Feature/OPED

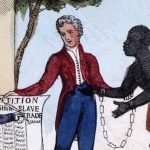

2023 Power Shift: A Greek Gift? (Part 1)

By Christie Obiaruko Ndukwe

The airwaves have been inundated with the call for a power shift from the North to the South even though zoning and rotation are not expressly provided for in the 1999 Constitution handed down to us by the Military under Gen Abdulsaalam Abubakar rtd.

It is an internal arrangement by political parties aimed at balancing power and stemming the crisis that may arise if a particular people continue to hold on to power.

Since the return to democracy uninterrupted in 1999, this arrangement has received some sort of stability at the Centre and in most states. While we have practised the North-South rotation, the dynamics are shifting to the six geopolitical zones with the North and South having three zones each.

The rotation along the zones seems to be threatened towards the build-up to the 2023 general elections. The South is where the battle will be fought and the victory will be in the North.

The silence of the Nigerian Constitution, as well as the Electoral Act as amended, is the catalyst for the coming implosion in the South as some political gladiators from the South West and by extension, the South-South are already throwing their hats into the ring.

The South East which is the only zone in the South to have clinched the top job, ordinarily in the spirit of Equity and Fairplay is facing an impending self-destruct with the ideals of the apex Igbo Socio-cultural organisation, Ohaneze Ndigbo being weighed on a moral scale.

The group believes that the Igbo people are also found in other states other than the South East, thereby making it difficult to deny their kith and kin from Rivers, Delta, Benue, Bayelsa, Cross River and Akwa Ibom the right to contest for the Presidency in 2023.

It is gradually becoming an individual race as more persons indicate interest to run. Those who insist on the Zonal arrangement have also forgotten that the North with two opportunities – late Musa Yar’Adua and Muhammadu Buhari have failed to transit from one zone to another. The two hail from the same State and Zone. It is even more interesting than they are both from the same tribe-Fulani.

The unfortunate ill-health of President Umaru Yar’adua threw up the highly debated Doctrine of Necessity which had Goodluck Jonathan his Deputy step in as the Acting President and subsequently, President when Yar’Adua eventually died. He had barely spent only two years in office and a constitutional crisis erupted.

It was not shocking to many as rumour of his ill-health was rife even before he was inaugurated as President. I recall the funny but unfortunate incident during one of the Presidential campaigns where the then President, Olusegun Obasanjo made a call to the ailing candidate of the PDP asking if he was dead or alive. In his usual humorous way, Obasanjo asked Yaradua who was hospitalised after collapsing at a Presidential rally if he could confirm or refute the rumour that he was dead.

Yes, Yar’Adua was not dead at that time but he was sick and very sick. It was common knowledge in and around Katsina State where he was Governor for eight years that he could not have fully discharged his role as the Chief Executive due to his ailment. It was not about his age though certain ailments are triggered by old age. It’s a natural occurrence.

The unfortunate crisis created by President Obasanjo who many believe knew the state of Yar’Adua’s health vis-à-vis eventually altered the zoning pattern with the South-South replacing the North West for a period of six years. This new order paved the way for a South to hold sway for fourteen years. Obasanjo from the South West and Jonathan from the South-South spent eight and six years respectively while Late Yar’Adua spent two years and Buhari from the same North West will be spending eight years, totalling ten years for the North West.

There are different pressure groups that have cited different reasons why power should shift either to the South or be retained in the North. The arguments are right depending on the perspective it is viewed from and whose interest it aims at serving.

For the Nigerian people, what matters is balance in structure, security and a stable economy. Beyond the clamour for power shift, there is an earnest camouflaged desire for a leadership shift in real terms and as exemplified by other nations who have conquered religion and ethnicity. An Obama wouldn’t have been if it were in Nigeria!

The reason why the agitation for a shift in where power resides is borne out of the precarious situation where appointments are lopsided in the Federal Civil Service as well as the deliberate marginalisation of a group of people. But then, should good leadership be sacrificed on the altar of zoning and rotation?

The nature of the Nigerian political system where the winner takes all create an even more difficult situation as only those who seem to have been very much around the corridors of power are opportune to vie for these positions albeit tested and not trusted.

The present state of the nation calls for a true National Conference to chart the way forward. But the noise coming from different political camps has consumed any reasonable voice of truth.

The Banditry, Boko Haram, Kidnapping and ritual murders amongst others are issues that must be addressed or else, these monsters will consume the nation in less than no time.

When a similar scenario played out in the Niger Delta region, it was President Umaru Yar’Adua who instituted the Amnesty Program which brought lasting peace in the region. Unfortunately, his good intentions were cut short by death, barely two years after he was elected into office.

It is rather worrying that as the nation grapples with a similar challenge though heightened, the temptation to hand over a sick nation to the South by the North is not being resisted.

The major issues facing Northern Nigeria are unfortunately the creation of the North- Banditry, Boko Haram and kidnapping. If the tide is not stemmed under a President from the North, with most Service Chiefs and heads of security from the same region, is it likely that a Southerner, especially a Christian would be empowered to clean up the Augean stable?

Can the nation survive another four or eight years of a relatively old President with rumours of manageable health?

Without being pretentious, I make bold to say that the secret plot to field those above the age of sixty years to succeed Buhari could be a reenactment of the challenges we have faced under a Buhari Presidency. To be categorical, Bola Ahmed Tinubu has no moral grounds to seek to succeed Buhari considering his age, mental and physical status.

I smell a rat. The Northerners who have joined the campaign are doing so out of a selfish purpose. They want power retained in the North just the way Jonathan continued after Yar’Adua, giving the South an edge over the North.

Also, the joker in the political game is the call for President Jonathan to seek reelection for a period of just four years. That will guarantee the North another eight straight years from 2027!

Either way, it is opportunistic.

The South must reject whatever Greek Gift being offered by the North.

Obiaruko Christie Ndukwe is a socio-political commentator, analyst and columnist based in Port Harcourt, Rivers State

Feature/OPED

$214Bn Missing, Institutions Silent: Is Accountability Dead in Nigeria?

By Blaise Udunze

Between 2010 and 2026, a staggering $214 billion, approximately N300 trillion in public funds, has been reported as missing, unaccounted for, diverted, unrecovered, irregularly spent, or trapped in non-transparent fiscal structures across Nigeria’s public institutions.

That figure is not speculative but a conservative estimate of unaccounted funds. It is drawn from audit reports, legislative probes, civil society litigation, executive directives, and investigative findings spanning more than a decade. If it is to go by the accurate figure, the true national loss is likely higher but difficult to quantify precisely due to data gaps, overlapping figures, and incomplete audits.

The challenge is that in many of the most prominent cases, prosecutions have stalled, hearings have dragged without resolution, investigations have gone cold, and no defining jail terms have etched accountability into Nigeria’s institutional memory. The irony is that the number is historic, the silence is louder. And the economic damage is cumulative.

The pattern stretches from the oil sector to social investment programmes, from the Nigeria Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) interventions to ministry-level expenditures. In 2014, between $10.8 billion and $20 billion in unremitted oil revenues linked to the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation triggered national outrage. Under the then CBN governor, Lamido Sanusi, who warned that persistent oil revenue leakages were making exchange rate stability “extremely difficult.” He cautioned that without full remittances, the alternative would be currency devaluation and financial instability. This concern spans the 2010 to 2013 oil revenue period. That warning proved prophetic.

This is because, years later, the lack of transparency in the oil industry did not disappear, but rather it festered like cancer. It further led to the elongated audit queries, which have continued to trail the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited, including unremitted revenues, questioned deductions, and management fee structures under the Petroleum Industry Act. With an extraordinary move aimed at blocking revenue leakages at source, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has recently issued an Executive Order suspending certain deductions and directing direct remittance of taxes, royalties, and profit oil into the Federation Account, which involves the reassessment of NNPC’s 30 per cent management fee and 30 per cent frontier exploration deduction under the Petroleum Industry Act.

Such presidential intervention underscores the scale of concern, which means that Nigeria cannot afford a structural lack of transparency in its most strategic revenue sector. But oil is only one chapter.

The Central Bank of Nigeria has faced some of the most far-reaching audit alarms in recent years. In suit number FHC/ABJ/CS/250/2026, the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) is asking the Federal High Court to compel the CBN to account for N3 trillion in allegedly missing or diverted public funds. The Auditor-General’s 2025 report cited failures to remit over N1.44 trillion in operating surplus to the Consolidated Revenue Fund, over N629 billion paid to “unknown beneficiaries” under the Anchor Borrowers’ Programme, and more than N784 billion in overdue, unrecovered intervention loans.

There were also N125 billion in questioned intervention expenditures, irregular contract variations exceeding N9 billion, and procurement gaps running into hundreds of billions. The Auditor-General repeatedly recommended recovery and remittance. No date has been fixed for the hearing. Meanwhile, Nigeria continues to borrow.

Elsewhere, the House of Representatives has launched a probe into over N30 billion recovered during investigations into the National Social Investment Programme Agency (NSIPA). The funds, reportedly frozen during investigation, have not been remitted back into the Treasury Single Account, stalling poverty-alleviation schemes like TraderMoni and FarmerMoni. Millions of vulnerable Nigerians remain exposed while lawmakers search for money already “recovered.” The irony is staggering as funds are found, but programmes remain frozen.

A top discovery recently that put the nation on red alert was made by the Senate committee, which claimed to have found N210 trillion in financial irregularities in NNPC accounts between 2017 and 2023, including unaccounted receivables and accrued expenses. A critical concern is that, as of early 2026, this has sparked commentary but no clear prosecutions.

Only recently, in the power sector, SERAP has urged the President to probe alleged missing or unaccounted N128 billion at the Federal Ministry of Power and the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading Plc. Of concern is that despite the enormous funds channelled in this sector, Nigeria’s chronic electricity instability persists, even as billions meant to stabilise the grid face audit scrutiny.

Across MDAs, audit reports between 2017 and 2022 flagged trillions in unsupported expenditures, unremitted taxes, unauthorised payments, and statutory liabilities never recovered. These sums are dizzying and are also alarming; N300 billion here, N149 billion there, N3.403 trillion across agencies, N30 trillion-plus Treasury discrepancies raised at the Senate level.

Individually, they shock. Collectively, they define a structural pattern. And patterns shape economies.

Nigeria operates with structural fiscal deficits and also lives with them routinely and comfortably. Expenditure persistently exceeds revenue. When public funds disappear, fail to be remitted, or are trapped outside constitutional channels, the deficit widens. The government must borrow to fill gaps created not only by low revenue, but by revenue leakage.

Debt servicing now consumes a disproportionate share of federal revenue. Borrowing meant for capital projects increasingly finances recurrent obligations. The country shifts from borrowing to build to borrowing to survive. Every missing naira compounds tomorrow’s liability.

The Treasury Single Account (TSA) was designed to plug such leakages. It consolidated government revenues under Section 80 of the Constitution into a unified framework. International financial institutions commended it as a landmark reform. Yet even today, the Minister of Finance, Wale Edun, has admitted that substantial government funds remain outside the TSA and outside the CBN’s consolidated visibility. Until August 1, 2024, he revealed, the federal government could not fully see its own balance sheet at the apex bank. That admission should alarm any serious economy.

Fiscal lack of transparency constrains planning. It undermines monetary coordination. It weakens debt sustainability projections. It distorts policy responses. And when systems are in flux, money vanishes more easily.

Changing or weakening the TSA in such an environment would be catastrophic. Transitions create windows of vulnerability. Old accounts close. New accounts open. Reconciliation’s lag. Ghost contractors reappear. Double payments slip through.

Albeit, the government must learn to tread with caution as Nigeria’s institutional bandwidth is already strained by simultaneous tax reforms, exchange-rate adjustments, subsidy removal, and fiscal restructuring. One truth that cannot be argued is that layering additional structural upheaval onto fragile systems risks revenue loss that the country cannot afford. Investors are watching.

Credit markets evaluate not just numbers but institutional consistency. A nation that abandons or weakens its most credible fiscal reform sends a destabilising signal. Stability lowers borrowing costs. Institutional drift raises them. But beyond markets lies the human cost.

N300 trillion represents roads not built, power plants not completed, irrigation systems not funded, schools not modernised, and hospitals not equipped. It represents jobs not created and industries not catalysed. It represents stalled productivity and deferred growth.

When intervention loans remain unrecovered, agricultural output suffers. When power sector funds are unaccounted for, electricity remains unstable. When social investment funds are frozen, poverty deepens.

Inflation then compounds the pain. Revenue gaps push borrowing. Borrowing pressures, interest rates and by extension, liquidity misalignment fuel price instability. Citizens pay through higher food costs, transport fares, and rent. The poor pay first. The middle class erodes quietly.

Perhaps most corrosive is the trust deficit. When audit queries fade without visible accountability, tax morale weakens. Compliance declines. Cynicism hardens. A nation cannot modernise where trust in fiscal integrity is fragile.

Section 15(5) of the Constitution requires the abolition of corrupt practices. Financial Regulations mandate a surcharge and referral to anti-corruption agencies where public officers fail to account for funds. The Fiscal Responsibility Act empowers citizens to enforce compliance to ensure that government officials follow fiscal rules. But enforcement defines seriousness.

Nigeria’s problem is not a lack of audit findings. It is the distance between findings and finality.

Nations do not collapse overnight due to a lack of funds. They drift. Infrastructure decays incrementally. Debt rises gradually. Growth slows subtly. Confidence erodes quietly. Then one day, stagnation feels permanent. $214 billion (N300 trillion), sixteen years of recurring audit alarms. Few conclusive accountability outcomes are proportionate to the scale. Truly, the consequences have been less strong. For the same reason, the country witnessed President Tinubu nominating ex-NIA boss Ayodele Oke as ambassador despite a $43 million loot in an Ikoyi apartment.

See the research breakdown of some of the audit figures that reveal staggering sums as enumerated above:

– $10.8 billion and separately $20 billion in unaccounted oil revenues at the NNPC in 2014

– $1.1 billion controversial Malabu Oil and Gas oil deal in 2015

– $2.2 billion arms procurement irregularities in 2015

– N3.4 billion from IMF COVID-19 financing flagged in a 2020 audit.

– N149.36 billion, N37.2 billion, and multiple irregular MDA expenditures in 2020 alone.

– N300 billion cited in public audit concerns in 2017.

– N210 trillion in financial irregularities uncovered, N103 trillion in ‘accrued expenses’, and another N107 trillion in unaccounted ‘receivables’ (2017 -2023).

– N57 billion Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs – (2021)

– N3 trillion and N1.44 trillion flagged in 2022 audit issues involving the Central Bank of Nigeria.

– Nearly N630 billion under the Anchor Borrowers Programme is reportedly unrecovered.

– N784 billion in overdue intervention loans flagged.

– Over N3.403 trillion unaccounted for across federal MDAs between 2019 and 2021.

– Roughly 30 trillion+ in Treasury Single Account and Consolidated Revenue Fund discrepancies raised at the Senate level.

– N500 billion in unremitted oil revenues between 2019 and 2024.

– N80 billion tied to alleged fictitious contracts in the Accountant-General’s office.

– N69.9 billion in uncollected statutory tax liabilities.

– Billions more in unauthorised or undocumented expenditures across ministries.

The institutions differ. The years differ. The audit language differs. The pattern does not.

Nigeria’s economic future will not be determined solely by how much oil it produces, how many reforms it announces, or how many executive orders it signs. It will be determined by whether every naira earned enters the Federation Account transparently, whether every intervention loan is tracked and recovered, whether every surplus is remitted constitutionally, and whether every diversion carries consequences. Revenue generation matters. Revenue protection is destiny. Because when government funds go missing, nations do not stand still. They move backwards.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

Feature/OPED

The Hidden Workforce of the 2026 Access Bank Lagos City Marathon

When the final runner crossed the finish line at the 11th edition of the Access Bank Lagos City Marathon (ABLCM), the applause began to fade. But for hundreds of workers across Lagos, the real work was just beginning.

Major highways had been closed to facilitate the event. Tens of thousands of runners moved through the city in a coordinated surge of athletic endurance. Thousands of bottles of water and energy drinks were distributed, alongside sachets containing essential medical supplies and medication. The race route itself was meticulously prepared, lined with banners, barricades, medical tents and precision timing systems that ensured safety, organisation and accurate performance tracking from start to finish.

What followed was the part that a few cameras lingered on, yet it remains one of the clearest indicators of institutional progress.

Within minutes of the race conclusion, coordinated sanitation teams fanned out across the marathon corridor. Their work went beyond sweeping. Waste was systematically sorted. Plastic bottles were separated from general refuse. Sachets were gathered in bulk. Collection trucks moved along predefined routes, ensuring rapid evacuation of waste. Temporary race infrastructure was dismantled with quiet precision.

In a megacity like Lagos, speed is a necessity. Urban momentum cannot pause for long. The ability to restore order quickly after an event of this magnitude reflects operational discipline across interconnected systems, municipal authorities, environmental agencies, private waste management partners and event coordinators.

Globally, large-scale sporting events are no longer evaluated solely by participation numbers or prize purses. Sustainability has emerged as a defining metric. Environmental responsiveness is now a core measure of credibility. Cities seeking tourism growth, foreign investment and international partnerships must demonstrate that scale does not compromise responsibility. The 2026 marathon provided a compelling case study in this evolution.

The clean-up operation itself generated meaningful economic activity. Temporary employment opportunities emerged for sanitation workers and logistics personnel. Recycling partners engaged in material recovery, reinforcing circular economy value chains. What was once viewed as routine waste disposal has evolved into a structured ecosystem of environmental services, a sector of increasing importance in modern urban economies.

This level of sustainability was the result of deliberate planning. Effective post-event recovery requires route mapping, waste volume projections, coordination between sponsors such as Access Bank Plc and municipal bodies, contingency planning for congestion points and clear communication protocols.

Each edition of the marathon has built on lessons from the last. International participation has expanded. Accreditation standards have strengthened. Media visibility has grown. Most importantly, environmental management has become embedded in the marathon’s operational framework rather than treated as an afterthought.

Progress rarely arrives in dramatic leaps, it advances through incremental improvements, refined systems and institutional learning. Just as elite runners close performance gaps through disciplined training, cities strengthen their global standing through consistent operational excellence.

The 2026 marathon, therefore, tells a story that extends far beyond athletic achievement. It is a story of coordination, sustainability as strategy rather than slogan, and the often unseen workforce, sanitation workers, planners, volunteers, security officials and environmental partners, whose discipline sustains the spectacle.

Because in the end, global cities are judged by how well they host and how responsibly they restore. On the marathon day in Lagos, it was the runners who demonstrated endurance and the systems, and the people behind them, who ensured that when the cheering stopped, the city kept moving.

Feature/OPED

N328.5bn Billing: How Political Patronage Built Lagos’ Agbero Shadow Tax Empire

By Blaise Udunze

Lagos prides itself as Africa’s commercial nerve centre. It markets innovation, fintech unicorns, rail lines, blue-water ferries, and billion-dollar real estate. Though with the glittering skyline and megacity ambition lies a parallel state, a shadow taxation regime run not from Alausa, but from motor parks, bus stops, and highway shoulders. They are called “agberos.” And for decades, they have functioned as Lagos’ unofficial tax masters.

What began as loosely organised transport unionism mutated into a pervasive and often violent system of extortion. Today, tens of thousands of commercial buses, over 75,000 danfos according to estimates by the Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority, ply Lagos roads daily. Each bus is a moving ATM. Each stop is a tollgate. Each route is a revenue corridor.

Looking at the daily estimate from their operations, at N7,000 to N12,000 per bus per day, conservative calculations show that between N525 million and N900 million is extracted daily from drivers. Annually, that balloons toward N192 billion to N328.5 billion or more, money collected in cash, unreceipted, unaudited, unaccounted for. This illicit taxation on an industrial scale did not emerge in a vacuum.

The reality today is that to understand the scale of the problem, one must confront its political history. It was during the administration of Bola Ahmed Tinubu as Lagos State governor from 1999 to 2007, who is now the President, that the entrenchment of transport union dominance and motor park patronage deepened.

Under his political machine, transport unions became not just labour associations but mobilisation structures, formidable grassroots networks capable of crowd control, voter turnout engineering, and territorial enforcement. In exchange for political loyalty, street influence translated into operational latitude.

Motor parks became power bases. “Area boys” became enforcers. Union leadership became politically connected. What should have been regulated associations morphed into revenue-generating franchises with muscle.

The system outlived his tenure. It institutionalised itself. It professionalised. It is embedded in Lagos’ political economy.

And today, it thrives in broad daylight. Endeavour to visit Ajah under bridge, Ikeja under bridge, or Mile-2 along Ojo at 6:00 a.m. Watch drivers clutching crumpled naira notes. Observe men in green trousers and caps marked NURTW weaving between buses, collecting what drivers call òwò àrò, or evening as òwò iròlè money taken from passengers.

A korope driver shouts, “Berger straight!” His bus fills. The engines rumble. But before he moves, he must pay. If he refuses? The side mirror may disappear. The windscreen may crack. The conductor may be assaulted. The vehicle may be blocked with planks, and if they resist, the conductor or driver may be beaten. Movement becomes impossible. It is not optional.

This is common across Lagos, especially amongst drivers in Oshodi, Obalende, Ojodu Berger, Mile 2, Iyana Iba, and Badagry, and describes a three-layered structure ranging from street collectors, area coordinators, and union executives at each location. Daily targets flow upward. Commissions remain below.

One conductor disclosed he budgets at N8,500 daily for louts alone, excluding fuel, delivery to vehicle owners, and official tickets. Another driver says he parts with nearly N15,000 in total daily levies across routes.

Of N40,000 collected on trips, barely N22,000 survives before fuel. Sometimes, drivers go home with N3,500. Working like elephants. Eating like ants. The impact extends far beyond drivers.

Every naira extorted is transferred to commuters. An N700 fare becomes N1,500. A N400 corridor becomes N1,200 in traffic, and this is maintained even after fuel prices fall; fares rarely decline. The hidden levy remains.

Retail traders reduce stock purchases because transport eats profits. Civil servants watch salaries stagnate while commuting costs climb. Market women complain that surviving Lagos costs more than living in it.

This is not just a transport disorder. It is inflation engineered by coercion. Economists call it financial leakage, money extracted from the productive economy that never enters the fiscal system. Billions circulate annually without appearing in government ledgers. No roads are built from it. No hospitals funded. No schools renovated.

It is taxation without development. Small and Medium Enterprises form nearly half of Nigeria’s GDP and employ the majority of its workforce. In Lagos, they are under assault from informal levies layered on top of official taxes. Goods delivered by bus carry hidden transport premiums. Commuting staff face higher daily costs. Inflation ripples through supply chains.

The strike by commercial drivers in 2022 exposed the depth of resentment. Under the Joint Drivers’ Welfare Association of Nigeria (JDWAN), drivers protested “unfettered and violent extortion.” Lagos stood still. Commuters trekked. Appointments were missed. Businesses stalled.

Drivers alleged that half of their daily income vanished into motor park collections.

Some who protested were attacked. Yet the collections continued.

Drivers insist daily collections at single corridors can exceed N5 million. Park chairmen allegedly control enormous cash flows. Uniformed collectors operate with visible confidence.

Meanwhile, the Lagos State Government denies sanctioning any roadside extortion. Officials describe the tax system as institutionalised and structured. They promise reforms through Bus Rapid Transit, rail expansion and corridor standardisation. Yet the shadow toll persists.

Contrast this with Enugu State, where Governor Peter Mbah introduced a Unified e-Ticket Scheme mandating digital payments directly into the state treasury. Paper tickets were banned. Cash collections outlawed. Revenue flows are traceable. Harassment criminalised.

Drivers in Lagos say openly that they should be given a single N5,000 daily ticket paid directly to the government, and end the chaos. Instead, they face multiple actors, agberos, task forces, and traffic officials, each demanding settlement.

The difference is in governance philosophy. One digitises and centralises revenue to eliminate leakages.

The other tolerates fragmentation that breeds shadow collectors. The uncomfortable truth is that the agbero structure is politically sensitive. Transport unions are not just labour bodies; they are political instruments. They mobilise during elections. They maintain territorial presence. They command street loyalty. In return, they are allegedly tolerated, protected, or absorbed into broader political structures as they turn into war instruments and a battle axe in the hands of the government of the day. The underlying reality is that the agbero who are the street-level power structures and the government authorities benefit from each other; the line between unofficial influence and official governance becomes unclear, making reform politically sensitive.

The issue is not merely about street disorder; it is about economic governance. Illicit taxation distorts pricing mechanisms, reduces productivity, discourages the formalisation of businesses, and weakens public trust. If citizens are compelled to pay both official taxes and unofficial levies, compliance morale declines. Why comply with statutory taxation when parallel systems operate unchecked?

Dismantling them is not merely administrative; it is political. Perhaps unbeknownst to the people, the cost of inaction is immense. Lagos aspires to be a 21st-century smart megacity under such an atmosphere. But investors notice informal roadblocks. Businesses factor in unpredictability. Commuters absorb unofficial taxes daily. Across Lagos roads, the script repeats “òwò mi dà,” meaning, give me my money.

Passengers plead with collectors to reduce levies so they can proceed. Conductors argue over dues before departure. Citizens feel hostage to a system they neither elected nor authorised.

Taxation, constitutionally, belongs to the state. It must be legislated, receipted, audited and deployed for the public good.

Agbero taxation is none of these. It is coercive. It is not transparent. It is extractive. Lagos has launched rail lines and BRT corridors. The Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority continues transport reforms. Officials promise that bus reform initiatives will eliminate unregistered operators. But reform cannot be selective. You cannot modernise rail while medieval tolling persists on roads. You cannot preach digital governance while cash collectors flourish at bus stops. You cannot aspire to global city status while informal muscle dictates movement.

The solution is not episodic arrests. It is a structural overhaul: mandatory digital ticketing across all parks; a single harmonised levy payable electronically; an independent audit of union revenue; protection for drivers who resist illegal collections; and political decoupling of unions from patronage networks.

The agbero empire is not merely about bus fares. It is about how patronage systems, once empowered, metastasise into parallel authorities. What may have begun as strategic alliance-building two decades ago has matured into a shadow fiscal regime embedded in daily life.

The challenge is that Lagosians are left with no choice as they now pay twice, once to the government, once to the streets. And unlike official taxes, shadow taxes leave no developmental footprint. No bridge bears their name. No hospital wing testifies to their billions. No classroom is built from their collections. Only inflated fares. Broken windscreens. Frustrated commuters. And drivers who sweat under the sun, calculating how much will remain after everyone has taken their cut.

The agbero question is ultimately a governance question. Is Lagos governed by law, or by tolerated coercion? Is taxation a constitutional function, or a roadside negotiation? Is political convenience worth permanent economic distortion? What is absolutely known is that the structure has a political backing and what politics created, politics can dismantle.

Unless meaningful reform takes place, Lagos will continue to remain a megacity with a shadow treasury, where movement begins not with ignition, but with payment to men who answer to no ledger without any tangible returns. This is to say that every danfo that moves carries not just passengers, but the weight of a system that taxes without law, collects without accountability and punishes the very people who keep the city alive.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn