Economy

Crude Oil Prices Fall To Lowest Levels in 10 Months

By Adedapo Adesanya

The prices of the crude oil grades in the market fell to their lowest levels this year on Wednesday, losing all of the gains they had accumulated since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Brent futures fell by $2.18 or 2.8 per cent to trade at $77.17 a barrel, as the United States West Texas Intermediate (WTI) futures depreciated by $2.24 to $72.01 per barrel.

Oil surged to nearly $140 a barrel in March, close to an all-time record, following the launch of what Russia tagged a “special operation” in Ukraine a month earlier.

The market has been steadily declining recently as economists brace for weakened worldwide growth in part due to high energy costs.

The situation worsened on Wednesday with bigger-than-expected increases in US fuel inventories despite a drop in crude stocks.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported an inventory decline of 5.2 million barrels for the week of December 2 compared with a sizeable draw of 12.6 million barrels estimated for the previous week, which sent prices higher at the time.

A day before the EIA released its report, the American Petroleum Institute estimated another weekly crude inventory draw for the week to December 2 at 6.43 million barrels.

Meanwhile, the EIA also reported an inventory build in fuel and another rise in middle distillate stocks for the week to December 2. Gasoline (petrol) inventories added 5.3 barrels in the week to December 2, with production averaging 9.1 million barrels daily, in contrast to a build of 2.8 million barrels for the previous week and a production rate of 9.4 million barrels daily.

Prices are also slipping further down as traders relax about the potential consequences of the G7 and EU price cap on Russian oil.

It appears they have assumed that it would not affect the availability of oil in any significant way and are selling crude.

Analysts also note that Russian oil is already trading close to the cap, so it shouldn’t make much of a difference in revenues, but it is worth remembering Russia has said it would not sell oil to countries that enforce the price cap, meaning the supply of Russian oil specifically might tighten for some importers.

Russia has also threatened to set a price floor for its oil in response to the G7 price cap, which may further complicate matters.

Support came as China, the world’s biggest crude importer, announced the most sweeping changes to its anti-COVID regime since the pandemic began. The country’s crude oil imports in November rose 12 per cent from a year earlier to their highest in 10 months, data showed.

Still, warnings from big US banks about a likely recession next year weighed on the value of the commodity.

Economy

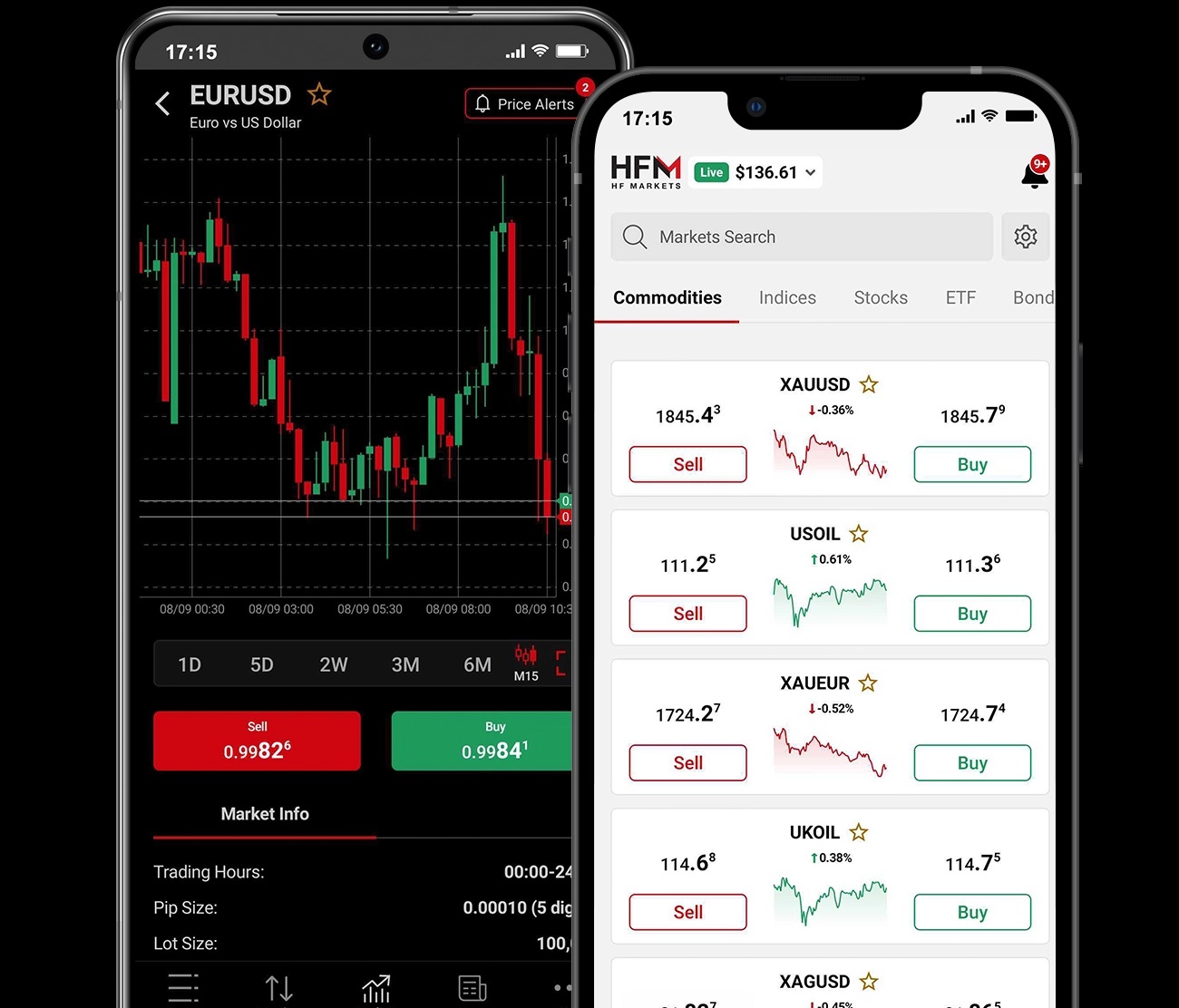

Why Transparency Matters in Your Choice of a Financial Broker

Choosing a Forex broker is essentially picking a partner to hold the wallet. In 2026, the market is flooded with flashy ads promising massive leverage and “zero fees,” but most of that is just noise. Real transparency is becoming a rare commodity. It isn’t just a corporate buzzword; it’s the only way a trader can be sure they aren’t playing against a stacked deck. If a broker’s operations are a black box, the trader is flying blind, which is a guaranteed way to blow an account.

The Scam of “Zero Commissions”

The first place transparency falls apart is in the pricing. Many brokers scream about “zero commissions” to get people through the door, but they aren’t running a charity. If they aren’t charging a flat fee, they are almost certainly hiding their profit in bloated spreads or “slippage.” A trader might hit buy at one price and get filled at a significantly worse one without any explanation. This acts as a silent tax on every trade. A transparent broker doesn’t hide the bill; they provide a live, auditable breakdown of costs so the trader can actually calculate their edge.

The Conflict of Market Making

It is vital to know who is on the other side of the screen. Many brokers act as “Market Makers,” which is a polite way of saying they win when the trader loses. This creates a massive conflict of interest. There is little incentive for a broker to provide fast execution if a client’s profit hurts their own bottom line. A broker with nothing to hide is open about using an ECN or STP model, simply passing orders to the big banks and taking a small, visible fee. If a broker refuses to disclose their execution model, they are likely betting against their own clients.

Regulation as a Safety Net

Transparency is worthless without an actual watchdog. A broker that values its reputation leads with its licenses from heavy-hitters like the FCA or ASIC. They don’t bury their regulatory status in the fine print or hide behind “offshore” jurisdictions with zero oversight. More importantly, they provide proof that client funds are kept in segregated accounts. This ensures that if the broker goes bust, the money doesn’t go to their creditors—it stays with the trader. Without this level of openness, capital is essentially unprotected.

The Withdrawal Litmus Test

The ultimate test of a broker’s transparency is how they handle the exit. There are countless horror stories of traders growing an account only to find that “technical errors” or vague “bonus terms” prevent them from withdrawing their money. A legitimate broker has clear, public rules for getting funds out and doesn’t hide behind a wall of unreturned emails. If a platform makes it difficult to see the exit strategy, it’s a sign that the front door should have stayed closed.

Conclusion

In 2026, honesty is the most valuable feature a broker can offer. It is the foundation that allows a trader to focus on the charts instead of worrying if their stops are being hunted. Finding a partner with clear pricing, honest execution, and real regulation is the first trade that has to be won. Flashy marketing is easy to find, but transparency is what actually keeps a trader in the game for the long haul.

Economy

Nigeria’s Stock Market Indices Shrink 0.41% Amid Panic Sell-Offs

By Dipo Olowookere

The Nigerian Exchange (NGX) Limited came under panic sell-offs on Thursday, as the investing community awaits the outcome of a probe into trading activities around one of the stocks on the bourse.

On Monday, trading in Zichis equities was prohibited by the regulator after it gained almost 900 per cent in one month of being listed by introduction on the growth board of the exchange.

This action triggered cautious trading on Customs Street, and things have not remained the same since then.

Yesterday, the key performance indices of the Nigerian bourse further depreciated by 0.41 per cent, the third straight loss this week, as investors book profit before being trapped.

It was observed that the energy industry gained 0.12 per cent and was the only one in green, as the industrial goods space shed 1.19 per cent, the banking counter depreciated by 0.63 per cent, the insurance sector lost 0.32 per cent, and the consumer goods segment tumbled by 0.03 per cent.

As a result, the All-Share Index (ASI) contracted by 802.39 points to 193,567.81 points from 194,370.20 points, and the market capitalisation decreased by N515 billion to N124.239 trillion from N124.754 trillion.

During the session, investors traded 868.5 million shares worth N31.5 billion in 69,310 deals compared with the 1.4 billion shares valued at N46.2 billion exchanged in 70,222 deals at midweek, showing a drop in the trading volume, value, and number of deals by 37.96 per cent, 31.82 per cent, and 1.30 per cent, respectively.

Jaiz Bank led the activity chart with 78.9 million equities valued at N1.2 billion, Japaul traded 73.3 million stocks worth N274.8 million, Access Holdings exchanged 66.9 million shares for N1.7 billion, Chams sold 56.9 million equities worth N239.6 million, and Zenith Bank transacted 45.5 million stocks valued at N4.1 billion.

The worst-performing stock for the day was Jaiz Bank after it lost 9.98 per cent to trade at N12.63, Ikeja Hotel declined by 9.90 per cent to N37.75, John Holt shrank by 9.90 per cent to N8.65, Enamelware slipped by 9.88 per cent to N36.50, and Cadbury went down by 9.69 per cent to N61.95.

On the flip side, FTN Cocoa was the best-performing stock after it gained 10.00 per cent to sell for N6.05, RT Briscoe improved by 9.95 per cent to N11.38, Deap Capital soared 9.92 per cent to N6.98, Japaul grew by 9.91 per cent to N3.77, and Ellah Lakes surged 9.72 per cent to N11.85.

Investor sentiment remained bearish as the exchange finished with 30 price gainers and 38 price losers, implying a negative market breadth index.

Economy

Champion Breweries Concludes Bullet Brand Portfolio Acquisition

By Aduragbemi Omiyale

The acquisition of the Bullet brand portfolio from Sun Mark has been completed by Champion Breweries Plc, a statement from the company confirms.

This marks a transformative milestone in the organisation’s strategic expansion into a diversified, pan-African beverage platform.

With this development, Champion Breweries now owns the Bullet brand assets, trademarks, formulations, and commercial rights globally through an asset carve-out structure.

The assets are held in a newly incorporated entity in the Netherlands, in which Champion Breweries holds a majority interest, while Vinar N.V., the majority shareholder of Sun Mark, retains a minority stake.

Bullet products are currently distributed in 14 African markets, positioning Champion Breweries to scale beyond Nigeria in the high-growth ready-to-drink (RTD) alcoholic and energy drink segments.

This expansion significantly broadens the brewer’s addressable market and strengthens its revenue base with an established, profitable portfolio that already enjoys strong brand recognition and consumer loyalty across multiple markets.

“The successful completion of our public equity raises, together with the formal close of the Bullet acquisition, marks a defining moment for Champion Breweries.

“The support we received from both existing shareholders and new investors reflects strong confidence in our long-term strategy to build a diversified, high-growth beverage platform with pan-African scale.

“Our focus now is on disciplined execution, integration, and delivering sustained value across markets,” the chairman of Champion Breweries, Mr Imo-Abasi Jacob, stated.

Through this transaction, Champion Breweries is expected to achieve enhanced foreign exchange earnings, expanded distribution leverage across African markets, integrated supply chain efficiencies, portfolio diversification into high‑growth consumer beverage categories, and strengthened presence in the RTD and energy drink segments.

The acquisition accelerates Champion Breweries’ transition from a regional brewing business to a multi-category consumer platform with continental reach.

Bullet Black is Nigeria’s leading ready-to-drink alcoholic beverage, while Bullet Blue has built a strong presence in the energy drink category across several African markets.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn