Feature/OPED

May 29 and Quest for A New Nigeria

By Jerome-Mario Chijioke Utomi

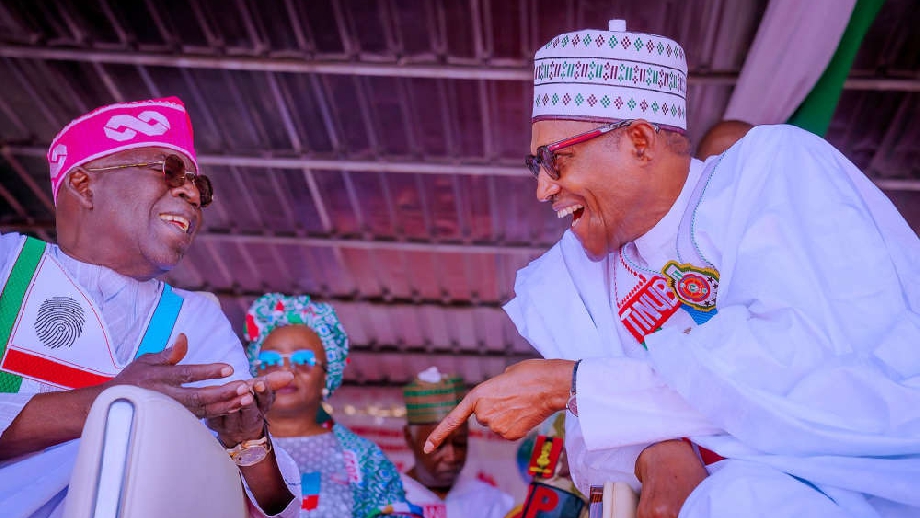

As the nation Nigeria stands at the exit door of President Muhammadu Buhari-led federal government and gazes at the May 29 inauguration date of incoming administrations at both state and federal government levels, it is important to underline that the protracted leadership crisis witnessed at both state and federal levels occurred not because the democracy and federal systems we practice are on their own bad or unable to provide the needed solution to the nation’s array of political and economic needs, but because too many politicians and public office holders exercised power and responsibility not as a trust for the public good, rather, but as an opportunity for private gain.

This glaringly deformed leadership style has left the nation with three separate but similar harsh effects; first, it destroyed the social infrastructures relevant for a meaningful and acceptable level of the social existence of the people.

Secondly, making the nation’s economy go against the provisions of the constitutions as an attempt to disengage governance from public sector control of the economy has only played into waiting for the hands of the profiteers of goods and services to the detriment of the Nigerian people.

Thirdly and very key, conspired and visited the nation with myriads of sociopolitical contradictions stripped of social harmony, justice, equity and equality.

Adding context to the discourse, this is a kind of leadership crisis that happens when ‘lust for power prevails over granting people the love and care they deserve, when the interest and destiny of one individual become more important than those of the whole nation when the interests of some groups and cliques are served instead of those of all the people. In other words, this state of affairs happens when you put the people at the service of the government, in sharp contrast with the norm.

Aside from non-adherence to public opinion, which has no doubt thrown the economy into reserve and passed the burden onto the backs of Nigerians, this piece believes that the most ‘profound’ failure of the present administration (state and Federal) which the incoming administration must avoid if they are desirous of success, is their persistent inabilities to promptly respond to the socioeconomic need of Nigerians.

For example, the government’s shift of attention from job creation has undermined the feelings of Nigerians and shifted the distribution of income strongly in favour of those in government.

At the very moment, information released on April 11, 2023, by KPMG, a multidimensional consulting firm, disclosed that Nigeria’s unemployment rate would increase to 40.6 per cent in 2023 from 37.7 per cent in 2022. According to economic analysts, this was due to weak performance in the job-elastic sectors and low labour absorption of sectors that will drive growth.

In my view, the average Nigerian is worse off now, economically and materially, than he/she was in 2015. The people are living through the worst social and economic crisis since independence; poor leadership; poor strategy for development; lack of capable and effective state and bureaucracy; lack of focus on sectors that will improve the condition of living of citizens, such as education, health, agriculture and the building of infrastructure; corruption; undeveloped, irresponsible and parasitic private sector; weak civil society; emasculated labour and student movement and poor execution of policies and programmes’.

In the past 8years, the Nigerian workforce grew, but the number of manufacturing jobs has actually declined as a result of the relocation of these industries to neighbouring African countries. A development occasioned by the inability of the FG to guarantee security and electricity.

Jobs created by the federal government under the N-Power programme were part-time and not secured. Two third of those doing part-time jobs want full-time jobs and cannot find them. Unemployment is far and away from the top concern of Nigerians. Millions of workers have given up hope of finding employment.

This author is not alone in this line of belief.

At a recent lecture in Lagos delivered by the President of the African Development Bank (AfDB), Dr Akinwumi Adesina, titled: Nigeria – A Country of Many Nations: A Quest for National Integration, Dr Adesina lamented the high rate of joblessness among Nigerians, saying about 40 per cent of youths were unemployed. While noting that the youths were discouraged, angry and restless as they looked at a future that did not give them hope, he said all hope was not lost as youths have a vital role to play if the country should arrive at its destined destination.

Adesina spoke the mind of Nigerians. His words and argument were admirable, and most importantly, it remains the most dynamic and cohesive action expected of a leader of his class to earn a higher height of respect. The truth is that Nigerians have gotten used to such statistics while unemployment commentaries in the country have become a regular music hall act.

Take as an illustration, in the first quarter of 2021, a report published by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) on its website noted that Nigeria’s Unemployment Rate has risen from 27.1 per cent in the second quarter of 2020 to 33 per cent. Aside from making it the second highest on Global List, the NBS report, going by analysis, shows that ‘more than 60 per cent of Nigeria’s working-age population is younger than 34.

Unemployment for people aged 15 to 24 stood at 53.4 per cent in the fourth quarter and at 37.2 per cent for people aged 25 to 34. The jobless rate for women was 35.2 per cent compared with 31.8 per cent for men.

The recovery of the economy with 200 million people will be slow, with growth seen at 1.5 per cent this year, after last year’s 1.9 per cent contraction, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The output will only recover to pre-pandemic levels in 2022, the lender said. The number of people looking for jobs will keep rising as population growth continues to outpace output expansion.

Nigeria is expected to be the world’s third-most-populous country by 2050, with over 300 million people, according to the United Nations. Unquestionably, while this quadrupling over the last five years, which has attracted varying reactions from well-meaning Nigerians, remains a sad commentary by all ramifications as it is both worrying and scary, the present development demands two separate but similar actions. First is the urgent shift from lamentation and rhetoric to finding solutions by asking solution-oriented questions. The second has to do with the implementation of experts’ advice/solutions to unemployment in Nigeria. This is indeed time to commit to mind the words of Franklin D. Roosevelt, former President of the United States of America, that “extraordinary conditions call for extraordinary remedies.”

Beginning with questions, it has become important for the incoming administration to ask what could be responsible for the ever-increasing unemployment rate in Nigeria. Is it leadership or the nation’s educational system? If it is faulty education sector-driven, what is the government (both state and federal) going to do to rework the policies since education is in the concurrent list of the nation’s 1999 constitution (as amended)? Are the leaders embodied with leadership virtues that the global community can respect? Or moral and ethical principles the people can applaud with enthusiasm?

Experts have pointed out that to arrest the drifting unemployment situation in the country, four sectors of ‘interest’ to watch are education, science and technology, agriculture and infrastructure.

On the educational system in the country, analysts are of the view that the education policies of the 6-3-3-4 system are excellent in the policy statement, but the inability of the financiers to provide the teaching tools for its success has truncated its intended goal and objectives. However, to arrest the unemployment challenge, they added, entrepreneurial programmes should be integrated into the educational system from primary schools to universities. Creativity, courage and endurance are skills that should be taught by psychologists to students in all classes of our educational system.

Nigeria, they explained, has to increase the number of her current Polytechnics, Colleges of Technology and Technical Colleges drastically in relation to the in-explicable very large number of Universities and related Academies in Nigeria’s economy in order to clearly address the training and development of professional and technical skills for Technologies and Industrial goods production in Nigeria’s Economy.

It is important, in my view, that any country like Nigeria, desirous of achieving sustainable development, must throw its weight behind agriculture by creating an enabling environment that will encourage youths to take to farming. First, separate from the worrying report that by 2050, global consumption of food and energy is expected to double as the world’s population and incomes grow, while climate change is expected to have an adverse effect on both crop yields and the number of arable acres, we are in dire need of solution to this problem because unemployment has diverse implications. Security-wise, a large unemployed youth population is a threat to the security of the few that are employed. Any transformation that does not have job creation as its main objective will not take us anywhere, and the agricultural sector has the capacity to absorb the teeming unemployed youths in the country.

The second reason is that globally, there are dramatic shifts from agriculture in preference for the white-collar jobs-a trend that urgently needs to be reversed. In the United States of America, there exists a shift in the locations and occupations of urban consumers. In 1900, about 40 per cent of the total population was employed on the farm, and 60 per cent lived in rural areas. Today, the respective figures are only about one per cent and 20 per cent.

Over the past half-century, the number of farms has fallen by a factor of three. As a result, the ratio of urban eaters to rural farmers has markedly risen, giving the food consumer a more prominent role in shaping the food and farming system. The changing dynamic has also played a role in public calls to reform federal policy to focus more on the consumer implications of the food supply chain.

Separate from job creation, averting malnutrition which constitutes a serious setback to the socio-economic development of any nation, is another reason why Nigeria must embrace agriculture – a vehicle for food security and a sustainable socio-economic sector. Agriculture production should receive heightened attention. In Nigeria, an estimated 2.5 million children under five suffer from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) annually, exposing nearly 420,000 children within that age bracket to early death from common childhood illnesses such as diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria. Government must provide the needed support through funding, providing technical know-how and other specialised training.

For Nigeria to be all that it can be, the youth of Nigeria must be all they can be.” The future of Nigeria depends on what it does today with its dynamic youth population. This demographic advantage must be turned into a first-rate and well-trained workforce, for Nigeria, for the region, and for the world. The incoming administration must prioritise investments in the youth: in upskilling them for the jobs of the future, not the jobs of the past; by moving away from so-called youth empowerment to youth investment; to opening up the social and political space to the youth to air their views and become a positive force for national development; and for ensuring that we create youth-based wealth.”

On the imperatives of Infrastructural development such as roads, rail and electricity, the incoming government must recognize the fact that infrastructure enables development and provides the services that underpin the ability of people to be economically productive, for example, via transport. “The transport sector has a huge role in connecting populations to where the work is,” says Ms Marchal. Infrastructural investments help stem economic losses arising from problems such as power outages or traffic congestion. The World Bank estimates that in Sub-Saharan Africa, closing the infrastructure quantity and quality gap relative to the world’s best performers could raise GDP growth per head by 2.6 per cent annually.

For us to achieve the target objective in the rail sector, the incoming government must start thinking of a rail system that will have a connection of major economic towns/cities as the focus.

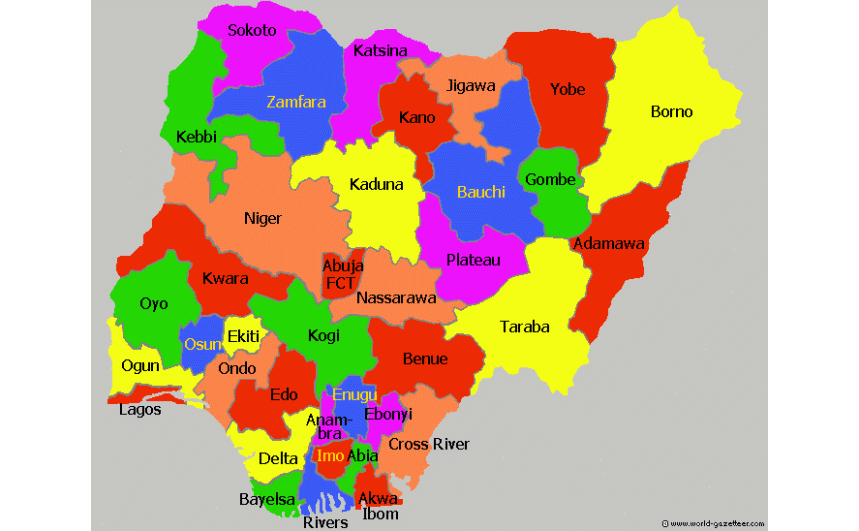

Achieving this objective will help the poor village farmers in Benue/Kano and other remote areas earn more money, contributes to lower food prices in Lagos and other cities through the impact on the operation of the market, increase the welfare of household both in Kano, Benue, Lagos and others while it improves food security in the country, reduce stress/pressure daily mounted on Nigerian roads by articulated/haulage vehicles and drastically reduce road accidents on our major highways.

In the area of electricity/power generation and distribution, there is an urgent imperative for the incoming government to openly admit and adopt both structural and managerial changes that impose more leadership discipline than conventional and create government institutions that are capable of making successful decisions built on a higher quality of information which needs to be granted.

To give an example, in 2005 and 2010, Chief Olusegun Obasanjo and Dr Goodluck Ebele Jonathan-led the federal government, respectively, came up with the electric power sector reform, EPSR, ACT 2005 and the roadmap for power sector reform of 2010, which was targeted at sanitizing the power sector, ensure efficient and adequate power supply to the country. The project ended in the frames – reportedly gulping billions of dollars without contributing the targeted megawatt to the nation’s power needs.

The Buhari-led administration is presently in a similar partnership with the German government and Siemens. But in my observation, the only change that has taken place since this new development is thoughtless increments of bills/tariffs paid by Nigerians.

No nation can survive under this form of arrangement.

Finally, while this piece calls on the incoming government to provide Nigerians with a standard of living adequate for their health and well-being, Nigerians, on their part, must look up to God, their maker and talk to him through positive actions. They must join their faith with that of James Weldon Johnson to pray; ‘Oh God of our weary years, God of our silent tears, Thou hast us far on the way; Thou who by the might lead us into the light. Keep us forever in part we pray lest our feet stray away from places, our God where we meet thee. Lest our heart is drunk with the wine of the world, and we forget thee; Shadowed beneath thy hand, may we forever stand true to our God, true to our native land’. To this, I say a very big amen.

Jerome-Mario is the programme coordinator (Media and Public Policy) for Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA). He can be reached via Je*********@***oo.com/08032725374

Feature/OPED

How Christians Can Stay Connected to Their Faith During This Lenten Period

It’s that time of year again, when Christians come together in fasting and prayer. Whether observing the traditional Lent or entering a focused period of reflection, it’s a chance to connect more deeply with God, and for many, this season even sets the tone for the year ahead.

Of course, staying focused isn’t always easy. Life has a way of throwing distractions your way, a nosy neighbour, a bus driver who refuses to give you your change, or that colleague testing your patience. Keeping your peace takes intention, and turning off the noise and staying on course requires an act of devotion.

Fasting is meant to create a quiet space in your life, but if that space isn’t filled with something meaningful, old habits can creep back in. Sustaining that focus requires reinforcement beyond physical gatherings, and one way to do so is to tune in to faith-based programming to remain spiritually aligned throughout the period and beyond.

On GOtv, Christian channels such as Dove TV channel 113, Faith TV and Trace Gospel provide sermons, worship experiences and teachings that echo what is being practised in churches across the country.

From intentional conversations on Faith TV on GOtv channel 110 to true worship on Trace Gospel on channel 47, these channels provide nurturing content rooted in biblical teaching, worship, and life application. Viewers are met with inspiring sermons, reflections on scripture, and worship sessions that help form a rhythm of devotion. During fasting periods, this kind of consistent spiritual input becomes a source of encouragement, helping believers stay anchored in prayer and mindful of God’s presence throughout their daily routines.

To catch all these channels and more, simply subscribe, upgrade, or reconnect by downloading the MyGOtv App or dialling *288#. You can also stream anytime with the GOtv Stream App.

Plus, with the We Got You offer, available until 28th February 2026, subscribers automatically upgrade to the next package at no extra cost, giving you access to more channels this season.

Feature/OPED

Turning Stolen Hardware into a Data Dead-End

By Apu Pavithran

In Johannesburg, the “city of gold,” the most valuable resource being mined isn’t underground; it’s in the pockets of your employees.

With an average of 189 cellphones reported stolen daily in South Africa, Gauteng province has become the hub of a growing enterprise risk landscape.

For IT leaders across the continent, a “lost phone” is rarely a matter of a misplaced device. It is frequently the result of a coordinated “snatch and grab,” where the hardware is incidental, and corporate data is the true objective.

Industry reports show that 68% of company-owned device breaches stem from lost or stolen hardware. In this context, treating mobile security as a “nice-to-have” insurance policy is no longer an option. It must function as an operational control designed for inevitability.

In the City of Gold, Data Is the Real Prize

When a fintech agent’s device vanishes, the $300 handset cost is a rounding error. The real exposure lies in what that device represents: authorised access to enterprise systems, financial tools, customer data, and internal networks.

Attackers typically pursue one of two outcomes: a quick wipe for resale on the secondary market or, far more dangerously, a deep dive into corporate apps to extract liquid assets or sellable data.

Clearly, many organisations operate under the dangerous assumption that default manufacturer security is sufficient. In reality, a PIN or fingerprint is a flimsy barrier if a device is misconfigured or snatched while unlocked. Once an attacker gets in, they aren’t just holding a phone; they are holding the keys to copy data, reset passwords, or even access admin tools.

The risk intensifies when identity-verification systems are tied directly to the compromised device. Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), widely regarded as a gold standard, can become a vulnerability if the authentication factor and the primary access point reside on the same compromised device. In such cases, the attacker may not just have a phone; they now have a valid digital identity.

The exposure does not end at authentication. It expands with the structure of the modern workforce.

65% of African SMEs and startups now operate distributed teams. The Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) culture has left many IT departments blind to the health of their fleet, as personal devices may be outdated or jailbroken without any easy way to know.

Device theft is not new in Africa. High-profile incidents, including stolen government hardware, reinforce a simple truth: physical loss is inevitable. The real measure of resilience is whether that loss has any residual value. You may not stop the theft. But you can eliminate the reward.

Theft Is Inevitable, Exposure is Not

If theft cannot always be prevented, systems must be designed so that stolen devices yield nothing of consequence. This shift requires structured, automated controls designed to contain risk the moment loss occurs.

Develop an Incident Response Plan (IRP)

The moment a device is reported missing, predefined actions should trigger automatically: access revocation, session termination, credential reset and remote lock or wipe.

However, such technical playbooks are only as fast as the people who trigger them. Employees must be trained as the first line of defence —not just in the use of strong PINs and biometrics, but in the critical culture of immediate reporting. In high-risk environments, containment windows are measured in minutes, not hours.

Audit and Monitor the Fleet Regularly

Control begins with visibility. Without a continuous, comprehensive audit, IT teams are left responding to incidents after damage has occurred.

Opting for tools like Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) allows IT teams to spot subtle, suspicious activities or unusual access attempts that signal a compromised device.

Review Device Security Policies

Security controls must be enforced at the management layer, not left to user discretion. Encryption, patch updates and screen-lock policies should be mandatory across corporate devices.

In BYOD environments, ownership-aware policies are essential. Corporate data must remain governed by enterprise controls regardless of device ownership.

Decouple Identity from the Device

Legacy SMS-based authentication models introduce avoidable risk when the authentication channel resides on the compromised handset. Stronger identity models, including hardware tokens, reduce this dependency.

At the same time, native anti-theft features introduced by Apple and Google, such as behavioural theft detection and enforced security delays, add valuable defensive layers. These controls should be embedded into enterprise baselines rather than treated as optional enhancements.

When Stolen Hardware Becomes Worthless

With POPIA penalties now reaching up to R10 million or a decade of imprisonment for serious data loss offences, the Information Regulator has made one thing clear: liability is strict, and the financial fallout is absolute. Yet, a PwC survey reveals a staggering gap: only 28% of South African organisations are prioritising proactive security over reactive firefighting.

At the same time, the continent is battling a massive cybersecurity skills shortage. Enterprises simply do not have the boots on the ground to manually patch every vulnerability or chase every “lost” terminal. In this climate, the only viable path is to automate the defence of your data.

Modern mobile device management (MDM) platforms provide this automation layer.

In field operations, “where” is the first indicator of “what.” If a tablet assigned to a Cape Town district suddenly pings on a highway heading out of the city, you don’t need a notification an hour later—you need an immediate response. An effective MDM system offers geofencing capabilities, automatically triggering a remote lock when devices breach predefined zones.

On Supervised iOS and Android Enterprise devices, enforced Factory Reset Protection (FRP) ensures that even after a forced wipe, the device cannot be reactivated without organisational credentials, eliminating resale value.

For BYOD environments, we cannot ignore the fear that corporate oversight equates to a digital invasion of personal lives. However, containerization through managed Work Profiles creates a secure boundary between corporate and personal data. This enables selective wipe capabilities, removing enterprise assets without intruding on personal privacy.

When integrated with identity providers, device posture and user identity can be evaluated together through multi-condition compliance rules. Access can then be granted, restricted, or revoked based on real-time risk signals.

Platforms built around unified endpoint management and identity integration enable this model of control. At Hexnode, this convergence of device governance and identity enforcement forms the foundation of a proactive security mandate. It transforms mobile fleets from distributed risk points into centrally controlled assets.

In high-risk environments, security cannot be passive. The goal is not recovery. It is irrelevant, ensuring that once a device leaves authorised hands, it holds no data, no identity leverage, and no operational value.

Apu Pavithran is the CEO and founder of Hexnode

Feature/OPED

Daniel Koussou Highlights Self-Awareness as Key to Business Success

By Adedapo Adesanya

At a time when young entrepreneurs are reshaping global industries—including the traditionally capital-intensive oil and gas sector—Ambassador Daniel Koussou has emerged as a compelling example of how resilience, strategic foresight, and disciplined execution can transform modest beginnings into a thriving business conglomerate.

Koussou, who is the chairman of the Nigeria Chapter of the International Human Rights Observatory-Africa (IHRO-Africa), currently heads the Committee on Economic Diplomacy, Trade and Investment for the forum’s Nigeria chapter. He is one of the young entrepreneurs instilling a culture of nation-building and leadership dynamics that are key to the nation’s transformation in the new millennium.

The entrepreneurial landscape in Nigeria is rapidly evolving, with leaders like Koussou paving the way for innovation and growth, and changing the face of the global business climate. Being enthusiastic about entrepreneurship, Koussou notes that “the best thing that can happen to any entrepreneur is to start chasing their dreams as early as possible. One of the first things I realised in life is self-awareness. If you want to connect the dots, you must start early and know your purpose.”

Successful business people are passionate about their business and stubbornly driven to succeed. Koussou stresses the importance of persistence and resilience. He says he realised early that he had a ‘calling’ and pursued it with all his strength, “working long weekends and into the night, giving up all but necessary expenditures, and pressing on through severe setbacks.”

However, he clarifies that what accounted for an early success is not just tenacity but also the ability to adapt, to recognise and respond to rapidly changing markets and unexpected events.

Ambassador Koussou is the CEO of Dau-O GIK Oil and Gas Limited, an indigenous oil and natural gas company with a global outlook, delivering solutions that power industries, strengthen communities, and fuel progress. The firm’s operations span exploration, production, refining, and distribution.

Recognising the value of strategic alliances, Koussou partners with business like-minds, a move that significantly bolsters Dau-O GIK’s credibility and capacity in the oil industry. This partnership exemplifies the importance of building strong networks and collaborations.

The astute businessman, who was recently nominated by the African Union’s Agenda 2063 as AU Special Envoy on Oil and Gas (Continental), admonishes young entrepreneurs to be disciplined and firm in their decision-making, a quality he attributed to his success as a player in the oil and gas sector. By embracing opportunities, building strong partnerships, and maintaining a commitment to excellence, Koussou has not only achieved personal success but has also set a benchmark for future generations of African entrepreneurs.

His journey serves as a powerful reminder that with determination and vision, success is within reach.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn