Health

How Nigeria Beat Ebola

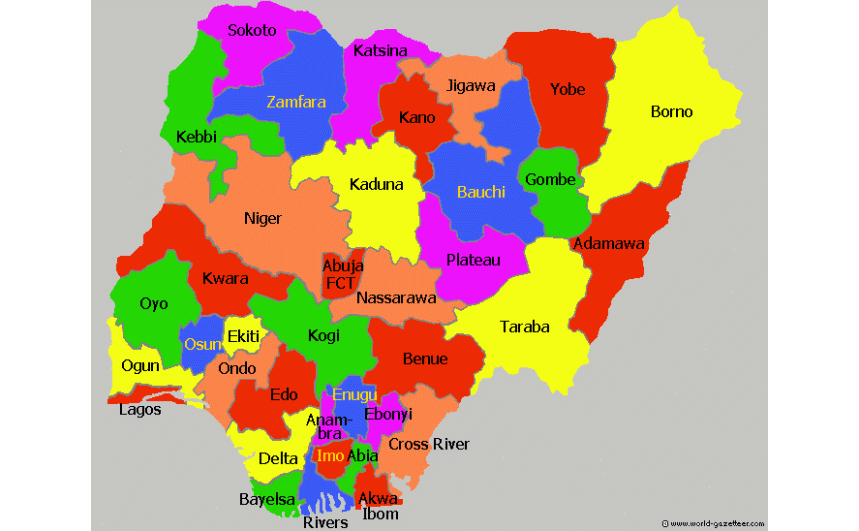

Nigeria has been Ebola-free since it narrowly avoided being sucked into the escalation of the highly contagious haemorrhagic fever outbreak which devastated its neighbours, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone resulting in the loss of over 11,000 lives.

WHO has commended the Nigerian Government for its strong leadership and effective coordination of the response that included the rapid establishment of an Emergency Operations Centre headed by Dr Faisal Shuaib, an advisor to the Minister for Health, who was at the centre of the country’s efforts to eradicate polio.

Dr Shuaib said: “The Government’s quick action and deployment of the necessary resources was key to averting a disaster. The circumstances were hugely challenging but we hit the ground running and there was good collaboration across all sectors involved. We were also fortunate in that Nigeria has a first rate virology laboratory affiliated with the Lagos University Teaching Hospital.”

The West Africa Ebola outbreak was the worst since the virus was first identified in 1976, and influenced the drafting of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction which emphasizes the need to enhance the resilience of national health systems and to integrate disaster risk management into health care.

Poverty, lack of preparedness and risk information, combined with inadequate health resources, made West Africa especially vulnerable, driving up exposure and fuelling the spread of the virus from March 2014 to January 2016 when WHO declared Liberia to be Ebola-free.

There was major alarm when the first case was reported in the sprawling Nigerian capital Lagos in July 2014, home to over 20 million people.

A diplomat who had been caring for a relative who died of Ebola in Liberia, and was already ill with the fever, managed to board a commercial fight to Lagos with the intention of visiting a faith healer.

He was admitted to a private hospital where he had to be physically restrained by a brave female doctor as he tried to flee the isolation unit. Both he and the doctor died. Matters were further complicated when another case was identified in the bustling oil centre of Port Harcourt.

Dr Margaret Lamunu, a veteran of WHO’s work on disease control in humanitarian crises, saw her family once during the 15 months she worked on the Ebola crisis. She was re-deployed from Sierra Leone to support the response in Nigeria when the news broke of the first case.

Commenting on the experience, Dr Lamunu said: “There was a huge difference in response capacity in Nigeria and what was possible in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia where you can almost count the numbers of doctors on one hand.

“In Nigeria we had people with Masters degrees doing the tracing work and there was no shortage of qualified medical personnel and lab facilities. All the resources necessary were mobilised quickly. The national Government, the public, partners, and the global community were concerned about it getting out of control.

“There was great detective work in tracking down hundreds of contacts and the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health, CDC (US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention), Médecins Sans Frontières, the Nigerian Red Cross and many other partners deserve much credit for how they managed to contain the risk of a major health disaster.”

A total of 894 contacts were linked directly to the original case. A further 526 contacts were linked to a health care worker who died in Port Harcourt. Altogether 18,500 face-to-face visits were carried out to check for fever and other symptoms. The high rate of literacy in the general population made it easier to carry out information campaigns by comparison with Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

By the time Nigeria was declared Ebola-free in October 2014, there were 19 infected individuals in addition to the index case from Liberia, 7 of whom died. These included eleven health care workers, 5 of whom paid the ultimate price for their courageous and successful efforts at containing the epidemic.

Dr Chadia Wannous, UNISDR health focal point, noted: “The experience of Nigeria when contrasted with that of other affected countries underlines how important it is to enhance the capacity of low-income developing countries to manage not just emergencies and disasters but the underlying risks. This requires resilient health systems with trained personnel, risk information and risk communication systems, logistics and supply chain structures, financing mechanisms and solid health governance as we have seen in Nigeria.”

She also highlighted the significant role played by the community, with teams of “social mobilizers” reaching thousands of households with health information and facilitating understanding so that fear and mistrust do not hinder mounting an effective response.

UNISDR is currently collaborating with WHO, UNDP and other partners to implement a project in Ebola-affected Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea to “accelerate the implementation of the Sendai Framework with risk-informed health systems”.

The project, funded by the government of Japan, aims to enhance collaboration between disaster risk management and health authorities and integrate health into disaster risk management structures and at the same time integrate risk management into the health sector. By doing so, it is expected that the project will further contribute to reducing mortality due to health emergencies and other types of disasters.

Reducing global disaster mortality is the theme of this year’s International Day for Disaster Reduction, October 13.

Health

Union Disrupts NAFDAC Operations in Lagos Over Sachet Alcohol Ban

By Adedapo Adesanya

Members of the National Union of Food, Beverage and Tobacco Employees protested at the Lagos office of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), disrupting operations in reaction to the ban on sachet alcohol.

The protesting union members barricaded the agency’s premises in Isolo, meaning staff who arrived early to resume duty were forced to remain outside the complex.

Recall that NAFDAC has continued the ban on alcoholic beverages sold in sachets and PET bottles below 200 millilitres, despite calls from certain quarters, including the picketers.

The union is demanding the immediate unsealing of affected factories and production lines, warning that sustained enforcement of the policy could trigger significant economic consequences across the industry.

It is the second time this month that union members disrupted the Lagos NAFDAC office over what they described as the agency’s refusal to comply with an alleged federal government directive to suspend enforcement of the ban on the production and sale of alcoholic beverages in sachets.

The union claimed that directives had been issued by the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation and the Office of the National Security Adviser, calling for the suspension of enforcement and the reopening of sealed production lines.

However, NAFDAC dismissed the claims, maintaining that it had not received any official instruction from the Federal Government to halt enforcement of the ban on sachet and PET-bottled alcohol.

Meanwhile, police officers were later seen at the NAFDAC Isolo premises, which dispersed the blockade to allow NAFDAC staff back into the premises.

Representatives of the Director-General of NAFDAC later engaged the protesting union in talks, but the meeting ended without resolution as demonstrators insisted their agitation would continue.

Union leaders presented their concerns during closed-door discussions with a director within the agency and the Special Assistant to the Director-General. However, no agreement was reached.

The protesters are urging NAFDAC to reconsider what they describe as the strict enforcement of the ban on sachet alcohol. Instead, they want the agency to focus on regulating access to such products, particularly by restricting sales to minors, while intensifying public enlightenment campaigns on responsible consumption.

Despite this, protesters say they will not stop until their demands are addressed.

Health

Modern Veterinary Clinics For Advanced Pet Care

As companion animals live longer and owners expect more from routine care, modern veterinary clinics have evolved into centers offering advanced diagnostics, specialty surgery, and integrative therapies. For busy professionals juggling work, travel, and online business demands, knowing which clinic delivers comprehensive care is essential. Frisco vet services illustrate how these modern practices combine cutting-edge technology, multidisciplinary expertise, and client-focused workflows. This article outlines the infrastructure, service offerings, and decision criteria that indicate a clinic capable of providing contemporary, evidence-based care while keeping visits efficient and stress-free for both pets and owners.

What Defines A Modern Veterinary Clinic

A modern veterinary clinic is defined less by a single piece of equipment and more by an integrated approach that combines up‑to‑date technology, specialized staff, and clinic design that prioritizes safety and comfort. These clinics treat animals with complex conditions, run efficient workflows, and communicate transparently with owners.

Key Infrastructure And Technology Investments

Contemporary clinics invest strategically in diagnostic and treatment modalities that materially change outcomes: digital radiography for rapid imaging, in‑house laboratories for same‑day blood work, ultrasound for real‑time organ assessment, and advanced surgical suites with anesthesia monitoring. Investment also includes infection‑control systems, reliable HVAC, and sterilization equipment. These capital decisions reduce turnaround time for diagnoses and support complex procedures that previously required referral.

Staffing, Specialization, And Continuing Education

Staffing reflects clinical ambition: veterinarians with specialty training (DACVS, DACVIM, DACVECC), certified veterinary technicians, and support staff trained in low‑stress handling. Modern clinics often host visiting specialists or maintain referral relationships with tertiary centers. Importantly, clinics that prioritize continuing education schedule regular training, subscribe to current literature, and engage in case reviews, actions that keep protocols current and improve outcomes.

Clinic Design For Safety, Flow, And Comfort

Design matters. Logical patient flow minimizes cross‑contamination and stress: separate entrances for healthy and sick patients, dedicated isolation wards, and distinct surgical zones. Comfortable client areas, clear signage, and private consultation rooms improve communication and compliance. For pets, non‑slip surfaces, quiet recovery areas, and pheromone‑friendly environments reduce anxiety, which in turn improves diagnostic accuracy and post‑procedure recovery.

Advanced Diagnostic Capabilities

Diagnostics are the backbone of modern pet care. Faster, more precise tests enable tailored treatment plans and earlier interventions.

Advanced Imaging: Digital X‑Ray, Ultrasound, CT, And MRI

Digital X‑ray provides high‑resolution images with immediate availability and easier sharing for remote consults. Ultrasound is indispensable for soft‑tissue evaluation and guided biopsies. CT and MRI, once exclusive to academic centers, are now present in many referral clinics, allowing detailed assessment of complex fractures, thoracic disease, neurologic conditions, and staging of cancer. Image quality and interpretation, often augmented by teleradiology, lead to more confident surgical planning and prognostication.

Laboratory, Point‑Of‑Care Testing, And Genomic Diagnostics

In‑house labs produce same‑day CBCs, chemistry panels, and cytology, accelerating decision‑making. Point‑of‑care tests for infectious agents, endocrine disorders, and clotting function add convenience without sacrificing reliability. Genomic diagnostics, from breed‑specific risk panels to tumor genomics, are increasingly accessible, enabling targeted therapies and risk stratification for hereditary conditions.

How Diagnostics Inform Preventive Care And Personalized Medicine

Diagnostics underpin preventive medicine: heartworm antigen tests, thyroid screening, and wellness blood panels reveal problems before clinical signs appear. Personalized medicine emerges when diagnostics inform individualized vaccination schedules, dietary plans, or monitoring frequency. The result: care that reduces emergency visits and improves long‑term quality of life.

State‑Of‑The‑Art Surgical And Interventional Services

Surgery in modern clinics spans routine spays and neuters to complex orthopedic reconstructions and image‑guided interventions.

Minimally Invasive, Laser, And Image‑Guided Procedures

Minimally invasive techniques, arthroscopy, laparoscopy, and endoscopy, reduce pain, shorten hospital stays, and speed return to function. Laser surgery provides precision and reduced bleeding for soft‑tissue procedures. Image‑guided interventions, such as CT‑guided biopsies or fluoroscopy for foreign body retrieval, allow targeted treatments that were once riskier or impossible.

Anesthesia, Pain Management, And Perioperative Safety

Anesthesia protocols are more nuanced today: individualized drug selection, multimodal analgesia, regional blocks, and continuous monitoring (ECG, capnography, pulse oximetry) improve safety. Preoperative assessment, including risk stratification and optimization of comorbidities, reduces complications. Recovery protocols emphasize early mobilization and aggressive pain control to prevent chronic pain syndromes.

Postoperative Rehabilitation And Recovery Protocols

Rehabilitation is an expected component of surgical care. Physical therapy, hydrotherapy, and tailored exercise plans reduce muscle atrophy and improve joint function. Clinics often provide home‑care instructions and scheduled reassessments to track progress and adjust protocols. These programs turn good surgical outcomes into durable functional gains.

Petfolk Veterinary & Urgent Care – Frisco

Advanced Therapeutics And Specialty Treatments

Beyond diagnostics and surgery, modern clinics deliver advanced therapeutics that extend and improve life quality.

Regenerative Medicine: Stem Cells And PRP

Regenerative modalities like mesenchymal stem cell therapy and platelet‑rich plasma (PRP) injections aim to stimulate healing in tendon, ligament, and osteoarthritic conditions. While still an evolving field, controlled studies and clinical experience show promising functional improvements for select patients. Clinics offering these therapies combine careful case selection with measurable outcome tracking.

Oncology, Neurology, Cardiology, And Other Specialties

Specialty services allow complex, multidisciplinary care. Veterinary oncologists provide staging, chemotherapy, and radiation planning: neurologists manage seizure disorders and spinal disease: cardiologists use echocardiography and interventional procedures for congenital heart defects. Integration with imaging and lab diagnostics enables cohesive care pathways that mirror human tertiary centers.

Integrative Therapies: Physical Rehab, Acupuncture, And Nutrition

Integrative care recognizes the value of adjunctive treatments. Acupuncture and targeted nutrition plans complement medical therapy for chronic pain and mobility issues. Nutritional counseling, including therapeutic diets for renal, cardiac, or dermatologic disease, is standard in clinics focused on long‑term outcomes.

Improving Pet And Client Experience With Technology

Technology enhances both clinical care and client experience, especially for owners who need efficient, transparent services.

Telemedicine, Remote Monitoring, And Virtual Follow‑Ups

Telemedicine extends access for triage, follow‑ups, and behavioral consultations. Remote monitoring devices, activity trackers, continuous glucose monitors, and wearable ECGs, provide objective data between visits. Virtual follow‑ups reduce travel burdens and let clinicians adjust care in real time, improving adherence and satisfaction.

Electronic Medical Records, Client Portals, And Scheduling Tools

Electronic medical records (EMRs) streamline documentation and support coordinated care. Client portals give owners access to vaccination histories, lab results, and discharge instructions. Integrated scheduling and automated reminders decrease no‑shows and improve preventive care compliance, a benefit both to clinics and busy clients.

Pain Management, Behavior‑Based Care, And Low‑Stress Handling

Client experience is inseparable from pet comfort. Modern clinics train staff in low‑stress handling techniques and behavior‑based protocols that reduce fear and aggression. Transparent pain‑management plans, clear cost estimates, and follow‑up communications foster trust and better outcomes.

How To Choose The Right Modern Clinic For Your Pet

Choosing a clinic requires practical criteria and an understanding of trade‑offs between convenience, specialization, and cost.

Questions To Ask: Credentials, Equipment, And Outcomes

Prospective clients should ask about specialist credentials, the availability of imaging and lab services, and the clinic’s approach to anesthesia and pain control. Request examples of similar cases and expected outcomes. A clinic that welcomes such questions is often more transparent and results‑oriented.

Cost, Insurance, And Referral Pathways

Advanced care carries higher costs. Discuss fee structures, payment options, and whether the clinic works with pet insurance. Understand referral pathways: does the clinic refer to or host board‑certified specialists? Clear referral and co‑management policies indicate maturity and a networked approach to care.

Evaluating Reviews, Accreditation, And Collaboration With Primary Vets

Look for consistent reviews that mention communication, follow‑up, and outcomes rather than isolated flashy cases. Accreditation (AAHA in the U.S.) or affiliation with universities can signal adherence to higher standards. Finally, the best specialty clinics collaborate with primary care veterinarians, ensuring continuity rather than competition.

Conclusion

Modern veterinary clinics for advanced pet care combine technology, specialization, and thoughtful design to deliver better diagnostic accuracy, safer surgeries, and more personalized therapies. Pet owners benefit when clinics pair capabilities with clear communication, transparent costs, and collaborative care models. For professionals, including small business owners and busy entrepreneurs who value efficient, outcome‑driven services, selecting a clinic that integrates advanced diagnostics, robust perioperative care, and client‑centric technology yields the best chance for sustained pet health. As veterinary medicine continues to mirror human healthcare in capability and complexity, informed choices and trusted partnerships between owners and clinics will determine the real value of those advances.

Health

Oyo Seals Ar-Rahmon Khabul Herbal Over Health Concerns

By Modupe Gbadeyanka

An Ibadan-based herbal company, Ar-Rahmon Khabul Herbal Nigeria Limited, has been sealed by the Oyo State Rule of Law Enforcement Authority (OYRLEA).

The state government, in a statement signed on Friday by the Commissioner for Information, Mr Dotun Oyelade, revealed that the herbal firm was shut down due to environmental violations and public health concerns.

The leader of OYRLEA, Mrs Aderonke Aderemi, explained that the action was taken after multiple petitions from residents alleging persistent offensive odour and health challenges linked to the company’s operations.

She noted that the state government swung into action “to protect public health, preserve environmental standards, and enforce regulatory compliance across the state.”

It was gathered that investigations identified tobacco leaf as a major component in its production process, generating a strong, putrid odour deemed hazardous to residents and capable of posing serious health risks to the surrounding community.

“Joint inspections by officials revealed that the company operates a herbal production facility within a densely populated residential area, in clear violation of environmental and public health standards,” the statement said, adding that further findings from the inspection include the emission of harmful and toxic gaseous substances into the atmosphere, the discharge of wastewater into a nearby community water body, the installation of a chimney deemed too short and directly facing residential buildings, and the accumulation of solid waste within the premises despite claims of engaging a waste contractor, among others.

Prior to the enforcement action, the agency had issued an abatement notice directing the company to cease operations and relocate within 21 days in accordance with the Oyo State Environmental, Sanitation and Waste Control Regulations.

OYRLEA, along with the agencies that carried out the enforcement, reiterates that air pollution, hazardous waste discharge, and improper waste management are violations of environmental laws.

Mrs Aderemi reaffirmed OYRLEA’s commitment to sustained monitoring and enforcement to ensure a safe and healthy environment for all residents.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn