Economy

How I Went Bankrupt Because of Abacha’s Death—Tonye Cole

Nigeria is a nation that knows all too well what damage dictatorships can do. Between 1966 and 1999, the country saw several military coups, culminating in Sani Abacha seizing power. From 1993 to 1998, Abacha’s rule marked a period of oppression, inflation and poverty. As a business owner, the main objective was to stay afloat.

For those brave enough to speak out against the regime, the punishment was either death by hanging or prison. Atrocities were commonplace in an atmosphere of desolation. In 1998, when Abacha died, Tonye Cole, the Co-Founder of Sahara Group, remembers it like yesterday.

“I remember exactly where I was when Abacha died. I remember people jubilating and singing and it was as if an air of relief had happened. I remember my partner had just got married and we were closing a major transaction so he delayed his honeymoon and stayed in Lagos. It is one of those moments in life where you remember key places you were. And the first expression was that of relief from everybody and then the next day reality set in,” says Cole.

“I remember exactly where I was when Abacha died. I remember people jubilating and singing and it was as if an air of relief had happened. I remember my partner had just got married and we were closing a major transaction so he delayed his honeymoon and stayed in Lagos. It is one of those moments in life where you remember key places you were. And the first expression was that of relief from everybody and then the next day reality set in,” says Cole.

Tonye Cole for the first time in years, hope dispelled despair. Cole was invested and happy.

“My partners and I had been working for three years and pushing ourselves really hard. We just got to the point where we were establishing ourselves as a business. Everything seemed to be going right. We had been working on an oil transaction and collected our allocation to load the products. At that point, all the brokers who we collected our oil allocation from had been paid by us. This is what you call betting on the horse. We had taken everything we owned and put it on this single deal,” says Cole.

Cole believed there was nothing more to be done but wait for the return on investment. Then the new government cancelled every contract that was issued by the Abacha administration.

The three young men had pumped everything they had earned for the past two years into the deal. Overnight, Cole and his partners went bankrupt. The trio had invested $400,000 of their savings in the supply and distribution of oil contracts from their new venture. For Cole, this was not the first time he lost everything. The first time was the catalyst for him to take control of his own fate. Ironically, he was hitting rock bottom again.

“If you are an entrepreneur, you are going to get bad days and if you are a successful one you are going to get even more bad days. As young people, this was all we had. People had collected their commission and nobody wanted to help us. We knew we had nothing to lose. Everything was gone. The good thing was that we had records and payment to brokers and their assignments they had given us. So we put the files together and walked into the office of a man we had never met before. We waited until we had an opportunity to speak to him and we locked the door,” says Cole.

It was 2PM on a Monday. The drive to the office of Mallam Lawan Buba, Group Executive Director, Commercial and Investment, Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC), was a quiet one with all three men contemplating the gravity of what had just happened. Cole remembered advice his father, Patrick, had given him years ago. He told his son to spend five years working and learning from different companies before embarking on his own business venture. Cole had already served the five years but, in hindsight, he wondered if an additional five years could have saved him from this catastrophe.

Cole and his partners spent weeks trying to secure an appointment with the man seated in front of them that day. As Cole stood in Buba’s office, a fleeting fear gripped him. They had leveraged their one good relationship with the company’s secretary to get this appointment and if things did not go according to plan, not only would they still be bankrupt but the secretary could lose her job as well. Cole tried to read the expression on the face of Buba and drew a blank. He then regained his composure and approached the man who had the power to change their destiny.

The trio made their impassioned plea to Buba, the man responsible for the allocation of oil contracts. They showed him their legitimate contracts, payments made and financial records for the past three years. Cole took a cue from his father’s days running for president of Nigeria and gave a fervent speech on why they believed they could make a difference by creating employment and establishing an indigenous oil business, one of the first of its kind.

Buba listened to their plea and told them to wait. That was the end of the journey; there was nothing more the young entrepreneurs could do. As they left, it occurred to Cole that this could be the end of a lifetime of hard work.

“Failure teaches you a lot. As an entrepreneur I am not afraid of failure but I must learn from it,” says Cole.

During the two-hour trip back home, Cole’s life flashed before him.

Cole had three major influences growing up. His creative side was nourished by his mother, who was a journalist for one of the leading publications in Nigeria. From his father, Cole learned the skills of diplomacy and how to be a mediator on account of his role as an ambassador to Brazil. From his stepmother, Cole was given the foundations of the Christian faith upon which he built his life principles. Born in January 1967 in Port Harcourt, the capital of Rivers State, Cole and his family relocated to Anambra State during the civil war. Cole had a nomadic existence, shuffling between guardians. He learned to be self-sufficient and stumbled into his career by what he calls divine intervention.

“I ended up studying architecture because the subjects I had taken for O-levels in secondary school aligned more with the profession. I went to the University of Lagos to study architecture and then found that it was something that was perfectly suited for me. It rewards extreme hard work and punishes laziness to a fault. You had to imagine things and create it in your mind long before it comes on paper,” says Cole.

After university, Cole joined Brazilian architectural firm Grupo Quattro SA where he oversaw the construction of the new Palmas city developments in Tocantins, Brazil. This was a slight deviation from his plan to work for himself.

“When I was in university, we had already set up a business where I created architectural drawings and designs for different companies and teachers, as well as perfecting their existing designs,” he says.

Cole’s father influenced his decision to go to Brazil and leave.

“I have this belief and patriotic zeal in Nigeria and I believe we all have a role to play. My father had decided to run for the presidency in Nigeria and I decided to relocate to help him with his campaign,” he says.

Back in Nigeria, Cole Joined EMSA S.A. – one of Brazil’s largest engineering firms. He was the head of operations and business development in the country.

“They needed someone in Nigeria who could speak Portuguese and someone they could trust to implement a World Bank project. I now had this job, which was an engineering job, and it involved traveling around the country meeting government officials and business development. I had a wonderful salary at an expatriate rate, a company car and all the corporate perks. I had no interest at this point to do anything entrepreneurial. I was very comfortable,” says Cole.

Nigeria had just fallen under Abacha’s military regime. The initial hope and excitement turned to gloom. Almost overnight, the military started throwing people in jail. Riots ensued all over the country, leading to the exit of foreign businesses, like EMSA, from the Nigerian economy. The company signed off all the contracts and instructed Cole to liquidate everything.

“I said to myself ‘I am never leaving my fate in another person’s hands again,’” says Cole.

Prior to this, Tope Shonubi and Ade Odunsi had teamed up to start a new business venture in the burgeoning oil industry. Cole had turned down the offer to join the team in favour of his hefty salary and company perks. The offer was made once again, and now finding himself unemployed, Cole accepted. It was the birth of the Sahara Group, a leading private power, energy, gas and infrastructure conglomerate established two years before the end of Abacha’s rule in 1998.

All of this led to Cole walking out of the office of Buba, the man with their oil contracts. A week later, they got a call promising to reinstate their cancelled contracts over one year. Cole learned a valuable lesson.

“Don’t rely on one product and one country. In 1998, we got some of our contracts back and by 1999 we were in Ghana and then subsequently in Côte d’Ivoire, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Singapore and the UAE.”

Today, the Group has around 20 operations across the energy sector with 660 employees. Sahara began as a facilitator in the oil sector, acting as a middleman between producers, marketers and traders. This year marks their 20-year anniversary and there is a lot to celebrate. The company has diversified into utilities, real estate, farming and infrastructure. Among its many developments is the $400-million Lekki power project in Lagos.

“When we came in there were not a lot of people in the business of trading and exploration of oil. When you talk about someone in the oil business back then, the most they would be were petrol station owners. We were the first pioneers to come into this aspect of the business,” says Cole.

Being trailblazers served the company well. The first major break happened about a year and a half after the company started. A major tool in the oil trade is the ability to have a letter of credit, popularly known as an LC. This is a guarantee taken on by a bank to make payments on behalf of the client, provided certain terms are met.

As brokers, Cole and his team will get allocations and trade them off to those who had an LC and then get their commission from the deal and plough it back into the business. For the initial period, Sahara could not open an LC, which was a major stumbling block for its growth.

“We couldn’t even open a dollar account in the beginning because the banks did not trust Nigerian businesses and this is a dollar denominated business. So we had to use a lot of innovation to get LCs. We asked our international clients to open an account for us so we could receive the payments, which they did with ease and secondly, we made sure that any LCs our clients opened, was done in our name,” says Cole.

Another major breakthrough happened when financial giant BNP Paribas approached the firm after two years of trading and helped them to finally open an LC in the company’s name.

As Cole turns 49 this year, he is slightly nostalgic when asked about his success in the oil business. He takes a deep breath and, for the first time during his interview, the charismatic and energetic entrepreneur assumes an almost vulnerable disposition as he talks of his multimillion-dollar empire.

“I am not sure I will be anywhere I am without my wife. She has allowed me to work and to be able to do what I do. I travel a lot and the ability to come in and go out without anybody being as clingy and commanding has been very helpful. Family wise, she makes me look good with everybody in my family because she is the one who keeps in touch with everyone. She is my perfect complement,” he says.

Cole met the love of his life 22 years ago at university. She was 16 going on 17 and he was in his third year of studies at the age of 18. Cole spent two years trying to convince his wife that he was the perfect match for her and years later, with three children, he calls her the glue that holds everything together.

Success can be fleeting. It has been a number of years since the company almost went bankrupt. In those days, the focus was on staying afloat as a business. Today, the Sahara Group has set up a foundation with a mandate of helping 12 million people in the next four years. The company contributes 5% of its profit to the foundation, which has worked with international not-for-profit organizations to eradicate Guinea worm disease, cataracts and cleft palates.

Faced with a global drop in oil prices, a resurgence of Boko Haram in the north of Nigeria and conflict in the Niger Delta, the West African nation’s economy is facing economic and social challenges. For Cole, his fate is firmly back in his hands. He has a much better understanding of the industry he operates in.

“We are in a boom and bust business, so these challenges are all part of life. We know when it is high and when it is low. Once oil prices are low you adjust immediately as an organization. You look at waste and how to cut it. We try as much as possible not to cut staff, we talk to them and let them understand that they need to be a lot more efficient in the things they do. It is all about planning ahead,” he says.

As Cole looks to the future, he sums up the strategy that has served him well so far.

“Let people think you have 10, act like you have only one but make sure you have 100.”

Economy

Flour Mills Supports 2026 Paris International Agricultural Show

By Modupe Gbadeyanka

For the second time, Flour Mills of Nigeria Plc is sponsoring the Paris International Agricultural Show (PIAS) as part of its strategies to fortify its ties with France.

The 2026 PIAS kicked off on February 21 and will end on March 1, with about 607,503 visitors, nearly 4,000 animals, and over 1,000 exhibitors in attendance last year, and this year’s programme has already shown signs of being bigger and better.

The theme for this year’s event is Generations Solution. It is to foster knowledge transfer from younger generations and structure processes through which knowledge can be harnessed to drive technological advancement within the global agricultural sector.

In his address on the inaugural day of the Nigerian Pavilion on February 23, the Managing Director for FMN Agro and Director of Strategic Engagement/Stakeholder Relations, Mr Sadiq Usman, said, “At FMN, our mission is Feeding and Enriching Lives Every Day.

“This is a mandate we have fulfilled through decades of economic shifts, rooted in a culture of deep resilience and constant innovation. We support this pavilion because FMN recognises that the next frontier of global Agribusiness lies in high-level technical exchange.

“We thank the France-Nigeria Business Council (FNBC), the organisers of the PIAS, and our fellow members of the Nigerian Pavilion – Dangote, BUA, Zenith, Access, and our partners at Creativo El Matador and Soilless Farm Lab— we are exceedingly pleased to work to showcase the true face of Nigerian commerce.”

Speaking on the invaluable nature of the relationship between Nigeria and France, and the FMN’s commitment to process and product innovation, Mr John G. Coumantaros, stated, “The France – Nigeria relationship is a valuable partnership built on a shared value agenda that fosters remarkable Intercontinental trade growth.

“Also, as an organisation with over six decades of transformational footprint in Nigeria and progressively across the African Continent, FMN has been unwaveringly committed to product and process innovation.

“Therefore, our continuous partnership with France for the success of the Paris International Agricultural Show further buttresses the thriving relationship between both countries.”

PIAS is one of the most widely attended agricultural shows, with thousands of people from across the world in attendance.

Economy

NEITI Backs Tinubu’s Executive Order 9 on Oil Revenue Remittances

By Adedapo Adesanya

Despite reservations from some quarters, the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) has praised President Bola Tinubu’s Executive Order 9, which mandates direct remittances of all government revenues from tax oil, profit oil, profit gas, and royalty oil under Production Sharing Contracts, profit sharing, and risk service contracts straight to the Federation Account.

Issued on February 13, 2026, the order aims to safeguard oil and gas revenues, curb wasteful spending, and eliminate leakages by requiring operators to pay all entitlements directly into the federation account.

NEITI executive secretary, Musa Sarkin Adar, called it “a bold step in ongoing fiscal reforms to improve financial transparency, strengthen accountability, and mobilise resources for citizens’ development,” noting that the directive aligns with Section 162 of Nigeria’s Constitution.

He noted that for 20 years, NEITI has pushed for all government revenues to flow into the Federation Account transparently, calling the move a win.

For instance, in its 2017 report titled Unremitted Funds, Economic Recovery and Oil Sector Reform, NEITI revealed that over $20 billion in due remittances had not reached the government, fueling fiscal woes and prompting high-level reforms.

Mr Adar described the order as a key milestone in Nigeria’s EITI implementation and urged amendments to align it with these reforms.

He affirmed NEITI’s role in the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) and pledged close collaboration with stakeholders, anti-corruption bodies, and partners to sustain transparent management of Nigeria’s mineral resources.

Meanwhile, others like the Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN) have kicked against the order, saying it poses a serious threat to the stability of the oil and gas industry, calling it a “direct attack” on the PIA.

Speaking at the union’s National Executive Council (NEC) meeting in Abuja on Tuesday, PENGASSAN President, Mr Festus Osifo, said provisions of the order, particularly the directive to remit 30 per cent of profit oil from Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs) directly to the Federation Account, could destabilise operations at the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) Limited.

Mr Osifo firmly dispelled rumours of imminent protests by the union, despite widespread claims that the controversial executive order threatens the livelihoods of 10,000 senior staff workers at NNPC.

He noted, however, that the union had begun engagements with government officials, including the Presidential Implementation Committee, and expressed optimism that common ground would be reached.

Mr Osifo, who also serves as President of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), expressed concerns that diverting the 30 per cent profit oil allocation to the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC), without clearly defining how the statutory management fee would be refunded to NNPC, could affect the salaries of hundreds of PENGASSAN members.

Economy

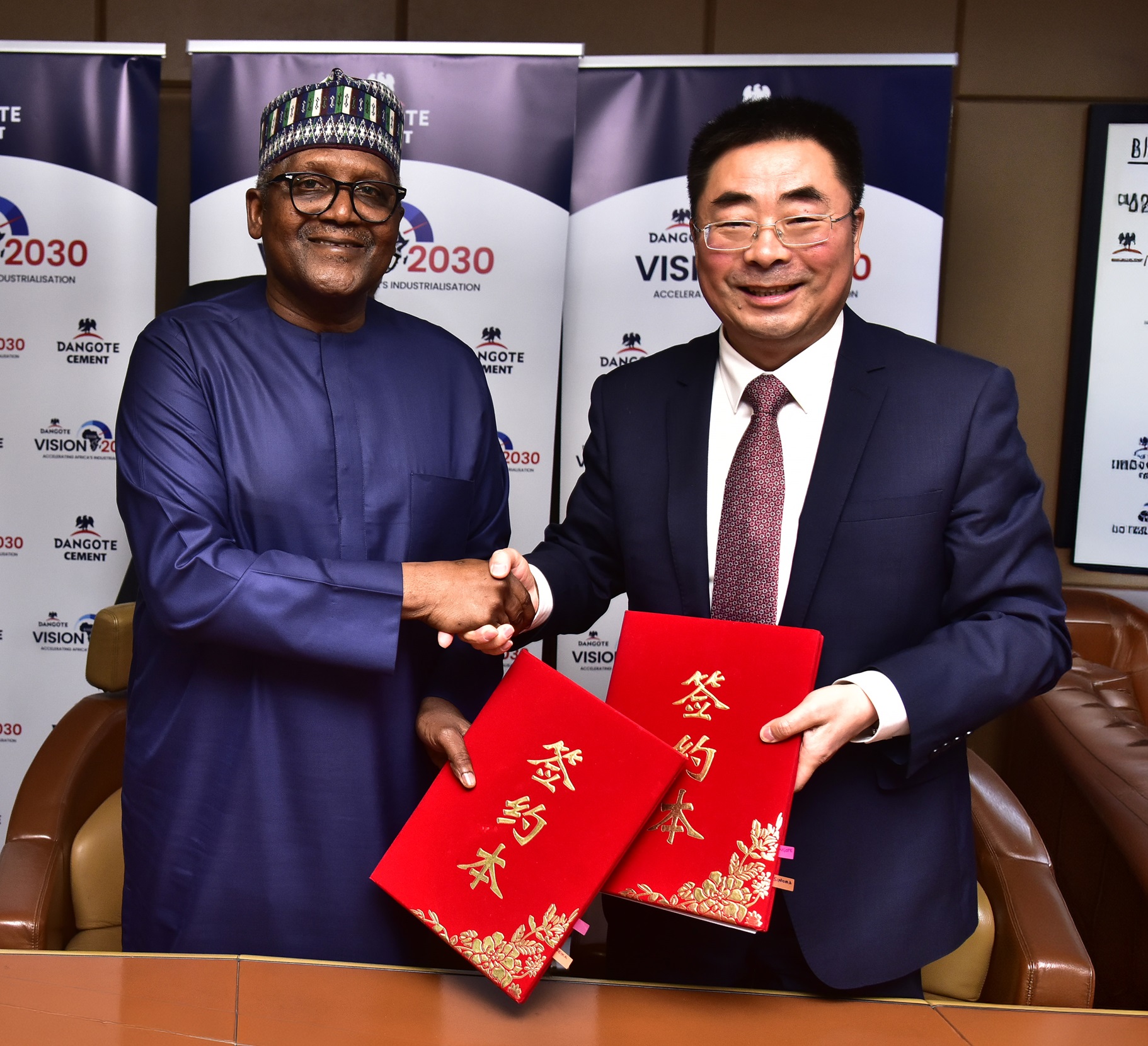

Dangote Cement Deepens Dominance, Export Activities With $1bn Sinoma Deal

By Aduragbemi Omiyale

To strengthen its domestic market dominance, drive its export activities, optimise existing operational assets and enhance production efficiency and capacity expansion, Dangote Cement Plc has sealed $1 billion strategic agreements with Sinoma International Engineering for cement projects across Africa.

The president of Dangote Industries Limited, the parent firm of Dangote Cement, Mr Aliko Dangote, disclosed that the deal reinforces the company’s long-term growth strategy and aligns with the broader aspirations of the Dangote Group’s Vision 2030.

According to him, Sinoma will construct 12 new projects and expand others for the cement organisation across Africa, helping to achieve 80 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) production capacity by 2030, while supporting the group’s overarching target of generating $100 billion in revenue within the same period.

Under the Strategic Framework Agreement, Sinoma will collaborate with Dangote Cement on the delivery of new plants, brownfield expansions, and modernisation initiatives aimed at strengthening operational performance across key markets.

The new projects include a new integrated line in Northern Nigeria with a satellite grinding unit, a new line in Ethiopia and other projects in Zambia/Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Sierra Leone and Cameroon. In Nigeria, Sinoma will also handle different projects in Itori, Apapa, Lekki, Port Harcourt and Onne.

The projects signal Dangote Cement’s sustained commitment to consolidating its leadership position within the African cement industry, while enhancing its competitiveness on the global stage.

Chairman of the Dangote Cement board, Mr Emmanuel Ikazoboh, during the agreement signing event in Lagos, explained that the new projects would enable the company to play a critical role in actualising Dangote Group’s Vision 2030.

The new projects, when completed, will increase Dangote Cement’s capacity and dominant position in Africa’s cement industry.

On his part, the Managing Director of Dangote Cement, Mr Arvind Pathak, said the agreement reflects the company’s determination to grow its investments across African markets to close supply gaps and support the continent’s infrastructural ambitions.

According to him, Dangote Cement is committed to making Africa fully self‑sufficient in cement production, creating more value and linkages, leading to increased economic activities and a reduction in unemployment.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn