Feature/OPED

Balancing Business Success and Family Succession: Navigating ‘Deemed Offer’ Provisions in Startup Shareholder Agreements

It’s all too easy to think of startup founders as young, vigorous and touched with immortality. But the sector is full of stories of founders dying before their time. Such deaths are always tragic but can be even more so when there isn’t a clear plan in place. Without that plan, conflicts can quickly arise between the family of the deceased, investors, business partners, and other interested parties.

Often, the source of this conflict is the founder being subject to a “deemed offer” or “deemed sale” clause. This clause leads to an automatic forced sale of the deceased’s shares. When a deemed offer is in place, the deceased’s family can lose access to that person’s stake in the business, even if it’s earmarked for them in the will.

Knowing that how can founders safeguard the interests of their businesses and investors while protecting their family legacy? The answer relies on mastering the detail and being diligent in execution.

Understanding deemed offers

A deemed offer provision stipulates that under specific predefined circumstances — generally described as ‘trigger events’ — a shareholder is ‘deemed’ to have offered their shares to the company and/or the remaining shareholders for purchase. In agreements where a deemed offer focuses on a sale to the company and the company fully or partially turns down the offer, the remaining shares are then offered to the other shareholders proportionate to their existing shareholding.

When such a clause is triggered, the venture’s other shareholders are generally given first option on the shares at a pro rata rate in relation to their existing shareholding. In the absence of an agreed-upon price for the shares, the shares would generally be offered at their fair market value.

The offer will then need to be accepted for it to be binding on the other shareholders. If the offer is not accepted, the deemed offer would fall away, meaning that the affected shareholder (or their legacies) would have full title to the shares.

Most shareholder agreements would generally contain a list of events concerning shareholders that would trigger a deemed offer. These events generally include, but are not limited to:

-

Death

-

Shareholder disability or incapacity

-

Insolvency

-

Sequestration in the case of natural persons

-

Liquidations/business rescue/administration in the case of juristic shareholders

-

Criminal convictions, etc.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll focus on death.

From the perspective of co-founders, shareholders, and external investors, deemed offer provisions play a vital role in maintaining an efficient capital structure. This framework ensures that, among other things, significant ownership stakes are held by active contributors who play a pivotal role in the company’s ongoing growth, as opposed to passive stakeholders. By doing so, these provisions prevent the dilution of ownership concentration and safeguard the overall ownership stake of existing shareholders.

In the case of a shareholder’s death, the estate’s executor, often unfamiliar with the business, can disrupt operations and risk business continuity, especially when the deceased held a significant stake in this business. Executors generally prioritise the liquidation of a deceased estate, potentially leading to the sale of the deceased shareholder’s shares (typically to the highest bidder) to external buyers. A more favourable outcome for surviving shareholders and/or the company is having the first option on whether they wish to purchase the deceased’s shareholding or not.

Navigating the crossroads of business and personal estate legacies

While a forced sale of a deceased founder’s shares may intend to secure business interests through a seamless transfer of ownership to surviving key stakeholders, the business’s interests don’t always align with those of the deceased founder’s personal legacy.

However well-intentioned, a forced sale triggered by a founder’s passing can harm the value of the founder’s personal estate. As such, it becomes crucial for founders to equip themselves with robust financial planning knowledge, striking a balance between business pursuits and the preservation of their personal estates.

Maintaining family interests during business succession requires skillfully balancing ongoing business operations and protecting the founder’s estate. It is, therefore, of paramount importance that the terms of shareholder agreements are crafted in a manner that protects both the founder’s interests and the company’s path forward.

To achieve this balance, active and intentional discussions between founders, other stakeholders, and investors must be had.

Negotiating deemed offer provisions: practical considerations

Within these negotiations, there are a number of options that founders can explore when it comes to keeping a deemed offer clause in place while doing right by their families.

One option is to explore partial deemed offers. Here, founders can negotiate for only a portion of their shares to be available for sale when a deemed offer occurs following their death. This measured approach ensures that the founder’s estate retains a stake in the business, allowing it to share in the venture’s future prosperity.

The portion of shares subject to a forced sale can then be negotiated with the remaining stakeholders. From an investor or existing shareholder’s perspective, the real risk in agreeing to such a compromise could be if, post-sale, the deceased estate continues to hold a significant portion of the venture’s shares, complicating voting etc. If a deceased estate holds just a passive or non-controlling interest in the business, it shouldn’t be that much of a concern.

Another option is to explore non-discounted deemed offers. It is quite common in deemed offer clauses for the remaining shareholders and the company has the first option to purchase the deceased’s shares first at a certain discount. While this can feel cold, it may be a necessary incentive for them to take advantage of the offer, simultaneously increasing their ownership and offering liquidity to the departing deceased shareholder’s estate. This approach streamlines the sale process and mitigates the need to involve new third-party buyers.

The discount generally varies from one transaction to another, depending on the influence held by the requesting shareholder (usually an investor and/or majority shareholder) and the bargaining power of other shareholders. While there is no guarantee that an investor would agree to a zero discount on a forced sale, a founding shareholder may attempt to negotiate for one or in the worst case, a reduced discount.

Needless to say, negotiating these options requires a sound understanding of the law and/or corporate transactions in general. As such, it is always recommended that founders seek the help of legal counsel to offer guidance tailored to individual circumstances.

Exploring alternative approaches

From a personal estate planning perspective, there could be other ways in which a founder can plan their affairs such that in the event of their death, there is business continuity and that the surviving shareholders are not prejudiced.

While the below does not constitute legal nor financial advice, here are some possible thoughts that could be unpacked with the help of a qualified finance or legal professional:

Buy-sell agreements

In this type of agreement, co-shareholders can take a life insurance policy to cover the lives of each other. In the unfortunate event of a co-shareholder’s passing, the life insurance pay-out can then facilitate the purchase of the deceased shareholder’s interest by the surviving co-shareholder.

Keyman insurance

Companies can opt for life insurance policies on key shareholders’ lives. In the event of an insured shareholder’s death, the insurance proceeds (generally payable to the company) can then fund the company’s repurchase of the shares held by the deceased shareholder.

The protective shield these products offer, by ensuring seamless transitions and business continuity, aligns well with the heightened responsibilities and higher stakes of more advanced startup phases. Therefore, while the cost factor might be a challenge initially, as startups grow and their financial capacity strengthens, these insurance products become strategic tools that warrant some consideration.

It pays to plan ahead

In the world of startups and visionary founders, balancing business success with family legacies requires careful planning. Deemed offer provisions in shareholder agreements play a vital role in this process. By negotiating thoughtfully and seeking expert advice, founders can chart a path that preserves both their business and personal legacies.

Thando Sibanda is the Deputy Head of Legal at Founders Factory Africa

Feature/OPED

Measures at Ensuring Africa’s Food Sovereignty

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

China’s investments in Africa have primarily been in the agricultural sector, reinforcing its support for the continent to attain food security for the growing population, estimated currently at 1.5 billion people. With a huge expanse of land and untapped resources, China’s investment in agriculture, focused on increasing local production, has been described as highly appreciable.

Brazil has adopted a similar strategy in its policy with African countries; its investments have concentrated in a number of countries, especially those rich in natural resources. It has significantly contributed to Africa’s economic growth by improving access to affordable machinery, industrial inputs, and adding value to consumer goods. Thus, Africa has to reduce product imports which can be produced locally.

The China and Brazil in African Agriculture Project has just published online a series of studies concerning Chinese and Brazilian support for African agriculture. They appeared in an upcoming issue of World Development. The six articles focusing on China are available below:

–A New Politics of Development Cooperation? Chinese and Brazilian Engagements in African Agriculture by Ian Scoones, Kojo Amanor, Arilson Favareto and Qi Gubo.

–South-South Cooperation, Agribusiness and African Agricultural Development: Brazil and China in Ghana and Mozambique by Kojo Amanor and Sergio Chichava.

–Chinese State Capitalism? Rethinking the Role of the State and Business in Chinese Development Cooperation in Africa by Jing Gu, Zhang Chuanhong, Alcides Vaz and Langton Mukwereza.

–Chinese Migrants in Africa: Facts and Fictions from the Agri-food Sector in Ethiopia and Ghana by Seth Cook, Jixia Lu, Henry Tugendhat and Dawit Alemu.

–Chinese Agricultural Training Courses for African Officials: Between Power and Partnerships by Henry Tugendhat and Dawit Alemu.

–Science, Technology and the Politics of Knowledge: The Case of China’s Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centres in Africa by Xiuli Xu, Xiaoyun Li, Gubo Qi, Lixia Tang and Langton Mukwereza.

Strategic partnerships and the way forward: African leaders have to adopt import substitution policies, re-allocate financial resources toward attaining domestic production, and sustain self-sufficiency.

Maximising the impact of resource mobilisation requires collaboration among governments, key external partners, investment promotion agencies, financial institutions, and the private sector. Partnerships must be aligned with national development priorities that can promote value addition, support industrialisation, and deepen regional and continental integration.

Feature/OPED

Recapitalisation Without Transformation is a Risk Nigeria Cannot Afford

By Blaise Udunze

In barely two weeks, Nigeria’s banking sector will once again be at a historic turning point. As the deadline for the latest recapitalisation exercise approaches on March 31, 2026, with no fewer than 31 banks having met the new capital rule, leaving out two that are reportedly awaiting verification. As exercise progresses and draws to an end, policymakers are optimistic that stronger banks will anchor financial stability and support the country’s ambition of building a $1 trillion economy.

The reform, driven by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) under Governor Olayemi Cardoso, requires banks to significantly raise their capital thresholds, which are set at N500 billion for international banks, N200 billion for national banks, and N50 billion for regional lenders. According to the apex bank, 33 banks have already tapped the capital market through rights issues and public offerings; collectively, the total verified and approved capital raised by the banks amounts to N4.05 trillion.

No doubt, at first glance, the strategy definitely appears straightforward with the idea that bigger capital means stronger banks, and stronger banks should finance economic growth. But history offers a cautionary reminder that capital alone does not guarantee resilience, as it would be recalled that Nigeria has travelled this road before.

During the 2004-2005 consolidation led by former CBN Governor Charles Soludo, the number of banks in the country shrank dramatically from 89 to 25. The reform created larger institutions that were celebrated as national champions. The truth is that Nigeria has been here before because, despite all said and done, barely five years later, the banking system plunged into crisis, forcing regulatory intervention, bailouts, and the creation of the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON) to absorb toxic assets.

The lesson from that experience is simple in the sense that recapitalisation without structural reform only postpones deeper problems.

Today, as banks race to meet the new capital thresholds, the real question is not how much capital has been raised but whether the reform will transform the fundamentals of Nigerian banking. The underlying fact is that if the exercise merely inflates balance sheets without addressing deeper vulnerabilities, Nigeria risks repeating a familiar cycle of apparent stability followed by systemic stress, as the resultant effect will be distressed banks less capable of bringing the economy out of the woods.

The real measure of success is far simpler. That is to say, stronger banks must stimulate economic productivity, stabilise the financial system, and expand access to credit for businesses and households. Anything less will amount to a missed opportunity.

One of the most critical issues surrounding the recapitalisation drive is the quality of the capital being raised.

Nigeria’s banking sector has reportedly secured more than N4.5 trillion in new capital commitments across different categories of banks. No doubt, on paper, these numbers may appear impressive. Going by the trends of events in Nigeria’s economy, numbers alone can be deceptive.

Past recapitalisation cycles revealed troubling practices, whereby funds raised through related-party transactions, borrowed money disguised as equity, or complex financial arrangements that recycled risks back into the banking system. If such practices resurface, recapitalisation becomes little more than an accounting exercise.

To avert a repeat of failure, the CBN must therefore ensure that every naira raised represents genuine, loss-absorbing capital. Transparency around capital sources, ownership structures, and funding arrangements must be non-negotiable. Without credible capital, balance sheet strength becomes an illusion that will make every recapitalisation exercise futile.

In financial systems, credibility is itself a form of capital. If there is one recurring factor behind banking crises in Nigeria, it is corporate governance failure.

Many past collapses were not triggered by global shocks but by insider lending, weak board oversight, excessive executive power, and poor risk culture. Recapitalisation provides regulators with a rare opportunity to reset governance standards across the industry.

Boards must be independent not only in structure but also in substance. Risk committees must be empowered to challenge executive decisions. Insider lending rules must be enforced without compromise because, over the years, they have proven to be an anathema against the stability of the financial sector. The stakes are high.

When governance fails, fresh capital can quickly become fresh fuel for old excesses. Without governance reform, recapitalisation risks reinforcing the very weaknesses it seeks to eliminate.

Another structural vulnerability lies in Nigeria’s increasing amount of non-performing loans (NPLs), which recently caused the CBN to raise concerns, as Nigeria experiences a rise in bad loans threatening banking stability.

Industry data suggests that the banking sector’s NPL ratio has climbed above the prudential benchmark of 5 per cent, reaching roughly 7 per cent in recent assessments. Many of these troubled loans are concentrated in sectors such as oil and gas, power, and government-linked infrastructure projects, alongside other factors such as FX instability, high interest rates, and the withdrawal of Covid-era forbearance, which threaten bank stability.

While regulatory forbearance has helped maintain short-term stability, it has also obscured deeper asset-quality concerns. A credible recapitalisation process must confront this reality directly.

Loan classification standards must reflect economic truth rather than regulatory convenience. Banks should not carry impaired assets indefinitely while presenting healthy balance sheets to investors and depositors.

Transparency about asset quality strengthens trust. Concealment destroys it. Few forces have disrupted Nigerian bank balance sheets in recent years as severely as exchange-rate volatility.

Many banks still operate with significant foreign exchange mismatches, borrowing short-term in foreign currencies while lending long-term to clients earning revenues in naira. When the naira depreciates sharply, these mismatches can erode capital faster than any credit loss.

Recapitalisation must therefore be accompanied by stricter supervision of foreign exchange exposure, as this part calls for the regulator to heighten its supervision. Banks should be required to disclose currency risks more transparently and undergo rigorous stress testing at intervals that assume adverse currency scenarios rather than best-case outcomes. In a structurally import-dependent economy, ignoring FX risk is no longer an option.

Nigeria’s banking system has long been characterised by excessive concentration in a few sectors and corporate clients, which calls for adequate monitoring and the need to be addressed quickly for the recapitalisation drive to yield maximum results.

Growth in most advanced economies comes from the small and medium-sized enterprises that are well-funded. Anything short of this undermines it, since the concentration of huge loans to large oil and gas companies, government-related entities, and major conglomerates absorbs a disproportionate share of bank lending. This has continued to pose a major threat to the system, as the case is with small and medium-sized enterprises, the backbone of job creation, which remain chronically underfinanced. This imbalance weakens the economy.

Recapitalisation should therefore be tied to policies that encourage credit diversification and risk-sharing mechanisms that allow banks to lend more confidently to productive sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, and technology rather than investing their funds into the government’s securities. Bigger banks that remain narrowly exposed do not strengthen the economy. They amplify its fragilities.

Nigeria’s macroeconomic conditions, which are its broad economic settings, are defined by frequent and sometimes sharp changes or instability rather than stability.

Inflation shocks, interest-rate swings, fiscal pressures, and currency adjustments are not rare disruptions; but they have now become a normal part of the economic environment. Despite all these adverse factors, many banks still operate risk models that assume relative stability. Perhaps unbeknownst to the stakeholders, this disconnect is dangerous.

Owing to possible shocks, and when banks increase their capital (recapitalisation), it is required that banks adopt more sophisticated risk-management frameworks capable of withstanding severe economic scenarios, with the expectation that stronger banks should also have stronger systems to manage risks and survive economic crises. In Nigeria today, every financial institution’s stress testing must be performed in the face of the economy facing severe shocks like currency depreciation, sovereign debt pressures, and sudden interest-rate spikes.

Risk management should evolve from a compliance obligation into a strategic discipline embedded in every lending decision.

Public confidence in the banking system depends heavily on credible financial reporting.

Investors, analysts, and depositors need to be able to understand banks’ true financial positions without navigating non-transparent disclosures or creative accounting practices, which means the industry must be liberated to an extent that gives room for access to information.

Recapitalisation provides an opportunity to strengthen the enforcement of international financial reporting standards, enhance audit quality, and require clearer disclosure of capital adequacy, asset quality, and related-party transactions. Transparency should not be feared. It is the foundation of trust.

One thing that must be corrected is that while recapitalisation often focuses on financial metrics, the banking sector ultimately runs on human capital.

Another fearful aspect of this exercise for the economy is that consolidation and mergers triggered by the reform could lead to workforce disruptions if not carefully managed. Job losses, casualisation, and declining staff morale can weaken institutional culture and productivity. Strong banks are built by strong people.

If recapitalisation strengthens balance sheets while destabilising the workforce that powers the system, the reform risks undermining its own economic objectives. Human capital stability must therefore form part of the broader reform strategy.

Doubtless, another emerging shift in Nigeria’s financial landscape is the rise of digital financial platforms that are increasingly changing how people access and use money in Nigeria.

Millions of Nigerians are increasingly relying on fintech platforms for payments, microloans, and everyday financial transactions. One of the advantages it offers is that these services often deliver faster and more user-friendly experiences than traditional banks. While innovation is welcome, it raises important questions about the future structure of financial intermediation.

The point here is that the moment traditional banks retreat from retail banking while fintech platforms dominate customer interactions, systemic liquidity and regulatory oversight could become fragmented.

The CBN must see to it that the recapitalised banks must therefore invest aggressively in digital infrastructure, cybersecurity, and customer experience, while cutting down costs on all less critical areas in the industry.

Nigerians should feel the benefits of recapitalisation not only in stronger balance sheets but also in faster apps, reliable payment systems, and responsive customer service.

As banks grow larger through recapitalisation and consolidation, a new challenge emerges via systemic concentration.

Nigeria’s largest banks already control a significant share of industry assets. Further consolidation could deepen the divide between dominant institutions and smaller players. This creates the risk of “too-big-to-fail” banks whose collapse could threaten the entire financial system.

To address this risk, regulators must strengthen resolution frameworks that allow distressed banks to fail without triggering systemic panic, their collapse does not damage the whole financial system, and do not require taxpayer-funded bailouts to forestall similar mistakes that occurred with the liquidation of Heritage Bank. Market discipline depends on credible failure mechanisms.

It must be understood that Nigeria’s banking recapitalisation is not merely a financial exercise or, better still, increasing banks’ capital. It is a rare opportunity to rebuild trust, strengthen governance, and reposition the financial system as a true engine of economic development.

One fact is that if the reform focuses only on capital numbers, the country risks repeating a familiar pattern of churning out impressive balance sheets followed by another cycle of crisis.

But the actors in this exercise must ensure that the recapitalisation addresses governance failures, asset quality concerns, risk management weaknesses, and transparency gaps; and the moment this is done, the banking sector could emerge stronger and more resilient.

Nigeria does not simply need bigger banks. It needs better banks, institutions capable of financing innovation, supporting entrepreneurs, and building economic opportunity for millions of citizens.

The true capital of any banking system is not just money. It is trust. And whether this recapitalisation ultimately succeeds will depend on whether Nigerians see that trust reflected not only in financial statements but in the everyday experience of saving, borrowing, and investing in the economy. Only then will bigger banks translate into a stronger nation.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

Feature/OPED

When Expertise Meets Politics: The Rejection of Professor Datonye Dennis by Lawmakers

By Meinyie Okpukpo

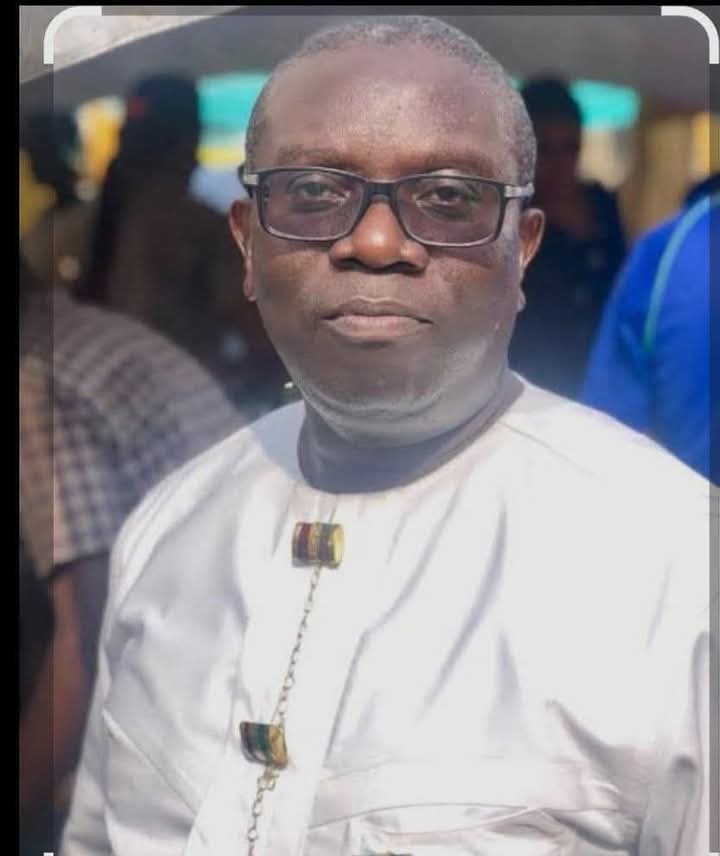

In a development that has generated debate within both political and medical circles in Rivers State, the Rivers State House of Assembly recently declined to confirm Professor Datonye Dennis Alasia as a commissioner-nominee submitted by the state governor, Siminalayi Fubara.

The decision followed a tense screening session in Port Harcourt and has raised broader questions about the intersection of politics, governance, and the role of technocrats in public administration.

For many in Nigeria’s medical community, Professor Alasia is not simply a nominee rejected by lawmakers. He is a respected physician, academic, and nephrology specialist whose decades-long career has contributed significantly to medical practice and training in the Niger Delta and across Nigeria.

The Political Drama Behind the Rejection

Professor Alasia was among nine commissioner nominees submitted by Governor Fubara to the Rivers Assembly as part of efforts to reconstitute the State Executive Council following the dissolution of the cabinet earlier in 2026. After deliberations, the Assembly confirmed five nominees but rejected four, including Professor Alasia.

During the screening exercise, lawmakers raised concerns about discrepancies in Alasia’s birth certificate as well as the absence of a tax clearance certificate among the documents he submitted to the Assembly. Although the professor offered explanations and apologised for the missing tax document, a motion was moved on the floor of the House recommending that he should not be confirmed. The Assembly subsequently voted against his nomination. Some lawmakers also cited what they described as “poor performance” during the screening exercise as part of the reasons for their decision. The outcome has since become one of the most talked-about developments from the commissioner screening exercise, largely because of Alasia’s distinguished professional background.

Who Is Professor Datonye Dennis Alasia?

Professor Alasia is widely known in Nigeria’s healthcare sector as a consultant nephrologist and Professor of Medicine with long-standing service at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH). At UPTH, he served as Chairman of the Medical Advisory Committee (CMAC), a key leadership position responsible for overseeing clinical governance, medical standards, and patient-care policies in one of Nigeria’s foremost teaching hospitals.

He also previously held the role of Deputy Chief Medical Director, contributing significantly to hospital administration and the implementation of medical policies within the institution.

In addition to his clinical responsibilities, Professor Alasia has been deeply involved in academic medicine, combining medical practice with teaching and research in the university system.

Advancing Nephrology Care in Nigeria

Professor Alasia specialises in nephrology, the branch of medicine that deals with kidney diseases. This area of medicine is particularly important in Nigeria, where hypertension and diabetes have contributed to a growing number of kidney failure cases.

Through his work as a consultant nephrologist, he has been involved in:

Diagnosis and treatment of kidney diseases

Management of chronic kidney failure

Development of nephrology services in tertiary hospitals

Training doctors in renal medicine

His contributions have helped expand specialised kidney care within the Niger Delta region.

Training the Next Generation of Doctors

Beyond clinical practice, Professor Alasia has also played an important role in medical education.

Teaching hospitals like UPTH serve as the backbone of Nigeria’s medical training system. Within this system, professors supervise:

Residency training programmes

Specialist physician development

Medical student education

Clinical research mentorship

Through these responsibilities, Professor Alasia has helped mentor and train numerous doctors who now practice across Nigeria and beyond.

Leadership in Hospital Administration

Professor Alasia’s role as Chairman of the Medical Advisory Committee at UPTH placed him at the centre of hospital governance.

The position involves responsibilities such as:

Oversight of clinical governance

Enforcement of patient-care standards

Coordination of medical departments

Implementation of healthcare policies

The CMAC position is widely regarded as one of the most influential clinical leadership roles in Nigerian teaching hospitals.

Politics Versus Professional Expertise

The rejection of Professor Alasia highlights a broader issue often seen in Nigerian governance—the tension between professional expertise and political scrutiny. On one hand, the Assembly maintains that its decision reflects its constitutional duty to thoroughly vet nominees and ensure that those appointed to public office meet all necessary requirements. On the other hand, some observers argue that professionals with long careers outside politics may sometimes struggle to navigate political screening processes that are often designed with career politicians in mind.

What Happens Next?

With four nominees rejected during the screening exercise, Governor Fubara may be required to submit new names to the Assembly in order to complete the composition of the State Executive Council.

For Professor Alasia, however, the Assembly’s decision does not diminish a career built over decades in medicine, medical education, and hospital administration.

Conclusion

Professor Datonye Dennis Alasia represents a class of Nigerian professionals whose influence lies primarily outside the political arena. As a professor of medicine, consultant nephrologist, and hospital administrator, his contributions to medical training and kidney disease management remain significant.

Yet his experience before the Rivers State Assembly reflects a recurring reality in Nigerian public life: even the most accomplished technocrats must still navigate the complex and often unforgiving terrain of politics.

Meinyie Okpukpo, a socio-political commentator and analyst, writes from Port Harcourt, Rivers State

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn