Feature/OPED

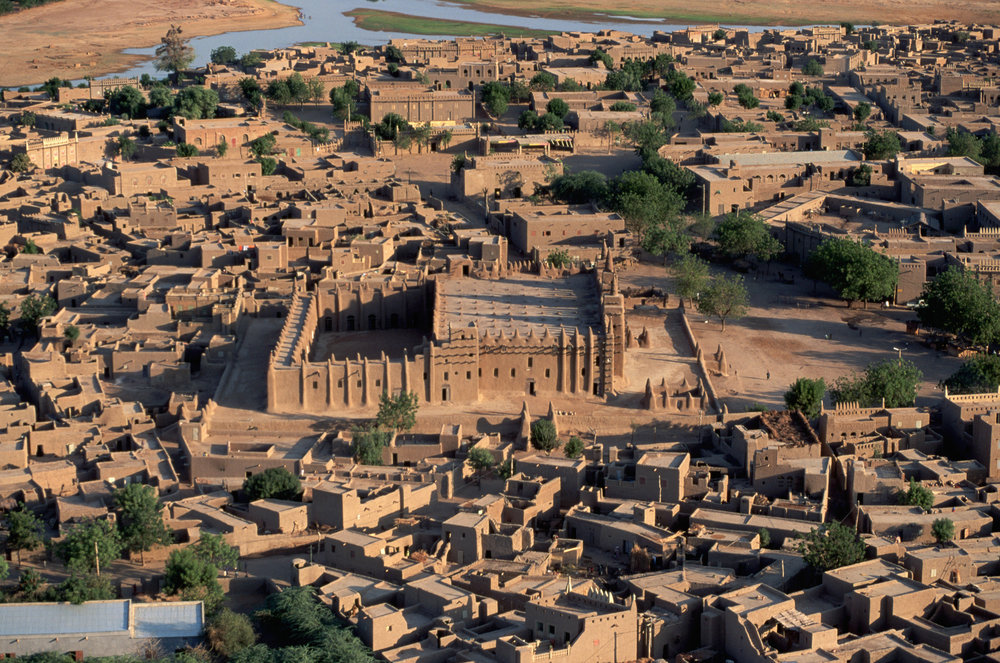

Ancient African Kingdoms, Innovation and Underdevelopment

By Nneka Okumazie

Why aren’t there an abundance of stories of conqueror kingdoms in Ancient Africa, say a major kingdom in East Africa, conquering territories up to Central and West Africa, or say a powerful kingdom in Southern Africa in alliance with one in West Africa, to fight back against the East African power?

It is known that there were wars around kingdoms in Africa long before colonization, but what kinds of wars, and to what ambitious extent?

Across the world, a small community may have favourable accidents at some era, causing them to have certain advantages, where others need them or that give them the leeway for risks, without instant failure.

This or new destinations drove many to war, sometimes learning, coming back, or triumphed across history. Assuming for ancient Africa, survival was war – total war, things would have been different.

There are at least some powerful ancient African kingdoms, they would have vanquished neighbouring uprising, but seemed they stuck to their power, or peace risking nothing more or going further – land or sea. This lack of war may also in part be responsible for Africa’s current underdevelopment.

Major wars – for all kinds of reasons, to conquer, expand, for resources, etc. would have given Africa some important qualities, risk, courage, and unity – in determination for purposes likely to fail, but important enough to try.

Talented people would have provided strategy, built tools, advantages and paths would have been sought, alternatives to winning may be planned, but each generation would have evolved with natural and cultural prowess that would have made development far easier.

However, the lack of development from the whole – points to an absence of internal structure that would have fostered it, with benefit for all, regardless of emerging struggles.

Slavery trade would have been less successful – than what happened, or African could have bargained better – in bringing those who left-back, before new ones went, or in ensuring industrial transfer – with stuff made in Africa, or growth sought in some of the kingdoms for emerging products.

But it seemed the war Africa got to fight was the luxury war – or say luxury sum game. The ancient African chiefs or rulers held power, got some form of irregular taxes, or land, had large families and got some of the best tools available for whatever they wanted, and left others so long no encroachment.

When the colonizers arrived, though violently in many cases, they eventually paid – in different ways for slaves and other access optimized to benefit the rulers, luxury, or keeping position was the show/goal.

It continues in many contemporary African societies, where the war is for luxury via position, politics, corporate, academic, critics, entertainment, religion, etc. where the intention is for the comfort of self, cronies or loved ones, but society can rot – no risk for it, no courage for growth, not unity for all.

[2 Samuel 23:12, But he stood in the midst of the ground, and defended it, and slew the Philistines: and the LORD wrought a great victory.]

Feature/OPED

How to Nurture Your Faith During Ramadan

Many Muslims grow up learning how to balance life carefully. Faith, work, and responsibility all sit on the same scale, and during Ramadan, that balance becomes even more delicate. Days start earlier than usual, nights stretch longer, and energy is spent with intention.

Over time, this rhythm shapes more than schedules; it quietly shapes how Ramadan is experienced.

Between getting ready for work, navigating long days, preparing meals for iftar, observing prayers, and trying to rest, moments for reflection are often pushed to the side. When there’s finally time to pause, many people assume meaningful Islamic content requires complete silence, full attention, and emotional space, things that can feel scarce during the month.

They scroll past channels they believe may be too formal, or not suited to their everyday routine. They stick to what feels familiar, even if it doesn’t quite align with the spirit of the season and without realising it, they limit themselves.

What many don’t know is that content designed for moments like these already exists on GOtv. The Islam Channel offers programming that understands Ramadan as it is truly lived.

On the Islam Channel, viewers can find thoughtful discussions that explore faith in a way that feels relevant to modern life, educational programmes that break down Islamic teachings clearly and calmly, and inspiring shows that encourage reflection without feeling overwhelming. There are conversations that can play softly in the background while you’re cooking, reminders you can catch while getting dressed for work, and programmes that help you unwind gently after a long day of fasting.

What sets the channel apart is how it personalises Islamic themes, making them accessible not just during prayer time, but throughout the day. Its content is created to inform, reflect, and inspire, whether you’re actively watching or simply listening as life continues around you. And while it speaks directly to Muslim audiences, it also remains open and welcoming to non-Muslims interested in understanding Islamic values, culture, and everyday perspectives.

During Ramadan, television often becomes part of the atmosphere rather than the focus. And having access to content that aligns with the season can quietly enrich those in-between moments, the ones that often matter most.

This Ramadan, the Islam Channel is available on GOtv Ch 111, ready to meet you wherever you are in your day.

And here’s the exciting part: with GOtv’s We Got You offer, you can enjoy your current package and get access to the next package at no extra cost. There’s never been a better time to hop on and get more shows, more suspense, and more entertainment, all for the same price!

To upgrade, subscribe, or reconnect, download the MyGOtv App or dial *288#. For watching on the go, download the GOtv Stream App and enjoy your favourites anytime, anywhere.

Feature/OPED

Is Nigeria Borrowing to Survive or to Build?

By Blaise Udunze

Nigeria is no longer flirting with deficit financing. As a country, it is living with it, not occasionally but structurally, routinely, almost comfortably. It became evident when the National Assembly rose to defend the proposed N25.91 trillion deficit in the N58.47 trillion 2026 budget that it did more than justify another year of borrowing. It normalised it. Again, the message had been clearly defined that deficit financing is no longer a temporary response to shocks; it is now a structural feature of Nigeria’s fiscal architecture.

This was confirmed by the Senate, which, led by Senator Solomon Adeola, who defended continued borrowing as inevitable. In agreement with his defence, Senator Olamilekan Adeola argued that borrowing is inevitable in the face of unpredictable revenue and vast development needs. He is not wrong. No modern economy runs without deficits. The United States borrows. European economies borrow. Even fast-growing Asian Economies have used deficits strategically.

The real issue, as Adeola himself admitted, is how Nigeria borrows and what it borrows for.

That is where the debate becomes uncomfortable. Looking at it objectively, in a plain calculation, almost half of what the federal government hopes to earn will go straight to creditors. The chronic issue is that Nigeria’s projected revenue for 2026 stands at N33.19 trillion, while expenditure is estimated at N58.47 trillion, leaving a yawning gap of over N25 trillion. Debt service alone is expected to gulp nearly N15.9 trillion. In other words, before roads are built, before hospitals are equipped, before schools are renovated, almost half of the projected revenue is already committed to servicing yesterday’s loans.

Of paramount concern is that the action being discussed does not serve as a policy that supports the economy; it is a counter-cyclical stimulus during downtime to stabilise growth. It is a structural dependence. This is to say that at the core of Nigeria’s deficit dilemma lies revenue weakness. Despite the much-touted diversification of the economy, the country remains heavily dependent on crude oil for foreign exchange and for a significant share of public revenue. The fearful part is that when oil prices fall, when production drops due to theft or quotas, or when global demand weakens, government revenue collapses. Expenditure, however, does not fall with oil prices. Salaries must be paid. Pensions must be honoured. Political offices must function. Debt must be serviced. Borrowing fills the gap.

Beyond oil, the non-oil tax base remains shallow. Nigeria’s tax-to-GDP ratio lags far behind peer economies. One of the challenges is that, as a vast informal sector, weak tax administration, compliance gaps, waivers, and leakages mean that even in years of non-oil growth, revenue does not rise proportionately. One truth the country must yield to is the advice of Minister of Finance, Wale Edun, who rightly warned that Nigeria must reduce its dependence on debt and build a stronger domestic revenue base. This stems from his understanding that in a world of high global interest rates and retreating multilateral support, borrowing is becoming more expensive and less forgiving. Yet the borrowing continues.

One troubling fact from the disclosure of the Debt Management Office (DMO) is not that Nigeria’s public debt stood at over N152 trillion by mid-2025, but it is projected to climb further. What makes this figure more of a trouble is not just its size, but its purpose. Historically, Nigeria once escaped the weight of unsustainable debt through the Paris Club exit negotiated under President Olusegun Obasanjo. Two decades later, the country finds itself in a far more complex web of domestic and external obligations. The question is simple in the sense of what has the borrowing built?

If deficits finance productive infrastructure that expands the economy’s capacity, power plants that reduce production costs, rail lines that ease logistics, and digital infrastructure that boosts exports, then borrowing can be justified. Future growth will expand the tax base and service the debt. Hence, it will be agreed that deficits, in that scenario, become bridges to prosperity.

But if deficits finance recurrent expenditure, salaries, overheads, fuel subsidies, political patronage, interest payments, then borrowing becomes a treadmill. The country runs harder each year, yet moves nowhere.

Nigeria’s fiscal pattern increasingly resembles the latter. Recurrent expenditure consumes a significant portion of revenue. In some years, debt service has exceeded the federal government’s retained revenue. This forces further borrowing simply to keep government machinery running. Borrowing to service old debt is the classic signature of a fiscal trap.

Meanwhile, the crowding-out effect is becoming pronounced. With the government aggressively issuing domestic debt instruments, over 70 per cent of risk assets in the financial system are reportedly tied to government securities. Banks prefer lending to the government at high yields rather than financing private businesses. Lending rates, influenced by a high monetary policy rate, hover between 35 and 40 per cent. For manufacturers, farmers, and tech entrepreneurs, such rates are prohibitive.

In effect, the state is absorbing liquidity that could otherwise power private-sector growth. The engine of sustainable revenue, the productive economy, is being starved.

Supporters of the current approach argue that deficits are necessary to close Nigeria’s massive infrastructure gap. Contrary to their argument, the roads are dilapidated. Power supply remains unreliable. Security spending has ballooned in response to persistent threats. With a fast-growing population, social spending pressures are immense. In such a context, refusing to borrow would mean freezing development.

That argument carries weight. Nigeria cannot austerity its way to prosperity. While slashing expenditure indiscriminately could worsen unemployment and deepen poverty.

However, borrowing without institutional reform is a lot more dangerous. Economist Adi Bongo has warned that asset sales, privatisations, and new borrowing will fail without strong oversight and accountability. Nigeria’s history of public-private partnerships and sectoral reforms, particularly in the power sector, offers cautionary tales. Assets sold to politically connected entities without capacity did not deliver efficiency gains. Institutions were created but not empowered. Data was published but not interrogated. Borrowing into weak institutions is like pouring water into a leaking basket.

There is also the issue of political budgeting. Election cycles often bring expanded spending and proliferating projects. Revenue does not necessarily rise in tandem. Structural deficits become politically convenient. Once normalised, they are difficult to reverse.

The Senate President, Godswill Akpabio, who recently framed the 2026 budget as a “moral document,” said it must therefore be judged not by its size, but by its outcomes. The question that should follow such a comment is, will the N26 trillion capital allocation translate into completed roads, functional health centres, and reliable electricity? Or will delayed releases, procurement bottlenecks, and weak oversight roll projects into yet another fiscal year?

Nigeria’s history of overlapping budgets and low capital implementation rates raises legitimate scepticism. Economists have cautioned that attempting to execute multiple large budgets concurrently strains administrative capacity and encourages rushed, low-value spending. When execution falters, the borrowed funds do not generate returns. Yet the interest meter keeps running.

Subsidy reform illustrates both the promise and the risk. The removal of fuel subsidy under President Bola Tinubu was described as a turning point, which was commended by an international organisation. In theory, eliminating subsidies should free fiscal space for productive investment like infrastructure, health, or education, as expected. But transparency in how those savings are redeployed remains crucial, especially in how the subsidy removal is being used. The truth remains that trust erodes if citizens do not see tangible improvements in infrastructure and services to showcase how the money realised from subsidies is being expended. Compliance weakens because once trust and fairness decline, people will easily default or be less willing to obey rules (like paying taxes or following regulations). Revenue mobilisation becomes harder. Trust is the invisible currency of fiscal reform.

Exchange rate pressures add another layer of complexity. When the naira weakens, external debt servicing costs rise in local currency terms; import-related spending increases. Even if reserves appear strong, they are not freely spendable funds; they are buffers against external shocks. Mistaking reserves for budgetary liquidity is a dangerous illusion.

The global context is also less forgiving. Developing countries now pay far more in debt service than they receive in aid. Capital flows are volatile. In such an environment, fiscal discipline is not optional; it is survival.

So, are Nigeria’s deficits building future revenue capacity or merely financing present consumption?

The evidence is mixed, but the tilt is worrying. There are genuine reform efforts underway, such as tax administration overhaul, digitised revenue monitoring, electricity sector reforms, and efforts to attract capital importation. There are signs of macroeconomic stabilisation that are moderating inflation, improving reserves, and modest GDP growth. These are not trivial.

Yet the scale and persistence of deficits, the heavy burden of debt service, the crowding-out of private credit, and the lack of transparency around execution suggest that borrowing is increasingly funding continuity rather than transformation or driving meaningful structural change.

Deficit financing becomes a growth strategy only when three conditions are met, such as when borrowed funds are channeled into productivity-enhancing investments (such as infrastructure, energy, manufacturing, education, and these things must expand the economy’s capacity to produce); institutions ensure transparency and value for money; and economic growth outpaces debt accumulation, so the country can comfortably service and repay what it has borrowed. When those conditions weaken, deficits mutate into a fiscal trap.

Nigeria stands at that junction. The Senate is right that borrowing in itself is not evil. But normalising structural deficits without tightening or simultaneously enforcing expenditure discipline, expanding revenue beyond oil, strengthening institutions, and reducing the cost of governance, then the country is taking a significant risk.

A nation can borrow to build bridges. Or it can borrow to pay salaries. The former compounds growth. The latter compounds debt.

If Nigeria’s deficits do not translate into visible infrastructure, expanded industrial capacity, thriving private enterprise, and rising tax revenues, history will record this era not as bold reform, but as deferred reckoning.

Deficits are not destiny. But when they become routine, they stop being temporary tools, unexamined, and politically convenient; they shape the destinies of Nigerians. From today, as a sovereign nation, Nigeria must decide whether it is borrowing to survive the present or to secure the future. The choice Nigeria makes about how it uses deficit financing will determine whether it becomes a growth ladder or locks it into a worsening cycle of debt that becomes harder and more expensive to escape over time, while the cost of escaping grows each year.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: [email protected]

Feature/OPED

Billions in Nigeria’s Reserves, But Where is the Growth?

By Blaise Udunze

The moment the Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Olayemi Cardoso, recently announced that Nigeria’s foreign reserves had inched to $49 billion as of February 5, 2026, the news was received with understandable enthusiasm.

He described the development as “a very important statistic” when speaking at the 2nd National Economic Council (NEC) Conference in Abuja, while noting a 4.93 per cent increase and emphasising that Nigeria had moved from being a net seller to a net buyer of foreign exchange. He cited improved remittance inflows, a narrowing gap between official and parallel market exchange rates, and greater confidence in the naira as evidence that reforms were working.

On the surface, the numbers are reassuring. The premium between official and parallel market rates has reportedly fallen to under 2 per cent. Remittances have improved following deliberate engagement with the diaspora. Nigerians can increasingly rely on naira cards for international transactions. It can be said that investors are earning positive real returns, banks are recapitalising, equity markets are recovering, and macroeconomic indicators such as GDP growth of 3.98 per cent, a current account surplus of $3.42 billion in the third quarter of 2025, and a reported moderation in inflation to 15.15 per cent are presented as signs of stabilisation.

So far, beyond the celebratory headlines lies a deeper and more consequential question, in the form of, what does the fixation on foreign reserves really tell us about the underlying strength of the Nigerian economy?

History and economic logic suggest that when a central bank repeatedly elevates foreign reserves as a central achievement, it often signals that the true engines of growth are either weak or underdeveloped. Strong reserves are not built through declarations, press conferences, or defensive monetary manoeuvres. They are built through systems that generate value, exports, productivity, and trust. Countries with durable reserve positions did not chase reserves; they built economies that produced them naturally.

This distinction matters greatly for Nigeria.

Foreign reserves are important, but they are not a development strategy. They are a buffer, not a foundation. They are an outcome of economic vitality, not a substitute for it. When reserves become the centrepiece of economic storytelling, there is a risk that policymakers mistake statistical comfort for structural strength.

Even Nigeria’s celebrated $49 billion reserve figure requires closer scrutiny, which appears to be more of sexing up the figures. Gross reserves make headlines, but net usable reserves are what protect a currency in moments of stress. A significant portion of reported reserves is often tied up in swaps, forward commitments, and external obligations. When these are stripped out, the net buffer available to defend the naira is far smaller than the headline figure suggests. The gap between gross and net reserves is too large to justify unqualified confidence about currency stability, especially in an economy that remains import-dependent and structurally fragile.

The danger of over-fixating on reserves is not unique to Nigeria, but it is particularly acute here because of the economy’s narrow production base, which subliminally calls for sexing up the figures. Despite decision-makers prematurely applauding the reserves’ growth, the apex bank must rethink its approach. The reserves are not generated through production-based or stronger export means but rather largely from borrowing (sales of Eurobonds) or through government loans, which come in as dollars to the CBN that temporarily boost dollar inflows. This points to the fact that Nigeria still exports little beyond crude oil, imports most manufactured goods, and relies heavily on volatile capital inflows. In such a context, reserves require constant defence rather than organic replenishment. Tight monetary policy, FX restrictions, and moral persuasion may buy time, but they do not solve the underlying problem of insufficient foreign exchange generation.

By contrast, countries with strong reserve positions followed a very different path. Unlike Nigeria, countries like Saudi Arabia, with foreign reserves of about $410 billion, paired subsidy reforms with visible reinvestment in infrastructure, social welfare, and alternative energy systems. Indonesia, with reserves of roughly $153 billion, combined fiscal reforms with expanded social assistance and a shift toward targeted household support, ensuring that reform pain was offset by tangible benefits. Reserves are mainly meant to grow from productive economic activities like Singapore, whose reserves stood at approximately $397 billion at the end of 2025, as it built its position through decades of disciplined industrial policy, export competitiveness, domestic savings, and institutional credibility. In all these cases, reserves were not the objective; they were the by-product of deliberate economic architecture.

In most successful developmental states, public expenditure plays a catalytic role in growth. Unlike Nigeria’s, most countries’ expenditures It crowds in private investment, expand infrastructure, lower transaction costs, and build productive capacity. Over time, this deepens domestic capital formation, drives industrial productivity, supports export diversification, and strengthens external balances. Nigeria’s recent experience, however, appears to diverge from this model.

Rather than deploying fiscal policy aggressively to stimulate productive capacity, government financing has increasingly leaned on the domestic capital market. While this approach has attracted foreign capital inflows, much of this capital has been short-term portfolio investment into treasury bills, government bonds, and money market instruments. A fact that is well established is that these inflows can temporarily stabilise liquidity and support the exchange rate, but their multiplier effects on the real economy are minimal. In the absence of strong productive investment for a country like Nigeria, the giant of Africa, this pattern resembles constructing a skyscraper on weak foundations, which is impressive in appearance, but structurally fragile.

This fragility is evident in the broader economy. Especially this kind of growth is associated with Nigeria in 2025, which portrays a country that is increasingly survival-led rather than productivity-driven. The underlying challenge today is that households, small businesses and even industrial firms are left with no option but to adapt to rising costs and shrinking real incomes by expanding low-productivity activities. Industrial depth remains shallow. Domestic capital accumulation is weak. Export capability outside oil is limited. Labour productivity continues to lag. These are not the conditions under which reserves become self-sustaining.

This is why the central bank’s strategic focus must extend far beyond reserve accumulation. If the CBN genuinely seeks to grow the economy and build reserves sustainably, it must prioritise the mechanisms that generate foreign exchange organically. The most important of these is productive credit expansion. Central banks around the world are expected to shape economies not only through interest rates but through the direction of credit. Prolonged monetary tightness may suppress inflation at the margins, but it also suppresses investment, output, and employment, as is the case in Nigeria. Contrary to Nigeria’s lived experience, countries that successfully built reserves deliberately channelled affordable, long-term credit to manufacturing, agro-processing, and export-oriented sectors, but the same cannot be said of Nigeria. Nigeria cannot tighten its way into prosperity.

Closely linked to this is the need for a serious export-led industrial strategy. Nigeria’s trade challenge is often framed as an import problem, but it is fundamentally an export deficiency. Banning imports or rationing foreign exchange does not create competitiveness. Export growth does. Sustainable reserves come from selling more to the world than one buys, particularly in manufactured goods and tradable services. Oil exports may still matter, but they are volatile and finite. Value-added exports are repeatable, scalable, and employment-intensive.

Exchange rate stability, too, must be approached through supply rather than fear. Currency pressure reflects insufficient FX supply more than excessive demand. Strengthening real economic fundamentals, which calls for expanding non-oil exports, formalising remittance channels, and attracting long-term productive capital, will do more to stabilise the naira than administrative controls mixed with sexing up figures. Predictability matters, and for this reason, investors may tolerate risk, but they may be forced to withdraw when policies are inconsistent.

Infrastructure financing is another critical missing link. No economy exports competitively without reliable power, efficient transport, and functional logistics. While infrastructure is often treated as a purely fiscal responsibility, central banks in many emerging economies have played catalytic roles in financing industrial infrastructure. Supporting industrial parks, logistics hubs, processing zones, and energy projects would address one of the root causes of Nigeria’s weak export performance and fragile reserves.

Equally important is the mobilisation of domestic savings. Strong reserves are easier to build when a country funds its development internally. One of its domestic savings that has been lying fallow is that Nigeria’s pension and insurance funds remain under-deployed in productive sectors. For a country that is truly angling for growth and with the right regulatory frameworks, these long-term pools of capital can support infrastructure, manufacturing, and export industries, reducing dependence on volatile foreign inflows.

Inflation control must also be re-examined. This is one grey area with Nigeria’s system as its inflation is largely cost-driven, fueled by energy costs, logistics bottlenecks, FX shortages and insecurity. It must be understood that addressing it solely through interest rate hikes risks shrinking output in terms of economic production and growth while prices remain elevated, as is the case today. The policy-makers in Nigeria must understand that supply-side interventions that reduce production costs and stabilise input availability are more likely to deliver durable price stability and stronger reserves than monetary tightening, especially in the case of raising interest rates alone.

The CBN has projected that GDP growth could reach 4.49 per cent, inflation could moderate to 12.9 per cent, and reserves could exceed $50 billion. These projections are presented as evidence of consolidation. Yet many economists caution that macroeconomic stability, while necessary, is not synonymous with sustainable growth. Even if the provided official statistics may suggest that the economy is improving, the reality is that the majority of the populace are not experiencing the benefits, as is the case in Nigeria, where the unemployment rate is high, wages aren’t keeping up with costs, and many households are barely making ends meet.

To further drive the point, Gbenga Olawepo-Hashim has argued that the true measure of economic performance is not headline figures but the living conditions of citizens. This is to say that economic growth is meaningless if it doesn’t create jobs, purchasing power, and opportunity, cannot sustain political or social stability, nor can foreign reserves grow sustainably.

Going forward, it is advisable that the foreign reserves, therefore, should be read for what they are, as a reflection of deeper economic health. When production expands, exports diversify, infrastructure improves, capital deepens, and trust is restored, reserves grow quietly and sustainably. When these foundations are weak, reserves require constant defence and loud celebration.

Today, Nigeria is at a critical point where it must make a major decision, either the choice is between managing reserves endlessly or building an economy that earns them effortlessly. The former offers headlines and is unsustainable. The latter offers prosperity, and it is sustainable in the long term.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: [email protected]

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn