Feature/OPED

Sacred Journeys, Earthly Burdens: The Cost of Nigeria’s Pilgrimage Economy

By Prince Charles Dickson PhD

The desert does not care for your prayers. It swallows them whole, along with your sweat, doubts, and wallet weight. Yet here we were—Nigerians in Jordan, then Israel, tracing paths carved by prophets and kings, stepping on stones smoothed by millennia of footsteps. From the Dead Sea’s buoyant bitterness to Bethlehem’s star-marked grottoes, the land thrums with sacred electricity. But as she walked, she couldn’t shake the question: What does this cost us? Not just in naira, but in soul.

You remember the chaos—Abuja’s airport buzzing with first-time pilgrims clutching rosaries and Qurans, tour guides shouting over the din, warnings about “japa temptations” mingling with sermons. For many, this was a once-in-a-lifetime escape: from potholed streets, blackouts, and the gnawing uncertainty of survival back home. Yet even here, in the shadow of Herod’s stones and Galilee’s shores, Nigeria followed us. The tour operators in Jordan haggled like Lagos market women; Israeli border guards scrutinized our green passports with weary suspicion. And beneath it all, the Gaza war hummed like a discordant hymn, a reminder that holiness and human conflict are ancient bedfellows.

Let’s talk numbers; if a single pilgrimage package costs roughly N3.5 to N5 million per person, multiply that by thousands of pilgrims annually, and Nigeria bleeds billions into foreign economies.

In Jordan, our guides grinned as they narrated Petra’s history, their pockets fattened by dollars. In Israel, the pilgrimage industry is a well-oiled machine: hotels near Nazareth charge premium rates, Dead Sea mud is packaged and sold as divine therapy, and even the Via Dolorosa has a gift shop. Meanwhile, back home, nurses strike over unpaid wages and students scratch equations into dust-choked chalkboards.

The Catholic Bishops’ recent call cuts like a knife: “Stop funding pilgrimages. Let faith pay its way.” Their logic is mercilessly practical: why should a nation drowning in debt—where 63% of citizens survive on less than $2 a day—subsidize spiritual tourism for a privileged few? The National Hajj Commission (NAHCON) and Christian Pilgrims’ Board, riddled with corruption scandals, stand as monuments to mismanagement.

Remember the 2017 scandal where officials embezzled ₦90 million meant for pilgrims’ visas? Or the 2022 Hajj airlift fiasco that stranded thousands? These boards, the bishops argue, “serve neither their adherents nor the nation.”

Yet, the allure persists. For many pilgrims, government sponsorship isn’t just a subsidy—it’s a lifeline. “I saved for ten years,” a retired teacher from Enugu told me, her eyes glistening at the Jordan River. “Without the board’s help, I’d never see Jerusalem.” Herein lies the paradox: pilgrimage is both a spiritual awakening and a symptom of systemic failure. When the state funds faith, it commodifies it—and when it withdraws, it risks severing the vulnerable from their solace.

Ah, the pilgrims themselves! Nigerians are nothing if not theatrical. There were the “Captains”—self-appointed prayer warriors who bossed others around like generals in God’s army. The Comedians, crack jokes at Caiaphas’ dungeon to ease the tension. The Holier-Than-Thous, who tsk-tsked at women’s uncovered hair while surreptitiously snapping selfies at Golgotha and the quiet ones, like the widow from Sokoto who touched the Western Wall and wept without sound.

But spirituality here is tangled with spectacle. At the Dead Sea, I watched a pastor bottle the salty water, declaring it “a weapon against household witches.” In Bethlehem, traders hawked olive-wood crosses next to “I Error! Filename not specified. Jesus” t-shirts. Is this awakening? Or is it the monetization of longing?

The bishops’ critique is not just fiscal—it’s theological. “True faith,” their statement insists, “is not measured in miles travelled but in mercy shown.” They urge a reckoning: if Nigeria redirected pilgrimage funds to healthcare, education, or infrastructure, could that itself be a sacred act? Imagine N30 billion—the approximate annual cost of state-sponsored pilgrimages—channeled into neonatal clinics or rural electrification. Would that not honor the “least of these” whom Christ called us to serve?

But the counterargument simmers: pilgrimages foster unity, they say. On that flight to Tel Aviv, I saw Muslims and Christians swap snacks and stories. A Hausa imam helped a Yoruba grandmother fasten her seatbelt. For a moment, Nigeria felt possible again. Yet this fragile camaraderie exists in a bubble—one paid for by a state that can’t fix its roads.

You asked me, “Can’t we have both—pilgrimages and progress?”* Perhaps. But not under this broken model. Here’s the radical alternative:

Decouple State and Sanctuary: Let religious groups self-organize pilgrimages, as the bishops propose. If a church or mosque can rally its flock to fund journeys, so be it—but without dipping into public coffers.

Audit the Sacred: Demand transparency from pilgrimage boards. Publish budgets, punish graft, and let pilgrims know exactly where their money goes.

Reinvest in the Here and Now: Redirect saved funds to tangible ministries—hospitals, schools, food banks—that embody “love thy neighbour” more vividly than any tour group.

On our last night in Jerusalem, I sat with a group under the stars. Nima from Plateau said quietly, “I came to feel closer to God. But I felt Him more when that waiter in Amman refilled my water…”. I urged her to tell the story—

It was the unlikeliest of sanctuaries—a crowded restaurant, humming with the chaos of clattering plates and overlapping voices. Amid the rush, a young waiter moved with a grace that transcended duty. His smile was not merely professional; it was an offering. In a world where transactions often eclipse connection, he chose to see me. I asked for three small things: hot water to refill my flask, a bowl of midnight-dark yogurt, and sugar to sweeten it—simple requests, yet specific, requiring attention in a sea of demands. He could have sighed, rolled his eyes, or deferred to the crowd. Instead, he leaned in.

His “of course” was a quiet rebellion against indifference.

The steaming flask returned, cradled like something sacred. The yogurt arrived, its darkness cradled in a bowl that gleamed like polished obsidian. The sugar, poured with care, became more than a condiment—it was a covenant.

At that moment, the noise faded. Here was a stranger who had every reason to rush, yet chose to pause. Here was proof that kindness is not a grand gesture reserved for saints, but a series of deliberate, ordinary acts: I will listen. I will try. You matter.

How much lighter the weight of our differences would be if we all carried this truth: that every interaction is a crossroads. We can choose to armour ourselves in a hurry, or we can meet one another as this young man did—with eyes that recognize a shared humanity. The systems we’ve built—borders, hierarchies, ideologies—are illusions compared to the raw, aching need we all harbor: to be treated gently, to be acknowledged.

As I stirred the sugar into the yogurt, dissolving bitterness into sweetness, I thought of all the ways we hunger. For warmth. For dignity. For the courage to ask for what we need, and the grace to honor those who ask. The world will not slow down. But in its frenzy, we can be oases for one another—pouring hot water into empty vessels, handing over sugar like a promise.

This is how we mend the fractures: not with grand declarations, but with the daily sacrament of paying attention. The waiter’s name is lost to me now, but his lesson lingers: in a universe that often feels cold and vast, we hold the power to make it intimate, one act of deliberate kindness at a time.

What if we all moved through life as he did—not merely serving, but seeing?

There it is—the heart of the matter. Spirituality isn’t stamped in a passport; it’s woven into daily acts of attention, kindness, and justice. Nigeria’s pilgrimage industry, for all its grandeur, risks reducing faith to a transactional spectacle. The bishops aren’t arguing against devotion—they’re pleading for a redefinition of what’s holy.

The desert still whispers. But maybe the miracle we need isn’t in Jordan’s rivers or Jerusalem’s tombs. Maybe it’s in the courage to stay home—to build a nation where the sacred isn’t a luxury, but a lived reality. May Nigeria win!

Feature/OPED

PETROAN, ‘Abiku Refineries’ and the Comfort of Collapse

A sector that keeps reviving what has repeatedly failed, while resisting what works, is not trapped by fate but comforted by collapse. PETROAN’s latest outburst exposes just how invested some interests remain in Nigeria’s ritualised dysfunction.

By Abiodun Alade

Nigeria’s oil and gas sector has endured many seasons of noise masquerading as advocacy. From time to time, pressure is applied not in pursuit of reform, but in defence of habits that have outlived their usefulness. The latest episode is revealing not because it is novel, but because it exposes, with unusual clarity, the discomfort of rent-seeking intermediaries when genuine change threatens familiar margins.

That discomfort has recently found expression in the agitation by the Petroleum Products Retail Outlets Owners Association of Nigeria over comments made by Bayo Ojulari, Group Chief Executive Officer of the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited. In demanding his resignation, PETROAN has inadvertently illuminated a deeper problem in Nigeria’s petroleum political economy: the resistance of entrenched intermediaries to reform that narrows the space for easy rent.

Ojulari’s offence was not misconduct. It was candour. He observed, correctly, that the Dangote Petroleum Refinery has provided breathing space at a time when government-owned refineries are shut, and that the NNPC should not rush back into the familiar ritual of pouring millions of dollars into turnaround maintenance for facilities that have become monuments to waste. This is not heresy; it is prudence.

For a quarter of a century, Nigeria has chased the mirage of refinery rehabilitation. Public records suggest that between $18 billion and $25 billion has been spent on turnaround maintenance and rehabilitation of the four state-owned refineries, with little to show for it. Like the abiku of Yoruba lore, these refineries are revived with ceremony, only to relapse almost immediately. Working today, dying tomorrow. To insist that this cycle must continue, regardless of evidence, is not patriotism. It is sabotage dressed as concern.

PETROAN’s reaction is therefore instructive. In a recent statement, its spokesman, Joseph Obele, described it as “most worrisome” that there was no urgency to restart the Port Harcourt Refinery because Dangote is meeting current fuel needs. The association went further, threatening to lobby civil society groups and pursue legal options to force the removal of the NNPC GCEO should the refinery not resume operations by March 1. This is not policy engagement. It is pressure politics.

Why would a body of retailers, whose business model depends largely on buying and reselling products refined elsewhere, be so hostile to domestic refining capacity? The answer lies in incentives. Domestic refineries compress margins. They reduce arbitrage. They expose inefficiencies that thrive in scarcity. For decades, fuel importation and the dysfunction it encouraged created space for unearned profits across the value chain. Local refining threatens that arrangement.

History offers a useful parallel. In Mancur Olson’s classic work The Logic of Collective Action, he explains how small, organised interest groups often prevail over the broader public interest because they are better motivated to defend narrow gains. PETROAN’s conduct fits this pattern. It speaks loudly, often, and with confidence, but for whom does it really speak?

It is also worth recalling PETROAN’s posture during earlier periods of distress in the sector. At moments when the national oil company was accumulating unsustainable obligations, remitting little or nothing to the Federation Account and absorbing enormous costs, commendations flowed freely. Laurels were dished out even as the system bled. That era ended with the Federal Government writing off substantial debts, including about $1.42 billion and N5.57 trillion after reconciliation. Nigerians paid the price for that indulgence.

During the years when Nigeria’s petroleum sector was driven to the brink, PETROAN looked the other way. The record is clear. The national oil company captured the entire value chain, seizing crude exports, monopolising refined product imports, and then forcing the Federal Government to borrow an estimated N500 billion monthly to sustain opaque subsidy claims. By controlling nearly 90 per cent of the roughly $3 billion in monthly crude proceeds routed through the Central Bank, and combining this with subsidy payments and other shocks, fiscal space collapsed, driving the government into massive Ways and Means financing.

At the same time, refinery rehabilitation became an industry without output. About $10 billion was spent over a decade on maintenance with nothing to show for it, not even a litre of petrol. A further $3 billion was later securitised against future crude sales for yet another failed repair cycle, a sum that could have delivered dozens of modular refineries. Even after the Petroleum Industry Act prioritised Domestic Crude Obligation, compliance remained elusive, while Nigeria continued to burn scarce foreign exchange importing substandard fuel into a system with no functional midstream. These were not marginal errors but a business model that plunged the country into crisis. Throughout it all, PETROAN’s voice was conspicuously muted, generous with praise where scrutiny was required.

This is why the current agitation rings hollow. Reform always unsettles those who prospered under disorder. President Bola Tinubu’s administration has signalled, through words and decisions, that it intends to break with the old script. Ojulari’s mandate at NNPC is clear: commercial discipline, efficiency and profitability. That mandate cannot be reconciled with endless rehabilitation theatre.

There is another uncomfortable question PETROAN has not answered. What value does its leadership bring to the petroleum sector beyond television appearances and press statements? Serious business leadership is measured in assets built, jobs created and value added. Publicly available information suggests that some of the companies associated with PETROAN’s leadership are modest in scale, with limited project footprints. Allegations and controversies reported in the public domain around some of these entities, whether in the power metering space or elsewhere, only reinforce the need for caution in elevating moral authority. Perhaps PETROAN’s members would do well to examine the records of those who speak in their name before an association meant to represent many is reduced to the private estate of a few and recast as an adversary of the public interest.

This is not to say that retailers have no role in policy debate. They do. But influence must be earned through insight, integrity and alignment with the national interest. Threats and ultimatums betray a lack of confidence in argument.

Nigeria stands at a fork in the road. One path leads back to ritualised waste, institutional failure and the comfort of familiar inefficiencies. The other leads to local capacity, competition and a petroleum industry that finally works for Nigerians. The Dangote Refinery is not a silver bullet, but it is a signal that the old excuses are losing credibility.

PETROAN’s nuisance value thrives only when reformers flinch. President Tinubu has shown little appetite for cheap blackmail. Ojulari enjoys his confidence for a reason. The task before NNPC is too important to be derailed by those nostalgic for a broken system. If PETROAN wishes to be relevant in this new era, it must evolve from noise to nuance. Otherwise, history will remember it not as a defender of consumers, but as a footnote in Nigeria’s long struggle to escape the tyranny of waste.

Abiodun, a communications specialist, writes from Lagos

Feature/OPED

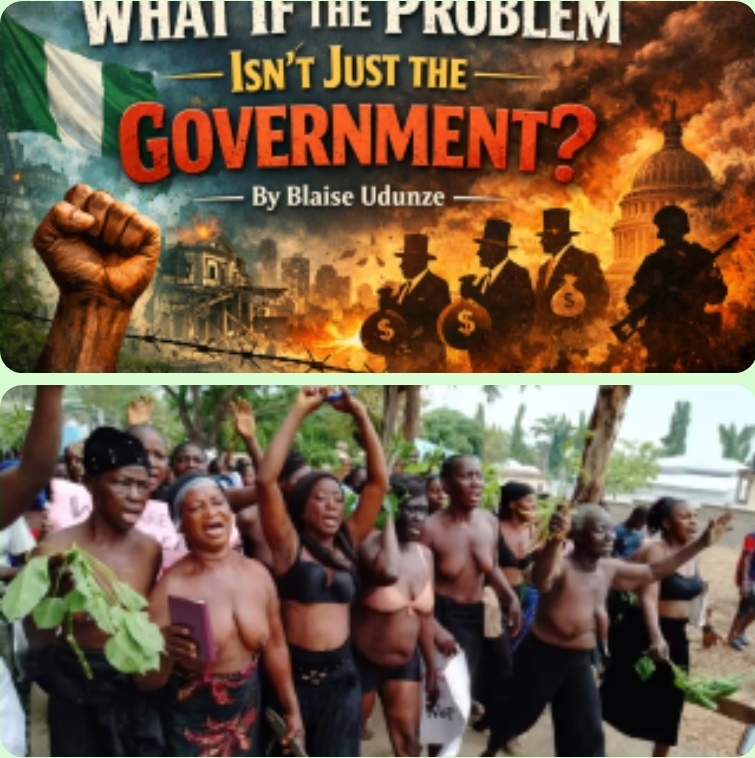

What If the Problem Isn’t Just the Government?

By Blaise Udunze

Recent reports in the media space highlighting threats of “naked protests” by market women across several states if the federal government fails to address the issue of hardship underscore the depth of hunger and poverty gripping the nation. No doubt, there is hardship in the country, of which Nigeria’s poverty crisis is often framed as the government’s failure, poor policies, weak institutions, corruption, and economic mismanagement.

From a balanced viewpoint, while these factors are undeniable, they do not tell the full story in its totality. The reality is that the majority of Nigerians, being the larger populace experiencing this challenge, will definitely oppose the ideology that poverty in Nigeria is not merely a policy problem; it is also a societal one. The underlying truth is that this is shaped by citizens’ behaviours, choices, cultural norms, and civic attitudes. This will remain a lived experience of the people until this dimension is confronted honestly; reforms will continue to yield limited results.

Nigeria’s economy has witnessed growth as inflation has decelerated, with headline inflation easing to 15.15percent and food inflation retreating to 10.84 per cent. The exchange rate was stabilising, and foreign reserves ($46.7 billion) had climbed to a seven-year peak. Despite the growth figures and ambitious government targets, millions of Nigerians remain trapped in poverty. More alarming is the recent estimates suggesting that an additional two million people could fall below the poverty line this year alone.

The intrigue is that the geographic distribution of these figures tells a deeper story, and this is more revealing than the numbers; however, there is an uneven geographical spread. Of concern here, which is troubling, is why states such as Yobe, Jigawa, Katsina, Kano, and Zamfara tend to experience or be deep in poverty when compared to other states like Lagos, Port Harcourt, Aba, Enugu, and Onitsha, which are projected to experience less poverty. This disparity raises a critical question, which calls for an urgent answer to why poverty outcomes differ so starkly within the same country, because no doubt, much of the explanation lies beyond government failures.

While governance challenges exist nationwide, the explanation extends beyond Abuja. Perhaps this is from deliberate ignorance of the people; the reality is that it lies in education, cultural practices, social norms, and individual responsibility play decisive roles in shaping economic outcomes.

One key alarming fact that has deeply entrenched poverty in many northern states, unlike other regions, is limited access to education, especially for girls, early marriage, polygamy, and large family sizes. There have been several factors that reinforce cycles of poverty by stretching limited household resources, reducing educational attainment, and limiting economic mobility, and this will continue to be a long-standing challenge or lived experience for the people if not addressed.

It is clearer that practical comparison illustrates this reality. Taking into consideration that a low-income worker in Yobe who marries four wives and raises over twenty children will inevitably struggle to provide adequate education, healthcare, and opportunities for his family, while in contrast, a similar worker in Aba is more likely to marry later, have fewer children, and invest in their education. Without much ado, over time, the children in the latter household acquire skills, productivity, and economic relevance because their parents chose to prioritise education for them, while the former remain trapped in subsistence and dependency. These differences are not subjective; they are structural and measurable.

Religion and culture further complicate the picture as record has it that Nigeria is one of the most religious countries in the world, yet religiosity often serves personal aspirations, prosperity, miracles, or divine favour rather than reinforcing civic responsibility and social ethics. Today in Nigeria, political leaders frequently reinforce this distortion and moral narrative. Only recently, it was announced that public officials in Abuja celebrate marrying off multiple children at once, some governors borrow billions to spend public funds on religious pilgrimages, while underfunding education, healthcare, and infrastructure, they send a clear message about priorities. In contrast, states that invest deliberately in education, such as Enugu with its smart school initiatives, demonstrate how leadership choices influence societal outcomes.

Still, the crisis of responsibility is not confined to any region. It is national, as proved during the discussions at Lagos State’s 12th Summit of the Association of Retired Heads of Service and Permanent Secretaries (ALARHOSPS), it was emphasised that societal progress depends not only on leadership but on citizenship behaviour. According to Professor Wusu Onipede, citizenship is defined by commitment to collective welfare, not mere residence.

The truth is not far-fetched, going by the saying that actions, positive or negative, directly impact society. What would have informed the common actions, such as stealing public assets, vandalising infrastructure, ignoring traffic laws, or tolerating corruption, all accumulate into widespread societal harm as seen in our everyday lives. Conversely, volunteering, mentorship, and community engagement generate resilience, opportunity, and shared prosperity. With close reading, one will notice that this dynamic was captured succinctly in Professor Oluwatomi Alade’s “Triangle for Change,” which pointed to the home, the school, and the community. Parents must brace up to understand that the primary responsibility is upon them to start prioritising education, teachers who impart both knowledge and character, and communities that uphold civic values create the foundation for sustainable development because the truth is that the change does not only rest on the government. In the same manner, it will be said that neglect in any of these spheres, whether through early marriage, disregard for schooling, or normalisation of polygamy, undermines national progress.

Religious institutions, as Professor Oguntola-Laguda argues, must also evolve, which means that beyond spiritual teachings, they should emphasise practical social ethics in the areas of responsibility, productivity, gender inclusion, and civic duty. In regions where harmful norms persist, faith leaders, traditional authorities, and elders possess the influence necessary to drive change, if they choose not to use it, otherwise the society will remain impoverished.

Globally, the link between social norms and poverty is well established, and norms that condone child marriage, gender exclusion, or unchecked family sizes perpetuate intergenerational deprivation. Over the period, in other countries, it is clear that economic interventions alone cannot dismantle these patterns because countries like India show that combining education incentives, political inclusion, and social protection can reduce poverty among marginalised groups. Initiatives such as Uganda’s SASA, which is a program that demonstrates that shifting attitudes toward gender and empowerment lead to improved economic outcomes. Nigeria’s poverty strategy must similarly integrate social transformation with economic reform.

None of this absolves government responsibility. Poorly sequenced reforms, rising taxes, insecurity, weak infrastructure, and inadequate social protection continue to deepen hardship. Senator David Mark of the African Democratic Congress has criticised what he terms “vicious policies” that worsen citizens’ vulnerability. Nigerians are acutely aware of these failures. What they demand is not statistics or political rhetoric, but practical policies that reduce hardship, enable productivity, and promote inclusion.

Even at this, Nigerians must take into cognisance that government action alone is insufficient. Poverty cannot be eradicated where large families are unsustainable, education is undervalued, and corruption is tolerated at the household and community levels. Individual responsibility remains the missing link. Citizens must be discreet in their timing for marriage until they can provide adequately, manage family sizes responsibly, educate all children, especially girls and reject the glorification of excess and impunity.

Insecurity further illustrates this shared responsibility. Though one will argue that the state bears the constitutional duty to protect lives and property, law and order, what about the dwellers? Communities must actively support security efforts through vigilance, information sharing, and conflict resolution. Silence in the face of crime and corruption enables disorder because independence loses meaning when citizens disengage from safeguarding their own communities.

Another critical aspect that is akin to insecurity is that economic development also falters when citizens undermine progress through dishonesty, rent-seeking, and apathy. What people fail to understand is that entrepreneurship, accountability, and cooperation are as vital as government-led job creation. The same thing can be said of cooperatives, vocational training, and local enterprise, which can deliver immediate relief and long-term sustainability. Wealthier Nigerians must focus on genuine social investment, creating opportunities, supporting education, and building institutions that outlast personal interest or individual generosity, rather than charity or wasteful spending or fueling crimes. Social responsibility must become a social norm.

One laughable misconception people harbour about independence, which must be clarified, is that it is not simply freedom from colonial rule; it is the presence of civic responsibility. It must be understood that poverty persists not only because of policy gaps but because of harmful norms, cultural practices, and neglected duties. Anyone can argue this, but the truth is that there will always be a replay of this menace kicked against because every child denied education, every early marriage, every act of corruption, reinforces the cycle.

Breaking this repeating problem, known as poverty, takes several coordinated strategies working together, not just one solution. There must be an understanding that the issues are complex and interconnected; they must be addressed from different angles at the same time. For these reasons, the government must provide stable policies, infrastructure, and social protection and the citizens, in like manner, must reform behaviours that perpetuate poverty. The same must be said of the families that must prioritise education, and also, the communities must reward civic engagement and innovation. Religious and cultural leaders must promote responsibility alongside faith because these are critical platforms that have the attention of the greater number of people. The policymakers at this juncture must ensure that policies not only deliver relief but also incentivise behaviours that support sustainable development.

Without too much argument, it is glaring that Nigeria’s potential is evident in states and communities that have embraced education, civic virtue, and social reform. Judging by the developments in different states, one will conclude that Lagos demonstrates how engagement and accountability improve outcomes, while Enugu shows that investing in children yields long-term dividends. Conversely, regions where harmful norms persist remain trapped, regardless of federal spending.

Without much ado, all Nigerian stakeholders must come to the terms that Nigeria’s poverty challenge cannot be reduced to government failure alone. It is a collective problem rooted in culture, norms, and personal choices because sustainable development demands both accountable leadership and responsible citizenship. The fact remains that poverty will remain an enduring shadow, irrespective of the repeated threats of “naked protests,” but until Nigerians fully embrace their role as architects, not just beneficiaries of national progress. True independence begins when citizens accept that the future of the nation rests as much in their daily choices as in public policy.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: [email protected]

Feature/OPED

AU Must Reform into an Institution Africa Needs

By Mike Omuodo

From an online post, a commentator asked an intriguing question: “If the African Union (AU) cannot create a single currency, a unified military, or a common passport, then what exactly is this union about?”.

The comment section went wild, with some commentators saying that AU no longer serves the interest of the African people, but rather the interests of the West and individual nations with greedy interests in Africa’s resources. Some even said jokingly that it should be renamed “Western Union”.

But seriously, how has a country like France managed to maintain an economic leverage over 14 African states through its CFA Franc system, yet the continent is unable to create its own single currency regime? Why does the continent seem to be comfortable with global powers establishing their military bases throughout its territories yet doesn’t seem interested in establishing its own unified military? Why does the idea of an open borders freak out our leaders, driving them to hide under sovereignty?

These questions interrogate AU’s relevance in the ensuing geopolitics. No doubt, the AU is still relevant as it still speaks on behalf of Africa on global platforms as a symbol of the continent’s unity. But the unease surrounding it is justified because symbolism is no longer enough.

In a continent grappling with persistent conflict, economic fragmentation, and democratic reversals, institutions are judged not by their presence, but by their impact.

From the chat, and several other discussion groups on social media, most Africans are unhappy with the performance of the African Union so far. To many, the organization is out of touch with reality and they are now calling for an immediate reset.

To them, AU is a club of cabals, whose main achievements have been safeguarding fellow felons.

One commentator said, “AU’s main job is to congratulate dictators who kill their citizens to retain power through rigged elections.” Another said, “AU is a bunch of atrophied rulers dancing on the graves of their citizens, looting resources from their people to stash in foreign countries.”

These views may sound harsh, but are a good measure of how people perceive the organization across the continent.

Blurring vision

The African Union, which was established in July 2002 to succeed the OAU, was born out of an ambitious vision of uniting the continent toward self-reliance by driving economic Integration, enhancing peace and security, prompting good governance and, representing the continent on the global stage – following the end of colonialism.

Over time, however, the gap between this vision and the reality on the ground has widened. AU appears helpless to address the growing conflicts across the continent – from unrelenting coups to shambolic elections to external aggression.

This chronic weakness has slowly eroded public confidence in the organization and as such, AU is being seen as a forum for speeches rather than solutions – just as one commentator puts it, “AU has turned into a farce talk shop that cannot back or bite.”

Call for a new body

The general feeling on the ground is that AU is stagnant and has nothing much to show for the 60+ years of its existence (from the times of OAU). It’s also viewed as toothless and subservient to the whims of its ‘masters’. Some commentators even called for its dissolution and the formation of a new body that would serve the interests of the continent and its people.

This sounds like a no-confidence vote. To regain favour and remain a force for continental good, AU must undertake critical reforms, enhance accountability, and show political courage as a matter of urgency. Without these, it may endure in form while fading in substance.

The question is not whether Africa needs the AU, but whether the AU is willing and ready to become the institution Africa needs – one that is bold enough to initiate a daring move towards a common market, a single currency, a unified military, and a common passport regime. It is possible!

Mr Omuodo is a pan-African Public Relations and Communications expert based in Nairobi, Kenya. He can be reached on [email protected]

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism9 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn