Feature/OPED

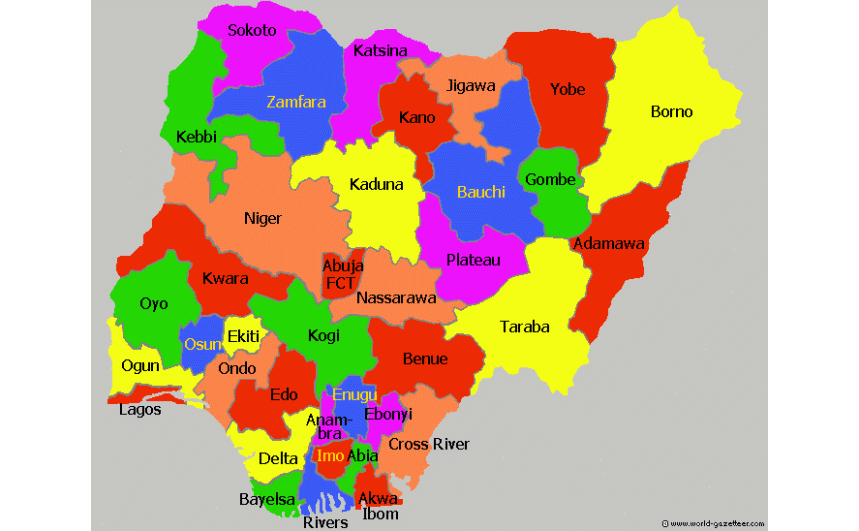

X-Raying Oragwu’s Suggestions on Nigeria’s Science and Technology Dilemma (II)

By Jerome-Mario Utomi

There are not only political but several technological obstacles that we collectively as a nation will determine how to overcome.

The origin of those technological challenges was in fact highlighted in the first part of this piece (READ IT HERE) and as a natural reaction, it is possible for readers that have gone through the first part, looking at what was presented, form opinions about the possible reason(s)/explanations fuelling the science and technology challenges in Nigeria.

Essentially, while some may conclude that such a challenge is rooted in the so-called mutual agreement which existed between Britain and the colonised Nigeria.

The rest may, however, heap the blame on the colonial masters’ heinous choice of giving Nigerians educations type that laid asymmetrical emphasis on certificates without substance.

Whichever way, to think that the above is the only possible explanation why Nigeria’s science and technology sector continues to have its headstock in the mud will amount to a false impression.

In fact, the challenge confronting the sector, as subsequent paragraphs will reveal, goes beyond the above considerations to include the effect of failures and obnoxious policies designed by successive administrations in post-independent Nigeria.

Such groundwork/‘atrocities’, according to a keynote address titled The Challenges of Science and Technology in Nigeria’s Economy: The Way Forward, delivered by FN Oragwu, in March 2018, at Eagle Square, Abuja, during an event organised by the National Agency for Science and Engineering Infrastructure (NASENI), that exacerbated the situation includes but not limited to; Nigeria’s failure to learn from the highly successful technological innovations experience that took place in the defunct state of Biafra,1967-1970: Nigeria’s inexplicable failure to appreciate the role of science and technology in safeguarding her political independence since 1960: Nigeria’s Faulty Economic Development Planning Strategy since 1962: and the failure to develop the pivotal electrical power supporting infrastructure for economic growth and development in Nigeria among others.

Adding context to the discourse, mutual agreement, as explained by the aforementioned address and used in the first part of this piece, is that arrangement or policy document that allowed Nigeria to export or supply Britain with primary agricultural commodities which Britain required for her once-famous textile industry and her leather and leather products industry, and to supply Britain with unprocessed natural minerals (solid, liquid and gaseous), which Nigeria has in abundance and which are of interest to Britain for the production and manufacture of technologies and industrial goods in the British economy.

Britain on her part is to “provide or export at costs to Nigeria, all the modern technologies and industrial goods that Nigeria needs to sustain her own economic growth and development.”

(Readers are equally encouraged to read The Dual Mandate of Europe in Tropical Africa, 4th Edition, London, 1929, by Lord Fredrick Lugard, first Nigeria’s Governor-General, 1914-1918).

With this highlighted, let’s focus on the aforementioned/outlined challenges.

The most serious and most surprising of such post-independent failures, going by the above address, is Nigeria’s failure to learn from the highly successful technological innovations experience that took place in the defunct State of Biafra, 1967-1970.

It was noted that the Nigerian scientists and engineers who found themselves in the defunct State of Biafra faced the daunting challenge of no domestic capacity for technology and industrial goods production which left the defunct State of Biafra scampering to import technologies and industrial goods but could not do so because of lack of foreign currency and blockade of a superior federal military government.

The address further said in part; it is this situation of no external support or assistance whatsoever during the civil war that forced the scientists/engineers/technicians to learn the hard way to produce technologies in Biafra.

The scientists and engineers had no choice but to adopt the strategy of technology innovation as earlier defined and through copy engineering design, copy components fabrication and copy technologies production and manufacturing creativity.

It is this strategy that enabled the scientists, engineers, technologists and technicians in Biafra, 1967-1970, to leapfrog within six months into domestic modern technology production/manufacturing capacity without any assistance and support whatsoever from the outside world.

The scientists/engineers, it was observed, were incredibly able to design and fabricate refineries for the production of petrol, diesel and kerosene, to produce effective weapon technologies, to construct airports among others which enabled the defunct State of Biafra to resist for 30 long months the awesome superior technology power of the federal military government.

This is the strategy that Japan used at the turn of the 20th Century to leapfrog into competition with awesome industrial Europe and North America. This is the same strategy that is now being used by countries such as China, India, South Korea and Brazil, to leapfrog into technology and industrial goods competition with top industrial Europe, North America and Japan.

It is, therefore, an inappropriate and hopeless task for Nigeria to continue to try to re-invent the wheel which Europe invented for us during the 18th and 19th Century industrial revolutions.

From the failure to learn from the highly successful technological innovations experience that took place in the defunct State of Biafra, flows something new and different.

It was emphasised that at Ghana’s Independence Day address, Dr Kwame Nkruma, the President of Ghana, reminded the Ghanaians that for economic reasons, Britain did not give Ghana the domestic endogenous capacity to produce and manufacture modern technologies and industrial goods in Ghana’s economy and that Ghana must acquire this capacity the hard way.

Without the domestic endogenous capacity for technologies and industrial goods production, Dr Nkruma stated in his Independence Day address, that “Ghana’s Independence would be meaningless”.

With this policy statement, Dr Kwame Nkruma directed that a Ghana Council for Scientific Research and Industrial Development be established to build and create the domestic endogenous capacity for the production of modern technologies and globally competitive industrial goods in Ghana’s economy for domestic use and for export. This is exactly what President Nehru of India was reported to have done at India’s Independence in 1947 and India is now one of the 20 top world industrial economies.

In contrast, it was underlined that no Nigerian political leader at whatever level, at our Independence Day address on October 1, 1960, said anything about the role of science and technology in safeguarding the independence of Nigeria and there was no mention of any relationship between science and technology and Nigeria’s economy.

All the energies of Nigeria’s political leaders since independence were seen to be consumed in fighting battles of ethnic nationality and religious differences. What Nigeria did in 1961 was to enter into military technology assistance agreement with the same departing British colonial power for protection, an action that led to protests by young Nigerians.

Nigeria’s poor economic development planning, which started from 1962 till date, is another contributing factor to the sector’s challenge identified by the keynote address.

They were based on foreign capital intensive technologies and on what funds were available to import these technologies and related industrial goods inputs and when the funds were not available as most times the case to import these foreign inputs, then the implementation of the plans failed.

There were no provisions in the plans for inputs from domestic produced technologies and industrial goods. Consequently, the domestic R&D/technology production agencies were left to do what they pleased and of course they simply revert to scientific research for knowledge acquisition which they know best and contributed nothing to the plans.

This is why Nigeria, with highly qualified and talented scientists and engineers equal to any in the world, cannot contribute any modern technologies or globally competitive industrial goods to Nigeria’s national economic development plans.

Away from the economic development plan, one more problem area necessary to the present discourse is the inability of successive administrations in the country to develop the pivotal electrical power supporting infrastructure for economic growth and development in Nigeria or learn from a country like the Republic of South Africa with a population of about 50 million as at 2011 but was generating 45,000 MW of electricity and is now the only member from Africa in the top 20 leading world economies.

Solutions proffered to this teaming challenge are the objective of the 3rd/final part.

To be continued.

Utomi Jerome-Mario is the Programme Coordinator (Media and Policy), Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA), Lagos. He could be reached via [email protected]/08032725374.

Feature/OPED

If Capital is the Answer, What Exactly is the Problem with First Holdco?

By Blaise Udunze

The Olayemi Cardoso-led Central Bank of Nigeria’s 24-month compliance timeline for the recapitalization of Nigeria’s banking system is about to conclude on March 31, 2026, which is framed as an unavoidable solution to systemic fragility, weak balance sheets, and the demands of a larger, more complex economy. Bigger capital, regulators argue, will produce stronger banks. Though First Bank may have met the CBN’s N500 billion minimum requirement, the latest financials from Femi Otedola-led First HoldCo Plc, which is the parent of Nigeria’s oldest commercial bank, offer a sobering counterpoint, revealing that capital alone cannot cure structural weakness, governance failure, or deep-rooted risk management flaws. If capital is the answer, what exactly is the problem?

What is truly astonishing to many is that beneath the headline growth in earnings lies a financial institution struggling with collapsing earnings quality, surging credit impairments, volatile fair-value exposures, and rising operating inefficiencies. First HoldCo’s numbers are not merely a company-specific disappointment; they are a mirror reflecting the deeper fault lines within Nigeria’s financial system and a warning that recapitalisation, in its current form, risks becoming another cosmetic reset rather than a genuine reform.

On the surface, the topline appears encouraging. The figures showed that gross earnings rose by 17.1 percent to N2.64 trillion in the nine months to 2025, while interest income surged by over 40 percent to N2.29 trillion. Figuring it out, investors, depositors, and analysts understand that these figures, however, are largely the product of a high-interest-rate environment driven by aggressive monetary tightening. They reflect repricing, not necessarily improved lending quality or superior balance-sheet strength. In an economy under strain, rising interest income often signals the transfer of macroeconomic stress from borrowers to banks, rather than sustainable growth.

This becomes evident once attention shifts from revenues to profitability. The performance disclosed that profit before tax declined by 7.3 percent to N566.5 billion, while profit after tax fell nearly 13 percent to N458 billion. Earnings per share dropped by a steep 27.7 percent, a sharper decline than headline profit suggests, pointing to dilution pressures and reduced value accruing to shareholders. More striking still is the full-year picture, where profit after tax from continuing operations collapsed by about 92 percent, plunging to N52.7 billion from N663.5 billion in the prior year. Such a dramatic fall cannot be explained by temporary volatility; it is the consequence of long-suppressed risks finally surfacing.

The most damaging of these risks is asset quality. The most critical figure is the impairment charges that rose by nearly 69 percent in the nine months to N288.9 billion, and by over 75 percent on a full-year basis to N748 billion, and invariably, these numbers tell a story of borrowers buckling under FX exposure, weak cash flows, and a deteriorating operating environment. They also raise uncomfortable questions about credit underwriting standards, concentration risk, and the effectiveness of internal risk controls in earlier lending cycles. After impairments, much of the benefit from higher interest income evaporated, exposing the fragility of earnings built on stressed credit.

Compounding this weakness was a sharp reversal in fair-value accounting. First HoldCo recorded a net loss of N87 billion on financial instruments measured at fair value, a stark contrast to the N549 billion gain recorded a year earlier. Due to this outcome, larger chunks of shareholders’ value were wiped out because this single swing accounted for a negative variance of over N636 billion year-on-year.

The episode highlights a dangerous dependence on market revaluations and FX-driven gains to prop up earnings, as seen that the moment conditions turn, paper profits vanish just as quickly, raising questions about the transparency, sustainability and economic substance of reported results.

Non-interest income provided little cushion. In the nine months to 2025, it declined by 44.5 percent, falling from N618.7 billion to N343.7 billion. While net fees and commission income rose by about 25 percent, the increase was too small to offset the collapse in other income lines. The result is a revenue base that is narrow, volatile, and overly exposed to market swings. Recapitalising banks without addressing this lack of income diversification simply amplifies vulnerability.

At the same time, operating costs surged. Operating expenses climbed by nearly 40 percent to N942.7 billion, while other operating expenses jumped over 43 percent on a full-year basis. Inflation, FX depreciation, energy costs, and technology spending all played a role, but the deeper issue is efficiency. Costs are rising far faster than sustainable income, eroding margins and weakening internal capital generation at precisely the moment banks are being asked to shore up capital buffers. Injecting fresh capital into institutions with broken cost structures does not resolve inefficiency; it merely postpones the inevitable days.

These financial stresses revive longstanding concerns about governance and risk culture in Nigeria’s banking system. Large impairment charges and valuation reversals do not emerge overnight. They accumulate through years of weak credit governance, excessive sector and obligor concentration, insider-related exposures, inadequate stress testing, and regulatory forbearance. Recapitalisation does not answer the most important questions: who gets credit, how risks are approved, how boards exercise oversight, and whether management is truly accountable. Without reform in these areas, more capital simply provides a thicker cushion for future losses.

Foreign exchange risk remains the system’s most dangerous and least resolved fault line. Currency devaluation inflates asset values and boosts interest income on paper, while simultaneously crushing borrowers with FX-denominated obligations. Banks may book translation or revaluation gains even as credit quality deteriorates beneath the surface. This contradiction fuels earnings volatility and undermines confidence in financial reporting. A stronger capital base does not neutralise FX mismatch risk; only disciplined risk management, credible macro policy, and transparent reporting can.

Perhaps most troubling is what First HoldCo’s results imply about regulatory credibility. Many of the impairments and valuation losses reflect risks that were visible long before they crystallised in the income statement. When losses arrive suddenly and in clusters, concerns from different quarters are raised and markets begin to question whether supervision is proactive or merely reactive. Recapitalisation without restoring trust in regulatory oversight risks being interpreted as an admission that deeper problems remain unaddressed and by extension, this erodes trust in the system and a stronger banking sector must also be a fairer and more accountable one.

Nigeria has travelled this road before. Bigger banks and higher capital thresholds have previously delivered reassuring headlines, only for familiar weaknesses to resurface in new forms. First HoldCo’s numbers demonstrate that capital adequacy, while necessary, is far from sufficient. Without the CBN confronting governance failures, asset quality deterioration, concentration risk, FX exposure, transparency gaps, and weak risk culture, recapitalisation risks will become another exercise in delay rather than reform.

The uncomfortable truth is that real stability requires more than fresh equity. It demands honest loss recognition, credible financial reporting, disciplined credit practices, diversified income streams, and regulators willing to enforce standards consistently. Until these missing pieces are addressed, recapitalisation will remain what it too often has been in Nigeria’s financial history, as a larger buffer for the same old problems, and a temporary comfort masking unresolved fragilities.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos, can be reached via: [email protected]

Feature/OPED

Why the Future of PR Depends on Healthier Client–Agency Partnerships

By Moliehi Molekoa

The start of a new year often brings optimism, new strategies, and renewed ambition. However, for the public relations and reputation management industry, the past year ended not only with optimism but also with hard-earned clarity.

2025 was more than a challenging year. It was a reckoning and a stress test for operating models, procurement practices, and, most importantly, the foundation of client–agency partnerships. For the C-suite, this is not solely an agency issue.

The year revealed a more fundamental challenge: a partnership problem that, if left unaddressed, can easily erode the very reputations, trust, and resilience agencies are hired to protect. What has emerged is not disillusionment, but the need for a clearer understanding of where established ways of working no longer reflect the reality they are meant to support.

The uncomfortable truth we keep avoiding

Public relations agencies are businesses, not cost centres or expandable resources. They are not informal extensions of internal teams, lacking the protection, stability, or benefits those teams receive. They are businesses.

Yet, across markets, agencies are often expected to operate under conditions that would raise immediate concerns in any boardroom:

-

Unclear and constantly shifting scope

-

Short-term contracts paired with long-term expectations

-

Sixty-, ninety-, even 120-day payment terms

-

Procurement-led pricing pressure divorced from delivery realities

-

Pitch processes that consume months of senior talent time, often with no feedback, timelines, or accountability

If these conditions would concern you within your own organisation, they should also concern you regarding the partner responsible for your reputation.

Growth on paper, pressure in practice

On the surface, the industry appears healthy. Global market valuations continue to rise. Demand for reputation management, stakeholder engagement, crisis preparedness, and strategic counsel has never been higher.

However, beneath this top-line growth lies the uncomfortable reality: fewer than half of agencies expect meaningful profit growth, even as workloads increase and expectations rise.

This disconnect is significant. It indicates an industry being asked to deliver more across additional platforms, at greater speed, with deeper insight, and with higher risk exposure, all while absorbing increased commercial uncertainty.

For African agencies in particular, this pressure is intensified by factors such as volatile currencies, rising talent costs, fragile data infrastructure, and procurement models adopted from economies with fundamentally different conditions. This is not a complaint. It is reality.

This pressure is not one-sided. Many clients face constraints ranging from procurement mandates and short-term cost controls to internal capacity gaps, which increasingly shift responsibility outward. But pressure transfer is not the same as partnership, and left unmanaged, it creates long-term risk for both parties.

The pitching problem no one wants to own

Agencies are not anti-competition. Pitches sharpen thinking and drive excellence. What agencies increasingly challenge is how pitching is done.

Across markets, agencies participate in dozens of pitches each year, with success rates well below 20%. Senior leaders frequently invest unpaid hours, often with limited information, tight timelines, and evaluation criteria that prioritise cost over value.

And then, too often, dead silence, no feedback, no communication about delays, and a lack of decency in providing detailed feedback on the decision drivers.

In any other supplier relationship, this would not meet basic governance standards. In a profession built on intellectual capital, it suggests that expertise is undervalued.

This is also where independent pitch consultants become increasingly important and valuable if clients choose this route to help facilitate their pitch process. Their role in the process is not to advocate for agencies but to act as neutral custodians of fairness, realism, and governance. When used well, they help clients align ambition with timelines, scope, and budget, and ensure transparency and feedback that ultimately lead to better decision-making.

“More for less” is not a strategy

A particularly damaging expectation is the belief that agencies can sustainably deliver enterprise-level outcomes on limited budgets, often while dedicating nearly full-time senior resources. This is not efficiency. It is misalignment.

No executive would expect a business unit to thrive while under-resourced, overexposed, and cash-constrained. Yet agencies are often required to operate under these conditions while remaining accountable for outcomes that affect market confidence, stakeholder trust, and brand equity.

Here is a friendly reminder: reputation management is not a commodity. It is risk management.

It is value creation. It also requires investment that matches its significance.

A necessary reset

As leadership teams plan for growth, resilience, and relevance, there is both an opportunity and a responsibility to reset how agency partnerships are structured.

That reset looks like:

-

Contracts that balance flexibility and sustainability

-

Payment terms that reflect mutual dependency

-

Pitch processes that respect time, talent, and transparency for all parties

-

Scopes that align ambition with available budgets

-

Relationships based on professional parity rather than power imbalance

This reset also requires discipline on the agency side – clearer articulation of value, sharper scoping, and greater transparency about how senior expertise is deployed. Partnership is not protectionism; it is mutual accountability.

The Leadership Question That Matters

The question for the C-suite is quite simple:

If your agency mirrored your internal standards of governance, fairness, and accountability, would you still be comfortable with how the relationship is structured?

If the answer is no, then change is not only necessary but also strategic. Because strong brands are built on strong partnerships. Strong partnerships endure only when both sides are recognised, respected, and resourced as businesses in their own right.

The agencies that succeed and the brands that truly thrive will be those that recognise this early and act deliberately.

Moliehi Molekoa is the Managing Director of Magna Carta Reputation Management Consultants and PRISA Board Member

Feature/OPED

Directing the Dual Workforce in the Age of AI Agents

By Linda Saunders

We will be the last generation to work with all-human workforces. This is not a provocative soundbite but a statement of fact, one that signals a fundamental shift in how organisations operate and what leadership now demands. The challenge facing today’s leaders is not simply adopting new technology but architecting an entirely new operating model where humans and autonomous AI agents work in concert.

According to Salesforce 2025 CEO research, 99% of CEOs say they are prepared to integrate digital labor into their business, yet only 51% feel fully prepared to do so. This gap between awareness and readiness reveals the central tension of this moment: we recognise the transformation ahead but lack established frameworks for navigating it. The question is no longer whether AI agents will reshape work, but whether leaders can develop the new capabilities required to direct this dual workforce effectively.

The scale of change is already visible in the data. According to the latest CIO trends, AI implementation has surged 282% year over year, jumping from 11% to 42% of organisations deploying AI at scale. Meanwhile, the IDC estimates that digital labour will generate a global economic impact of $13 trillion by 2030, with their research suggesting that agentic AI tools could enhance productivity by taking on the equivalent of almost 23% of a full-time employee’s weekly workload.

With the majority of CEOs acknowledging that digital labor will transform their company structure entirely, and that implementing agents is critical for competing in today’s economic climate, the reality is that transformation is not coming, it’s already here, and it requires a fundamental change to the way we approach leadership.

The Director of the Dual Workforce

Traditional management models, built on hierarchies of human workers executing tasks under supervision, were designed for a different era. What is needed now might be called the Director of the dual workforce, a leader whose mandate is not to execute every task but to architect and oversee effective collaboration between human teams and autonomous digital labor. This role is governed by five core principles that define how AI agents should be structured, deployed and optimised within organisations.

Structure forms the foundation. Just as organisational charts define human roles and reporting lines, leaders must design clear frameworks for AI agents, defining their scope, establishing mandates and setting boundaries for their operation. This is particularly challenging given that the average enterprise uses 897 applications, only 29% of which are connected. Leaders must create coherent structures within fragmented technology landscapes as a strong data foundation is the most critical factor for successful AI implementation. Without proper structure, agents risk operating in silos or creating new inefficiencies rather than resolving existing ones.

Oversight translates structure into accountability. Leaders must establish clear performance metrics and conduct regular reviews of their digital workforce, applying the same rigour they bring to managing human teams. This becomes essential as organisations scale beyond pilot projects and we’ve seen a significant increase in companies moving from pilot to production, indicating that the shift from experimentation to operational deployment is accelerating. It’s also clear that structured approaches to agent deployment can deliver return on investment substantially faster than do-it-yourself methods whilst reducing costs, but only when proper oversight mechanisms are in place.

To ensure agents learn from trusted data and behave as intended before deployment, training and testing is required. Leaders bear responsibility for curating the knowledge base agents access and rigorously testing their behaviour before release. This addresses a critical challenge: leaders believe their most valuable insights are trapped in roughly 19% of company data that remains siloed. The quality of training directly impacts performance and properly trained agents can achieve 75% higher accuracy than those deployed without rigorous preparation.

Additionally, strategy determines where and how to deploy agent resources for competitive advantage. This requires identifying high-value, repetitive or complex processes where AI augmentation drives meaningful impact. Early adoption patterns reveal clear trends: according to the Salesforce Agentic Enterprise Index tracking the first half of 2025, organisations saw a 119% increase in agents created, with top use cases spanning sales, service and internal business operations. The same research shows employees are engaging with AI agents 65% more frequently, and conversations are running 35% longer, suggesting that strategic deployment is finding genuine utility rather than novelty value.

The critical role of observability

The fifth principle, to observe and track, has emerged as perhaps the most critical enabler for scaling AI deployments safely. This requires real-time visibility into agent behaviour and performance, creating transparency that builds trust and enables rapid optimisation.

Given the surge in AI implementation, leaders need unified views of their AI operations to scale securely. Success hinges on seamless integration into core systems rather than isolated projects, and agentic AI demands new skills, with the top three in demand being leadership, storytelling and change management. The ability to observe and track agent performance is what makes this integration possible, allowing leaders to identify issues quickly, demonstrate accountability and make informed decisions about scaling.

The shift towards dual workforce management is already reshaping executive priorities and relationships. CIOs now partner more closely with CEOs than any other C-suite peer, reflecting their changing and central role in technology-driven strategy. Meanwhile, recent CHRO research found that 80% of Chief Human Resources Officers believe that within five years, most workforces will combine humans and AI agents, with expected productivity gains of 30% and labour cost reductions of 19%. The financial perspective has also clearly shifted dramatically, with CFOs moving away from cautious experimentation toward actively integrating AI agents into how they assess value, measure return on investment, and define broader business outcomes.

Leading the transition

The current generation of leaders are the crucial architects who must design and lead this transition. The role of director of the dual workforce is not aspirational but necessary, grounded in principles that govern effective agent deployment. Success requires moving beyond viewing AI as a technical initiative to understanding it as an organisational transformation that touches every aspect of operations, from workflow design to performance management to strategic planning.

This transformation also demands new capabilities from leaders themselves. The skills that defined effective management in all-human workforces remain important but are no longer sufficient. Leaders must develop fluency in understanding agent capabilities and limitations, learn to design workflows that optimally divide labor between humans and machines, and cultivate the ability to measure and optimise performance across both types of workers. They must also navigate the human dimensions of this transition, helping employees understand how their roles evolve, ensuring that the benefits of productivity gains are distributed fairly, and maintaining organisational cultures that value human judgement and creativity even as routine tasks migrate to digital labor.

The responsibility to direct what comes next, to architect systems where human creativity, judgement and relationship-building combine with the scalability, consistency and analytical power of AI agents, rests with today’s leaders. The organisations that thrive will be those whose directors embrace this mandate, developing the structures, oversight mechanisms, training protocols, strategic frameworks and observability systems that allow dual workforces to deliver on their considerable promise.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism9 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn