Feature/OPED

Why 2026 Must Be the Year Nigeria’s Economy Works for All

By Blaise Udunze

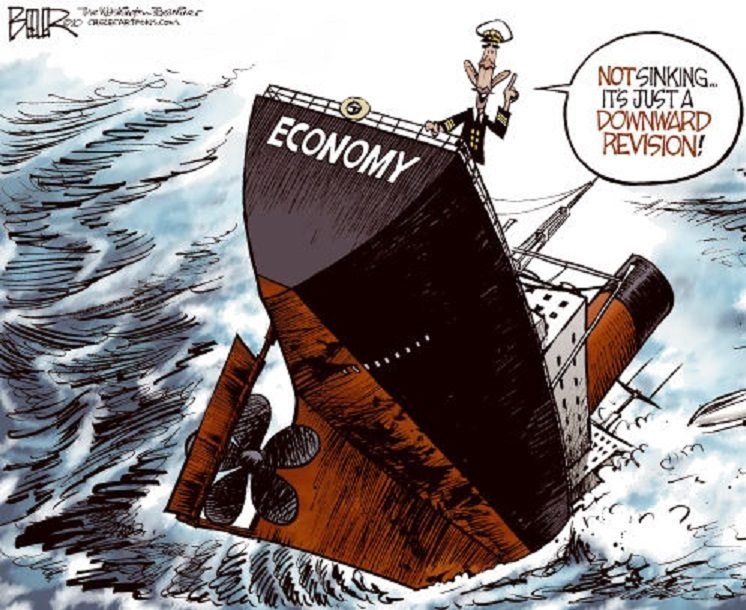

As the new economic year begins in Nigeria, statements and policies emanating from government officials’ corridors project cautious optimism. One of the official narratives that expresses renewal of hope and confidence is the projection from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) that the economy is expected to continue expanding, with GDP growth at 4.49 percent, and headline inflation is projected to moderate to 12.9 percent. Despite grappling with shrinking oil revenues, rising public debt, and widening fiscal deficits as a nation, it is further projected that the foreign reserves are anticipated to exceed $50 billion. Policymakers presented these figures as evidence that the economy is stabilising and consolidating, irrespective of the clear evidence of years of turbulence.

Yet the concern for experts is that beyond the polished macroeconomic indicators lies a widening disconnect between statistical recovery and lived reality. While increasingly warning that stability is necessary, the views across academia, civil society, labour groups, and the private sector, experts clearly stated that it is not synonymous with sustainable growth, nor does it automatically improve living standards for millions of Nigerians grappling with unemployment, rising prices, and fragile livelihoods.

This development signals the economic debate entering 2026, as evident in the previous years, the argument that the year must not become another chapter in which rhetoric outpaces results. To them, it must place productivity, inclusion, and welfare at the heart of reform as all this must be informed via a decisive shift toward holistic, people-centered economic renewal.

The Numbers and the Narrative

There is no denying that certain macroeconomic indicators have improved. Tighter monetary policy in 2025, foreign exchange market unification, and efforts to rein in deficit financing have contributed to relative stability in inflation dynamics and exchange rate volatility.

However, economists interviewed by major national dailies argue that many of these gains remain largely “on paper.” They clearly stated that growth figures have not translated into broad-based job creation, rising real incomes, or improved business conditions for small enterprises. It is regrettable that households whose spending is dominated by food, transport, and energy, whilst inflation. However, easing remains painfully high relative to income, and this disconnect underscores a deeper flaw in economic communication and design, showing that headline indicators often mask structural weaknesses. GDP growth does not automatically reflect productivity expansion, employment quality, or resilience. Foreign reserves alone do not guarantee the affordability of necessities. When policy emphasis centres on aggregates rather than outcomes, reform risks losing social legitimacy.

When Stability Isn’t Enough

The inflation debate illustrates this dilemma clearly, and projections suggest moderation in 2026, yet prices of essential goods remain high. Low-income households, especially those outside formal wage employment, bear a disproportionate burden. For them, “disinflation” offers little relief when purchasing power has already been eroded. In like manner, exchange rate unification, though economically rational, imposed short-term shocks on import-dependent businesses and consumers. The fact remains that without a simultaneous and aggressive push to strengthen domestic production, the nation’s currency reforms risk transferring adjustment costs to households rather than building long-term competitiveness. These debates reveal two competing visions of economic management:

– One that prioritises macroeconomic order and investor confidence

– Another that insists stability must be matched by visible improvements in welfare, productivity, and opportunity.

The fact is that a holistic renewal agenda must reconcile both.

Macroeconomic Stability as Foundation, Not Destination

To be clear, stability matters, and it must be treated as a foundation, not the finish line. One will conclude that this is what it is meant to be because economic planning becomes impossible without disciplined fiscal management, credible monetary policy, and sustainable debt dynamics. Experts caution against celebrating stabilisation while growth remains modest.

The International Monetary Fund projects Nigeria’s growth to slow toward three per cent, with further moderation in 2026 due largely to weaker global demand and declining oil prices. Crude oil’s fall below Nigeria’s budget benchmark reinforces the urgency of diversification. Moderate growth, without deep structural reform, cannot absorb Nigeria’s rapidly expanding labour force. This is because as a young, fast-growing population requires productivity-led growth, not cyclical rebounds tied to commodity prices.

Infrastructure as the Productivity Multiplier

Infrastructure remains one of Nigeria’s most binding constraints, commonly associated with the lingering erratic power supply, congested transport corridors, inefficient ports, and weak digital connectivity, which impose high costs on businesses and households alike.

Consistently, it is argued by experts that fragmented projects are insufficient by objectively looking at the trend of things; what is required is integrated infrastructure planning that links energy reform with transport logistics, industrial clusters, rural access roads, and digital platforms. Some of the key grey areas that the electricity reform must address are not just generation but transmission losses, distribution inefficiencies, and tariff credibility. Without much ado, transport investments should prioritise economic corridors and channels that connect farms to markets and factories to ports. Digital infrastructure, broadband access, data systems, and digital public services must be recognised as essential economic infrastructure, not optional upgrades.

Human Capital and the Missing Engine of Growth

No economy can sustainably outgrow the quality of its people. Yet education and healthcare often remain peripheral in reform discourse.

Today, we noticed that Nigeria’s education system struggles with skill mismatches, while healthcare costs push millions into poverty.

Economic growth, no matter how well-measured, will remain shallow, as experts have maintained in their arguments that this will remain a constant factor without human capital reform. In the same manner, education, which is a key instrument for building human capital, must be in alignment with labour-market needs, while reflecting technical skills, digital literacy, and adaptability, knowing quite well that vocational and technical are critical and should be elevated as engines of productivity, not treated as second-tier options. Human capital is not social expenditure; it is economic investment, so for this reason, healthcare investment, like others, must prioritise preventive care, insurance coverage, and workforce retention.

Private Sector and MSMEs, From Constraint to Catalyst

Small and medium-sized enterprises are already struggling to survive in Nigeria’s high-cost economy, despite being the nation’s largest employer of labour, as informed by high interest rates, limited credit access, regulatory uncertainty, and infrastructure bottlenecks.

Access to affordable finance, regulatory simplicity, predictable tax policy, and contract enforcement are critical since experts repeatedly stress that reform must shift from controlling enterprise to enabling it.

Without deliberate support for small businesses, growth remains concentrated, informal employment persists, and inequality deepens. For these reasons, MSMEs require not just credit, but stable operating environments.

Industrialisation, Local Production, and Value Addition

One of the strongest expert warnings ahead of 2026 concerns Nigeria’s continued reliance on imports and raw commodity exports. This structure leaves the economy exposed to external shocks and foreign exchange volatility. For this reason, we have continued to witness economists and industry leaders advocating aggressive support for local production, agro-processing, and manufacturing value chains. Strengthening domestic capacity reduces import dependence, stabilises foreign exchange demand, and creates jobs.

Industrial policy must practically focus on sectors where Nigeria has a comparative advantage, supported by infrastructure, skills, and finance. This is to say that import substitution without competitiveness risks inefficiency, and value addition with productivity creates resilience.

Fiscal Reform and Social Justice

Fiscal reform is very important, and experts have argued that to make sure that fiscal reform is done in a fair way, it must be equitable. The tax officials must ensure that extending the tax base, it does not translate into overburdening small businesses or low-income earners. Also, one would have noticed that the removal of fuel subsidies freed fiscal space, but without strong social safety nets, it also made life very tough for a lot of people because they did not have any help when they needed it. Critics argue that reform savings must be visibly social investments like education, healthcare, transport, and targeted welfare. Social protection is not charity; it is economic stabilisation, preventing reform shocks from eroding social cohesion.

Governance, Institutions, and Policy Credibility

Unique to the Nigerian system, we have witnessed economic reforms fail where institutions are weak. This is because trust and investment have been undermined due to Policy reversals, regulatory inconsistency, and the lack of transparent decision-making.

Beyond rhetoric to enforcement, experts emphasise the need for policy coherence, institutional professionalism, and transparent communication. Anti-corruption efforts must extend. Prolonged Judicial judgement, particularly in commercial dispute resolution, has adversely impeded the smooth running of society as it questions the credibility of the system. Good governance is not abstract morality, rather it is a growth multiplier.

Agriculture, Food Security, and Rural Stability

Food inflation remains a major driver of hardship and has been one of Nigeria’s most stubborn. Though trade liberalisation has occasionally eased prices, experts argue that without boosting domestic agricultural productivity, food security will remain fragile.

Mechanisation, storage infrastructure, rural roads, insurance, and access to finance are essential. Equally critical is addressing rural insecurity, which disrupts production and inflates food prices.

Agriculture links economic growth directly to poverty reduction and social stability.

Digital Economy and Innovation

Technology is no longer a sector; it is a layer across all sectors. One can argue that Nigeria’s fintech success demonstrates what is possible, but looking at it intently, a broader digital transformation requires investment in connectivity, data protection, and cybersecurity. Regulation must be enabling, must be able to change when necessary, and forward-looking to achieve a thriving digital economy that can generate jobs, improve service delivery, and connect local firms to global markets.

The Productivity Challenge in Decline

Across expert critiques, one theme recurs: stability without productivity is stagnation.

An economy can be stable yet unproductive, grow slowly, create little or no jobs, and remain vulnerable to shocks. Productivity growth transforms stability into prosperity. It requires investment in people, infrastructure, innovation, and institutions.

Without productivity, growth becomes cyclical, driven by oil prices, not by domestic capacity.

From Rhetoric to Resonance: Closing the Credibility Gap

As Nigeria enters 2026, it has to choose to either settle for modest stability and make progress or pursue bold, people-centred strategies that generate shared prosperity.

The signs of stabilisation are real. But so is the urgency for deeper reforms that trickles down to the daily lives of those at the lower rung. Growth must be measured not only in GDP figures, inflation rates, or reserves, but in the number of jobs that are being created, the people who are earning money, and the businesses that are still running, with hope restored. It is expected that a true economic renewal in 2026 will not be announced; it will be felt.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

Feature/OPED

Another Oil Boom: Will Nigeria’s Government Turn Windfall into Growth or Squander it?

By Blaise Udunze

The past recurring conflicts on other continents and the current developments in the Middle East are a clear reminder to the world that energy markets are deeply linked to conflict and uncertainty, as experienced across the globe today. The rise in geopolitical tensions with Iran, Israel, and the United States has led to a sudden increase in global crude oil prices. Some individuals may question what business the war has with Nigeria. Economically, yes, as one of Africa’s major oil producers, Nigeria finds itself in a delicate position amid the current global situation. Since it can gain financially when global crude oil prices skyrocket and this is so because the same increase can create economic challenges locally. The price of Brent crude has jumped to $109.18 per barrel, crossing the $100 mark for the first time in more than five years.

The country is getting a temporary fiscal boost, knowing fully well that prices now surpass the benchmark used in the 2026 national budget. The high oil prices gain is further amplified by two major domestic policy shifts, as the first is the removal of fuel subsidy projected to free nearly $10 billion annually for public investment, and a new Executive Order by President Bola Tinubu aimed at boosting oil and gas revenues flowing into the Federation Account by eliminating wasteful deductions allowed under the Petroleum Industry Act. The combination of these developments could significantly increase government revenue over the next few years, but history shows that such windfalls, if not well managed, often go toward short-term spending rather than creating lasting national wealth.

Moreover, our lingering concern today is that Nigeria as a country has experienced this pattern before, and it often brings instability. One of such examples is the 2022 Ukraine conflict, when oil prices spiked above $100 per barrel.

Obviously, during such a period, countries that export oil will suddenly receive a large and sudden increase in revenue from the sale of crude oil. The truth is that if such a windfall is managed well, it can be used to build stronger and diversify their economies beyond oil. Unfortunately, Nigeria has always told a different story as these opportunities were frequently lost to weak fiscal discipline, rising recurrent expenditure, and limited investment in productive assets. The global conflict, in its real sense, could become an opportunity, even though there are risks inherent. Just like any prudent country, Nigeria can use any short-term benefits (like higher oil revenues) to strengthen its economy for the future.

At the heart of this opportunity lies the need for disciplined fiscal management, if the government will tread in line with this call. It is now time for the policymakers to understand that extra money from oil prices should not be wasted, as it has become a tradition to spend through the regular government expenditures. It is high time the government saved and invested the extra funds it gained wisely rather than spending them all immediately. Nigeria’s fiscal vulnerability has often been exposed whenever oil prices fall or global demand weakens. Establishing strong buffers through sovereign savings mechanisms can protect against such volatility. A significant portion of the windfall should therefore be directed into strengthening the country’s sovereign wealth structures and stabilisation funds. This resonates with our subject matter: Can Nigeria convert Oil Windfall into Economic Strength? This rhetorical question is directed to those at the helm of affairs because, by saving during periods of high prices, Nigeria can build reserves that help sustain public spending during downturns without excessive borrowing.

Closely linked to fiscal buffers is the issue of public debt. Nigeria’s debt servicing obligations have continued to rise in recent years, and the current development might be the answer. The debt has continued to place pressure on government revenues and limit fiscal flexibility. Alarming is the fact that the public debt is projected to have surpassed N177.14 trillion by the end of 2026, which is driven by the budget deficit in the 2026 Appropriation Bill.

The truth is that one sensible response to the current situation would be to use some of the unexpected revenue from higher oil prices to pay off loans (debts), especially those with high interest costs. This would reduce future financial burdens on the government and help it spend on development later. The fact is that debt reduction, if the government can quickly address it, also signals fiscal credibility to investors and international financial institutions, thereby strengthening the country’s macroeconomic reputation.

Beyond fiscal stability, Nigeria must recognise that oil windfalls provide a rare opportunity to accelerate strategic infrastructure investment. In today’s world, infrastructure remains one of the most critical constraints on Nigeria’s economic growth. The cost of doing business in Nigeria has been a serious palaver, and it has continued to discourage and scare investment. This is informed by various structural deficiencies, such as inadequate electricity supply and congested transport corridors, as well as weak logistics networks. The question again, can Nigeria convert Oil Windfall into Economic Strength? This is because the truth is not unknown to leaders, but they have continued to deliberately stay away from the fact that channelling windfall revenues into transformative infrastructure projects can therefore yield long-term economic dividends.

Power sector development should be a top priority. Reliable electricity remains the backbone of industrial productivity and economic expansion. Over the years, a well-known fact is that despite various reforms, Nigeria continues to struggle with an epileptic power supply that forces businesses to rely heavily on expensive diesel generators and has posed a double challenge that comes with noise and atmospheric pollution. The nation is tired of the regular audio investment, but strategic investment in power generation, transmission, and distribution infrastructure would significantly reduce operating costs for businesses that translate into manufacturing and encourage new investment across multiple sectors in the country.

Transportation infrastructure also deserves sustained attention, and if nothing is done, the mass commuters will reap nothing but pain. Nigeria’s highways, rail networks, and ports require large-scale modernisation to support efficient trade and mobility. The unexpected extra income from high oil prices, if used carefully for long-term national benefit, can be used to build transport networks that move food and goods from farms and factories to markets and ports. Businesses today are very much dependent on transportation; hence, improved logistics not only facilitates domestic commerce but also strengthens Nigeria’s position as a regional economic hub in West Africa.

Another critical area for deploying oil windfalls is economic diversification. The over-emphasised dependence of Nigeria on crude oil exports has long exposed the economy to external shocks.

Any rise or fall in global oil prices has an immediate impact on Nigeria’s government revenue since oil exports are a major source of government income, foreign exchange availability, and macroeconomic stability follow suit. To break this cycle, Nigeria must invest aggressively in sectors capable of generating sustainable non-oil income and abstain from the unyielding roundtable discussion of diversification without implementation.

With vast arable land and a large labour force, Nigeria has the capacity to become a global agricultural powerhouse; hence, this is to say that agriculture offers enormous potential in this regard. However, productivity remains constrained by limited mechanisation, inadequate irrigation, and poor storage facilities. If the government intentionally invests in modern agriculture and the systems that support it, the country can produce more food, create jobs via agricultural value chains (from production to processing, storage, transportation, and marketing), while earning more from agricultural exporting.

Manufacturing and industrial development represent another pathway to long-term economic resilience, but this sector has been starved of any tangible investment. Unlike Nigeria, countries that successfully convert natural resource wealth into sustainable prosperity typically invest heavily in industrial capacity. The government should be deliberate in using the extra revenues from the high oil prices to invest in building industrial zones, strengthening hubs, and encouraging the transfer of technologies that will fast-track the production of goods within Nigeria, instead of relying on imports. The unarguable point is that the moment Nigeria invests in industries and production of goods locally instead of buying them from other countries, it becomes better able to manufacture and export products that have higher economic value.

One critical aspect that calls for concern is that strengthening Nigeria’s foreign exchange reserves represents another important avenue for deploying excess oil revenues. The truth, which applies to every economy, is that adequate reserves enhance the country’s ability to stabilise its currency during external shocks and support the operations of the Central Bank of Nigeria in maintaining monetary stability, and this part must not be treated with kid gloves. Given Nigeria’s history of foreign exchange volatility, this is another opportunity to know that building strong reserves can significantly improve investor confidence and macroeconomic resilience.

Human capital development must also remain central to any long-term strategy for managing oil windfalls. A country’s greatest asset is not merely its natural resources but the productivity and innovation of its people, and in Nigeria, more attention has been placed on the former. For so long, Nigeria’s budget allocation has told this story, as the government has been glaringly complacent in investing in quality education, healthcare systems, technical training, and research institutions, which can unlock enormous economic potential. If the government aligns with the necessities, Nigeria’s youthful population represents a demographic advantage that can only be realised through sustained investment in human development.

Investment from the higher oil prices should be channelled to the educational sector, and more emphasis should be placed on science, technology, engineering, and vocational skills that align with the demands of a modern economy. Strengthening universities, technical institutes, and research centres can foster innovation, entrepreneurship, and technological advancement. Similarly, improving healthcare infrastructure enhances workforce productivity and reduces the economic burden of disease. Will the government ever shift reasonable investment to these sectors?

Another strategic use of all the categorised oil windfalls is the expansion of social protection systems that shield vulnerable populations during economic shocks. What is unbeknownst to the government is that while infrastructure and industrial investments drive long-term growth, social protection programs help ensure that economic gains are broadly shared. Helping the poor, creating jobs for young people, and supporting small businesses can make society more stable and grow the economy from the ground up.

Lack of transparency and accountability has been anathema that has hindered the progress of growth in Nigeria. The right implementation will ultimately determine whether Nigeria successfully transforms this oil windfall into lasting prosperity. Public trust in government fiscal management has often been undermined by corruption, waste, and non-transparent financial practices. Once there are clear frameworks for managing windfall revenues, this becomes essential. Also, if it is monitored by neutral institutions that are not controlled by politicians, while information about spending is made available to the populace, the media, and the National Assembly supervises how the funds are spent, it will translate to what benefits the country instead of short-term political interest.

A section of the economy that calls for action is the need to improve the efficiency of government institution capacity within agencies responsible for revenue management, budgeting, and project execution. It is a well-known fact that when government institutions are strong and effective, public money is less likely to be wasted, stolen, or misused, and investments produce measurable economic outcomes. This institutional strengthening should include digital financial systems, procurement transparency, and improved project monitoring mechanisms.

Nigeria’s policymakers must immediately put in place clear fiscal rules governing the use of oil windfalls. This will help define how excess revenues are distributed between savings, infrastructure investment, debt reduction, and social programs, and this will also help Nigeria prevent the politically driven spending patterns that have historically undermined effective resource management.

Another question confronting Nigeria is not whether oil prices will rise again in the future, but whether the country will finally break the cycle of squandered windfalls. It is to the country’s advantage that the current crisis has pushed oil prices above the budget benchmark, creating a temporary revenue advantage, but it must be noted that temporary advantages become transformative only when they are guided by deliberate policy choices and long-term vision.

Nigeria possesses immense economic potential. With a large domestic market, abundant natural resources, and a vibrant entrepreneurial population, the country is well-positioned to achieve sustained growth. This potential requires disciplined management of national wealth, particularly during periods of resource windfalls.

The common saying that a word is enough for the wise is directed to policymakers to understand that, if managed wisely, the current surge in oil revenues could strengthen fiscal buffers, modernise infrastructure, diversify the economy, and invest in human capital. The obvious here is that the investments would not only protect Nigeria against future oil price volatility but also lay the foundation for a more resilient and prosperous economy.

The lesson from global experience, as it has always been, is that resource windfalls do not automatically translate into national prosperity. Nigeria’s leaders must understand that, without exception, countries that succeed are those that convert temporary commodity gains into permanent economic assets. Nigeria now stands at such an intersection, which requires turning crisis-driven oil gains into strategic investments; the nation can transform a moment of geopolitical turbulence into an opportunity for lasting economic resilience and national wealth.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

Feature/OPED

From Presence to Power: Building The Table We Deserve

By Marieme-Sav SOW

Often, I am the only woman in the room – sometimes, the only African woman.

This is not a complaint, but a statement of fact. It is my starting point, and it has offered me an unexpected advantage: being the only one sharpens your awareness. You notice what others overlook.

Early in my career, I believed that dedication and results alone would be enough to transform this industry. But I have since realized that progress demands more than just individual determination -it requires intentional, collective action. Years later, the landscape has shifted: more women attend conferences, more enter junior roles, and more appear in the photos that fill diversity reports. Yet in the rooms where real decisions are made, silence persists. Those spaces remain emptier – and quieter – than they should be. So yes, frankly, I’m weary of watching women’s day celebrations substitute for change.

In my industry, this matters even further because energy is not just about pipelines and power. Energy is about who gets light, who gets jobs, who gets opportunity. When half the population is absent from those decisions, we build systems that serve everyone imperfectly. I witnessed the impact of this firsthand.

In Uganda, a family was being compensated for property affected by a project. The husband spoke; the wife listened. But when asked about the family’s needs, about what “fair compensation” really meant, it was the wife who had the answers. She knew what the household required. She knew who in the community would be affected. She knew because she lived it every day.

That moment changed how I think about influence.

But influence is also about who leads projects, who manages budgets, and who sits on executive committees. In Mozambique, I witnessed a mid-level engineer – a woman – identify a technical flaw that had eluded everyone else. She spoke up, her voice calm yet unmistakably authoritative. The room listened. The plan changed. That, too, is influence. It happens when women are not merely present but empowered to challenge, question, and correct.

At TotalEnergies, I have seen what happens when we design for that kind of influence. In our Tilenga and EACOP projects, compensation requires both spouses’ signatures. Joint bank accounts are mandatory. Financial literacy training reaches both partners. These are small shifts with enormous impact. They work because they recognize that women deserve more than just a place at the table.

In our affiliate in Nigeria, important strides have been made in recent years with intentional diverse hiring practices. As a result, over half of the senior roles filled between 2022 and 2024 went to women. This wasn’t the result of quotas, but of deliberate investment in talent pipelines that made such progress possible, proof that when influence is shared, outcomes improve.

This is what I carry into every boardroom. Not frustration at being the only woman, but a quiet responsibility. To notice what others might not. To ask questions that need to be asked. To ensure that the next generation of African women in this industry has more than a seat. They have influence.

But real influence requires a shared commitment. I urge women: seek out opportunities, develop new skills, and step boldly into leadership. I call on companies: create mentorship, training, and policies that allow women to grow and lead. Together, let us actively enable women to drive innovation and guide the future of energy.

The energy transition underway in Africa is the most profound economic shift of our lifetime. It will determine who prospers and who struggles for generations. We must act now – women must claim their voices and roles in this transition. If we do not, we risk building an energy future as unequal as in the past.

I believe we can do better.

So, I will keep walking into those rooms. I will keep learning from the women I meet along the way. I will give to gain, and I will keep pushing for the kind of deliberate design that turns mere presence into power.

As we mark this month dedicated to the fight for women’s rights everywhere, the goal is not simply more women at the table. The goal is to build the table we deserve.

Marieme-Sav Sow is a Senegalese energy executive, currently VP for Engagement & Advocacy for TotalEnergies EP Africa. A trailblazer, she served as Managing Director in Madagascar and made history as the first woman president of the National Petroleum Association (GPM). A vocal advocate for gender equality and workplace diversity, Marieme-Sav has received numerous recognitions for her leadership, including Africa’s Top 50 Women in Management and the Woman CEO of the Year awards.

Feature/OPED

HerStory in the Making: How Africa Magic is Celebrating Women All March Long

Every year, March arrives with a reminder of just how powerful, resilient, and extraordinary women are. With International Women’s Day anchoring the 8th of March, the entire month has come to be celebrated across the globe as Women’s Month, a time to honour female voices, amplify their stories, and reflect on the journeys that have shaped history.

This year, Africa Magic on GOtv is not just marking the occasion; it’s making a statement. Through a curated lineup of compelling films airing all through March, Africa Magic is dedicating its screens to stories that centre women: their strength, their sacrifices, their secrets, and their survival. The theme? HerStory in the Making.

From tales of mothers fighting to protect their families, to women reclaiming their power after abuse, to fierce rivalries driven by love and jealousy, these are the stories that reflect real life, real womanhood, and real Africa. Here’s a look at what’s showing on Africa Magic this month.

Heartline: Heartline touches on one of love’s oldest truths, that a woman’s presence can quietly dismantle even the most calculated of plans. Heartline follows the journey of a man who arrived with an agenda, a deceptive plot already in motion, and every intention of seeing it through. He didn’t leave the same. What unfolds is something neither he nor you will see coming. There’s just something about the way this story moves that reminds you how effortlessly a woman can change the room, change the plan, and change a man, simply by being herself. Catch Heartline on Saturday, March 7 at 7 pm on Africa Magic Showcase (GOtv Channel 8).

Ashes to Beauty: Ashes to Beauty is the kind of story that hits close to home. It explores the impossible weight mothers carry, the need to be everything, protect everything, and appear as though none of it costs them anything. For this mother, the image was everything: the perfect home, the perfect family, the life she had carefully curated and prayed over. Then a scandal arrives and threatens to burn all of it to the ground. Faced with an impossible decision, she must choose between preserving her image or confronting the truth, no matter the consequences.

This movie is raw and deeply emotional. Watch Ashes to Beauty on Sunday, March 8, at 9 pm on Africa Magic Showcase (GOtv Channel 8).

Love and Friendship: Love and Friendship explores a complicated question many women quietly face: what happens when survival finally gives way to the possibility of love?

After leaving an abusive marriage, Nonye seeks refuge with her closest friend, Somkele, hoping only for peace and a fresh start for herself and her daughter. But when unexpected feelings begin to develop between Nonye and the man Somkele loves, their friendship is suddenly placed in a fragile position. It’s a tender and layered story about loyalty, healing, and the complicated nature of love. Tune in on Saturday, March 7, at 9 pm on Africa Magic Family (GOtv Channel 7).

Emi Nikan: Emi Nikan is a fascinating look at what happens when the structures holding a home together are finally seen for what they are. When circumstances force a proud man to depend on his wife, to step back and let her lead, everything he thought he knew about himself begins to crack. She was always the foundation. He just didn’t know it yet. But as roles reverse and pride gives way, something darker begins to surface beneath the surface of their marriage, a secret that changes everything. This film quietly makes its point: some women have been carrying the weight all along. We just weren’t watching closely enough.

Watch Emi Nikan on Sunday, March 8, at 5:45 pm on Africa Magic Yoruba (GOtv Channel 2).

Thirty and Eligible: Thirty and Eligible is the romantic comedy that feels like it was written about someone you know, maybe even you. Two people in their thirties, both quietly terrified of commitment, stumble into each other and feel something neither was prepared for. So naturally, they both disappear. When the universe pushes them back together, they try to keep it simple, a no-strings arrangement, no feelings, no complications. It works perfectly. Until it doesn’t. Funny, warm, and honest about the very specific chaos of figuring out what you actually want versus what you’ve been telling yourself you want, this one’s for every woman who has ever talked herself out of something wonderful. Watch it on Saturday, March 14 at 7 pm on Africa Magic Showcase (GOtv Channel 8).

With a lineup that cuts across drama, romance, and comedy, March on Africa Magic promises something for every kind of viewer. Whether you’re in the mood for a story that keeps you guessing or one that simply makes you smile, there’s plenty to look forward to on screen this month.

To subscribe, upgrade, or reconnect, download the MyGOtv App or dial *288#. You can also stream anytime with the GOtv Stream App.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn