Feature/OPED

Peter Enahoro, Legacies And Lessons

By Jerom-Mario Chijioke Utomi

Though it’s been long known via research that when traumatic events –those involving anxiety and pains occur or are told to those who feel linked by identity to the victims- whether the shared identity is ethnic, religious, historical, cultural, linguistic or nationalistic, it can never produce emotional and physical responses similar to those experienced by the victims.

The above fact notwithstanding, Nigerians a few days ago received with rude shock, disbelief and excruciating pain the news about the demise of Mr Peter Enahoro, eminent satirist, celebrated author, and journalist-extraordinaire. To many, the pains that emanated from that news were, to an appreciable extent, similar to that of the victim.

Adding context to the piece, Peter Enahoro, who passed on at the ripe age of 88, was ‘raw talent’ when he joined the Daily Times in 1955 and became editor of the Sunday Times in 1958 at the tender age of 23. He became the editor of the group, the Daily Times in 1962 at 27. In 1965, he was made the Editor-in-Chief of the Daily Times conglomerate. He was just 30. He was young, restless, cerebral, eager and courageous.

Peter, going by records, was blessed with mastery of the English Language and a deep understanding of our society. He was an incurable wit who soon got a large following. He wrote his Peter Pan column twice weekly.

Aside from practising journalism that qualifies as pro-people, and in sharp contrast with present-day journalism, there are, in the opinion of this piece, very sterling legacies he left behind that present-day journalists must draw lessons from.

First and very fundamental, throughout his period of practice, he recognized and demonstrated that as a journalist, he should watch the society and not be watched over; that he should watch over crimes, injustices, malpractices, and every other act deemed unfair and unlawful. He was not the kind of ‘watchdog’ with ropes tied around his neck and so had no freedom of speech and expression.

He knew what to do, where to go, and how to discharge his duties when due and should not be dictated by any force or power whatsoever. Professionally, he was capped with competence to carry out the duties as a vibrant member of the fourth estate of the realm.

To ensure that this standard was upheld, the Uromi, Edo state-born Enahoro went into a self-imposed exile that lasted for 13 years. That was in the 1960s. While abroad, he functioned as the Contributing Editor of Radio Deutsche Welle in Cologne, Germany, from 1966 to 1976, and was the Africa Editor of National Zeitung in Basel, Switzerland, becoming Editorial Director of New African magazine in London in 1978.

Secondly, he supported the positive purpose of the elected government that did not in any way dent/obstruct the media’s primary responsibility to the masses in a democratic society. He used his writing to inculcate and reinforce positive political, cultural, and social attitudes among the citizens. He created a mood in which Nigerians became keen to acquire skills and disciplines of developed nations.

But he stood stoutly against military rule in Nigeria even at a time when it was considered fashionable to support military rule.

His attributes as a journalist say something more worthy of emulation.

Take, as an illustration, Peter going by his actions and inactions as a journalist, was among the very few who believed that ‘a free press is not a privilege but an organic necessity in a great society. For without criticism and reliable and intelligent reporting, the government cannot govern. For there is no adequate way in which it can keep itself informed about what the people of the country are thinking, doing and wanting.

Similarly, through his weekly analysis in his column Peter Pan, he became reputed for bringing to the surface the hidden political and socioeconomic tension in the country that was already alive to where they could be seen and treated like a boil that can never be cured as long as it is covered up. But it must be opened with all its pus-flowing ugliness to the natural medicine of air and light; injustice must likewise be exposed to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.

To him, the function of the press was very high. It was almost holy. It serves as a forum for the people, through which the people may freely know what is going on. Enahoro believed that misstating or suppressing information is a breach of trust. To him, that was sacrosanct and pivotal for a development-oriented society.

However, while the world stands in awe for the late pen pusher because of his time-honoured understanding that the sole aim of journalism is service and in providing this service, one enjoys great power and followership, it remains a painful narrative that modern-day journalists have, unlike Mr Enahoro, used the same profession to communicate more hatred than love, injustice than justice and deprivation than equity.

Very regrettably, their use of the asymmetrical press in the country has brought about a state of affairs where tribal loyalty is now considered stronger and more important than our common sense of nationhood. In recent years, the press in Nigeria has become the stage for fierce political and ideological warfare in ways that negate our rationality as human beings.

Through the unfortunate process, a great amount of innocent human character has been spilt, wars of words waged, and countless souls/ambitions persecuted and martyred. The press has failed to communicate noble ideas and ideals. This consequence of their failures is responsible for why anarchy presently prevails in the country and accounts for why Nigerians daily diminish and are impoverished.

Also, presently in the country, media professionals, in their search for new but personal fields to increase their wealth and well-being, have opted out of its primary mandate of objective reportage to become a willing tool in the hands of these political gladiators.

While some have overtly become more cautious than courageous in performing their agenda-setting roles, others have on many occasions watched the making of political cum economic decisions that breeds poverty and perpetrates powerlessness, yet took the easy way out without addressing the underlying factors.

Curiously, media practice in Nigeria has seen power lately gone the wrong way but assumed it’s the right thing, I watched the nation’s political gladiators redefine democracy in the image of their actions but viewed it as normal.

And very oddly, unlike Mr Enahoro, who used media practice to promote nation-building and development, media professionals in the country presently no longer see themselves as problem solvers or watchdogs of the society but now occupy a high ground they do not understand while leaving the masses that initially depended on them confused.

As the world mourns this iconic writer who was a few days ago described as a national asset by the Edo State Governor, Mr Godwin Obaseki, it will be highly rewarding, in my view, if journalists in the country emulate his sterling virtues. That will be the best way to have him immortalized.

Adieu Peter Enahoro, the pen pusher!!!

Utomi is the Program Coordinator (Media and Politics), Advocacy for Social and Economic Justice (SEJA), Lagos. He can be reached via 08032725374

Feature/OPED

From Aid to Trade: Turning China’s Investment into Export Power

By Rachel Irvine

Africa may not boast the largest economies or deepest pockets, but it has what many regions lack: energy, youth, abundance, and innovation. While the rest of the world gets older and runs out of steam, Africa’s cities are expanding, consumer demand is rising, and resources remain plentiful.

What this means is that in the next 25 years, over half of global population growth will emanate from Africa, shifting the currents of investment, infrastructure, and trade.

Deep historic and cultural links are keeping the West engaged in Africa, but changing geopolitical dynamics are changing how its economic and strategic importance is viewed.

First mover advantage

Recognising its potential as a new frontier for global economic growth early on, China was Africa’s first meaningful investor in the 21st century. Over the past two decades, the Asian colossus has shifted its early focus on extractive industries to investing in renewable energy, railways, ports, manufacturing, digital networks, and healthcare. This commitment has helped lay much of the physical and digital backbone that Africa so desperately needs to grow.

Across the continent, projects backed by Chinese investment have strengthened critical systems and enabled new markets. The National ICT Backbone in Tanzania has expanded broadband access, made e-health and e-learning possible, and strengthened e-government services. In Sierra Leone, the China-Sierra Leone Friendship Hospital, built over 7,700m², continues to enhance healthcare delivery and played a vital role during the Ebola outbreak. The proposed $1.4 billion upgrade of the Tanzania-Zambia Railway furthermore promises to revitalise a key regional trade corridor for copper exports and improve transport efficiency in the region.

Such stories about local projects may not dominate headlines abroad, but they stimulate markets, build skills, and engender the conditions for African businesses and consumers to thrive.

A partnership evolving with the times

China’s approach has evolved to match Africa’s economic trajectory. The early years were defined by sovereign-backed megaprojects. Today, China invests in targeted, more manageable and commercially viable investments that encourage local participation and private-sector delivery while providing a clearer return on investment. This “small and beautiful” phase of its Belt and Road Initiative is well suited to Africa’s priorities: building industrial capacity, expanding renewable energy, and accelerating digital transformation.

The automotive sector offers a clear example. In South Africa, nearly half of the 14 Chinese car brands that are now active in the country, entered the market in the past year. BYD, one of China’s largest electric vehicle manufacturers, plans to triple its dealership network by 2026 and expand its range of electric and hybrid models. Other manufacturers, including Chery and Great Wall Motors, are gaining ground by offering technology-rich, competitively priced vehicles tailored for African consumers. These moves are about more than sales: they are building supply chains, creating jobs, and positioning South Africa as a hub for electric vehicle adoption and assembly.

Shifts in global trade are reinforcing these opportunities. As Western protectionism grows, including through US tariff regimes, China is expanding zero-tariff access for African goods and strengthening its role as a reliable trade partner. For African economies, this opens new markets and buffers against volatility in traditional export destinations.

Why engagement matters

For African governments, China’s role is pragmatic and strategic because it speeds up infrastructure delivery, broadens industrial bases, and opens new trade corridors. For businesses, aligning with this investment momentum can mean first-mover advantage in high-growth markets, improved access to logistics and industrial hubs tied into global supply chains, and opportunities to co-develop products and services for a rapidly expanding consumer base.

However, simply being present in the right markets is not enough. Success depends on positioning: showing a clear understanding of local priorities, demonstrating long-term commitment, and framing participation as part of Africa’s wider development story, which is why those that approach this relationship with clarity and purpose will gain both economic and reputational value.

This requires communicating the partnership in a way that resonates with audiences in both Africa and China – replacing outdated narratives of dependency with a focus on mutual benefit, shared priorities, and tangible results. Because perceptions can shift quickly and decisively, telling that story effectively is as critical as the investment itself.

Trade, not charity

Africa must be a partner, not a passive recipient of Chinese largesse by making African Continental Free Trade Area rules bite at the border, cutting clearance times, lifting product standards, and expanding export finance so manufacturers are able to deliver volumes. Manage debt in the open, and drop the tired “China asset grab” narrative, because outright takeovers are rare. The real work is negotiating clear, enforceable contracts that secure skills transfer and grow local capacity. The aim isn’t investment for show, but investment that builds competitive industries and export muscle. That’s how Chinese capital turns into jobs and exports.

Looking ahead

Africa’s annual infrastructure financing gap still exceeds $100 billion. No single partner can close it, but China’s willingness, scale, delivery capability, and track record make it an indispensable player in meeting that challenge.

For those who read the signs, the opportunities are boundless. The next decade will define the course of Africa’s growth and decide who reaps its rewards. Businesses, investors, and decision-makers who seize the opportunity – and position their willingness – will help to write Africa’s new story.

Rachel Irvine is the CEO of Irvine Partners

Feature/OPED

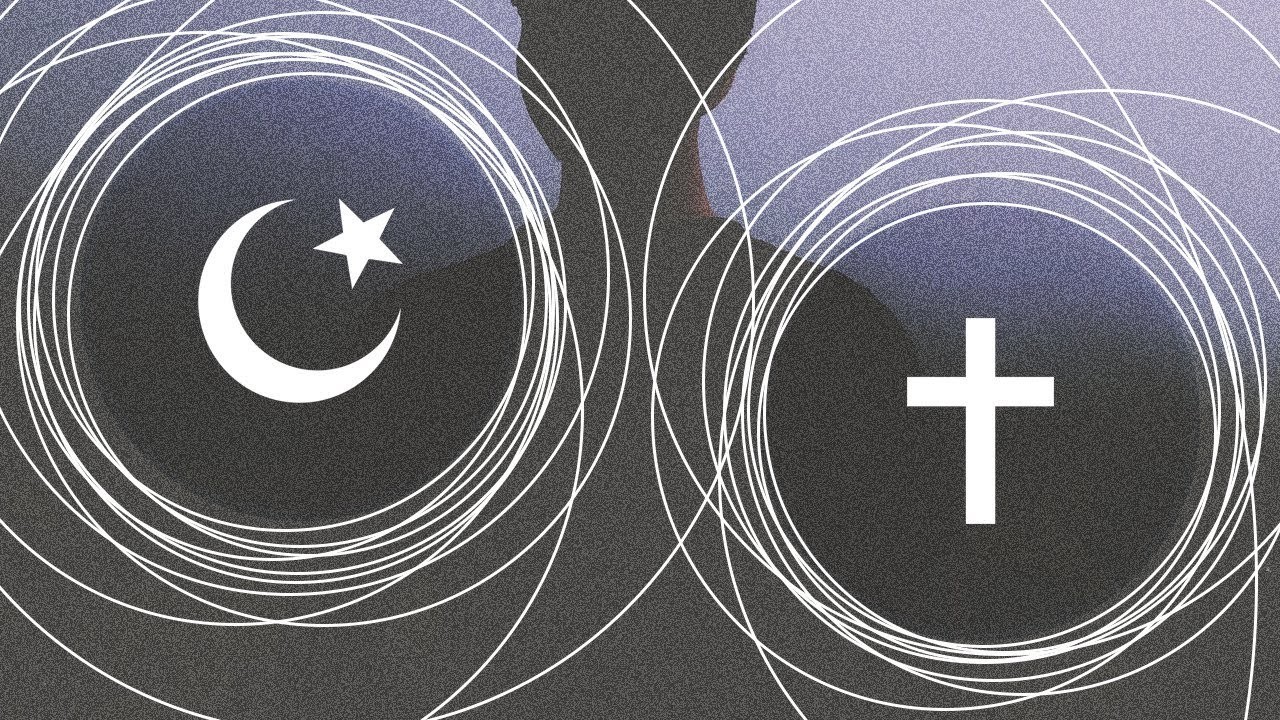

Nigerians and our Gods

By Prince Charles Dickson PhD

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, holds two remarkable distinctions: it has both the highest number of Muslims on the continent and the largest population of Christians as well.

Globally, Nigeria ranks among the top in both religions—boasting the sixth largest Christian population in the world and one of the largest concentrations of Muslims anywhere. By sheer numbers, Nigeria should represent a beacon of faith, morality, and godly example. Yet, the paradox remains: despite our crowded mosques and overflowing churches, our society is still riddled with corruption, injustice, insecurity, and a shocking contradiction between faith professed and life lived.

The Nigerian religious story is one of complexity—of gods old and new, of rituals that never quite disappear, and of a people who wear devotion on their lips but often defy it in their deeds. To speak of Nigerians and their gods is to enter the space where prayer meetings intersect with political thievery, where city streets turn into ghost towns on Fridays and Sundays, but where Monday mornings are marked by the hustle of swindling fellow citizens.

There is faith in numbers, decay in practice as by every measurable standard, Nigerians are religious. In almost every office, government meeting, and school gathering, prayers begin and end official functions. Even criminal gangs pray before embarking on their nefarious missions. We bless meals, recite scriptures, and fill radio waves with sermons. Mosques call the faithful five times daily; churches stretch services across the weekend with vigour.

But what has this avalanche of religiosity produced? Nigeria remains one of the most corrupt nations in the world. Governance is riddled with inflated contracts, missing billions, and leaders who mouth the name of God while looting public treasuries. A road project budgeted for billions of Naira is either abandoned or executed so poorly that it collapses within months. Who signs off these contracts? Who pockets the money? Are they not the same men and women who lead prayers, fund cathedrals, build mosques, and occupy front seats at religious ceremonies?

Here lies the great irony: our religiosity has not transformed our morality. In fact, it seems to have become a convenient mask—an outward cloak to conceal the rot within.

Christianity and Islam arrived in Nigeria centuries ago, bringing new texts, prophets, and doctrines. Yet, beneath the polished surfaces of imported faiths, older traditions remain alive. Nigerians still patronize voodoo priests, consult witch doctors, and invoke African magic in private moments of desperation. A politician may attend Sunday Mass in the morning and visit a shrine at midnight. An entrepreneur may recite Quranic verses but tie charms to his business doors.

This dual devotion—professed monotheism mixed with hidden polytheism—reveals a deeper struggle: Nigerians have not fully replaced their gods; they have simply expanded their pantheon. Faith in Allah or Christ often coexists with faith in ancestral spirits, diviners, and traditional sacrifices. In times of crisis, many revert to the old ways, seeking power or protection where modern religion and government have failed them.

Thus, religion in Nigeria becomes less a matter of deep conviction and more a utilitarian pursuit of survival, influence, or fortune. The gods, old or new, are reduced to instruments of power rather than anchors of virtue.

We suffer fanaticism and the burden of Extremes as despite the abundance of churches and mosques, freedom of religious belief remains fragile in Nigeria. From sectarian violence in the North to discriminatory practices in the South, religious tolerance is often preached but rarely practiced. Extremist groups, most notoriously Boko Haram, cloak their campaigns of terror in religious rhetoric, killing those who refuse to subscribe to their ideology.

Even within families and communities, interfaith marriages are frowned upon, and adherents of minority faiths face ostracism or persecution. Nigeria’s religious energy, rather than being harnessed for unity, often becomes combustible material for conflict.

We are left with a dangerous contradiction: a nation deeply religious, yet perpetually at war with itself in the name of religion.

Consider the everyday rituals of hypocrisy of Nigerian officialdom. A meeting begins with an opening prayer—sincere, perhaps, in tone—where God is invited to bless the deliberations. Discussions then follow, where decisions are taken to divert funds, inflate budgets, or marginalize certain groups. At the end, another prayer is offered, thanking God for “a successful meeting.”

In this ritual, God is both invoked and mocked. The prayer serves as a ceremonial cloak for systemic theft. Nigerian religiosity has perfected this cycle: sin boldly, pray loudly, repeat endlessly.

Our cities testify to this contradiction. On Fridays, streets empty as men and women flood mosques. On Sundays, roads are blocked by worshippers attending multiple services. Yet, by Monday morning, many of these same worshippers cannot wait to cheat their neighbour, manipulate figures, or exploit the system.

We profess to love God, but our love rarely extends to obeying His commands.

Here, the parable of the madman becomes instructive.

A wealthy man parks his expensive car, only to return and find that one of his tires is missing four bolts. Frustrated, he despairs until a madman suggests a simple solution: remove one bolt from each of the other three tires and use them to secure the fourth. Surprised by the brilliance of the idea, the man asks how someone “mad” could think so clearly. The madman replies: “I am mad, not stupid.”

This story is Nigeria’s mirror. We are a nation of wealthy resources, brilliant minds, and boundless faith. Yet, we often act foolishly, parading our religiosity without applying its wisdom. Like the rich man, we look helplessly at problems—corruption, bad roads, poverty, insecurity—while the solutions lie in plain sight. The madman’s lesson is that wisdom is not about appearance but application.

Nigeria’s religiosity is vast, but what we lack is the wisdom to apply the moral essence of our faiths. We build grand cathedrals and imposing mosques but fail to build integrity, justice, and love of neighbour. We perform rituals but neglect righteousness. We pray for prosperity but cheat our systems. We revere gods, but our gods—old and new—have not saved us because we have not lived their principles.

Yet, to be fair, not all Nigerians bow to this hypocrisy. Scattered across the nation are men and women who live by the tenets of their faith with integrity. The honest civil servant who resists bribes. The teacher who shows up every day in underfunded schools. The nurse who treats patients with dignity despite low pay. The entrepreneur who refuses to cheat his customers. The religious leader who preaches justice rather than prosperity.

These Nigerians—though often drowned in the noise of corruption and fanaticism—embody the hope of the nation. They prove that faith can indeed inspire virtue, that religion can transform society when applied with sincerity. They remind us that change will not come from prayers alone but from actions aligned with those prayers.

The problem, therefore, is not religion itself but the way Nigerians practice it. Our gods—whether Christ, Allah, or the spirits of our ancestors—are not to blame. The blame lies with us: we invoke their names without embodying their values. We exalt them in worship but abandon them in conduct.

If Nigeria is to rise from its contradictions, it must learn from the wisdom of the so-called madman: apply the principles already within reach. We must strip religion of its hypocrisy and return it to its essence—justice, mercy, love, and accountability.

A nation that prays at dawn but steals by noon cannot prosper. A people who fill mosques and churches but empty their institutions of integrity cannot progress. Nigerians must decide whether their gods are mere ornaments for ritual or guiding lights for life.

Until then, our religiosity will remain loud but hollow, plentiful but powerless. And like the man stranded by his car, we will continue to stare at problems, waiting for a madman to remind us that the solution has been in our hands all along—May Nigeria win!

Feature/OPED

Story of a Greener Future: Multichoice’s Journey to Renewable Energy and a 20% Carbon-Emission Cut by 2028

For more than three decades, MultiChoice has been known for telling Africa’s stories, from Nollywood to live sports and real-life documentaries. But today, it’s telling a different kind of story. One about the planet. One about the future. One where sustainability is the main character.

The world is at a turning point. Climate change is no longer a distant warning; it’s a daily reality. Businesses everywhere are rethinking how they operate, not just to protect the bottom line, but to protect the Earth itself. For MultiChoice, the shift feels natural. After all, improving lives through entertainment has always been at the heart of its mission. Now, that mission extends beyond screens into the air we breathe, the energy we consume, and the communities we serve.

At the centre of this transformation is a bold commitment: achieve carbon neutrality in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with a significant milestone of cutting emissions by 20% by 2028. It’s a journey that requires more than ambition; it demands action, innovation, and consistency. And so far, the results are encouraging. Between 2024 and 2025, the company reduced its Scope 1 carbon emissions by 25%, bringing the figure down to 19,483 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

Across its operations, changes are quietly reshaping the way the business runs. Motion-sensor lighting clicks on only when needed. Solar panels are powering offices and reducing reliance on the grid. Daylight-harvesting LED systems, energy-efficient inverters, and smarter heating, cooling, and ventilation systems are saving thousands of kilowatts.

Here in Nigeria, outdated chillers have been swapped for energy-efficient models, synchronising electric panels now ensures better power regulation, and solar installations are set to cut daytime electricity use by almost a third. Wastewater is treated and reused for landscaping, ensuring even the gardens tell a story of sustainability. In Ghana, powerful 44kV solar panels crown the MultiChoice Accra headquarters.

But MultiChoice’s sustainability journey isn’t confined to behind-the-scenes changes. The company is also using its greatest asset, its platform, to spark environmental awareness across Africa. Through its partnership with The Earthshot Prize, one of the world’s most prestigious environmental awards, MultiChoice shines a spotlight on innovators tackling some of the planet’s biggest challenges. This year, stories of African ingenuity, from plastic recycling to solar lighting and refrigeration innovations, reached up to five million viewers, generating 56 million Naira in media coverage and inspiring communities to think green.

John Ugbe, Chief Executive Officer at MultiChoice Nigeria, sums it up simply: “Our environmental efforts have picked up pace. We’re focused on shrinking our footprint and using our platforms to raise awareness around climate change.”

It’s this blend of internal change and public storytelling that makes MultiChoice’s approach unique. The company isn’t just cutting emissions; it’s weaving sustainability into Africa’s cultural conversation. And with the 2028 milestone in sight, the story is still unfolding.

“ESG isn’t a side project,” Ugbe says. “It’s part of who we are and will be in the future. It shapes how we work, how we innovate, and how we show up for Africa every day.”

This is not just the story of a greener future. It’s the story of how Africa’s most-loved storyteller is making sure the future is one worth telling.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism9 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking7 years ago

Banking7 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy2 years ago

Economy2 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking2 years ago

Banking2 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports2 years ago

Sports2 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn

-

Technology5 years ago

Technology5 years agoHow To Link Your MTN, Airtel, Glo, 9mobile Lines to NIN