Feature/OPED

Nigerian Ecosystem of 4th Industrial Revolution & Craft of Working Institutions

By Oremade Oyedeji

When Nigeria’s President, Muhammadu Buhari, lashed out on the youth several months ago, describing them as lazy, it probably seemed to many as a political jingoism, but in all honesty, I personally think the President was 100 percent right. After all, our dear President is 76 years old. Who do we expect to fix the rot in this ecosystem we call Nigeria? That was harsh right? “issorite, kontiniu to move in drove en masse to Canada. Smiles!!!

Few weeks ago, I had this conversation with my friend Adeola, who had lived and studied in the UK before moving back to Nigeria recently, and he made a remark from an argument I think he had with another mutual friend few weeks back. They both saw on TV a veteran 66-year-old Nigerian actor, Kayode Odumosu, popularly known as Pa Kasumu. He was shown on TV in a terrible state of health. He has probably been struggling with his health since 2013, according to report from some quarters.

Adeola: OMG! Pa Kasumu was a fine Yoruba actor. (He said pitifully).

Jide (Not real name, our mutual friend) felt even more pitiful with his eye glued to the TV, (with a wish look of healing him with some spiritual powers of sort). Unconsciously, he said this country was doom, no good health system. “How can someone like this be sick to the point he is asking for public help in order to stay alive? That cannot happen in developed countries,” he exclaimed.

Adeola: hmmm…. (He sighed) what are you saying, is it government’s job to treat the sick man?

At this point, the conversation with Adeola touched something in me. So, I asked him whose responsibility it is. Now, he got a little sober. “I don’t know, maybe his family, health insurance scheme, his pension funds etc,” he said.

So, the question now is, how could he have benefited from any of those instituted schemes? I mean we all know the actor worked in a relatively informal entertainment sector, without an organized pension scheme or HMO. We all know what the position of the law, in respect to pension schemes and health scheme.

I remembered Dr Ngozi Okunjo-Iweala’s crusade about building a working institution in government when she was the then Coordinating Minister of the Economy. I also know recently, the pension reform act of 2014 has now expanded the contributory pension scheme (CPS) to accommodate self-employed and person working under employment of three employees and below. So, let’s just say that is a legislative relief.

Talking about the institutions; how efficient are the institutions of government in Nigeria? The truth is all the government institutions are weak, hmmm… I imagine you disagreeing with that, perhaps saying, why all? They are weak because of one major factor, which is the personnel (i.e the youth who supposedly work in these institutions). Other secondary reasons are the processes and maybe the law (i.e legal framework). I hope you now see what probably informed what the President said about the youth. The youth failed to initiate workable standards to various institutions of government where he or she works. That is why for example, Pa Pasunmu was sick and he probably didn’t have a working pension plan or an HMO plan that supports his career and age. These challenges cut across all ministries and departments of government, and the so-called regulators and standards setters.

Let me shock you, take accounting standard setters in Nigeria for instant, it is even worse. Strange right? Ask why the Nigerian accounting standard board that used to be the issuer of accounting standards in Nigeria (Statements of Accounting Standard (SAS) and the Nigerian Generally Accepted Accounting Principle (NGAAP) was abolished and replaced with foreign standards like IFRS of the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB). Did you say it’s the need for globalization if I heard you? That is not the absolute truth. Yes, the Financial Reporting Council Nigeria for example and maybe the banking ecosystem rejoice of the effect of that change maybe. But the truth is the Nigerian Accounting Standard Board was literarily not in existent. That ministry or department had employee who took turn to come to work monthly, they had mentally lazy youth who have practically no idea of the needs of users of standards the agency was meant to issue. The Board was only able to issue total working standards of barely 24 counts up till the time it was abolish, while its foreign counterpart (IFRS) that was eventually adopted had more than 40 applicable standards; that is more than just a weak institution, they were lazy.

What is the effect of not issuing relevant standards for example? I once had a client that owns a rubber plantation in Ogun State, Nigeria, and as part of pre-audit exercise, I reviewed the file. I notice the previous year audited balance sheet figure was too small. In preparing an account of this nature, you need to recognize the biological asset. At this time, Nigerian accounting standards had no treatment for biological asset; none of the 24 working standards issued at this time addressed biological asset of any farm in Nigeria. Imagine if listed Uber, Facebook or Google in the US is not having a relevant accounting treatment for its digital assets? Exactly! That’s how terrible it can look.

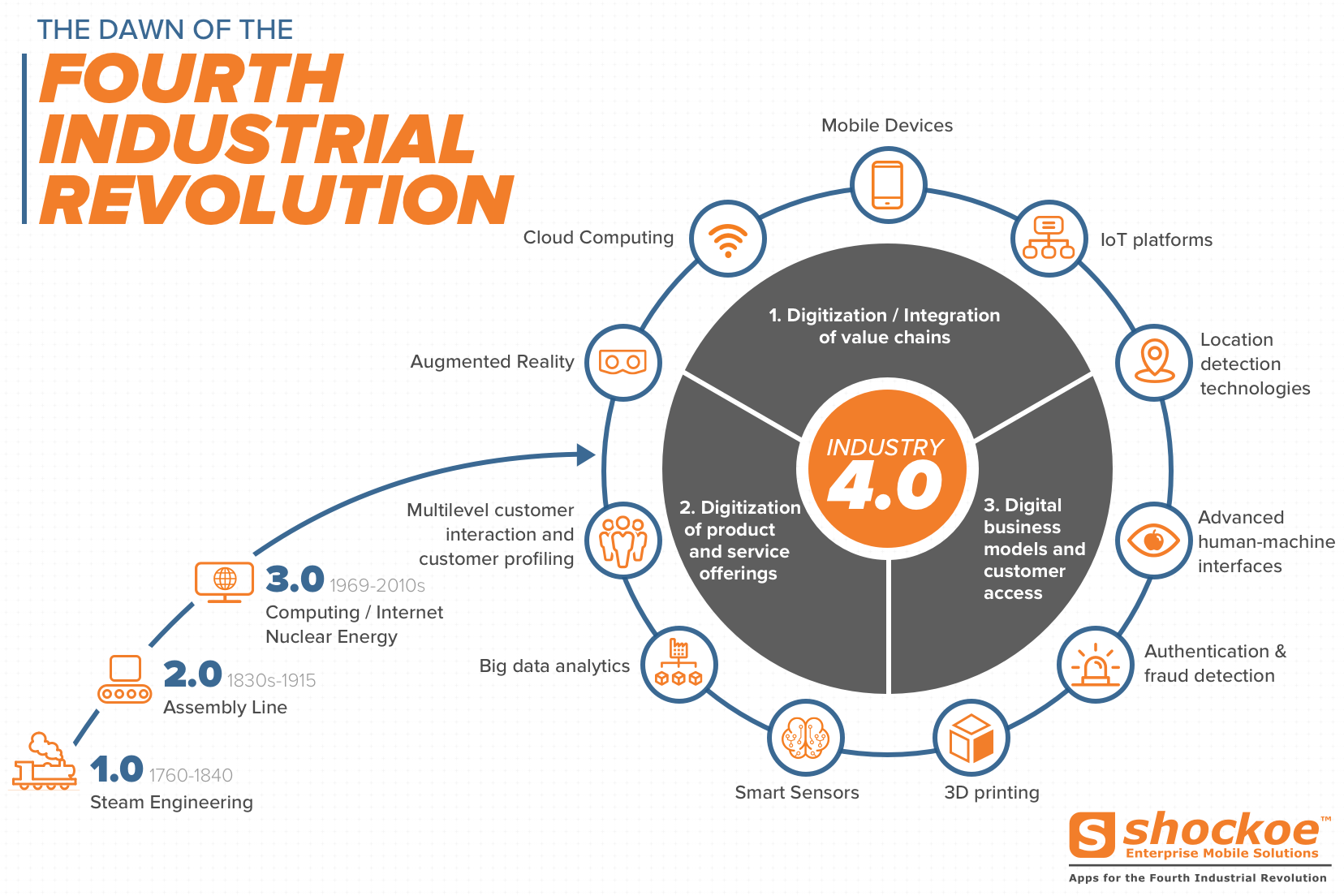

Fast forward; the fourth industrial revolution refers to a range of new technologies that fuse the physical, digital and biological worlds, impacting all disciplines, economies and industries, and even challenging ideas.

The key driving forces for the fourth industrial revolution include disruptive technologies; Internet of Things, Robotics, Artificial intelligence, Blockchain and Virtual Reality. The most relevant skills in this digital economic era will include professionals who have expertise in artificial intelligence, blockchain financials, cyber security and robotics.

Nigeria technically missed out in the three previous industrial revolutions. Well, the fourth industrial revolution is now in the hands of the vibrant youth. I think President Buhari was probably challenging the youth to wake up to the call against this disaster of missing out. What then is important is how to prevent this disaster from happening and the role IT educators need to play to ensure a smooth glide of the Nigerian economy in the fourth industrial revolution that will lead to mentioning this young Nigerian Robotic Engineer, Silas Adekunle, later in this article.

Let’s dwell a little on Dr Ngozi Okunjo Iweala, crusade of having the institutions working. Asides the ones earlier mentioned in this article, one of the examples of these institutions working in the country is the Nigerian Communication Commission (NCC).

NCC literally leaped from its comatose state of what it used to be in the 80s, an institution of less than 100,000 lines of both land and mobile in 1999, for a population of 160 million people, to what it is today, over 150 million active GSM lines, and already on the verge of releasing the 5G networks far ahead of Europe. Smiles! That the spirit of a Nigeria youth.

At no point in our almost 60-year history of independence has calls for Nigeria’s industrialization been stronger than they are today. Indeed, industrialization is one of the current administration’s priorities, given its acknowledged ability to bring prosperity, new jobs and better incomes for all. How then can Nigeria transform from an import-led economy that also relies on imported manufactured goods, to a producer and exporter of finished goods and services? Historically, Nigeria industrialization has been relatively slow, taking centuries to evolve as you noticed with telecoms for example.

The first industrial revolution began in the 18th and 19th century, when the power of steam and water dramatically increased the productivity of human (physical) labour. The second revolution started almost 100 years later with electricity as its key driver. Mass industrial production led to productivity gains, and opened the way for mass consumption. The third revolution followed, before Nigeria independence in the mid of 20th century with information technology: the use of computing in industry and the development of PCs. Today, we are witnessing the rise of the fourth industrial revolution.

What exactly is the Fourth Industrial Revolution?

I watched a video trending online of Silas Adekunle, a Nigeria young and Nigeria’s first robotic engineer, who built a robot from the scratch. In that interview, he mentioned three things that stood out; first was education, second was the ecosystem, and the third he mentioned was opportunity.

He particularly talked about problem solving in Nigeria’s ecosystem. He reiterated that the youth is expected to see the challenge of their environment and should learn robotics, with a view to proffering solution to Nigeria’s space in the course of their everyday life. For him, he believes robotics can help Nigeria in the area of security, learning, health, agriculture etc.

Silas is already predicting in few years from now when robots will speak Yoruba and probably other major Nigerian languages.

The Fourth Industrial revolution (4IR) combines technological and human capacities in an unprecedented way through self-learning algorithms, self-driving cars, human-machine interconnection, and big-data analytics. 4IR will gradually shape how we live, work and play.

How does Nigeria become 4IR-ready?

First, fast forward to the fifth industrial revolution. Let me share an illustration of Vice President Yemi Osinbajo in another video trending online. “Nobody dances like us, like it doesn’t matter whether you are the Senator of Kogi West or Osun West (concurrently on display was a dance floor music intro by King Sunny Ade ); (after a purse) or Africa richest man (now displaying on the screen was Aliko Dangote dancing to music by Teni titled Case, or the President of Africa’s largest economy President Muhammadu Buhari (displayed on screen was President Buhari dancing to life performance of King Wasiu Ayinde sometimes during election campaign in the west I think), and finally displayed on screen was a swag of former President Olusegun Obasanjo with the big dance. (laughs!!) My dear Vice President Osinbajo concluded that Nigerians love to dance. Smiles!!

Back to the sub-heading; For Nigeria to have the working institutions, she must fully harness the benefits of youthfully driven 4IR in the ministries and departments of governance; she must boost the country’s digital development. Therefore, a “Future Agenda” which promotes digital transformation in various institutions of government, and addresses necessary policies relating to relevant learning, entrepreneurship, agriculture, health and infrastructure etc in massive public private partnership (PPP) fusion.

In conclusion; in the fifth industrial revolution, human and machine will be dancing.

What are the Global Opportunities and Threats?

According to PwC, global GDP could increase by 14 percent in 2030 as a result of Artificial Intelligence (AI) & Robotics which is an additional $15.7 trillion. The 4IR is rapidly causing disruption by providing digital platforms for research, development, marketing, sales and distribution: all of which could drive efficiency and productivity while also reducing logistics and communication cost and creating new global supply chain channels.

Yet, the only opposing argument is that the 4IR can yield greater inequality to the economy because only the talented youths and not capital (and owners of capital) anymore, will become the major factor of production.

Another area of concern by some is the loss of jobs as automation begins to replace the unskilled and semi-skilled workforce. The good news is that while new technology may cause the creative destruction of some jobs, it will also create many new jobs, some of which we can’t even imagine today. The truth is that in the past, technology has ended up creating more jobs than it wiped out.

Feature/OPED

Daniel Koussou Highlights Self-Awareness as Key to Business Success

By Adedapo Adesanya

At a time when young entrepreneurs are reshaping global industries—including the traditionally capital-intensive oil and gas sector—Ambassador Daniel Koussou has emerged as a compelling example of how resilience, strategic foresight, and disciplined execution can transform modest beginnings into a thriving business conglomerate.

Koussou, who is the chairman of the Nigeria Chapter of the International Human Rights Observatory-Africa (IHRO-Africa), currently heads the Committee on Economic Diplomacy, Trade and Investment for the forum’s Nigeria chapter. He is one of the young entrepreneurs instilling a culture of nation-building and leadership dynamics that are key to the nation’s transformation in the new millennium.

The entrepreneurial landscape in Nigeria is rapidly evolving, with leaders like Koussou paving the way for innovation and growth, and changing the face of the global business climate. Being enthusiastic about entrepreneurship, Koussou notes that “the best thing that can happen to any entrepreneur is to start chasing their dreams as early as possible. One of the first things I realised in life is self-awareness. If you want to connect the dots, you must start early and know your purpose.”

Successful business people are passionate about their business and stubbornly driven to succeed. Koussou stresses the importance of persistence and resilience. He says he realised early that he had a ‘calling’ and pursued it with all his strength, “working long weekends and into the night, giving up all but necessary expenditures, and pressing on through severe setbacks.”

However, he clarifies that what accounted for an early success is not just tenacity but also the ability to adapt, to recognise and respond to rapidly changing markets and unexpected events.

Ambassador Koussou is the CEO of Dau-O GIK Oil and Gas Limited, an indigenous oil and natural gas company with a global outlook, delivering solutions that power industries, strengthen communities, and fuel progress. The firm’s operations span exploration, production, refining, and distribution.

Recognising the value of strategic alliances, Koussou partners with business like-minds, a move that significantly bolsters Dau-O GIK’s credibility and capacity in the oil industry. This partnership exemplifies the importance of building strong networks and collaborations.

The astute businessman, who was recently nominated by the African Union’s Agenda 2063 as AU Special Envoy on Oil and Gas (Continental), admonishes young entrepreneurs to be disciplined and firm in their decision-making, a quality he attributed to his success as a player in the oil and gas sector. By embracing opportunities, building strong partnerships, and maintaining a commitment to excellence, Koussou has not only achieved personal success but has also set a benchmark for future generations of African entrepreneurs.

His journey serves as a powerful reminder that with determination and vision, success is within reach.

Feature/OPED

Pension for Informal Workers Nigeria: Bridging the Pension Gap

***The Case for Informal Sector Pensions in Nigeria

***A Crucial National Conversation

By Timi Olubiyi, PhD

In Nigeria today, the phrase “pension” evokes many different mixed reactions. For many civil servants and people in the corporate world, it conjures a bit of hope, but for the majority in the informal sector, who are in the majority in Nigeria, it is bleak. Millions of Nigerians are facing old age without any financial security due to a lack of retirement plans and a stable pension plan. Particularly, the millions who operate in markets, corner shops, transportation, agriculture, and loads of the nano and micro scale enterprises operators are without pension plans or retirement hope.

From the observation of the author and available records, staggering around 90 per cent of Nigeria’s workforce operates in the informal economy. Yet current pension coverage for this group is virtually non-existent. As observed, the absence of meaningful pension participation by this class of worker reinforces the vulnerability, intensifies poverty among older people, and puts pressure on families who are ill-equipped to shoulder the burden.

The significance of having a pension plan for informal workers in Nigeria, given the large number of people in that sector and the high level of unemployment and underemployment, cannot be overstated. As it is deeply connected to sustenance and the level of poverty in the country. Pension for informal workers in Nigeria is not just a technical policy matter; it is a story about dignity, security, and whether a lifetime of hard work ends in rest or in desperation.

Nigeria’s pension system, primarily structured around the Contributory Pension Scheme (CPS) managed by the National Pension Commission (PenCom), has made significant progress for formal sector employees, yet the large portion of the informal workforce which are traders, artisans, okada riders, small-scale farmers, domestic workers, and gig economy participants who drive the real engine of the economy.

Though the Micro Pension Plan (MPP) was launched in 2019, which is intended to provide a voluntary contributory framework for informal workers, its uptake has been underwhelming; after several years, only a fraction of the millions targeted have enrolled, and far fewer contribute actively. One big reason for this is that, unlike formal workers who receive regular salaries and have employers who deduct and remit pension contributions, informal workers face irregular incomes, a lack of documentation, limited financial literacy, and deep mistrust of government institutions, making traditional pension models ill-suited for their realities.

Moreso the informal worker most times live on day-to-day income. For instance, a motorcycle rider in Lagos who earns ₦14,000 on a good day but must pay for fuel, bike maintenance, police “settlements,” and family expenses, how can he realistically commit to a monthly pension contribution when his income fluctuates wildly? So, the Micro Pension Plan for the informal sector participation will remain low due to poor awareness, complex processes, lack of tailored contribution flexibility, and limited trust.

To truly make pensions work for informal workers, Nigeria must rethink the system from the ground up, designing it around the lived realities of its people rather than forcing them into rigid formal-sector structures. First, the government should introduce a co-contributory model where the state matches a percentage of informal workers’ savings, similar to what is practised in some European countries, turning pension contributions into a powerful incentive rather than a burdensome obligation.

Second, digital technology must be leveraged aggressively—mobile-based pension platforms linked to BVN or NIN could allow daily, weekly, or micro-contributions as small as ₦100, integrating seamlessly with fintech apps like OPay, Paga, or bank USSD services so that saving becomes as easy as buying airtime.

Third, automatic enrollment through cooperatives, trade unions, market associations, and transport unions could significantly expand coverage, with opt-out rather than opt-in mechanisms to counter human inertia.

Fourth, financial literacy campaigns in local languages via radio, community leaders, and religious institutions are essential to rebuild trust and demonstrate that pensions are not a “government scam” but a personal safety net.

Fifth, Nigeria should consider a universal social pension for elderly citizens who never participated in formal or informal schemes, modelled after systems in countries like Denmark and the Netherlands, ensuring that no Nigerian dies in poverty simply because they worked outside formal structures.

Sixth, investment strategies for pension funds must prioritise both security and development—allocating a portion to infrastructure projects that create jobs, improve power supply, and stimulate economic growth while maintaining prudent risk management.

Seventh, inflation protection should be built into pension payouts so that retirees’ purchasing power is not eroded by Nigeria’s volatile economy.

Eighth, the system must be inclusive of women, who dominate the informal sector yet often lack property rights or formal identification, by simplifying documentation requirements and providing gender-sensitive outreach.

Ninth, limited emergency withdrawal options could be introduced—strictly regulated—to help contributors handle crises without abandoning the system entirely.

Finally, transparency and accountability are non-negotiable; regular public reporting, independent audits, and user-friendly dashboards would strengthen confidence that contributions are safe and growing. If Nigeria can blend its innovative spirit with lessons from global best practices—combining Denmark’s social security ethos, Singapore’s savings discipline, and Canada’s inclusivity—it could transform the lives of millions of informal workers who currently face retirement with fear rather than hope.

Imagine Aisha, years from now, closing her market stall not in exhaustion and anxiety but in calm assurance that her pension will cover her basic needs; imagine Tunde hanging up his helmet knowing he can afford healthcare and shelter; imagine Ngozi harvesting not just crops but the fruits of a lifetime of secure savings. The suspense that hangs over the future of Nigeria’s informal workers can be resolved, but only if policymakers act boldly, creatively, and compassionately—because a nation that allows its hardest workers to age in poverty is a nation that undermines its own prosperity, while a nation that secures their retirement builds not just pensions, but peace.

Hope comes from innovation. Fintech-powered pension models that allow small, frequent contributions similar to informal savings associations like esusu offer ways to integrate pensions into existing savings cultures. Making pension contributions compatible with mobile money and agent networks could drastically reduce barriers to entry. Hope comes from public education. Building financial literacy campaigns, partnering with community leaders, marketplaces, trade associations, and digital platforms can help shift perceptions. A pension should be understood not as a distant bureaucratic programme, but as future self-insurance and dignity

The significance of having a pension plan for informal workers in Nigeria, given its large informal sector and high level of unemployment and underemployment, cannot be overstated, as it is deeply connected to social stability, economic sustainability, poverty reduction, and national development.

First, from a social protection and human dignity perspective, a pension plan for informal workers is critical because it provides a safety net for old age. Nigeria’s informal sector includes traders, artisans, mechanics, tailors, hairdressers, okada riders, gig workers, domestic workers, small-scale farmers, and street vendors, many of whom work hard throughout their lives but have no formal retirement benefits. Without a pension, these individuals often become completely dependent on their children, relatives, or charity in old age, which can strain families and increase intergenerational poverty. A well-structured pension system ensures that ageing informal workers can maintain a basic standard of living, access healthcare, and avoid extreme deprivation, thereby preserving their dignity and reducing elderly vulnerability.

Second, from an economic stability and poverty reduction standpoint, pensions play a crucial role in reducing old-age poverty. Nigeria already struggles with high poverty levels, and a large proportion of elderly citizens without income support exacerbates this problem. When informal workers lack pension savings, they continue working well into old age, often in physically demanding jobs, which reduces productivity and increases health risks. A pension system allows for smoother retirement transitions, reduces reliance on welfare, and ensures that older citizens remain consumers rather than economic burdens, thereby sustaining economic activity.

Third, pensions for informal workers are significant for financial inclusion and savings culture. Many Nigerians in the informal sector operate primarily in cash and have limited engagement with formal financial institutions. A pension plan tailored to informal workers, especially one integrated with mobile money and digital platforms, can encourage regular saving, improve financial literacy, and bring millions of people into the formal financial system. This, in turn, strengthens Nigeria’s overall financial sector and increases the pool of domestic savings available for investment in infrastructure, businesses, and development projects.

Fourth, the significance is evident in reducing dependence on government emergency support. Currently, the Nigerian government often has to intervene with ad-hoc social assistance programs, especially during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation shocks, or economic downturns. If informal workers had functional pension savings, they would be better able to absorb economic shocks in retirement without relying heavily on government aid, reducing fiscal pressure on the state.

Fifth, pensions for informal workers contribute to intergenerational equity and family stability. In Nigeria, many elderly parents depend on their working children for survival, which places financial strain on younger generations who may already be struggling with unemployment, housing costs, and education expenses. A pension system reduces this burden, allowing younger Nigerians to invest in their own futures rather than being trapped in a cycle of supporting ageing relatives without external assistance.

Sixth, from a national development perspective, including informal workers in the pension system strengthens Nigeria’s long-term economic planning. Pension funds represent large pools of capital that can be invested in critical sectors such as housing, energy, transportation, and manufacturing. If millions of informal workers contribute even in small amounts, this could significantly expand Nigeria’s pension fund assets, providing stable, long-term financing for development projects that create jobs and stimulate growth.

Seventh, pensions for informal workers are important for gender equity, because women dominate many informal occupations in Nigeria, such as petty trading, market vending, tailoring, and caregiving roles. These women often have lower lifetime earnings, limited access to formal employment, and fewer assets. A targeted informal sector pension scheme can protect elderly women from destitution and reduce gender-based economic inequality in old age.

Eighth, the significance is also linked to public trust and governance. A transparent, accessible, and reliable pension system for informal workers can strengthen citizens’ trust in government institutions. Many informal workers currently distrust government programs due to past corruption, failed schemes, or poor implementation. A well-functioning pension plan that delivers real benefits would demonstrate that the state values all citizens, not just formal sector employees.

Lastly, given Nigeria’s demographic reality of a large and growing population, failing to integrate informal workers into a pension framework poses serious long-term risks. As life expectancy increases, the number of elderly Nigerians will rise significantly in the coming decades. Without a structured pension system for informal workers, Nigeria could face a severe old-age crisis characterised by mass poverty, social unrest, and increased pressure on healthcare and social services.

In summary, having a pension plan for informal workers in Nigeria is significant because it promotes social security, reduces poverty, enhances financial inclusion, supports economic stability, eases intergenerational burdens, strengthens national development, promotes gender equity, builds public trust, and prepares the country for its ageing population. For a nation where the majority of workers are informal, excluding them from pension coverage is not just an oversight; it is a major structural weakness that must be urgently addressed for Nigeria’s long-term prosperity and social cohesion.

Feature/OPED

Revived Argungu International Fishing Festival Shines as Access Bank Backs Culture, Tourism Growth

The successful hosting of the 2026 Argungu International Fishing Festival has spotlighted the growing impact of strategic public-private partnerships, with Access Bank and Kebbi State jointly reinforcing efforts to promote cultural heritage, tourism development, and local economic growth following the globally attended celebration in Argungu.

At the grand finale, Special Guest of Honour, Mr Bola Tinubu, praised the festival’s enduring national significance, describing it as a powerful expression of unity, resilience, and peaceful coexistence.

“This festival represents a remarkable history and remains a powerful symbol of unity, resilience, and peaceful coexistence among Nigerians. It reflects the richness of our culture, the strength of our traditions, and the opportunities that lie in harnessing our natural resources for national development. The organisation, security arrangements, and outlook demonstrate what is possible when leadership is purposeful and inclusive.”

State authorities noted that renewed institutional backing has strengthened the festival’s global appeal and positioned it once again as a major tourism and cultural platform capable of attracting international visitors and investors.

“Argungu has always been an iconic international event that drew visitors from across the world. With renewed partnerships and stronger institutional support, we are confident it will return to that global stage and expand opportunities for our people through tourism, culture, and enterprise.”

Speaking on behalf of Access Bank, Executive Director, Commercial Banking Division, Hadiza Ambursa, emphasised the institution’s long-standing commitment to supporting initiatives that preserve heritage and create economic opportunities.

“We actively support cultural development through initiatives like this festival and collaborations such as our partnership with the National Theatre to promote Nigerian arts and heritage. Across states, especially within the public sector space where we do quite a lot, we work with governments on priorities that matter to them. Tourism holds enormous potential, and while we have supported several hotels with expansion financing, we remain open to working with partners interested in developing the sector further.”

Reports from the News Agency of Nigeria indicated that more than 50,000 fishermen entered the historic Matan Fada River during the competition. The overall winner, Abubakar Usman from Maiyama Local Government Area, secured victory with a 59-kilogram catch, earning vehicles donated by Sokoto State and a cash prize. Other top contestants from Argungu and Jega also received vehicles, motorcycles and monetary rewards, including sponsorship support from WACOT Rice Limited.

Recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, the festival blends traditional fishing contests with boat regattas, durbar processions, performances, and international competitions, drawing visitors from across Nigeria and beyond.

With the 2026 edition concluded successfully, stakeholders say the strengthened collaboration between government and private-sector partners signals a renewed era for Argungu as a flagship cultural tourism destination capable of driving inclusive growth, preserving tradition, and projecting Nigeria’s heritage on the world stage.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn