cocoa Research Institute with headquarters in Accra, Ghana, West Africa Oil Palm Research Institute with headquarters in Benin Nigeria, West Africa Trypanosomiasis Research Institute to address tsetse fly menace against cattle livestock, the source of raw hides and skins for leather and leather products industries in Britain,

Earlier in 1899, Britain established an Agricultural Experimental Scientific Research Station at Moor Station in Ibadan to experiment on primary cotton production in Southern Nigeria. Kano in Northern Nigeria produced abundant primary cotton but there were no roads and no railways then for use in transporting the raw cotton produce to Lagos seaport for onward shipment to Britain and Europe.

To be continued.

Utomi Jerome-Mario is the Programme Coordinator (Media and Policy), Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA), Lagos. He could be reached via je*********@***oo.com/08032725374.

Feature/OPED

How Christians Can Stay Connected to Their Faith During This Lenten Period

It’s that time of year again, when Christians come together in fasting and prayer. Whether observing the traditional Lent or entering a focused period of reflection, it’s a chance to connect more deeply with God, and for many, this season even sets the tone for the year ahead.

Of course, staying focused isn’t always easy. Life has a way of throwing distractions your way, a nosy neighbour, a bus driver who refuses to give you your change, or that colleague testing your patience. Keeping your peace takes intention, and turning off the noise and staying on course requires an act of devotion.

Fasting is meant to create a quiet space in your life, but if that space isn’t filled with something meaningful, old habits can creep back in. Sustaining that focus requires reinforcement beyond physical gatherings, and one way to do so is to tune in to faith-based programming to remain spiritually aligned throughout the period and beyond.

On GOtv, Christian channels such as Dove TV channel 113, Faith TV and Trace Gospel provide sermons, worship experiences and teachings that echo what is being practised in churches across the country.

From intentional conversations on Faith TV on GOtv channel 110 to true worship on Trace Gospel on channel 47, these channels provide nurturing content rooted in biblical teaching, worship, and life application. Viewers are met with inspiring sermons, reflections on scripture, and worship sessions that help form a rhythm of devotion. During fasting periods, this kind of consistent spiritual input becomes a source of encouragement, helping believers stay anchored in prayer and mindful of God’s presence throughout their daily routines.

To catch all these channels and more, simply subscribe, upgrade, or reconnect by downloading the MyGOtv App or dialling *288#. You can also stream anytime with the GOtv Stream App.

Plus, with the We Got You offer, available until 28th February 2026, subscribers automatically upgrade to the next package at no extra cost, giving you access to more channels this season.

Feature/OPED

Turning Stolen Hardware into a Data Dead-End

By Apu Pavithran

In Johannesburg, the “city of gold,” the most valuable resource being mined isn’t underground; it’s in the pockets of your employees.

With an average of 189 cellphones reported stolen daily in South Africa, Gauteng province has become the hub of a growing enterprise risk landscape.

For IT leaders across the continent, a “lost phone” is rarely a matter of a misplaced device. It is frequently the result of a coordinated “snatch and grab,” where the hardware is incidental, and corporate data is the true objective.

Industry reports show that 68% of company-owned device breaches stem from lost or stolen hardware. In this context, treating mobile security as a “nice-to-have” insurance policy is no longer an option. It must function as an operational control designed for inevitability.

In the City of Gold, Data Is the Real Prize

When a fintech agent’s device vanishes, the $300 handset cost is a rounding error. The real exposure lies in what that device represents: authorised access to enterprise systems, financial tools, customer data, and internal networks.

Attackers typically pursue one of two outcomes: a quick wipe for resale on the secondary market or, far more dangerously, a deep dive into corporate apps to extract liquid assets or sellable data.

Clearly, many organisations operate under the dangerous assumption that default manufacturer security is sufficient. In reality, a PIN or fingerprint is a flimsy barrier if a device is misconfigured or snatched while unlocked. Once an attacker gets in, they aren’t just holding a phone; they are holding the keys to copy data, reset passwords, or even access admin tools.

The risk intensifies when identity-verification systems are tied directly to the compromised device. Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), widely regarded as a gold standard, can become a vulnerability if the authentication factor and the primary access point reside on the same compromised device. In such cases, the attacker may not just have a phone; they now have a valid digital identity.

The exposure does not end at authentication. It expands with the structure of the modern workforce.

65% of African SMEs and startups now operate distributed teams. The Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) culture has left many IT departments blind to the health of their fleet, as personal devices may be outdated or jailbroken without any easy way to know.

Device theft is not new in Africa. High-profile incidents, including stolen government hardware, reinforce a simple truth: physical loss is inevitable. The real measure of resilience is whether that loss has any residual value. You may not stop the theft. But you can eliminate the reward.

Theft Is Inevitable, Exposure is Not

If theft cannot always be prevented, systems must be designed so that stolen devices yield nothing of consequence. This shift requires structured, automated controls designed to contain risk the moment loss occurs.

Develop an Incident Response Plan (IRP)

The moment a device is reported missing, predefined actions should trigger automatically: access revocation, session termination, credential reset and remote lock or wipe.

However, such technical playbooks are only as fast as the people who trigger them. Employees must be trained as the first line of defence —not just in the use of strong PINs and biometrics, but in the critical culture of immediate reporting. In high-risk environments, containment windows are measured in minutes, not hours.

Audit and Monitor the Fleet Regularly

Control begins with visibility. Without a continuous, comprehensive audit, IT teams are left responding to incidents after damage has occurred.

Opting for tools like Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) allows IT teams to spot subtle, suspicious activities or unusual access attempts that signal a compromised device.

Review Device Security Policies

Security controls must be enforced at the management layer, not left to user discretion. Encryption, patch updates and screen-lock policies should be mandatory across corporate devices.

In BYOD environments, ownership-aware policies are essential. Corporate data must remain governed by enterprise controls regardless of device ownership.

Decouple Identity from the Device

Legacy SMS-based authentication models introduce avoidable risk when the authentication channel resides on the compromised handset. Stronger identity models, including hardware tokens, reduce this dependency.

At the same time, native anti-theft features introduced by Apple and Google, such as behavioural theft detection and enforced security delays, add valuable defensive layers. These controls should be embedded into enterprise baselines rather than treated as optional enhancements.

When Stolen Hardware Becomes Worthless

With POPIA penalties now reaching up to R10 million or a decade of imprisonment for serious data loss offences, the Information Regulator has made one thing clear: liability is strict, and the financial fallout is absolute. Yet, a PwC survey reveals a staggering gap: only 28% of South African organisations are prioritising proactive security over reactive firefighting.

At the same time, the continent is battling a massive cybersecurity skills shortage. Enterprises simply do not have the boots on the ground to manually patch every vulnerability or chase every “lost” terminal. In this climate, the only viable path is to automate the defence of your data.

Modern mobile device management (MDM) platforms provide this automation layer.

In field operations, “where” is the first indicator of “what.” If a tablet assigned to a Cape Town district suddenly pings on a highway heading out of the city, you don’t need a notification an hour later—you need an immediate response. An effective MDM system offers geofencing capabilities, automatically triggering a remote lock when devices breach predefined zones.

On Supervised iOS and Android Enterprise devices, enforced Factory Reset Protection (FRP) ensures that even after a forced wipe, the device cannot be reactivated without organisational credentials, eliminating resale value.

For BYOD environments, we cannot ignore the fear that corporate oversight equates to a digital invasion of personal lives. However, containerization through managed Work Profiles creates a secure boundary between corporate and personal data. This enables selective wipe capabilities, removing enterprise assets without intruding on personal privacy.

When integrated with identity providers, device posture and user identity can be evaluated together through multi-condition compliance rules. Access can then be granted, restricted, or revoked based on real-time risk signals.

Platforms built around unified endpoint management and identity integration enable this model of control. At Hexnode, this convergence of device governance and identity enforcement forms the foundation of a proactive security mandate. It transforms mobile fleets from distributed risk points into centrally controlled assets.

In high-risk environments, security cannot be passive. The goal is not recovery. It is irrelevant, ensuring that once a device leaves authorised hands, it holds no data, no identity leverage, and no operational value.

Apu Pavithran is the CEO and founder of Hexnode

Feature/OPED

Daniel Koussou Highlights Self-Awareness as Key to Business Success

By Adedapo Adesanya

At a time when young entrepreneurs are reshaping global industries—including the traditionally capital-intensive oil and gas sector—Ambassador Daniel Koussou has emerged as a compelling example of how resilience, strategic foresight, and disciplined execution can transform modest beginnings into a thriving business conglomerate.

Koussou, who is the chairman of the Nigeria Chapter of the International Human Rights Observatory-Africa (IHRO-Africa), currently heads the Committee on Economic Diplomacy, Trade and Investment for the forum’s Nigeria chapter. He is one of the young entrepreneurs instilling a culture of nation-building and leadership dynamics that are key to the nation’s transformation in the new millennium.

The entrepreneurial landscape in Nigeria is rapidly evolving, with leaders like Koussou paving the way for innovation and growth, and changing the face of the global business climate. Being enthusiastic about entrepreneurship, Koussou notes that “the best thing that can happen to any entrepreneur is to start chasing their dreams as early as possible. One of the first things I realised in life is self-awareness. If you want to connect the dots, you must start early and know your purpose.”

Successful business people are passionate about their business and stubbornly driven to succeed. Koussou stresses the importance of persistence and resilience. He says he realised early that he had a ‘calling’ and pursued it with all his strength, “working long weekends and into the night, giving up all but necessary expenditures, and pressing on through severe setbacks.”

However, he clarifies that what accounted for an early success is not just tenacity but also the ability to adapt, to recognise and respond to rapidly changing markets and unexpected events.

Ambassador Koussou is the CEO of Dau-O GIK Oil and Gas Limited, an indigenous oil and natural gas company with a global outlook, delivering solutions that power industries, strengthen communities, and fuel progress. The firm’s operations span exploration, production, refining, and distribution.

Recognising the value of strategic alliances, Koussou partners with business like-minds, a move that significantly bolsters Dau-O GIK’s credibility and capacity in the oil industry. This partnership exemplifies the importance of building strong networks and collaborations.

The astute businessman, who was recently nominated by the African Union’s Agenda 2063 as AU Special Envoy on Oil and Gas (Continental), admonishes young entrepreneurs to be disciplined and firm in their decision-making, a quality he attributed to his success as a player in the oil and gas sector. By embracing opportunities, building strong partnerships, and maintaining a commitment to excellence, Koussou has not only achieved personal success but has also set a benchmark for future generations of African entrepreneurs.

His journey serves as a powerful reminder that with determination and vision, success is within reach.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn