Economy

Riskmap 2017: A Year of Acute Uncertainty for Business

By Modupe Gbadeyanka

Control Risks, the specialist risk consultancy, has published its annual RiskMap forecast, the leading guide to political and business risk and an important reference for policy makers and business leaders.

Richard Fenning, CEO, Control Risks, said: “The unexpected US election and Brexit referendum results that caught the world by surprise have tipped the balance to make 2017 one of the most difficult years for business’ strategic decision making since the end of the Cold War.

The catalysts to international business – geopolitical stability, trade and investment liberalisation and democratisation – are facing erosion. The commercial landscape among government, private sector and non-state actors is getting more complex.”

By the end of 2017 we will know whether or not the global economy withstood the shocks and turbulence of 2016, if the US opted for a new definition of how to exercise its power and if the great experiment in globalisation remains on track.”

The high levels of complexity and uncertainty attached to the key political and security issues for the year, highlighted by RiskMap, mean that boards will need to undertake comprehensive reviews of their approaches to risk management.

Control Risks has identified the following key business risks for 2017:

Increased policy and political uncertainty as a result of heightened olitical populism pexemplified by President-elect Trump and Brexit. The era of greater national control of economic and security policy ushered in by the US election and Brexit provides increased uncertainty for business leaders. Caution prevails because of the lack of political policy clarity from the USA and UK and the impacts on the global trading and economic environment, as well as geopolitics. Political sparks will fly as the new presidency places pressure on the economic relationship between the US and China, vital for the stability of the global economy; and the US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership threatens to redraw trans-Pacific commerce. The calls across Europe for further referendums on EU membership is causing nervousness and populism in other parts of the world such as sub-Saharan Africa is adding fuel to investor risk.

Persistent terrorist threats driven by the weakening of the Islamic State. The threat of terrorism will remain high in 2017 but become more fragmented. The eventual collapse of Islamic State’s territorial control in Syria and Iraq will lead to an exodus of experienced militants across the world. Responding to terrorism is becoming ever more difficult for businesses; risk adjustment is critical, including big data solutions and reviews of potential insider radicalisation, physical security and scenario planning.

Increasing complexity of cyber security and associated attempts by governments to regulate data transfers. 2017 will see the rise of conflicting data legislation: US and EU data protection regulations remain at odds; the EU’s Single Digital Market is isolationist; and China and Russia are introducing new cyber security laws. This will lead to data nationalism, forcing companies to store data locally, at increased cost, as they are unable to meet regulatory requirements in international data transfer. E-commerce will be stifled. Fears of terrorism and state sponsored cyber-attacks will exacerbate national legislation, adding burden to businesses.

Intensifying geopolitical pressures driven by nationalism, global power vacuums and proxy conflicts. Syria, Libya, Yemen and Ukraine are likely to remain intractable conflicts and the Middle East will continue to be shaped by friction between Saudi Arabia and Iran; China’s increased focus on diplomacy and military influence will extend from Central Asia and the Indian Ocean to sub-Saharan Africa; and North Korea’s systematic nuclear capability development is upending a relatively static regional and global nuclear status quo.

The militarisation of strategic confrontations by accident or miscalculation. While major conflicts remain unlikely in the South or East China Seas, for example, further militarisation of disputes among China, its neighbours and the US, is likely; Saudi Arabia and Iran continue to jockey for position in the Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb straits; Iran’s nuclear deal has emboldened the country to challenge the US-Saudi security infrastructure; and Russia is likely to maintain substantial air patrols in or near European airspace and will continue bolstering its Black Sea and Mediterranean naval fleets to secure its positions in Crimea and Syria.

Richard Fenning continued: “Digitalisation and the internet of everything takes risk everywhere and the distinction between safe home markets and dangerous foreign ones has largely gone. The sheer mass of stored data, teetering on a fulcrum between asset and liability, has shifted the gravitational centre of risk.

Terrorist attacks across continents in 2016 made possible in large part by the internet have shown that Islamist inspired violence can be planned and carried out anywhere in the world.”

With the seismic shift in risk scenario planning now required by businesses, we can expect the competitive playing field in many industries to see significant change as organisations respond in different ways to the multitude of complexities facing them.”

Companies will pursue different strategies to protect value and seize opportunity in 2017. Many organisations will be defined as Arks, Sharks or Whales by their response.

Arks will be defensive and focus on core businesses and markets. They will shed non-performing assets, reverse unsuccessful mergers, cut costs, and delay expansion. While particularly associated with mining and oil and gas due to the collapse in commodity prices, the Ark strategy also characterises retrenchment by retailers and re-shoring by manufacturers.

Sharks are less risk-averse and will hunt for opportunities in new activities and locations. Financial services, facing regulatory uncertainty and the rise of competing power centres in the emerging world, is likely to take on risk to capture first-mover advantages in frontier markets or disruptive sectors such as fintech.

Whales will take advantage of their deep pockets and cheap financing to engineer mega-mergers and monopolise markets. Their main risks are economic nationalists and competition regulators. Consolidation strongly characterises the technology sector, pharmaceuticals, and agribusiness, which have often arbitraged regulatory environments to gain dominant market positions.

Executive summary by select regions:

The EU after Brexit. Brexit will not be transformative for the remaining 27 EU countries. The UK’s departure from the union will encourage some member states to be more assertive but it will not lead to mass popular uprisings against the EU’s institutions. If the British decision to leave the EU makes the bloc stronger, it will be via marginal gains, rather than the dawning of a bold new era.

Middle East: The politics and pitfalls of privatisation. A privatisation push across the Middle East and North Africa in 2017, including in Algeria, Egypt, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, will act as a siren call to investors around the world. As foreign companies prepare bids for new projects and tune into public debates about the benefits that privatisation offers, they should closely inspect what is on offer – and from whom.

Looking for Africa’s Dubai. A growing number of African governments want to replicate the economic success of Dubai and Singapore and become commercial gateways into the continent. They must do more than follow the rush to create shiny new infrastructure. Investors expect long-term political stability, basic services to work, skilled workforces and a promising market. With so many countries looking to become new African hubs, competition will bring over capacity; some players will fall by the wayside.

Russia and the US President-elect. Donald Trump’s leadership is likely to herald a more pragmatic relationship between the US and Russia in 2017, at least in the short-term; it may include an effort to ease sanctions and dampen cyber hostilities. But in the longer term, a transactional, business partner style approach is unlikely to survive the reality of the diplomatic complexities and deep-rooted animosity in the US-Russia relationship.

Mexico and the new US administration. Will the US President-elect deliver on his campaign rhetoric and build a border wall with Mexico, deport an estimated 5.7 million illegal Mexican migrants, add tariffs of up to 35% on goods manufactured in Mexico by US companies and renegotiate or pull out of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)? Early signals indicate a willingness to be more moderate. Statements on deportations now focus mainly on convicted felons, while the talk is of using fences instead of a wall along the border. Mexico may also be on the cusp of becoming a far more stable place for business because of its clamp down on corruption. In June 2016 Congress passed legislation to implement a new National Anti-Corruption System (NAS) which starts in 2017 and will be a key issue when Mexico goes to the polls in 2018.

Brazil and Argentina opening to trade. Brazil and Argentina will welcome 2017 as a fresh start. Both look poised to leave economic recession and following recent leadership changes they expect to bolster their economies with foreign trade. They are negotiating (with Paraguay and Uruguay) a bilateral trade agreement with the EU, and are likely to approve an initiative that allows members of the Southern Common Market (Mercosur) trade bloc to pursue similar talks independently. But trade openness is being challenged in many parts of the world, including the US and the EU.

Five more years of Xi Jinping’s China. The Communist Party of China (CPC) will hold its five-yearly national congress in late 2017, marking the end of President Xi Jinping’s first term in power and almost certainly the start of his second. The broader transition beneath him is very important, especially as China enters a more difficult and uncertain era of its development – one where growth is slowing and must be driven less by sheer mobilisation of resources, and more by their efficient use. In spite of the challenges, the outlook for foreign companies remains quite strong relative to many countries.

Thailand: Royal succession problems. Political instability in Thailand will increase in 2017 following the death of revered King Bhumibol Adulyadej in October 2016, the succession of Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn, a deeply polarising figure, and general elections scheduled late in the year. The contest for power, the security environment and the regulatory landscape has the potential to disrupt business operations on many fronts.

MENA: Top five drivers of risk in 2017

The big black swan of 2017 for the Middle East region will be a potential unravelling of the nuclear deal with Iran as a result of changes in US foreign policy under President Trump. While we consider that to remain unlikely, this would have significant security and business implications for the region by pushing Iran back into aggressive foreign policy and into commercial isolation.

Under our main scenario which provides for continuity of the nuclear deal beyond 2017, the top five likely drivers of risks to international businesses in the Middle East are:

Geopolitics: Shifting global geopolitical relationships will be mirrored by a realignment of foreign policy alliances and priorities of major players in the Middle East. Countries such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Qatar and Iran will look to build or consolidate bridges with China, Japan, India and/or Russia to hedge against the uncertainty surrounding US’ and Europe’s engagement in the region. Such policy realignments are likely to play out in the commercial sphere when it comes to major project awards and bilateral trade agreements.

Fiscal consolidation: Efforts to reduce government spending in response to low oil prices will continue to affect economic growth and dampen public investment levels across the region. They will also drive regulatory risk – particularly rises in local taxes and changes to local content regulations, as well as risks of non-payment and contract frustration. Reform efforts are also likely to trigger localised labour and/or social unrest against governments and businesses in North Africa, particularly in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco.

Push for FDI: Most countries in the region are putting in place plans and strategic visions to increase their attractiveness to foreign investors in an effort to diversify their economies and secure growth in sectors other than oil and gas. While these efforts may be successful in non-strategic sectors such as education, healthcare and e-commerce might, they are unlikely to succeed in other major sectors, such as energy or telecommunications, where prevailing statists trends and a desire for government interference will likely limit the extent of privatisation and liberalisation.

Weakening of Islamic State: The collapse of IS territory is likely to prompt a global exodus of foreign fighters. As IS falls, many will be killed in battle, some captured trying to escape and others recruited into other groups – including rival al-Qaida affiliate Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (JFS) or continuing to operate in weak governance areas, such as the Sinai in Egypt, as well as parts of Libya, Syria and Iraq. The rest will most likely return to their home countries in Western Europe, Russia, North Africa or the GCC and will try to imbue local extremist networks in their home countries with their experience and capability. While in Iran and the GCC this trend is unlikely to trigger any significant increase in the threat of attacks, countries such as Tunisia, Morocco, Lebanon and Jordan may face higher challenges to contain returning IS fighters.

Cyber: The conflict in Syria and the broader complex gepolitical situation in the Middle East is likely to have a significant impact on the regional cyber threat landscape in the coming year. In particular, Iran has continued to develop its capabilities and lags behind only Israel in the region in terms of its ability to conduct disruptive cyber attacks on geopolitical rivals, though other states are also seeking to develop these tools for their own arsenals. In 2017, Iran and these emerging actors are likely to use their capabilities to conduct plausibly deniable data-wiping attacks in its rivals, using activist groups to claim credit for the incidents so as to complicate the victims’ response. These attacks are particularly likely to target governmental bodies, symbolic targets and elements of critical national infrastructure in rival states.

Economy

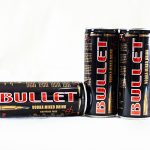

Champion Breweries Concludes Bullet Brand Portfolio Acquisition

By Aduragbemi Omiyale

The acquisition of the Bullet brand portfolio from Sun Mark has been completed by Champion Breweries Plc, a statement from the company confirms.

This marks a transformative milestone in the organisation’s strategic expansion into a diversified, pan-African beverage platform.

With this development, Champion Breweries now owns the Bullet brand assets, trademarks, formulations, and commercial rights globally through an asset carve-out structure.

The assets are held in a newly incorporated entity in the Netherlands, in which Champion Breweries holds a majority interest, while Vinar N.V., the majority shareholder of Sun Mark, retains a minority stake.

Bullet products are currently distributed in 14 African markets, positioning Champion Breweries to scale beyond Nigeria in the high-growth ready-to-drink (RTD) alcoholic and energy drink segments.

This expansion significantly broadens the brewer’s addressable market and strengthens its revenue base with an established, profitable portfolio that already enjoys strong brand recognition and consumer loyalty across multiple markets.

“The successful completion of our public equity raises, together with the formal close of the Bullet acquisition, marks a defining moment for Champion Breweries.

“The support we received from both existing shareholders and new investors reflects strong confidence in our long-term strategy to build a diversified, high-growth beverage platform with pan-African scale.

“Our focus now is on disciplined execution, integration, and delivering sustained value across markets,” the chairman of Champion Breweries, Mr Imo-Abasi Jacob, stated.

Through this transaction, Champion Breweries is expected to achieve enhanced foreign exchange earnings, expanded distribution leverage across African markets, integrated supply chain efficiencies, portfolio diversification into high‑growth consumer beverage categories, and strengthened presence in the RTD and energy drink segments.

The acquisition accelerates Champion Breweries’ transition from a regional brewing business to a multi-category consumer platform with continental reach.

Bullet Black is Nigeria’s leading ready-to-drink alcoholic beverage, while Bullet Blue has built a strong presence in the energy drink category across several African markets.

Economy

M-KOPA Nigeria Plans Expansion to Edo, Others After N231bn Credit Milestone

By Adedapo Adesanya

Emerging market fintech firm, M-KOPA, has announced plans to deepen its reach in Nigeria to the South South and South East regions, starting with Edo this year, after providing N231 billion in credit to over 1 million customers in the country.

The firm released its first Nigeria-focused Impact Report, which showed that Nigeria is M-KOPA’s fastest-growing market and fastest to reach the milestone.

Since its foray into the Nigerian market in 2019, M-KOPA has been working to dismantle barriers to financial inclusion by providing flexible smartphone financing and digital financial tools that align with how people in the informal economy earn and manage their money.

It operates in six states in the country, including Lagos, Ogun, and Oyo, among others.

The report highlights the company’s contribution to income generation, digital inclusion and economic opportunity for Every Day Earners across the country.

The report showed that M-KOPA has enabled 290,000 first-time smartphone users, while 56 per cent of agents accessed their first income opportunity through the platform.

It showed high income and livelihood gains among its users, with about 77 per cent of customers leveraging smartphones or digital loans obtained through the platform to generate income, indicating that access to financed devices is directly supporting micro-entrepreneurial activity and informal sector productivity.

Furthermore, 75 per cent of users report higher earnings since gaining access to M-KOPA’s services, suggesting measurable improvements in personal revenue streams. On the distribution side, 99 per cent of agents disclose increased earnings, reflecting positive spillover effects across the company’s value chain.

In addition, 81 per cent of long-term customers state that their household expenses have improved, pointing to enhanced financial stability and better consumption smoothing over time.

Speaking on the report, Mr Babajide Duroshola, General Manager, M-KOPA Nigeria, said, “Nigeria represents extraordinary potential, and we’re proud that it has become M-KOPA’s fastest-growing market. Our Impact Report shows that when Every Day Earners gain access to the right digital and financial tools, they use them to create stability and long-term progress for their families. This is about access that unlocks opportunity and sustained prosperity.”

On its expansion plans Nigeria-wide, the M-KOPA helmsman said, “Many of the states we are considering are already similar to the ones we are currently in proximity… So, there is proximity and similarity between these states, and that’s what we are going to do, starting with Edo.”

He noted that as M-KOPA Nigeria continues to expand, the focus remains on ensuring more everyday earners gain access to the digital and financial tools they need to build resilient, prosperous futures in Nigeria’s rapidly digitising economy.

Economy

Tinubu Okays Extension of Ban on Raw Shea Nut Export by One Year

By Aduragbemi Omiyale

The ban on the export of raw shea nuts from Nigeria has been extended by one year by President Bola Tinubu.

A statement from the Special Adviser to the President on Information and Strategy, Mr Bayo Onanuga, on Wednesday disclosed that the ban is now till February 25, 2027.

It was emphasised that this decision underscores the administration’s commitment to advancing industrial development, strengthening domestic value addition, and supporting the objectives of the Renewed Hope Agenda.

The ban aims to deepen processing capacity within Nigeria, enhance livelihoods in shea-producing communities, and promote the growth of Nigerian exports anchored on value-added products, the statement noted.

To further these objectives, President Tinubu has authorised the two Ministers of the Federal Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment, and the Presidential Food Security Coordination Unit (PFSCU), to coordinate the implementation of a unified, evidence-based national framework that aligns industrialisation, trade, and investment priorities across the shea nut value chain.

He also approved the adoption of an export framework established by the Nigerian Commodity Exchange (NCX) and the withdrawal of all waivers allowing the direct export of raw shea nuts.

The President directed that any excess supply of raw shea nuts should be exported exclusively through the NCX framework, in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Additionally, he directed the Federal Ministry of Finance to provide access to a dedicated NESS Support Window to enable the Federal Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment to pilot a Livelihood Finance Mechanism to strengthen production and processing capacity.

Shea nuts, the oil-rich fruits from the shea tree common in the Savanna belt of Nigeria, are the raw material for shea butter, renowned for its moisturising, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. The extracted butter is a principal ingredient in cosmetics for skin and hair, as well as in edible cooking oil. The Federal Government encourages processing shea nuts into butter locally, as butter fetches between 10 and 20 times the price of the raw nuts.

The federal government said it remains committed to policies that promote inclusive growth, local manufacturing and position Nigeria as a competitive participant in global agricultural value chains.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn