Feature/OPED

Japa Ideology, Molue, Civilisation and Traveling Abroad for Africans

By Nneka Okumazie

In the history of transportation in Nigeria’s Lagos, there was a Mercedes Benz-911 tractor front converted to a bus used for public transportation called Molue where overloading was common, standing and people clung to the edges, with some of the old buses tilting to the side.

The buses are no longer in use, but in recent videos showing the city, there are red and white buses, separate from the government’s blue-coloured public buses, where there is also often overloading, standings, and some of the buses are tilted sideways.

One era to another, different buses, similar ideology, with nothing done to transform it for years. This means that nothing has changed because what changes is not the object but the thing that runs the object.

A home is to the taste or desire of the occupant, some are painted differently or arranged differently, but it is not often the function of the house, but what runs it. There could be constraints for some choices, but ideology leads whichever way.

There are lots of Africans desirous of leaving the continent, and some of the countries have special names for it. In some situations, it could make sense to leave a bad place for a better place, but to use this as a dominant ideology is erroneous.

Africa may have frustrated some people, but whatever is wrong with Africa is a result of any individual African and the people they like, not the people they know. There is usually this throwaway of responsibility that the continent is bad because of government or foreigners, yes, in some cases, but in general, there is no adult African in Africa who does not have a share of the wrong of the place.

There is responsibility with whatever anyone has or does as an African adult that, if handled better, has a way to prevent deterioration. But people don’t often see what is wrong with what they do or with those they like. It has to be others, so they have to leave the place when they still carry that attitude that does not accept responsibility, and they are guided by the ideology to go somewhere for mostly self-interest, or loyalty for what to gain, or bias for status like others.

Some say their place will never become like other places, but they forget that building is not just the problem; it is maintenance, the character and quality of a people to maintain what they have, correct and build better.

As evil and forceful as slavery was, carried out by foreigners, there were elders and leaders that were excited by things they benefitted for themselves and those they liked, making what could have led to aspects of reforms, technology transfer, or industrial revolution annexation, by collective bargain or negotiations, never fruitful.

There are often situations where many Africans have elevated self-interest over a common interest, subtracting the responsibility of that from the problems their places face. Some African countries are worse, requiring that some leave, but there are people there with responsibilities that could make a difference, but they do nothing.

Some often say they have to travel to possibly have a better future for their children. Most children of recently migrating Africans to new places would do fine, but at an average level, very few would excel at a very high level in the future, but not necessarily for obvious reasons at present. However, a few too would do very badly, doing things their families would never approve of, causing pain and hurt to them and that place.

There are adults too who have left who would get in situations where what they have to do to get themselves out would be things they never believed they could ever do and would not be able to tell anyone, though they would be fine with hypocrisy to judge others, for whatever reasons, continuously.

There are those who think what it means to be better is to have more material things when they have weak values and character. They mend and bend along the self-interest bias of whatever others are doing. They would do whatever it takes to buy things that knowledge built, even as others build new knowledge to build new things they would want to keep buying, remaining in that loop.

In some African countries, people often complain that some tribes have more national political power than others or that they stay in power and are responsible for the decline of the country, maybe or not so. The measure of the excellence of a people is not what they do in other places or positions, it is what they have done for themselves, as a people, at home.

There are tribes where that have power, but their region or home is where they cannot go back to stay. They may exercise power, or what some would call cleverness, elsewhere, but what it means to transform their place is beyond their capability. Those in position also, in their place, have nothing also to offer, so their place is backward and static. They may do well where there seems to be a path, but to create one in their place, they cannot.

This is similar to some foreigners from all over the place in other countries who rise to positions and prominence, the measure of their excellence is not what they do where there is also ready a path, but what they have done for themselves back home, as a people, or how their place is getting transformed, more quickly.

Those back home cannot, those elsewhere cannot, they may seem different, but not that better according to what drives them.

Some people went to other places hundreds of years ago, in expedition and exploration, to find what is elsewhere; they sometimes got into battles, some died, they faced diseases, cold, storms, wrecks, deprivation, etc. Though some of the histories of what they later did were not great, they at least went from their places, say average, better or just ok, to the unknown, which is part of how they dominated and continue to.

There are several Africans who have left for many years, and no one knows them except their family. What it should really mean back home for how they have advanced, to benefit and in responsibility of that edge, is nothing. They may send money to build or do things in the place they left, but for the most part, it makes no difference.

This does not mean there are those who have not excelled because they left or there are those who have not done great, there are many. However, the ideology of leaving as the only possible way to excel is itself a weak value and quality action.

The African who has left and who is leaving should ask, what would this leaving mean to the collective development of the place if people look back in years to come? If the question is too stupid to ask one’s self or to consider, then maybe the same reason some go into government to benefit and loot, for comfort could find a loose parallel with their objective.

[Ezekiel 16:22, And in all thine abominations and thy whoredoms thou hast not remembered the days of thy youth when thou wast naked and bare, and wast polluted in thy blood.]

Feature/OPED

Making Big Shifts: Why Africa’s Boldest Leaders Are Heading to Lagos

History has a way of rewarding leaders who recognise the moment they are in. There are seasons when refinement is enough, and there are moments when only reinvention will do. Africa’s business and leadership landscape is firmly in the latter. Economic pressures are redefining markets, technology is rewriting industries, and organisations are being forced to confront uncomfortable truths about relevance, resilience, and growth. It is within this context that the SHIFT Conference 2026 returns to Lagos, offering not just conversation, but direction.

Built around the theme Making Big Shifts, the conference speaks directly to leaders who understand that incremental progress is no longer sufficient. Across boardrooms and startups alike, leaders are being challenged to rethink how value is created, how people are led, and how institutions remain competitive in an increasingly complex global environment. SHIFT positions itself as a space for honest reflection and bold reimagination.

Curated by The Global Leadership Consultancy and founded by respected leadership thinker, Dr Sam Adeyemi, the SHIFT Conference has evolved into one of Africa’s most influential platforms for leadership and strategic thinking. Its focus is clear: to help leaders move beyond outdated assumptions and equip them with the mindset and tools required to thrive amid constant change. Dr Adeyemi has long maintained that leadership breakdown often begins not with execution, but with thinking. As he has noted, leaders cannot solve today’s problems with yesterday’s mindset, and meaningful transformation only begins when thinking shifts first.

Lagos, as Africa’s commercial heartbeat, provides a fitting backdrop for this conversation. The city’s pace, energy, and entrepreneurial drive reflect the realities leaders face daily. Following a landmark 2025 edition that attracted thousands and sparked wide-ranging conversations, the 2026 conference is expected to draw more than 4,000 participants from across Africa and the diaspora, spanning business, government, technology, finance, and the creative economy.

The speaker lineup underscores the depth of the gathering. The Chief Executive Officer, Global Leadership Consultancy, Dr Sam Adeyemi; Founder and CEO, Axxess, John Olajide and Founder and President of the Women of Destiny, Dr Nike Adeyemi, will anchor discussions that cut across leadership, enterprise, governance, and personal development. Through keynote addresses and interactive conversations, participants will be challenged to confront critical questions around scale, innovation, sustainability, and influence in a fast-evolving world.

Beyond the ideas shared on stage, the SHIFT Conference is intentionally designed as an immersive and practical experience. Attendees will engage in strategy-driven workshops, panel discussions featuring founders and technologists advancing sustainable innovation, and purposeful networking sessions that prioritise meaningful connections. Special experiences tailored for founders, CEOs, and senior executives further reinforce the conference’s focus on high-level decision-making and real-world application.

The credibility and growing influence of the SHIFT Conference are reinforced by the support of leading corporate and media partners, including Alpha Morgan Bank, BusinessDay, Patton Morgan, Jospong, and other institutional sponsors. Their involvement reflects strong confidence in the conference’s vision and its relevance to Africa’s leadership and business ecosystem.

At its core, SHIFT Conference 2026 responds to a defining question facing leaders today: how do you remain relevant in a world that refuses to stand still? The conference’s answer is clear: leaders must be willing to rethink assumptions, make bold strategic choices, and act with clarity and conviction.

For entrepreneurs seeking scale, executives reimagining strategy, public-sector leaders navigating reform, and professionals searching for direction, SHIFT offers more than inspiration. It offers perspective, practical insight, and a community of peers confronting similar challenges and choosing to lead differently.

As leadership continues to evolve, the decision facing many leaders is no longer whether change is coming, but how they will respond to it. That choice will take centre stage at the SHIFT Conference 2026 on Saturday, February 21, 2026, at Eko Hotels & Suites, Victoria Island, Lagos, where Africa’s next chapter in leadership thinking will be shaped.

Feature/OPED

PETROAN, ‘Abiku Refineries’ and the Comfort of Collapse

A sector that keeps reviving what has repeatedly failed, while resisting what works, is not trapped by fate but comforted by collapse. PETROAN’s latest outburst exposes just how invested some interests remain in Nigeria’s ritualised dysfunction.

By Abiodun Alade

Nigeria’s oil and gas sector has endured many seasons of noise masquerading as advocacy. From time to time, pressure is applied not in pursuit of reform, but in defence of habits that have outlived their usefulness. The latest episode is revealing not because it is novel, but because it exposes, with unusual clarity, the discomfort of rent-seeking intermediaries when genuine change threatens familiar margins.

That discomfort has recently found expression in the agitation by the Petroleum Products Retail Outlets Owners Association of Nigeria over comments made by Bayo Ojulari, Group Chief Executive Officer of the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited. In demanding his resignation, PETROAN has inadvertently illuminated a deeper problem in Nigeria’s petroleum political economy: the resistance of entrenched intermediaries to reform that narrows the space for easy rent.

Ojulari’s offence was not misconduct. It was candour. He observed, correctly, that the Dangote Petroleum Refinery has provided breathing space at a time when government-owned refineries are shut, and that the NNPC should not rush back into the familiar ritual of pouring millions of dollars into turnaround maintenance for facilities that have become monuments to waste. This is not heresy; it is prudence.

For a quarter of a century, Nigeria has chased the mirage of refinery rehabilitation. Public records suggest that between $18 billion and $25 billion has been spent on turnaround maintenance and rehabilitation of the four state-owned refineries, with little to show for it. Like the abiku of Yoruba lore, these refineries are revived with ceremony, only to relapse almost immediately. Working today, dying tomorrow. To insist that this cycle must continue, regardless of evidence, is not patriotism. It is sabotage dressed as concern.

PETROAN’s reaction is therefore instructive. In a recent statement, its spokesman, Joseph Obele, described it as “most worrisome” that there was no urgency to restart the Port Harcourt Refinery because Dangote is meeting current fuel needs. The association went further, threatening to lobby civil society groups and pursue legal options to force the removal of the NNPC GCEO should the refinery not resume operations by March 1. This is not policy engagement. It is pressure politics.

Why would a body of retailers, whose business model depends largely on buying and reselling products refined elsewhere, be so hostile to domestic refining capacity? The answer lies in incentives. Domestic refineries compress margins. They reduce arbitrage. They expose inefficiencies that thrive in scarcity. For decades, fuel importation and the dysfunction it encouraged created space for unearned profits across the value chain. Local refining threatens that arrangement.

History offers a useful parallel. In Mancur Olson’s classic work The Logic of Collective Action, he explains how small, organised interest groups often prevail over the broader public interest because they are better motivated to defend narrow gains. PETROAN’s conduct fits this pattern. It speaks loudly, often, and with confidence, but for whom does it really speak?

It is also worth recalling PETROAN’s posture during earlier periods of distress in the sector. At moments when the national oil company was accumulating unsustainable obligations, remitting little or nothing to the Federation Account and absorbing enormous costs, commendations flowed freely. Laurels were dished out even as the system bled. That era ended with the Federal Government writing off substantial debts, including about $1.42 billion and N5.57 trillion after reconciliation. Nigerians paid the price for that indulgence.

During the years when Nigeria’s petroleum sector was driven to the brink, PETROAN looked the other way. The record is clear. The national oil company captured the entire value chain, seizing crude exports, monopolising refined product imports, and then forcing the Federal Government to borrow an estimated N500 billion monthly to sustain opaque subsidy claims. By controlling nearly 90 per cent of the roughly $3 billion in monthly crude proceeds routed through the Central Bank, and combining this with subsidy payments and other shocks, fiscal space collapsed, driving the government into massive Ways and Means financing.

At the same time, refinery rehabilitation became an industry without output. About $10 billion was spent over a decade on maintenance with nothing to show for it, not even a litre of petrol. A further $3 billion was later securitised against future crude sales for yet another failed repair cycle, a sum that could have delivered dozens of modular refineries. Even after the Petroleum Industry Act prioritised Domestic Crude Obligation, compliance remained elusive, while Nigeria continued to burn scarce foreign exchange importing substandard fuel into a system with no functional midstream. These were not marginal errors but a business model that plunged the country into crisis. Throughout it all, PETROAN’s voice was conspicuously muted, generous with praise where scrutiny was required.

This is why the current agitation rings hollow. Reform always unsettles those who prospered under disorder. President Bola Tinubu’s administration has signalled, through words and decisions, that it intends to break with the old script. Ojulari’s mandate at NNPC is clear: commercial discipline, efficiency and profitability. That mandate cannot be reconciled with endless rehabilitation theatre.

There is another uncomfortable question PETROAN has not answered. What value does its leadership bring to the petroleum sector beyond television appearances and press statements? Serious business leadership is measured in assets built, jobs created and value added. Publicly available information suggests that some of the companies associated with PETROAN’s leadership are modest in scale, with limited project footprints. Allegations and controversies reported in the public domain around some of these entities, whether in the power metering space or elsewhere, only reinforce the need for caution in elevating moral authority. Perhaps PETROAN’s members would do well to examine the records of those who speak in their name before an association meant to represent many is reduced to the private estate of a few and recast as an adversary of the public interest.

This is not to say that retailers have no role in policy debate. They do. But influence must be earned through insight, integrity and alignment with the national interest. Threats and ultimatums betray a lack of confidence in argument.

Nigeria stands at a fork in the road. One path leads back to ritualised waste, institutional failure and the comfort of familiar inefficiencies. The other leads to local capacity, competition and a petroleum industry that finally works for Nigerians. The Dangote Refinery is not a silver bullet, but it is a signal that the old excuses are losing credibility.

PETROAN’s nuisance value thrives only when reformers flinch. President Tinubu has shown little appetite for cheap blackmail. Ojulari enjoys his confidence for a reason. The task before NNPC is too important to be derailed by those nostalgic for a broken system. If PETROAN wishes to be relevant in this new era, it must evolve from noise to nuance. Otherwise, history will remember it not as a defender of consumers, but as a footnote in Nigeria’s long struggle to escape the tyranny of waste.

Abiodun, a communications specialist, writes from Lagos

Feature/OPED

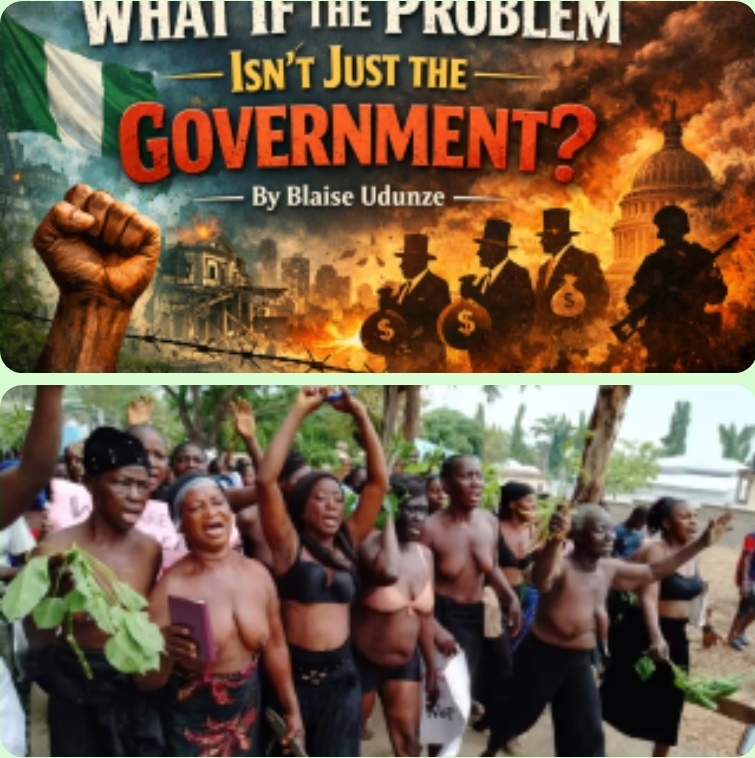

What If the Problem Isn’t Just the Government?

By Blaise Udunze

Recent reports in the media space highlighting threats of “naked protests” by market women across several states if the federal government fails to address the issue of hardship underscore the depth of hunger and poverty gripping the nation. No doubt, there is hardship in the country, of which Nigeria’s poverty crisis is often framed as the government’s failure, poor policies, weak institutions, corruption, and economic mismanagement.

From a balanced viewpoint, while these factors are undeniable, they do not tell the full story in its totality. The reality is that the majority of Nigerians, being the larger populace experiencing this challenge, will definitely oppose the ideology that poverty in Nigeria is not merely a policy problem; it is also a societal one. The underlying truth is that this is shaped by citizens’ behaviours, choices, cultural norms, and civic attitudes. This will remain a lived experience of the people until this dimension is confronted honestly; reforms will continue to yield limited results.

Nigeria’s economy has witnessed growth as inflation has decelerated, with headline inflation easing to 15.15percent and food inflation retreating to 10.84 per cent. The exchange rate was stabilising, and foreign reserves ($46.7 billion) had climbed to a seven-year peak. Despite the growth figures and ambitious government targets, millions of Nigerians remain trapped in poverty. More alarming is the recent estimates suggesting that an additional two million people could fall below the poverty line this year alone.

The intrigue is that the geographic distribution of these figures tells a deeper story, and this is more revealing than the numbers; however, there is an uneven geographical spread. Of concern here, which is troubling, is why states such as Yobe, Jigawa, Katsina, Kano, and Zamfara tend to experience or be deep in poverty when compared to other states like Lagos, Port Harcourt, Aba, Enugu, and Onitsha, which are projected to experience less poverty. This disparity raises a critical question, which calls for an urgent answer to why poverty outcomes differ so starkly within the same country, because no doubt, much of the explanation lies beyond government failures.

While governance challenges exist nationwide, the explanation extends beyond Abuja. Perhaps this is from deliberate ignorance of the people; the reality is that it lies in education, cultural practices, social norms, and individual responsibility play decisive roles in shaping economic outcomes.

One key alarming fact that has deeply entrenched poverty in many northern states, unlike other regions, is limited access to education, especially for girls, early marriage, polygamy, and large family sizes. There have been several factors that reinforce cycles of poverty by stretching limited household resources, reducing educational attainment, and limiting economic mobility, and this will continue to be a long-standing challenge or lived experience for the people if not addressed.

It is clearer that practical comparison illustrates this reality. Taking into consideration that a low-income worker in Yobe who marries four wives and raises over twenty children will inevitably struggle to provide adequate education, healthcare, and opportunities for his family, while in contrast, a similar worker in Aba is more likely to marry later, have fewer children, and invest in their education. Without much ado, over time, the children in the latter household acquire skills, productivity, and economic relevance because their parents chose to prioritise education for them, while the former remain trapped in subsistence and dependency. These differences are not subjective; they are structural and measurable.

Religion and culture further complicate the picture as record has it that Nigeria is one of the most religious countries in the world, yet religiosity often serves personal aspirations, prosperity, miracles, or divine favour rather than reinforcing civic responsibility and social ethics. Today in Nigeria, political leaders frequently reinforce this distortion and moral narrative. Only recently, it was announced that public officials in Abuja celebrate marrying off multiple children at once, some governors borrow billions to spend public funds on religious pilgrimages, while underfunding education, healthcare, and infrastructure, they send a clear message about priorities. In contrast, states that invest deliberately in education, such as Enugu with its smart school initiatives, demonstrate how leadership choices influence societal outcomes.

Still, the crisis of responsibility is not confined to any region. It is national, as proved during the discussions at Lagos State’s 12th Summit of the Association of Retired Heads of Service and Permanent Secretaries (ALARHOSPS), it was emphasised that societal progress depends not only on leadership but on citizenship behaviour. According to Professor Wusu Onipede, citizenship is defined by commitment to collective welfare, not mere residence.

The truth is not far-fetched, going by the saying that actions, positive or negative, directly impact society. What would have informed the common actions, such as stealing public assets, vandalising infrastructure, ignoring traffic laws, or tolerating corruption, all accumulate into widespread societal harm as seen in our everyday lives. Conversely, volunteering, mentorship, and community engagement generate resilience, opportunity, and shared prosperity. With close reading, one will notice that this dynamic was captured succinctly in Professor Oluwatomi Alade’s “Triangle for Change,” which pointed to the home, the school, and the community. Parents must brace up to understand that the primary responsibility is upon them to start prioritising education, teachers who impart both knowledge and character, and communities that uphold civic values create the foundation for sustainable development because the truth is that the change does not only rest on the government. In the same manner, it will be said that neglect in any of these spheres, whether through early marriage, disregard for schooling, or normalisation of polygamy, undermines national progress.

Religious institutions, as Professor Oguntola-Laguda argues, must also evolve, which means that beyond spiritual teachings, they should emphasise practical social ethics in the areas of responsibility, productivity, gender inclusion, and civic duty. In regions where harmful norms persist, faith leaders, traditional authorities, and elders possess the influence necessary to drive change, if they choose not to use it, otherwise the society will remain impoverished.

Globally, the link between social norms and poverty is well established, and norms that condone child marriage, gender exclusion, or unchecked family sizes perpetuate intergenerational deprivation. Over the period, in other countries, it is clear that economic interventions alone cannot dismantle these patterns because countries like India show that combining education incentives, political inclusion, and social protection can reduce poverty among marginalised groups. Initiatives such as Uganda’s SASA, which is a program that demonstrates that shifting attitudes toward gender and empowerment lead to improved economic outcomes. Nigeria’s poverty strategy must similarly integrate social transformation with economic reform.

None of this absolves government responsibility. Poorly sequenced reforms, rising taxes, insecurity, weak infrastructure, and inadequate social protection continue to deepen hardship. Senator David Mark of the African Democratic Congress has criticised what he terms “vicious policies” that worsen citizens’ vulnerability. Nigerians are acutely aware of these failures. What they demand is not statistics or political rhetoric, but practical policies that reduce hardship, enable productivity, and promote inclusion.

Even at this, Nigerians must take into cognisance that government action alone is insufficient. Poverty cannot be eradicated where large families are unsustainable, education is undervalued, and corruption is tolerated at the household and community levels. Individual responsibility remains the missing link. Citizens must be discreet in their timing for marriage until they can provide adequately, manage family sizes responsibly, educate all children, especially girls and reject the glorification of excess and impunity.

Insecurity further illustrates this shared responsibility. Though one will argue that the state bears the constitutional duty to protect lives and property, law and order, what about the dwellers? Communities must actively support security efforts through vigilance, information sharing, and conflict resolution. Silence in the face of crime and corruption enables disorder because independence loses meaning when citizens disengage from safeguarding their own communities.

Another critical aspect that is akin to insecurity is that economic development also falters when citizens undermine progress through dishonesty, rent-seeking, and apathy. What people fail to understand is that entrepreneurship, accountability, and cooperation are as vital as government-led job creation. The same thing can be said of cooperatives, vocational training, and local enterprise, which can deliver immediate relief and long-term sustainability. Wealthier Nigerians must focus on genuine social investment, creating opportunities, supporting education, and building institutions that outlast personal interest or individual generosity, rather than charity or wasteful spending or fueling crimes. Social responsibility must become a social norm.

One laughable misconception people harbour about independence, which must be clarified, is that it is not simply freedom from colonial rule; it is the presence of civic responsibility. It must be understood that poverty persists not only because of policy gaps but because of harmful norms, cultural practices, and neglected duties. Anyone can argue this, but the truth is that there will always be a replay of this menace kicked against because every child denied education, every early marriage, every act of corruption, reinforces the cycle.

Breaking this repeating problem, known as poverty, takes several coordinated strategies working together, not just one solution. There must be an understanding that the issues are complex and interconnected; they must be addressed from different angles at the same time. For these reasons, the government must provide stable policies, infrastructure, and social protection and the citizens, in like manner, must reform behaviours that perpetuate poverty. The same must be said of the families that must prioritise education, and also, the communities must reward civic engagement and innovation. Religious and cultural leaders must promote responsibility alongside faith because these are critical platforms that have the attention of the greater number of people. The policymakers at this juncture must ensure that policies not only deliver relief but also incentivise behaviours that support sustainable development.

Without too much argument, it is glaring that Nigeria’s potential is evident in states and communities that have embraced education, civic virtue, and social reform. Judging by the developments in different states, one will conclude that Lagos demonstrates how engagement and accountability improve outcomes, while Enugu shows that investing in children yields long-term dividends. Conversely, regions where harmful norms persist remain trapped, regardless of federal spending.

Without much ado, all Nigerian stakeholders must come to the terms that Nigeria’s poverty challenge cannot be reduced to government failure alone. It is a collective problem rooted in culture, norms, and personal choices because sustainable development demands both accountable leadership and responsible citizenship. The fact remains that poverty will remain an enduring shadow, irrespective of the repeated threats of “naked protests,” but until Nigerians fully embrace their role as architects, not just beneficiaries of national progress. True independence begins when citizens accept that the future of the nation rests as much in their daily choices as in public policy.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: [email protected]

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism9 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn