World

Africa Needs to Eradicate Energy Poverty—NJ Ayuk

By Kester Kenn Klomegah

Understandably, energy is expected to drive Africa’s economic prosperity. In order to make great strides in the industrial sector and attain a high-level of sustainable development, for instance, energy is the key determining factor, argues NJ Ayuk, Executive Chairman of the African Energy Chamber, a pan-African company that focuses on research, documentation, negotiations and transactions in the energy sector.

According to him, scaling up Africa’s production capacity in order to achieve universal access to energy is a challenging task and points to the need for a transformative partnership-based strategy that aims to increase access to energy for all Africans.

He further talks about transparency, good governance and policies that could create a favourable investment climate, especially in the energy sector.

Speaking in an insightful interview with Kester Kenn Klomegah in early July 2021, NJ Ayuk unreservedly calls for strong foreign partnerships in harnessing and distribution of energy, stresses the significance of foreign investment in large-scale exploration projects in African countries.

Within the context of the newly created African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), he suggests that politicians, investors and stakeholders need to change the business perception and create an entirely new outlook into the future. Here are the interview excerpts:

What are the popular narratives about energy sources, production and utilization in Africa? In your expert view, how would you characterize energy needs in Africa?

The popular narratives are the prevalence of energy poverty on the continent. Most of the oil and gas producing countries have some kind of conflict going on in the area which affects the local people and the companies which choose to invest in these areas. For a country like Ghana, for example, we have seen the upside of the effective way of carrying out oil production, a major contribution has been its transparency and its policies.

African countries do, however, suffer from the policies they draft which take years to implement, and if implemented take long to administer the contracts for production to take effect. With that said, the effect on the upstream sector automatically affects the midstream and downstream, sectors, which essentially affects the economy of the different countries.

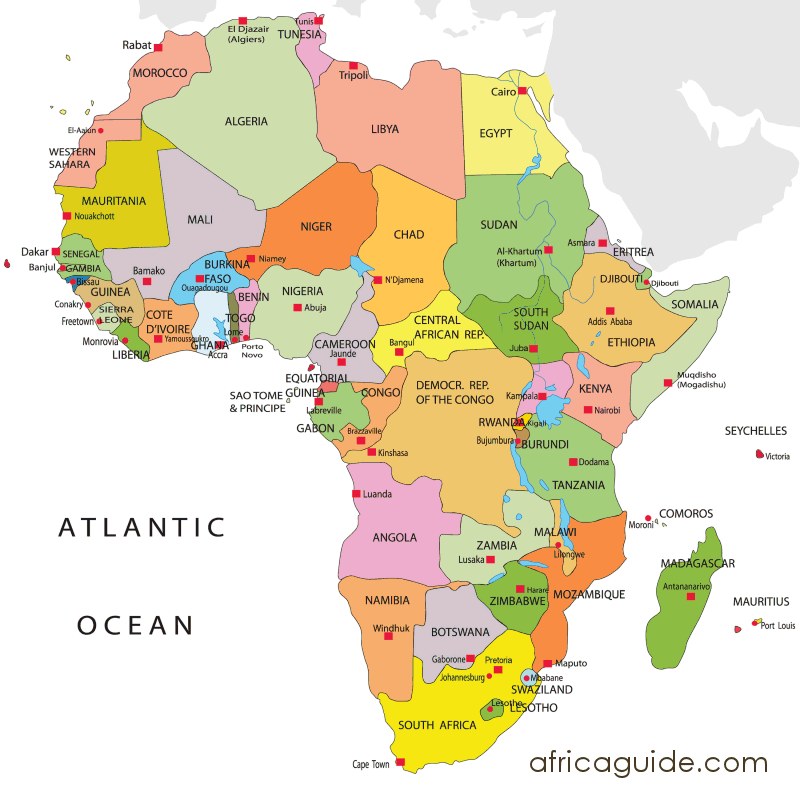

It’s without a doubt that energy poverty needs to be eradicated. Africa has the world’s lowest per capita energy consumption: with 16 per cent of the world’s population (1.18 billion out of 7.35 billion populations), it consumes about 3.3 per cent of global primary energy. Of all energy sources, Africa consumes the most oil (42 per cent of its total energy consumption) followed by gas (28 per cent), coal (22 per cent), hydro (6 per cent), renewable energy (1 per cent) and nuclear (1 per cent). South Africa is the world’s seventh-largest coal producer and accounts for 94 per cent of Africa’s coal production.

Africa’s renewable energy resources are diverse, unevenly distributed and enormous in quantity — almost unlimited solar potential (10 TW), abundant hydro (350 GW), wind (110 GW) and geothermal energy sources (15 GW). Energy from biomass accounts for more than 30 per cent of the energy consumed in Africa and more than 80 per cent in many sub-Saharan African countries. Sub-Saharan Africa has undiscovered, but technically recoverable, energy resources estimated at about 115.34 billion barrels of oil and 21.05 trillion cubic metres of gas.

Do African leaders see some of the controversial issues, in the same way, as you have discussed above?

In my opinion, African leaders do take heed of what has been discussed above but are too slow to tackle the issues, which eventually then build up. The effect of that is that once they have eventually tackled the first problem, they realize others have piled up and have to continue digging. Leaders also need to start bringing young people to the table who have fresher eyes and valuable contributions because of the times they live and are growing up in. A major contribution to that is the internet.

How do you assess the impact of energy deficit most especially within the context of the fourth industrial revolution? Is energy finance the determining factor here?

Firstly, we need good governance that creates an enabling environment for widespread economic growth and improved infrastructure. African leaders need an unwavering determination to make Africa work for us, even when there are missteps and things go wrong.

Without stability, projects and contracts cannot take effect. A recent example is an insurgency in Mozambique which has claimed lives but put a halt to a project which would have had a positive impact not only on Mozambique and its region but the entire continent. But now, we have to look ahead and not dwell on the shortcomings or pitfalls.

In order to change the tide and spur a post-pandemic recovery in the energy sector that will also enhance overall economic growth in Africa, African leaders must double their efforts to attract investment into their energy sectors. They must put in place timely and market-relevant strategies to deal with external headwinds like the drive to decarbonize globally and evolving demand patterns for energy internally and hydrocarbons globally. They must end restrictive fiscal regimes, inefficient and carbon-intensive production, cut bureaucracy and other difficulties in doing business that is preventing the industry from reaching its full potential.

What individual countries have set exceptional examples, at least, in offering energy and its utilization both in the urban cities and remote towns?

Consider the impact of energy deficiency. Approximately 840 million Africans, mostly in sub-Saharan countries, have no access to electricity. Hundreds of millions have unreliable or limited power at best.

Even during normal circumstances, energy poverty should not be the reality to most Africans. The household air pollution created by burning biomass, including wood and animal waste, to cook and heat homes has been blamed for as many as 4 million deaths per year. How will this play out during the pandemic? For women forced to leave their homes to obtain and prepare food, sheltering in place is nearly impossible. What about those who need to be hospitalized? Only 28 per cent of sub-Saharan Africa’s health care facilities have reliable power. Physicians and nurses can’t even count on the lights being on, let alone the ability to treat patients with equipment that requires electricity — or store blood, medications, or vaccines. All of this puts African lives are at risk.

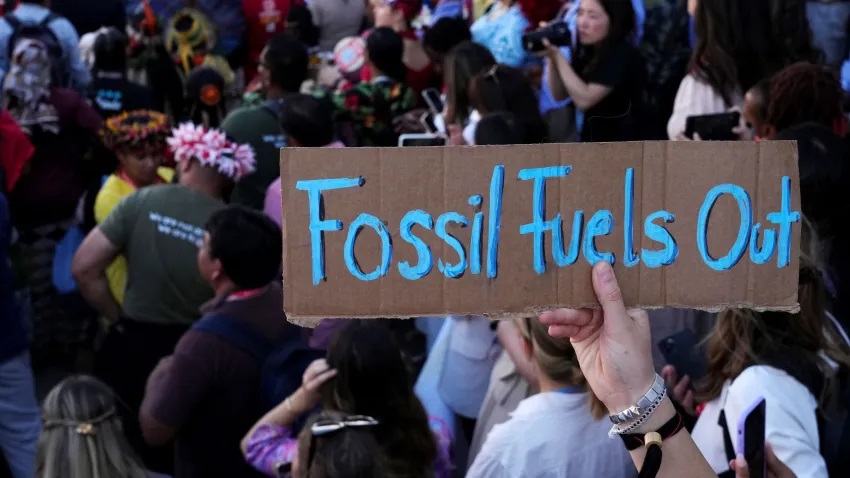

Africa does not need social programs, even educational programs, that come in the form of aid packages. What’s more, offering Africa aid packages to compensate for a halt or slow-down of oil and gas operations will not do Africans any good. This is not the time for Africa to be calling for more aid.

Africa has been receiving aid for nearly six decades, and what good has it done? We still don’t have enough jobs. Investment creates opportunities. We, as Africans, must be responsible. Our young people should be empowered to build an Africa we all can be proud of. Relying on the same old policies of the past, relying on aid, simply isn’t going to get us there.

Do you support expert views about “energy mix” — a combination of wind, solar, hydro and nuclear power? Why nuclear is still bug down with problems in Africa?

Straightway I would like to say yes. Africa must continue to bank on all forms of energy to address its shortfall in Energy production and distribution. From country to country, access to the generating resource will differ. Therefore, countries should focus on those resources to which they have easy and affordable access. Nuclear continues to be least accessible in Africa, due to the absence of technology and the high upfront construction costs associated with building such plants.

Africa has an almost unlimited renewable energy capacity, abundant access to solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal sources; however, except for a few large-scale projects, such potential is not adequately developed. What the continent needs is to reach a balance between reaching its energy transition goals and exploiting its natural resources, particularly natural gas, to ramp up power generation, generate jobs, and as a source of revenue. Natural gas’ potential to breathe new life into struggling African economies that are still reeling from the brutal economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Natural gas, affordable and abundant in Africa, has the power to spark significant job creation and capacity-building opportunities, economic diversification and growth. I am not saying that African nations should continue oil and gas operations indefinitely, with no movement toward renewable energy sources. I am saying that we should be setting the timetable for our own transition, and we should be deciding how it’s carried out. What I’d like to see, instead of Western pressure to bring African oil and gas activities to an abrupt halt, is a cooperative effort.

A number of foreign countries and private energy investing giants have shown interest in the energy sector. How do you assess the dynamics of their performance on the continent?

Local content is a pillar of the industry’s sustainability efforts. Sustainable development of African economies can only be attained by the development of local industry — by investing in Africans, building up African entrepreneurs and supporting the creation of indigenous companies. Oil companies have an unmatched ability, and a profound responsibility, to support countries in shaping an economy that works for all Senegalese and preserves their freedoms.

What is your view of Russia, considered as an energy giant, for instance, teaming up with China in Africa? Can both have a unified approach to collaborating on issues of energy projects in Africa?

First and foremost, Africa has already made an indelible mark in the oil and gas industry. I think Russian companies have to do more to really get involved. I always say that Africans want to get married, but Russians just want only to date. We need to change that and become more accountable. Both our compatriots expect better and more from our energy sectors.

As far as China and Russia are concerned, if both countries can avoid applying a “one size fits all” approach, so much good can come out of our oil and gas relationship with Russia. Africa has a lot to gain from Russian involvement and vice versa. Both must work towards empowering each other with concrete projects that bring benefit to investors and communities in which projects are situated. To be fair, positive developments from Russia and China don’t go unnoticed as their active presence in the continent leaves room for greater opportunities towards the energy mix.

World

AfBD, AU Renew Call for Visa-Free Travel to Boost African Economic Growth

By Adedapo Adesanya

The African Development Bank (AfDB) and the African Union have renewed their push for visa-free travel to accelerate Africa’s economic transformation.

The call was reinforced at a High-Level Symposium on Advancing a Visa-Free Africa for Economic Prosperity, where African policymakers, business leaders, and development institutions examined the need for visa-free travel across the continent.

The consensus described the free movement of people as essential to unlocking Africa’s economic transformation under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The symposium was co-convened by AfDB and the African Union Commission on the margins of the 39th African Union Summit of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa.

The participants framed mobility as the missing link in Africa’s integration agenda, arguing that while tariffs are falling under AfCFTA, restrictive visa regimes continue to limit trade in services, investment flows, tourism, and labour mobility.

On his part, Mr Alex Mubiru, Director General for Eastern Africa at the African Development Bank Group, said that visa-free travel, interoperable digital systems, and integrated markets are practical enablers of enterprise, innovation, and regional value chains to translate policy ambitions into economic activity.

“The evidence is clear. The economics support openness. The human story demands it,” he told participants, urging countries to move from incremental reforms to “transformative change.”

Ms Amma A. Twum-Amoah, Commissioner for Health, Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development at the African Union Commission, called for faster implementation of existing continental frameworks.

She described visa openness as a strategic lever for deepening regional markets and enhancing collective responses to economic and humanitarian crises.

Former AU Commission Chairperson, Ms Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, reiterated that free movement is central to the African Union’s long-term development blueprint, Agenda 2063.

“If we accept that we are Africans, then we must be able to move freely across our continent,” she said, urging member states to operationalise initiatives such as the African Passport and the Free Movement of Persons Protocol.

Ghana’s Trade and Industry Minister, Mrs Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare, shared her country’s experience as an early adopter of open visa policies for African travellers, citing increased business travel, tourism, and investor interest as early dividends of greater openness.

The symposium also reviewed findings from the latest Africa Visa Openness Index, which shows that more than half of intra-African travel still requires visas before departure – seen by participants as a significant drag on intra-continental commerce.

Mr Mesfin Bekele, Chief Executive Officer of Ethiopian Airlines, called for full implementation of the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM), saying aviation connectivity and visa liberalisation must advance together to enable seamless travel.

Regional representatives, including Mr Elias Magosi, Executive Secretary of the Southern Africa Development Community, emphasised the importance of building trust through border management and digital information-sharing systems.

Ms Gabby Otchere Darko, Executive Chairman of the Africa Prosperity Network, urged governments to support the “Make Africa Borderless Now” campaign, while tourism campaigner Ras Mubarak called for more ratifications of the AU Free Movement of Persons protocol.

Participants concluded that achieving a visa-free Africa will require aligning migration policies, digital identity systems, and border infrastructure, alongside sustained political commitment.

World

Nigeria Exploring Economic Potential in South America, Particularly Brazil

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this interview, Uche Uzoigwe, Secretary-General of NIDOA-Brazil, discusses the economic potential in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners for the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN). Follow the discussion here:

How would you assess the economic potential in the South American region, particularly Brazil, for the Federal Republic of Nigeria? What investment incentives does Nigeria have for potential corporate partners from Brazil?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, my response to the questions regarding the economic potentials in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners would be as follows:

Brazil, as the largest economy in South America, presents significant opportunities for the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The country’s diverse economy is characterised by key sectors such as agriculture, mining, energy, and technology. Here are some factors to consider:

- Natural Resources: Brazil is rich in natural resources like iron ore, soybeans, and biofuels, which can be beneficial to Nigeria in terms of trade and resource exchange.

- Growing Agricultural Sector: With a well-established agricultural sector, Brazil offers potential collaboration in agri-tech and food security initiatives, which align with Nigeria’s goals for agricultural development.

- Market Size: Brazil boasts a large consumer market with a growing middle class. This represents opportunities for Nigerian businesses looking to export goods and services to new markets.

- Investment in Infrastructure: Brazil has made significant investments in infrastructure, which could create opportunities for Nigerian firms in construction, engineering, and technology sectors.

- Cultural and Economic Ties: There are historical and cultural ties between Nigeria and Brazil, especially considering the African diaspora in Brazil. This can facilitate easier business partnerships and collaborations.

In terms of investment incentives for potential corporate partners from Brazil, Nigeria offers several attractive incentives for Brazilian corporate partners, including:

- Tax Incentives: Various tax holidays and concessions are available under the Nigerian government’s investment promotion laws, particularly in key sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and technology.

- Repatriation of Profits: Brazil-based companies investing in Nigeria can repatriate profits without restrictions, thus enhancing their financial viability.

- Access to the African Market: Investment in Nigeria allows Brazilian companies to access the broader African market, benefiting from Nigeria’s membership in regional trade agreements such as ECOWAS.

- Free Trade Zones: Nigeria has established free trade zones that offer companies the chance to operate with reduced tariffs and fewer regulatory burdens.

- Support for Innovation: The Nigerian government encourages innovation and technology transfer, making it attractive for Brazilian firms in the tech sector to collaborate, particularly in fintech and agriculture technology.

- Collaborative Ventures: Opportunities exist for joint ventures with local firms, leveraging local knowledge and networks to navigate the business landscape effectively.

In conclusion, fostering a collaborative relationship between Nigeria and Brazil can unlock numerous economic opportunities, leading to mutual growth and development in various sectors. We welcome potential Brazilian investors to explore these opportunities and contribute to our shared economic goals.

In terms of this economic cooperation and trade, what would you say are the current practical achievements, with supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, I would highlight the current practical achievements in economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil, alongside the supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA.

Here are some key points:

Current Practical Achievements

- Increased Bilateral Trade: There has been a notable increase in bilateral trade volume between Nigeria and Brazil, particularly in sectors such as agriculture, textiles, and technology. Recent trade agreements and discussions have facilitated smoother trade relations.

- Joint Ventures and Partnerships: Successful joint ventures have been established between Brazilian and Nigerian companies, particularly in agriculture (e.g., collaboration in soybean production and agricultural technology) and energy (renewables, oil, and gas), demonstrating commitment to mutual development.

- Investment in Infrastructure Development: Brazilian construction firms have been involved in key infrastructure projects in Nigeria, contributing to building roads, bridges, and facilities that enhance connectivity and economic activity.

- Cultural and Educational Exchange Programs: Programs facilitating educational exchange and cultural cooperation have led to strengthened ties. Brazilian universities have partnered with Nigerian institutions to promote knowledge transfer in various fields, including science, technology, and arts.

Supporting Strategies

- Strategic Trade Dialogue: NIDOA has initiated regular dialogues between trade ministries of both nations to discuss trade barriers, potential markets, and cooperative opportunities, ensuring both countries are aligned in their economic goals.

- Investment Promotion Initiatives: Targeted initiatives have been established to promote Brazil as an investment destination for Nigerian businesses and vice versa. This includes showcasing success stories at international trade fairs and business forums.

- Capacity Building and Technical Assistance: NIDOA has offered capacity-building programs focused on enhancing Nigeria’s capabilities in agriculture and technology, leveraging Brazil’s expertise and sustainable practices.

- Policy Advocacy: Continuous advocacy for favourable trade policies has been a key focus for NIDOA, working to reduce tariffs and promote economic reforms that facilitate investment and trade flows.

Systemic Engagement

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Engaging the private sector through PPPs has been essential in mobilising resources for development projects. NIDOA has actively facilitated partnerships that leverage both public and private investments.

- Trade Missions and Business Delegations: Organised trade missions to Brazil for Nigerian businesses and vice versa, allowing for direct engagement with potential partners, fostering trust and opening new channels for trade.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: NIDOA implements a rigorous monitoring and evaluation framework to assess the impact of various initiatives and make necessary adjustments to strategies, ensuring effectiveness in achieving economic cooperation goals.

Through these practical achievements, supporting strategies, and systemic engagement, NIDOA continues to play a pivotal role in enhancing economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil. By fostering collaboration and leveraging shared resources, we aim to create a sustainable and mutually beneficial economic environment that promotes growth for both nations.

Do you think the changing geopolitical situation poses a number of challenges to connecting businesses in the region with Nigeria, and how do you overcome them in the activities of NIDOA?

The changing geopolitical situation indeed poses several challenges for connecting businesses in the South American region, particularly Brazil, with Nigeria. These challenges include trade tensions, shifting alliances, currency fluctuations, and varying regulatory environments. Below, I will outline some of the specific challenges and how NIDOA works to overcome them:

Current Challenges

- No Direct Flights: This challenge is obviously explicit. Once direct flights between Brazil and Nigeria become active, and hopefully this year, a much better understanding and engagement will follow suit.

- Trade Restrictions and Tariffs: Increasing trade protectionism in various regions can lead to higher tariffs and trade barriers that hinder the movement of goods between Brazil and Nigeria.

- Currency Volatility: Fluctuations in the value of currencies can complicate trade agreements, pricing strategies, and overall financial planning for businesses operating in both Brazil and Nigeria.

- Different regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements in both countries can create challenges for businesses aiming to navigate these systems efficiently.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Changes in global supply chains due to geopolitical factors may disrupt established networks, impacting businesses relying on imports and exports between the two nations.

Overcoming Challenges through NIDOA.

NIDOA actively engages in discussions with both the Brazilian and Nigerian governments to advocate for favourable trade policies and agreements that reduce tariffs and improve trade conditions. This year in October, NIDOA BRAZIL holds its TRADE FAIR in São Paulo, Brazil.

What are the popular sentiments among the Nigerians in the South American diaspora? As the Secretary-General of the NIDOA, what are your suggestions relating to assimilation and integration, and of course, future perspectives for the Nigerian diaspora?

As the Secretary-General of NIDOA, I recognise the importance of understanding the sentiments among Nigerians in the South American diaspora, particularly in Brazil.

Many Nigerians in the diaspora take pride in their cultural roots, celebrating their heritage through festivals, music, dance, and culinary traditions. This cultural expression fosters a sense of community and belonging.

While many individuals embrace their new environments, they often face challenges related to cultural differences, language barriers, and social integration, which can lead to feelings of isolation.

Many express optimism about opportunities in education, business, and cultural exchange, viewing their presence in South America as a chance to expand their horizons and contribute to economic activities both locally and back in Nigeria.

Sentiments regarding acceptance vary; while some Nigerians experience warmth and hospitality, others encounter prejudice or discrimination, which can impact their overall experience in the host country. NIDOA BRAZIL has encouraged the formation of community organisations that promote networking, cultural exchange, and social events to foster a sense of belonging and support among Nigerians in the diaspora. There are currently two forums with over a thousand Nigerian members.

Cultural Education and Awareness Programs: NIDOA BRAZIL organises cultural education programs that showcase Nigerian heritage to local communities, promoting mutual understanding and appreciation that can facilitate smoother integration.

Language and Skills Training: NIDOA BRAZIL provides language courses and skills training programs to help Nigerians, especially students in tertiary institutions, adapt to their new environment, enhancing communication and employability within the host country.

Engaging in Entrepreneurship: NIDOA BRAZIL supports the entrepreneurial spirit among Nigerians in the diaspora by facilitating access to resources, mentorship, and networks that can help them start businesses and create economic opportunities.

Through its AMBASSADOR’S CUP COMPETITION, NIDOA Brazil has engaged students of tertiary institutions in Brazil to promote business projects and initiatives that can be implemented in Nigeria.

NIDOA BRAZIL also pushes for increased tourism to Brazil since Brazil is set to become a global tourism leader in 2026, with a projected 10 million international visitors, driven by a post-pandemic rebound, enhanced air connectivity, and targeted marketing strategies.

Brazil’s tourism sector is poised for a remarkable milestone in 2026, as the country expects to welcome over 10 million international visitors—surpassing the previous record of 9.3 million in 2025. This expected surge represents an ambitious leap, nearly doubling the country’s foreign-arrival numbers within just four years, a feat driven by a combination of pent-up global demand, strategic air connectivity improvements, and a highly targeted marketing campaign.

World

African Visual Art is Distinguished by Colour Expression, Dynamic Form—Kalalb

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this insightful interview, Natali Kalalb, founder of NAtali KAlalb Art Gallery, discusses her practical experiences of handling Africa’s contemporary arts, her professional journey into the creative industry and entrepreneurship, and also strategies of building cultural partnership as a foundation for Russian-African bilateral relations. Here are the interview excerpts:

Given your experience working with Africa, particularly in promoting contemporary art, how would you assess its impact on Russian-African relations?

Interestingly, my professional journey in Africa began with the work “Afroprima.” It depicted a dark-skinned ballerina, combining African dance and the Russian academic ballet tradition. This painting became a symbol of cultural synthesis—not opposition, but dialogue.

Contemporary African art is rapidly strengthening its place in the world. By 2017, the market was growing so rapidly that Sotheby launched its first separate African auction, bringing together 100 lots from 60 artists from 14 foreign countries, including Algeria, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, and others. That same year during the Autumn season, Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris hosted a major exhibition dedicated to African art. According to Artnet, sales of contemporary African artists reached $40 million by 2021, a 434% increase in just two years. Today, Sotheby holds African auctions twice a year, and in October 2023, they raised $2.8 million.

In Russia, this process manifests itself through cultural dialogue: exhibitions, studios, and educational initiatives create a space of trust and mutual respect, shaping the understanding of contemporary African art at the local level.

Do you think geopolitical changes are affecting your professional work? What prompted you to create an African art studio?

The international context certainly influences cultural processes. However, my decision to work with African themes was not situational. I was drawn to the expressiveness of African visual language—colour, rhythm, and plastic energy. This theme is practically not represented systematically and professionally in the Russian art scene.

The creation of the studio was a step toward establishing a sustainable platform for cultural exchange and artistic dialogue, where the works of African artists are perceived as a full-fledged part of the global cultural process, rather than an exotic one.

To what extent does African art influence Russian perceptions?

Contemporary African art is gradually changing the perception of the continent. While previously viewed superficially or stereotypically, today viewers are confronted with the depth of artistic expression and the intellectual and aesthetic level of contemporary artists.

Portraits are particularly impactful: they allow us to see not just an abstract image of a “continent,” but a concrete personality, character, and inner dignity. Global market growth data and regular auctions create additional trust in African contemporary art and contribute to its perception as a mature and valuable movement.

Does African art reflect lifestyle and fashion? How does it differ from Russian art?

African art, in my opinion, is at its peak in everyday culture—textiles, ornamentation, bodily movement, rhythm. It interacts organically with fashion, music, interior design, and the urban environment. The Russian artistic tradition is historically more academic and philosophical. African visual art is distinguished by greater colour expression and dynamic form. Nevertheless, both cultures are united by a profound symbolic and spiritual component.

What feedback do you receive on social media?

Audience reactions are generally constructive and engaging. Viewers ask questions about cultural codes, symbolism, and the choice of subjects. The digital environment allows for a diversity of opinions, but a conscious interest and a willingness to engage in cultural dialogue are emerging.

What are the key challenges and achievements of recent years?

Key challenges:

- Limited expert base on African contemporary art in Russia;

- Need for systematic educational outreach;

- Overcoming the perception of African art as exclusively decorative or ethnic.

Key achievements:

- Building a sustainable audience;

- Implementing exhibition and studio projects;

- Strengthening professional cultural interaction and trust in African

contemporary art as a serious artistic movement.

What are your future prospects in the context of cultural diplomacy?

Looking forward, I see the development of joint exhibitions, educational programs, and creative residencies. Cultural diplomacy is a long-term process based on respect and professionalism. If an artistic image is capable of uniting different cultural traditions in a single visual space, it becomes a tool for mutual understanding.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn