Jobs/Appointments

Damages Recoverable for Wrongful Dismissal

By Benita Ayo

It is to be expected in every human relations for conflict to arise. By its nature, the relationship between an employer and the employee is contractual and thus, any breach of the terms of contract is treated as a fundamental breach to which the aggrieved party will be entitled to damages.

The relationship between the employer and the employee is often governed by the contract existing between them stating various terms relating to the relationship.

Termination versus Dismissal: Differences in Between

While termination is bringing to an end to something, dismissal is the act of ordering or allowing someone to leave.

In light of the above, the differences between these two is that in the first situation (Termination), a party is merely exercising his rights in an agreement regulating the relationship and the affected party has a say in how the right is exercised. It is bringing the contract of employment to an end after giving the required notice or payment in lieu of notice. Termination is a mutual decision. In this case, the employee is entitled to payment of benefits.

In the case of dismissal, the employer simply removes the employee without any notice given or payment in lieu of notice.

The court has made some distinction between these two in the case of SEVEN UP BOTTLING COMPANY PLC v. AUGUSTUS (2012) LPELR-20873 where it held thus “It is trite that “dismissal” of an employee by the employer translates into bringing the employment to an end while under “termination of appointment”, the employee is enabled to receive the terminal benefits under the contract of employment. The right to “terminate” or bring an employment to an end is mutual in that either party may exercise it. “Dismissal” on the other hand is punitive and depending on the contract of employment entails a loss of terminal benefits. It also carries an unflattering opprobrium to the employee.”

From the above authority, the differences between termination and dismissal are;

Termination is a right exercisable under a contract of employment and it is a mutual decision while dismissal is a punitive measure for the wrongful conduct of the employee.

Where a reason is given for bringing the relationship to an end, this will amount to dismissal but where a reason for bringing the relationship to end is not given then this will amount to termination.

An employee is not entitled to receive terminal benefits where he is dismissed but he is entitled to such benefits where the employment relationship is terminated.

Notice or payment in lieu of notice is given to the affected employee in the case of termination. This is not the situation with dismissal.

Elements of Termination and Dismissal

The element(s) of termination and dismissal include;

Termination

Explanation for disengagement is not required

A month notice or payment of one month salary in lieu of notice is required

The disengaged staff is entitled to terminal benefits

Dismissal

Reason for disengagement must be given

A month notice or payment of one month salary in lieu of notice is not require

In most cases, the dismissed staff is not entitled to terminal benefits

The dismissed staff must be confronted with the allegations against him, accorded fair hearing and be made to appear before a panel before sanction.

Damages Applicable to Wrongful Termination

The damages applicable to wrongful termination is that the Claimant becomes entitled to the salary and other entitlements already lawfully accruable. This covers the period within which the employer would have lawfully terminated the contract of employment.

In the case of OSISANYA v. AFRIBANK (NIG) PLC (2007) 6 NWLR (PT. 1031) @586 PARAS. D-E (SC), the Appellant was an employee of the Respondent. Two individuals alleged that the appellant had committed some dishonest acts in the course of his duties under the respondent. In consequence, the appellant was suspended from work.

However, those who wrote the petition later withdrew it. That appeared that the petition had been motivated by malice. The appellant’s expectation that he would be recalled from suspension following the withdrawal of the petition did not materialize.

Rather, the appellant by a letter dated 12/10/87 was summarily dismissed from the respondent’s employment.

Consequent upon his dismissal, the appellant filed an action at the High Court against the respondent claiming, amongst others, a declaration that his dismissal from the services of the respondent was wrongful, unlawful and unconstitutional and some other reliefs.

Alternatively, the appellant claimed from the respondent the sum of ₦176,602.00 (One Hundred and seventy-six thousand, six hundred naira only) being special damages for his wrongful dismissal from the services of the respondent.

The trial court, after hearing both parties, granted a substantial part of the appellant’s reliefs and held that the appellant was deemed to be in the respondent’s employment till 14/10/96 which was the date judgment was delivered.

It equally held that the appellant’s employment with the respondent was to be determined from the next day by payment to him a month’s salary in lieu of notice. The respondent’s appeal to the court of Appeal was allowed.

The court of Appeal in setting aside the judgment of the trial court held that the appellant was to be paid all his salaries and entitlements up to 12th October, 1987, the date of dismissal and thereafter a month’s salary in lieu of notice. Dissatisfied with the decision of the court of Appeal, the appellant appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court adopted the two issues formulated by the respondent as follows:

Having regard to the lower court’s decision that the dismissal of the appellant by the respondent was wrong was the court right in awarding him one month’s salary in lieu of notice and his salaries and entitlements up to the date of his wrongful dismissal.

Could the dismissal or termination of the appellant from the employment of the respondent affect his privileges, rights, benefits and status as a shareholder in the respondent’s company in view of the provisions of the Companies and Allied Matters Act.”

In the final analysis, the Supreme Court held that the appeal had no merit. It was thus accordingly dismissed.

In its pronouncements, the court stated that “In a master/servant relationship, the damages available to the employee is the payment of his salary and other entitlements already lawfully accruable and payable for the period for which the employee should have been given notice of termination. The damages will be the amount he would have earned if his employment was properly and validly determined………..” PER OGBUAGU, J.S.C.

The above position was also emphasized in the case of 7UP BOTTLING COMPANY PLC v. ANYANYAAFAM AUGUSTUS (2012) LPELR-20873 (CA), the Respondent, until the month of October 2002 was an employee of the Appellant company and worked in the Appellant’s Accounts Department.

Sometimes in the month of August 2002, it was alleged that the respondent had fallen short of the standard required of his office when he fraudulently made two payments of ₦30,000.00 to one Mr O. E. Nwosu (Secretary to the Marketing Manager of the Appellant’s company) on the 5th and 6th days of August 2002, respectively which the respondent denied.

A query was issued to the respondent by the appellant and he answered it. The appellant through its accounts Manager set up a panel to further investigate the allegation. The investigation revealed that the respondent was innocent of the allegation.

However, the appellant through its Personnel Manager, Mr. Kiki Ebube, terminated the employment of the respondent. The respondent was not happy with the termination of his employment. He, by a writ of summons and statement of claim, claimed against the appellant as follows;

A declaration of the Honourable court that the purported termination of the plaintiff’s employment by the defendant through its Personnel Manager Kiki Ebube is vexatious, unlawful, null and void and of no effect whatsoever.

₦250,000,000.00 (Two Hundred and Fifty Million Naira) special and general damages for the unlawful termination of the plaintiff’s employment on 25th October, 2002.

And for such further or other orders as this court may deem fir to make in the circumstances.

At the close of pleadings and trial, the learned trial judge found in favour of the respondent. Appellant appealed against the decision. The appeal was determined based on appellant’s issues for determination, thus;

Whether considering the peculiar circumstances of this case, the terms of employment of the respondent thereto and the law, the termination of the respondent’s employment with the appellant was not in order.

Whether the dismissal of an employee summarily is distinguishable from termination of employment or both terms can be interpreted to mean one and the same thing and whether a misapprehension and application of the two terms by the lower court has occasioned a miscarriage of justice against the appellant.

Whether the award of ₦5,000,000.00 by the lower court as special and general damages in favour of the respondent was justified in law and on the evidence before the lower court when both damages were neither specifically pleaded and proved nor specially and separately prayed for as required by law.

The court finally decided amongst other things that “………………… the damages that the employee would be entitled to where the termination of employment is found to be wrongful, would be salaries for the length of time during which notice of termination would have been given in accordance with the contract of employment, in the instant case, the employee’s handbook, Exhibit ‘H’ or ‘J’. The plaintiff would also be paid legitimate entitlements due to him at the time the employment was brought to an end.

However, in the circumstances of this case, there was no evidence to warrant the finding that the termination of the employment of the Respondent was wrongful. The contract of employment guarantees the giving of Notice or salary in lieu of notice to terminate the contract. The Respondent would then be entitled to other legitimate entitlements due to him at the time the employment was brought to an end.” Per UWANI MUSA ABBA AJI, J.C.A (Pp. 36-37, PARAS. C-B)

It is clear from the foregoing that the quantum of damages applicable for wrongful termination is the amount which the employee would have lawfully earned if his employer had properly terminated the employment by giving the proper notice.

This also includes other benefits which the employee is lawfully entitled to under the contract of employment. But it does not include claims for sufferings, emotional damages and any other kind of sentimental damages.

Damages Applicable to Wrongful Dismissal (any similarities)?

As stated above, the difference between “dismissal” and “termination” is “Issuance of Notice” which is present in termination and mandatory but absent in dismissal and not required amongst other differences as stated above.

However, the damages applicable to dismissal is the same as damages applicable to termination and this can be seen in the plethora of cases such as IFETA v. SPDC NIG LTD (2006) LPELR-1436 (SC) where it was held that “In the case of The Nigerian Produce Marketing Board V. Adewunmi (1972) 11 SC 111 @ 117; (1972) NSCC 662 @ 665, this court (Per Fatayi Williams, JSC (as he then was) held- “In a claim for wrongful dismissal, the measure of damages is prima facie the amount that the plaintiff would have earned had the employment continued according to contract (see Beckham v. Drake (1849) 2 HLC 579 @ Pp. 607-608).

Where, however, the Defendant, on giving the prescribed notice, has a right to terminate the contract before the end of the term, the damages awarded, apart from other entitlements, should be limited to the amount which would have been earned by the plaintiff over the period of notice bearing in mind that it is the duty of the plaintiff to minimize the damages which he sustains by the wrongful dismissal……”

The facts of the afore-mentioned case are as follows;

The present Appeal emanated from the Delta State High Court, Warri, presided over by Narebor J., where plaintiff claimed as follows:

A declaration that the purported termination is wrongful, malicious, null and void and (of) no legal effect whatsoever.

The sum of ₦9,000,000.00 (Nine Million Naira) which represents the plaintiff’s salary from 1991-1996

The sum of ₦2,800,000.00 (Two Million, Eight Hundred Thousand Naira) which represents long service award entitlements

The sum of ₦200,000.00 (Two Hundred Thousand Naira) which represents long service award entitlement

The sum of ₦16,200,000.00 (Sixteen Million, Two Hundred Thousand Naira) which represents plaintiff’s salary till he retires. Or in the alternative to relief (e) above

An order for this Honourable Court reinstating the plaintiff to his rightful status which he would have presently occupied within the defendant company.

At the hearing of the case, only the appellant testified in support of his claims and no other witness was called by him. On the part of the Respondent, its learned counsel saw no need in calling evidence in the matter thereby leaving the statement of defence bare and unsupported. After receiving addresses from the learned counsel for the parties, the learned trial judge granted all the reliefs claimed by the appellant. Respondent appealed to the court of appeal. The appeal was successful. Appellant appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Appellant’s issues before the Supreme Court were;

Whether the learned Justices of the Court of Appeal Benin Division were right in holding that the appellant’s appointment was effectively brought to an end on 17-5-1991 notwithstanding failure of the respondent to give notice or payment of salaries in lieu of notice.

Whether in all the circumstances of this case, the proper measure of damages the appellant is entitled to is three months salaries in lieu of three months notice.

Whether failure of the Justices of the Court of Appeal Benin Division to adequately consider the legal consequence of oral termination in the circumstances of this case occasioned a miscarriage of justice.

The Respondents issues for determination were:

Was the court of appeal wrong in holding that the plaintiff’s employment was terminated on 17-5-1991?

Was the award of ₦7, 500.00 to the plaintiff as damages for wrongful termination of the contract of employment wrong?

In conclusion, the Supreme Court held the appeal to be lacking in merit and was accordingly dismissed.

ONI v. CADBURY NIG PLC (2012) LPELR-19815 (CA) in respect of the measure of damages recoverable for the wrongful dismissal of an employee, the court held that “Indeed, it is trite that damages recoverable in cases of wrongful dismissal or termination of an employee are the losses reasonably foreseeable by the parties at the material time of the contract as might inevitably arise from the breach thereof.

As authoritatively held by the Supreme Court, such recoverable damages do not include or take account of speculative or sentimental values. The court in awarding damages will certainly not include compensation for injured feelings or the fact that the employee having been dismissed makes it more difficult for him to obtain fresh employment. ………..” Per SAULAWA, J.C.A (Pp. 8-9, Paras E-C).

From the foregoing, it can safely be said that the quantum of damages recoverable for wrongful dismissal are;

The amount the Claimant would have earned had the employment continued according to contract or had it been lawfully determined.

The reasonably foreseeable losses by the parties at the time of contract which may inevitably arise from breach of contract.

The terms “dismissal” and “termination” do not bear the same meaning. They happen to mean on the surface the same thing but there are differences between these two. However, the Courts have more often than not used these terms interchangeably, thereby eroding their differences.

Irrespective of these differences which are not so obvious, the amount of damages applicable or recoverable for them is very similar. The foregoing is true from the various judicial authorities on them in respect of the quantum of damages recoverable for wrongful dismissal or termination.

Benita Ayo is an Associate/property consultant with Ayodele, Olugbenga & Co., 57, UBA HOUSE, 9th floor, Marina, Lagos. She may be contacted on: WhatsApp: 08063775768 and email: be*********@***oo.com.

Jobs/Appointments

Court Sanctions CHI Limited for Wrongful Employment Termination

By Modupe Gbadeyanka

The termination of the employment of one Mr Bodunrin Akinsuroju by CHI Limited has been declared as unlawful by the National Industrial Court of Nigeria.

Delivering judgment on the matter, Justice Sanda Yelwa of the Lagos Judicial Division of the court held that the sacking of Mr Akinsuroju did not comply strictly with the provisions of the contract of employment and the Employee Handbook.

Consequently, the company was directed to pay him the sum of N2 million as general damages for wrongful termination and N200,000 as costs of action, while Mr Akinsuroju was ordered to return the company’s properties in his possession or pay their assessed market value.

Justice Yelwa found that the contract agreement between both parties clearly required either party to give 30 days’ notice or payment in lieu of notice after confirmation of appointment, and there was no evidence that the employee was given the required notice or paid salary in lieu of notice.

The judge held that failure to comply with this fundamental term amounted to a breach of the contract of employment, thereby rendering the termination wrongful.

Mr Akinsuroju had claimed that the allegation of misconduct against him was unfounded and not established, maintaining that the disciplinary committee proceedings were prejudicial and that the termination of his employment was without justifiable cause and without compliance with the agreed terms of his employment.

In defence, CHI Limited contended that it had the right to terminate the employment of Mr Akinsuroju and that the termination was lawful and in accordance with the contract of employment and the Code of Conduct.

In opposition, counsel to Mr Akinsuroju submitted that the alleged breaches were not proved and that the termination letter took immediate effect without the requisite 30 days’ notice or payment in lieu of notice as stipulated in the letter of appointment and the Employee Handbook, urging the court to hold that the termination was wrongful and to grant the reliefs sought.

Jobs/Appointments

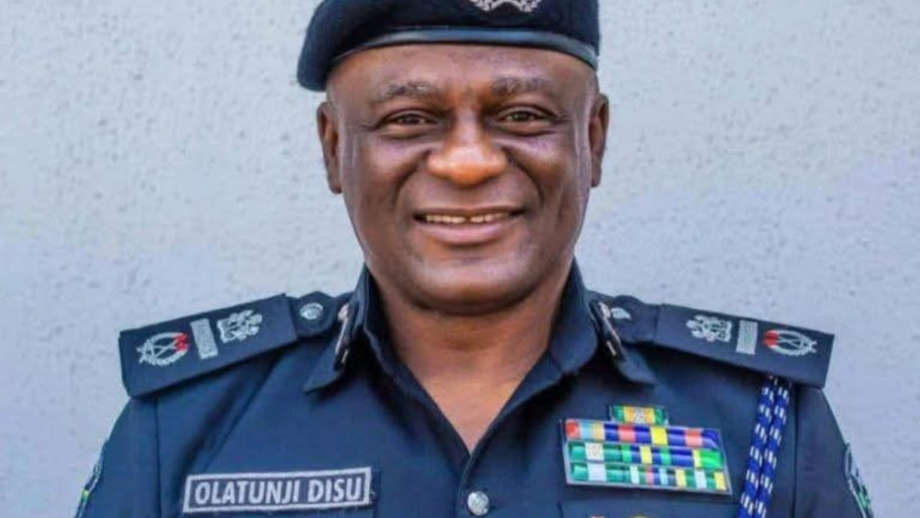

Tinubu Appoints Tunji Disu as Acting Inspector General of Police

By Modupe Gbadeyanka

President Bola Tinubu on Tuesday appointed Mr Tunji Disu as the acting Inspector General of Police (IGP), following the resignation of Mr Kayode Egbetokun.

Mr Disu, an Assistant Inspector General of Police (AIG), was recently moved to the Force Criminal Investigation Department (FCID) Annex, Alagbon, Lagos.

A statement today by the Special Adviser to the President on Information and Strategy, Mr Bayo Onanuga, disclosed that the President would convene a meeting of the Nigeria Police Council shortly to formally consider the appointment of Mr Disu as substantive IGP, after which his name will be transmitted to the Senate for confirmation.

Mr Tinubu expressed confidence that Mr Disu’s experience, operational depth, and demonstrated leadership capacity would provide steady and focused direction for the Nigeria Police Force during this critical period.

He reiterated his administration’s unwavering commitment to enhancing national security, strengthening institutional capacity, and ensuring that the Nigeria Police Force remains professional, accountable, and fully equipped to discharge its constitutional responsibilities.

Mr Egbetokun was said to have resigned from the position due to pressing family considerations.

President Tinubu, who accepted the resignation letter, expressed his profound appreciation for Mr Egbetokun’s decades of distinguished service to the Nigeria Police Force and the nation. He acknowledged his dedication, professionalism, and steadfast commitment to strengthening internal security architecture during his tenure.

Appointed in June 2023, Mr Egbetokun was serving a four-year term scheduled to conclude in June 2027, in line with the amended provisions of the Police Act.

The statement disclosed that his replacement was in view of the current security challenges confronting the nation, and acting in accordance with extant laws and legal guidance.

Jobs/Appointments

Tunji Disu to Become New IGP as Egbetokun Quits

By Adedapo Adesanya

Mr Tunji Disu, an Assistant Inspector General of Police (AIG), has reportedly replaced Mr Kayode Egbetokun as the new Inspector General of Police (IGP).

Mr Egbetokun resigned from the position on Tuesday after he was said to have held a meeting with President Bola Tinubu on Monday night at the Presidential Villa in Abuja.

President Tinubu appointed Mr Egebtokun as the 22nd IGP on June 19, 2023, with his appointment confirmed by the Nigeria Police Council on October 31, 2023.

Appointed as IGP at the age of 58, Mr Egbetokun was due for retirement on September 4, 2024, upon reaching the mandatory age of 60, but his tenure was extended by the President, creating controversies, which trailed him until his exit from the force today.

Although the police authorities are yet to comment on the matter or issue an official statement about his resignation, the move came amid reports suggesting that Mr Egbetokun has left the position.

Mr Egbetokun’s tenure was marred by a series of controversies; he recently initiated multiple charges against activist Mr Omoyele Sowore and his publication, SaharaReporters, after Mr Sowore publicly described him as an “illegal IGP.”

The dispute escalated into protracted legal battles, with the Federal High Court issuing injunctions restricting further publications relating to the former police chief and members of his family. Critics interpreted these court actions as attempts to stifle dissent and weaken press freedom.

His replacement, Mr Disu, was posted to oversee the Force Criminal Investigation Department (FCID) Annex, Alagbon, Lagos, some days ago.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn