World

700 Civilians Already Killed In DR Congo Attack—HRW

By Dipo Olowookere

The Human Rights Watch (HRW) has urged government of the Democratic Republic of Congo to protect civilians in Beni from attacks.

Unidentified fighters have killed nearly 700 civilians in a series of massacres that began two years ago in Beni territory in eastern DRC, the HRW said on Friday.

In one of the largest recent attacks, on August 13, 2016, fighters killed at least 40 people and set fire to several homes in the Rwangoma neighbourhood in the town of Beni, despite a large presence of Congolese army soldiers and United Nations peacekeepers.

“The Congolese government and UN peacekeepers need a new strategy to protect civilians in Beni and to hold those responsible for attacks to account,” said Ida Sawyer, senior Africa researcher at HRW. “After two years of brutal killings, many people in Beni live in fear of the next attack and have all but lost hope that anyone can end the carnage.”

Human Rights Watch research and credible reports from Congolese activists and the UN indicate that armed fighters have killed at least 680 civilians in at least 120 attacks in Beni territory since October 2014.

Victims and witnesses described brutal attacks in which assailants methodically hacked people to death with axes and machetes or shot them dead. The actual number of victims could be much higher.

It is unclear who is carrying out the attacks. The Congolese government blames one armed group that has been active in the area, while other sources have also implicated other groups and army officers in some of the attacks.

The Human Rights Watch findings are based on five research trips to Beni territory since November 2014, and interviews with over 160 victims and witnesses to attacks, as well as with Congolese army and government officials, UN officials, and others.

A 10-year-old boy said that he had been taken hostage during the Rwangoma attack and witnessed several killings: “Men in military uniform came and took me and my big brother and grandmother. …They tied us up and made us walk with them. Along the way, they started to kill some of us, including my 16-year-old brother. They killed him and some of the others with axes and machetes.”

Congolese army soldiers and UN peacekeepers only deployed to the area after the attack had ended and the assailants had long fled.

Human Rights Watch documented other incidents in which community members had alerted the army, but it did not respond.

In one case, on July 4, 2016, four local farmers warned the army about the suspicious presence of armed men near the town of Oicha, 30 kilometres north of Beni.

The farmers later told Human Rights Watch how an army officer responded: “We have taken all necessary measures to respond to all eventualities. Go home but don’t tell anyone. Don’t scare people for no reason.” The next morning, unidentified fighters fired shots in Oicha. Later, the bodies of nine gunshot victims were found close to two army positions in town.

An army officer based in Oicha told Human Rights Watch that some soldiers were angry when their superior ordered them to leave a nearby position and not engage the assailants as the attack was unfolding.

Senior UN and Congolese army officials have repeatedly asserted that the attacks in Beni territory have been carried out by the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a Ugandan-led Islamist rebel group that has been in the area since 1996.

Human Rights Watch research and findings by the UN Group of Experts on Congo, the New York-based Congo Research Group, and Congolese human rights organizations, however, point to the involvement of other armed groups and certain Congolese army officers in planning and carrying out some of these attacks.

ADF fighters from Uganda and Congo have been responsible for scores of kidnappings, mostly for recruitment or carrying goods in recent years, Human Rights Watch said.

Civilians who had earlier been held in ADF camps told Human Rights Watch they saw deaths by crucifixion, executions of those trying to escape, and people with their mouths sewn shut for allegedly lying to their captors. In January 2014, the Congolese army officially opened a new phase of military operations against the ADF with some limited logistical support from the UN Stabilization Mission in Congo, MONUSCO, and its “Intervention Brigade,” a 3,000-member force created in mid-2013 to carry out military operations against armed groups. The series of massacres began several months after the Congolese army pushed the ADF out of their main bases.

The UN Group of Experts found that Brig. Gen. Muhindo Akili Mundos, the Congolese army commander responsible for military operations against the ADF from August 2014 to June 2015, had recruited ADF fighters, former fighters from local armed groups known as Mai Mai, and others to establish a new armed group. This group was implicated in some of the massacres in Beni territory that began in October 2014, according to the Group of Experts.

In a March 2016 report, the Congo Research Group found that certain army elements as well as armed groups other than the ADF might be involved in the massacres.

The forces responsible, chains of command, and motivations behind these attacks remain unclear. Congo’s international partners should support credible government efforts to determine responsibility for the attacks and to improve protection for civilians, Human Rights Watch said.

Given the alleged involvement of some Congolese army officers in the massacres, MONUSCO should ensure full respect for the UN Human Rights Due Diligence Policy when supporting Congolese army operations and withhold all support to units or commanders that may be implicated in the attacks or other serious human rights violations. UN peacekeepers should also improve ties with local communities and immediately deploy to threatened areas.

Human Rights Watch urged the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to collect information to determine whether an ICC investigation into alleged crimes in the Beni area is warranted. The ICC opened an investigation in Congo in June 2004, and has jurisdiction over serious international crimes committed on Congolese territory. The ICC can step in when national courts are unwilling or unable to prosecute grave crimes in violation of international law.

The frequent massacres in Beni have fuelled popular anger at the Congolese government for failing to stop the killings, prompting numerous city-wide shutdowns or “villes mortes” (dead cities), peaceful marches, and some incidents of vigilante violence in the east.

Protests against the Beni killings have in some cases been linked to demonstrations against election delays and attempts to extend President Joseph Kabila’s presidency beyond the end of his constitutionally mandated two-term limit, which ends on December 19. In many cases, government officials and security forces have responded to protests with brutal repression.

“With Congo embroiled in a broader political crisis, the government is less capable of keeping the attacks in Beni from spiraling out of control,” Sawyer said. “Sustained, high-level international attention is needed now to help end the killings in Beni and to identify and bring to justice those responsible for the attacks.”

World

AfBD, AU Renew Call for Visa-Free Travel to Boost African Economic Growth

By Adedapo Adesanya

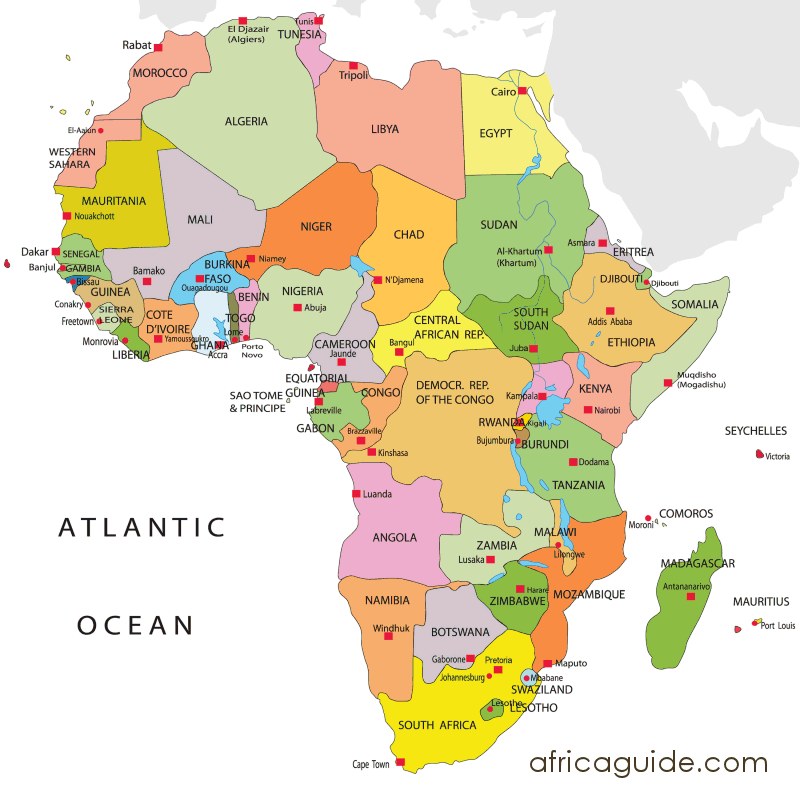

The African Development Bank (AfDB) and the African Union have renewed their push for visa-free travel to accelerate Africa’s economic transformation.

The call was reinforced at a High-Level Symposium on Advancing a Visa-Free Africa for Economic Prosperity, where African policymakers, business leaders, and development institutions examined the need for visa-free travel across the continent.

The consensus described the free movement of people as essential to unlocking Africa’s economic transformation under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The symposium was co-convened by AfDB and the African Union Commission on the margins of the 39th African Union Summit of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa.

The participants framed mobility as the missing link in Africa’s integration agenda, arguing that while tariffs are falling under AfCFTA, restrictive visa regimes continue to limit trade in services, investment flows, tourism, and labour mobility.

On his part, Mr Alex Mubiru, Director General for Eastern Africa at the African Development Bank Group, said that visa-free travel, interoperable digital systems, and integrated markets are practical enablers of enterprise, innovation, and regional value chains to translate policy ambitions into economic activity.

“The evidence is clear. The economics support openness. The human story demands it,” he told participants, urging countries to move from incremental reforms to “transformative change.”

Ms Amma A. Twum-Amoah, Commissioner for Health, Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development at the African Union Commission, called for faster implementation of existing continental frameworks.

She described visa openness as a strategic lever for deepening regional markets and enhancing collective responses to economic and humanitarian crises.

Former AU Commission Chairperson, Ms Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, reiterated that free movement is central to the African Union’s long-term development blueprint, Agenda 2063.

“If we accept that we are Africans, then we must be able to move freely across our continent,” she said, urging member states to operationalise initiatives such as the African Passport and the Free Movement of Persons Protocol.

Ghana’s Trade and Industry Minister, Mrs Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare, shared her country’s experience as an early adopter of open visa policies for African travellers, citing increased business travel, tourism, and investor interest as early dividends of greater openness.

The symposium also reviewed findings from the latest Africa Visa Openness Index, which shows that more than half of intra-African travel still requires visas before departure – seen by participants as a significant drag on intra-continental commerce.

Mr Mesfin Bekele, Chief Executive Officer of Ethiopian Airlines, called for full implementation of the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM), saying aviation connectivity and visa liberalisation must advance together to enable seamless travel.

Regional representatives, including Mr Elias Magosi, Executive Secretary of the Southern Africa Development Community, emphasised the importance of building trust through border management and digital information-sharing systems.

Ms Gabby Otchere Darko, Executive Chairman of the Africa Prosperity Network, urged governments to support the “Make Africa Borderless Now” campaign, while tourism campaigner Ras Mubarak called for more ratifications of the AU Free Movement of Persons protocol.

Participants concluded that achieving a visa-free Africa will require aligning migration policies, digital identity systems, and border infrastructure, alongside sustained political commitment.

World

Nigeria Exploring Economic Potential in South America, Particularly Brazil

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this interview, Uche Uzoigwe, Secretary-General of NIDOA-Brazil, discusses the economic potential in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners for the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN). Follow the discussion here:

How would you assess the economic potential in the South American region, particularly Brazil, for the Federal Republic of Nigeria? What investment incentives does Nigeria have for potential corporate partners from Brazil?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, my response to the questions regarding the economic potentials in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners would be as follows:

Brazil, as the largest economy in South America, presents significant opportunities for the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The country’s diverse economy is characterised by key sectors such as agriculture, mining, energy, and technology. Here are some factors to consider:

- Natural Resources: Brazil is rich in natural resources like iron ore, soybeans, and biofuels, which can be beneficial to Nigeria in terms of trade and resource exchange.

- Growing Agricultural Sector: With a well-established agricultural sector, Brazil offers potential collaboration in agri-tech and food security initiatives, which align with Nigeria’s goals for agricultural development.

- Market Size: Brazil boasts a large consumer market with a growing middle class. This represents opportunities for Nigerian businesses looking to export goods and services to new markets.

- Investment in Infrastructure: Brazil has made significant investments in infrastructure, which could create opportunities for Nigerian firms in construction, engineering, and technology sectors.

- Cultural and Economic Ties: There are historical and cultural ties between Nigeria and Brazil, especially considering the African diaspora in Brazil. This can facilitate easier business partnerships and collaborations.

In terms of investment incentives for potential corporate partners from Brazil, Nigeria offers several attractive incentives for Brazilian corporate partners, including:

- Tax Incentives: Various tax holidays and concessions are available under the Nigerian government’s investment promotion laws, particularly in key sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and technology.

- Repatriation of Profits: Brazil-based companies investing in Nigeria can repatriate profits without restrictions, thus enhancing their financial viability.

- Access to the African Market: Investment in Nigeria allows Brazilian companies to access the broader African market, benefiting from Nigeria’s membership in regional trade agreements such as ECOWAS.

- Free Trade Zones: Nigeria has established free trade zones that offer companies the chance to operate with reduced tariffs and fewer regulatory burdens.

- Support for Innovation: The Nigerian government encourages innovation and technology transfer, making it attractive for Brazilian firms in the tech sector to collaborate, particularly in fintech and agriculture technology.

- Collaborative Ventures: Opportunities exist for joint ventures with local firms, leveraging local knowledge and networks to navigate the business landscape effectively.

In conclusion, fostering a collaborative relationship between Nigeria and Brazil can unlock numerous economic opportunities, leading to mutual growth and development in various sectors. We welcome potential Brazilian investors to explore these opportunities and contribute to our shared economic goals.

In terms of this economic cooperation and trade, what would you say are the current practical achievements, with supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, I would highlight the current practical achievements in economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil, alongside the supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA.

Here are some key points:

Current Practical Achievements

- Increased Bilateral Trade: There has been a notable increase in bilateral trade volume between Nigeria and Brazil, particularly in sectors such as agriculture, textiles, and technology. Recent trade agreements and discussions have facilitated smoother trade relations.

- Joint Ventures and Partnerships: Successful joint ventures have been established between Brazilian and Nigerian companies, particularly in agriculture (e.g., collaboration in soybean production and agricultural technology) and energy (renewables, oil, and gas), demonstrating commitment to mutual development.

- Investment in Infrastructure Development: Brazilian construction firms have been involved in key infrastructure projects in Nigeria, contributing to building roads, bridges, and facilities that enhance connectivity and economic activity.

- Cultural and Educational Exchange Programs: Programs facilitating educational exchange and cultural cooperation have led to strengthened ties. Brazilian universities have partnered with Nigerian institutions to promote knowledge transfer in various fields, including science, technology, and arts.

Supporting Strategies

- Strategic Trade Dialogue: NIDOA has initiated regular dialogues between trade ministries of both nations to discuss trade barriers, potential markets, and cooperative opportunities, ensuring both countries are aligned in their economic goals.

- Investment Promotion Initiatives: Targeted initiatives have been established to promote Brazil as an investment destination for Nigerian businesses and vice versa. This includes showcasing success stories at international trade fairs and business forums.

- Capacity Building and Technical Assistance: NIDOA has offered capacity-building programs focused on enhancing Nigeria’s capabilities in agriculture and technology, leveraging Brazil’s expertise and sustainable practices.

- Policy Advocacy: Continuous advocacy for favourable trade policies has been a key focus for NIDOA, working to reduce tariffs and promote economic reforms that facilitate investment and trade flows.

Systemic Engagement

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Engaging the private sector through PPPs has been essential in mobilising resources for development projects. NIDOA has actively facilitated partnerships that leverage both public and private investments.

- Trade Missions and Business Delegations: Organised trade missions to Brazil for Nigerian businesses and vice versa, allowing for direct engagement with potential partners, fostering trust and opening new channels for trade.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: NIDOA implements a rigorous monitoring and evaluation framework to assess the impact of various initiatives and make necessary adjustments to strategies, ensuring effectiveness in achieving economic cooperation goals.

Through these practical achievements, supporting strategies, and systemic engagement, NIDOA continues to play a pivotal role in enhancing economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil. By fostering collaboration and leveraging shared resources, we aim to create a sustainable and mutually beneficial economic environment that promotes growth for both nations.

Do you think the changing geopolitical situation poses a number of challenges to connecting businesses in the region with Nigeria, and how do you overcome them in the activities of NIDOA?

The changing geopolitical situation indeed poses several challenges for connecting businesses in the South American region, particularly Brazil, with Nigeria. These challenges include trade tensions, shifting alliances, currency fluctuations, and varying regulatory environments. Below, I will outline some of the specific challenges and how NIDOA works to overcome them:

Current Challenges

- No Direct Flights: This challenge is obviously explicit. Once direct flights between Brazil and Nigeria become active, and hopefully this year, a much better understanding and engagement will follow suit.

- Trade Restrictions and Tariffs: Increasing trade protectionism in various regions can lead to higher tariffs and trade barriers that hinder the movement of goods between Brazil and Nigeria.

- Currency Volatility: Fluctuations in the value of currencies can complicate trade agreements, pricing strategies, and overall financial planning for businesses operating in both Brazil and Nigeria.

- Different regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements in both countries can create challenges for businesses aiming to navigate these systems efficiently.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Changes in global supply chains due to geopolitical factors may disrupt established networks, impacting businesses relying on imports and exports between the two nations.

Overcoming Challenges through NIDOA.

NIDOA actively engages in discussions with both the Brazilian and Nigerian governments to advocate for favourable trade policies and agreements that reduce tariffs and improve trade conditions. This year in October, NIDOA BRAZIL holds its TRADE FAIR in São Paulo, Brazil.

What are the popular sentiments among the Nigerians in the South American diaspora? As the Secretary-General of the NIDOA, what are your suggestions relating to assimilation and integration, and of course, future perspectives for the Nigerian diaspora?

As the Secretary-General of NIDOA, I recognise the importance of understanding the sentiments among Nigerians in the South American diaspora, particularly in Brazil.

Many Nigerians in the diaspora take pride in their cultural roots, celebrating their heritage through festivals, music, dance, and culinary traditions. This cultural expression fosters a sense of community and belonging.

While many individuals embrace their new environments, they often face challenges related to cultural differences, language barriers, and social integration, which can lead to feelings of isolation.

Many express optimism about opportunities in education, business, and cultural exchange, viewing their presence in South America as a chance to expand their horizons and contribute to economic activities both locally and back in Nigeria.

Sentiments regarding acceptance vary; while some Nigerians experience warmth and hospitality, others encounter prejudice or discrimination, which can impact their overall experience in the host country. NIDOA BRAZIL has encouraged the formation of community organisations that promote networking, cultural exchange, and social events to foster a sense of belonging and support among Nigerians in the diaspora. There are currently two forums with over a thousand Nigerian members.

Cultural Education and Awareness Programs: NIDOA BRAZIL organises cultural education programs that showcase Nigerian heritage to local communities, promoting mutual understanding and appreciation that can facilitate smoother integration.

Language and Skills Training: NIDOA BRAZIL provides language courses and skills training programs to help Nigerians, especially students in tertiary institutions, adapt to their new environment, enhancing communication and employability within the host country.

Engaging in Entrepreneurship: NIDOA BRAZIL supports the entrepreneurial spirit among Nigerians in the diaspora by facilitating access to resources, mentorship, and networks that can help them start businesses and create economic opportunities.

Through its AMBASSADOR’S CUP COMPETITION, NIDOA Brazil has engaged students of tertiary institutions in Brazil to promote business projects and initiatives that can be implemented in Nigeria.

NIDOA BRAZIL also pushes for increased tourism to Brazil since Brazil is set to become a global tourism leader in 2026, with a projected 10 million international visitors, driven by a post-pandemic rebound, enhanced air connectivity, and targeted marketing strategies.

Brazil’s tourism sector is poised for a remarkable milestone in 2026, as the country expects to welcome over 10 million international visitors—surpassing the previous record of 9.3 million in 2025. This expected surge represents an ambitious leap, nearly doubling the country’s foreign-arrival numbers within just four years, a feat driven by a combination of pent-up global demand, strategic air connectivity improvements, and a highly targeted marketing campaign.

World

African Visual Art is Distinguished by Colour Expression, Dynamic Form—Kalalb

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this insightful interview, Natali Kalalb, founder of NAtali KAlalb Art Gallery, discusses her practical experiences of handling Africa’s contemporary arts, her professional journey into the creative industry and entrepreneurship, and also strategies of building cultural partnership as a foundation for Russian-African bilateral relations. Here are the interview excerpts:

Given your experience working with Africa, particularly in promoting contemporary art, how would you assess its impact on Russian-African relations?

Interestingly, my professional journey in Africa began with the work “Afroprima.” It depicted a dark-skinned ballerina, combining African dance and the Russian academic ballet tradition. This painting became a symbol of cultural synthesis—not opposition, but dialogue.

Contemporary African art is rapidly strengthening its place in the world. By 2017, the market was growing so rapidly that Sotheby launched its first separate African auction, bringing together 100 lots from 60 artists from 14 foreign countries, including Algeria, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, and others. That same year during the Autumn season, Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris hosted a major exhibition dedicated to African art. According to Artnet, sales of contemporary African artists reached $40 million by 2021, a 434% increase in just two years. Today, Sotheby holds African auctions twice a year, and in October 2023, they raised $2.8 million.

In Russia, this process manifests itself through cultural dialogue: exhibitions, studios, and educational initiatives create a space of trust and mutual respect, shaping the understanding of contemporary African art at the local level.

Do you think geopolitical changes are affecting your professional work? What prompted you to create an African art studio?

The international context certainly influences cultural processes. However, my decision to work with African themes was not situational. I was drawn to the expressiveness of African visual language—colour, rhythm, and plastic energy. This theme is practically not represented systematically and professionally in the Russian art scene.

The creation of the studio was a step toward establishing a sustainable platform for cultural exchange and artistic dialogue, where the works of African artists are perceived as a full-fledged part of the global cultural process, rather than an exotic one.

To what extent does African art influence Russian perceptions?

Contemporary African art is gradually changing the perception of the continent. While previously viewed superficially or stereotypically, today viewers are confronted with the depth of artistic expression and the intellectual and aesthetic level of contemporary artists.

Portraits are particularly impactful: they allow us to see not just an abstract image of a “continent,” but a concrete personality, character, and inner dignity. Global market growth data and regular auctions create additional trust in African contemporary art and contribute to its perception as a mature and valuable movement.

Does African art reflect lifestyle and fashion? How does it differ from Russian art?

African art, in my opinion, is at its peak in everyday culture—textiles, ornamentation, bodily movement, rhythm. It interacts organically with fashion, music, interior design, and the urban environment. The Russian artistic tradition is historically more academic and philosophical. African visual art is distinguished by greater colour expression and dynamic form. Nevertheless, both cultures are united by a profound symbolic and spiritual component.

What feedback do you receive on social media?

Audience reactions are generally constructive and engaging. Viewers ask questions about cultural codes, symbolism, and the choice of subjects. The digital environment allows for a diversity of opinions, but a conscious interest and a willingness to engage in cultural dialogue are emerging.

What are the key challenges and achievements of recent years?

Key challenges:

- Limited expert base on African contemporary art in Russia;

- Need for systematic educational outreach;

- Overcoming the perception of African art as exclusively decorative or ethnic.

Key achievements:

- Building a sustainable audience;

- Implementing exhibition and studio projects;

- Strengthening professional cultural interaction and trust in African

contemporary art as a serious artistic movement.

What are your future prospects in the context of cultural diplomacy?

Looking forward, I see the development of joint exhibitions, educational programs, and creative residencies. Cultural diplomacy is a long-term process based on respect and professionalism. If an artistic image is capable of uniting different cultural traditions in a single visual space, it becomes a tool for mutual understanding.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn