Feature/OPED

Conflicts/Insecurity in Africa and Achike Chudi’s Solution

By Jerome-Mario Utomi

It was at a recent gathering organised by one of the Catholic churches in Lagos aimed at creating new awareness to assist parishioners to keep abreast with the fuelling factors and possible steps that will cushion the socioeconomic impact of nagging insecurity in the country.

The gathering had as a theme Heightening Insecurity in the Country: Exploring Ways to Mitigate Hardship, with Achike Chudi, a public affairs commentator and Vice President Joint Action Front (JAF) as the keynote speaker.

On that day, at that time and in that place, while Achike examined the multiple layers of formal and informal political leadership in post-colonial Africa, the primary holders, controllers and distributors of power and resources in a particular institution and/or territory, he argued that contemporary African leaders operate in an environment constrained by colonial legacies and instability and submitted that leadership in Nigeria/Africa as a continent is characteristically neo-patrimonial, featuring presidentialism, clientelism, the use of state resources and the centralization of power.

Separate from providing sustainable roadmaps/solutions to the nagging challenge of conflict/insecurity in Nigeria and Africa as a whole, there are in fact more inherent reasons why we must not allow Achike’s latest intervention to go with political winds.

First, he started by stating without doubt that the problem of the Nigerian nation is rooted in our past, just as the foundation of every state is in the education of its youth and the beauty of a building traced to the construction of its foundation that will stand the test of time.

He used carefully prepared power points, properly framed arguments, vivid evidence and emotional match with the audience, to demonstrate that the way in which a government or institution at an international or societal level addresses conflict between individuals, groups or nations can determine whether the parties to the conflict will resort to violence.

He argued that State weakness can create the conditions for violent conflict, noting that political institutions that are unable to manage differing group interests peacefully, to provide adequate guarantees of group protection, or to accommodate growing demands for political participation, can fracture societies. There is a degree of consensus that there is a U-shaped relationship between levels of democracy and the likelihood of violent conflict, he concluded.

On the causes of conflict and insecurity, Achike has this to say; “there is no single cause of conflict. Rather, conflict is context-specific, multi-causal and multidimensional and can result from a combination of the following factors. Political and institutional factors: weak state institutions, elite power struggles and political exclusion, breakdown in social contract and corruption, identity politics.

“Socioeconomic factors: inequality, exclusion and marginalization, absence or weakening of social cohesion, poverty. Resource and environmental factors: greed, scarcity of national resources often due to population growth leading to environmental insecurity, unjust resource exploitation.”

Each of these factors he argued may constitute a cause, dynamic and/or impact of conflict. New issues will arise during the conflict which perpetuates the conflict. Identifying and understanding the interactions between various causes, dimensions, correlates and dynamics of conflict – and the particular contexts in which conflict arises, is essential in determining potential areas of intervention; and designing appropriate approaches and methods for conflict prevention, resolution and transformation

While mature democracies are able to manage tensions peacefully through democratic inclusion, stark autocracies are able to repress violence and manage conflict through force. The most vulnerable states are those in a political transition. Uncertainty and collective fears of the future, stemming from state weakness, clientelism and indiscriminate repression may result in the emergence of armed responses by marginalized groups and nationalist, ethnic or other populist ideologies.

Is democratization the best way to promote peace?

He again argues that the world would probably be safer if there were more mature democracies but, in the transition to democracy, countries become more aggressive and war-prone. The international community should be realistic about the dangers of encouraging democratization where the conditions are unripe. The risk of violence increases if democratic institutions are not in place when mass electoral politics are introduced.

Away from the usefulness of democracy to what causes ethnic conflict, and why does it escalate? He responded thus; intense ethnic conflict is usually caused by collective fears for the future. It presents a framework for understanding the origins and management of ethnic conflict and recommends how the international community can intervene more effectively.

Three key factors contribute to the development of ethnic conflict: Information failure, when individuals or groups misrepresent or misinterpret information about other groups; Problems of credible commitment, when one group cannot credibly reassure another that it will not renege on or exploit a mutual agreement; and Security dilemmas when one or more disputing parties has an incentive to use pre-emptive force. When these factors take hold, groups become apprehensive, the state weakens, and conflict becomes more likely.

The domination of access to state structures and resources by any one leader, group or political party to the exclusion of others exacerbates social divisions. It may provide incentives for excluded leaders to mobilise groups to protest and engage in violent rebellion. In contrast, inclusive elite bargains that seek to address social fragmentation and integrate a broad coalition of key elites can reduce the chances of violent rebellion.

Continuing, he said; a social contract is a framework of rules that govern state-society relations and the distribution of resources, rights and responsibilities in an organised society. How a government spends public revenue, regardless of whether it comes from taxes or from natural resources, is significant.

If it spends it equitably on social welfare and satisfying basic needs, conflict is less likely to occur if these resources are spent judiciously than when appropriated for corrupt or fractional purposes. Corruption undermines public trust in government, deters domestic and foreign investment, exacerbates inequalities in wealth and increases socio-economic grievances.

Equally, the inability of states to provide basic services, including justice and security, to all its citizens reduces state legitimacy and trust in state institutions, weakening or breaking the social contract.

Still, on the factor promoting insecurity/conflict, he told the bewildered gathering that in some cases, ruling groups may resort to violence to prolong their rule and maintain opportunities for corruption. This can in turn provoke violent rebellion by marginalized groups. In other situations, research has found that “buying off” opposition groups and belligerents may facilitate transitions to peace – The North and the importation of belligerents in anticipation of the 2015 elections

Moving away from elite power struggles and political exclusion, Achike raised another point relevant to the present security temperatures in the country and Africa.

In his words, colonialism and liberation struggles in Africa, the Middle East and Asia have left various legacies, including divisive and militarized politics and fierce struggles for power and land. Post-liberation leaders in some countries have sustained these dynamics, retaining power through neo-patrimonial networks, state capture, militarization and coercion.

Studies have shown that in some cases, they have promoted ideologies of ‘Us versus Them’, excluding and marginalising other groups. The domination of access to state structures and resources by any one leader, group or political party to the exclusion of others exacerbates social divisions. It may provide incentives for excluded leaders to mobilise groups to protest and engage in violent rebellion. In contrast, inclusive elite bargains that seek to address social fragmentation and integrate a broad coalition of key elites can reduce the chances of violent rebellion.

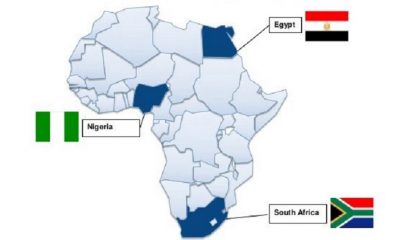

Sub-Saharan Africa, he said is the world’s most conflict-intensive region. But why have some African states experienced civil war, while others have managed to maintain political stability? This paper argues that the ability of post-colonial states in Sub-Saharan Africa to maintain political stability depends on the ability of the ruling political parties to overcome the historical legacy of social fragmentation.

On the way forward, he observed that creating inclusive elite bargains can bring stability while exclusionary elite bargains give rise to trajectories of civil war, promotion of inclusive political settlements. Most importantly, the nation must facilitate the further goals of (i) addressing causes of conflict and building resolution mechanisms; (ii) developing state survival functions; and (iii) responding to public expectations. Support across all four of these interrelated areas is necessary to help create a positive peace- and state-building dynamic, he concluded.

What does all this say to us in Nigeria? The answer in my view is in the womb of time.

Jerome-Mario Utomi is the Programme Coordinator (Media and Public Policy), Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA), Lagos. He could be reached via je*********@***oo.com/08032725374.

Feature/OPED

Pension for Informal Workers Nigeria: Bridging the Pension Gap

***The Case for Informal Sector Pensions in Nigeria

***A Crucial National Conversation

By Timi Olubiyi, PhD

In Nigeria today, the phrase “pension” evokes many different mixed reactions. For many civil servants and people in the corporate world, it conjures a bit of hope, but for the majority in the informal sector, who are in the majority in Nigeria, it is bleak. Millions of Nigerians are facing old age without any financial security due to a lack of retirement plans and a stable pension plan. Particularly, the millions who operate in markets, corner shops, transportation, agriculture, and loads of the nano and micro scale enterprises operators are without pension plans or retirement hope.

From the observation of the author and available records, staggering around 90 per cent of Nigeria’s workforce operates in the informal economy. Yet current pension coverage for this group is virtually non-existent. As observed, the absence of meaningful pension participation by this class of worker reinforces the vulnerability, intensifies poverty among older people, and puts pressure on families who are ill-equipped to shoulder the burden.

The significance of having a pension plan for informal workers in Nigeria, given the large number of people in that sector and the high level of unemployment and underemployment, cannot be overstated. As it is deeply connected to sustenance and the level of poverty in the country. Pension for informal workers in Nigeria is not just a technical policy matter; it is a story about dignity, security, and whether a lifetime of hard work ends in rest or in desperation.

Nigeria’s pension system, primarily structured around the Contributory Pension Scheme (CPS) managed by the National Pension Commission (PenCom), has made significant progress for formal sector employees, yet the large portion of the informal workforce which are traders, artisans, okada riders, small-scale farmers, domestic workers, and gig economy participants who drive the real engine of the economy.

Though the Micro Pension Plan (MPP) was launched in 2019, which is intended to provide a voluntary contributory framework for informal workers, its uptake has been underwhelming; after several years, only a fraction of the millions targeted have enrolled, and far fewer contribute actively. One big reason for this is that, unlike formal workers who receive regular salaries and have employers who deduct and remit pension contributions, informal workers face irregular incomes, a lack of documentation, limited financial literacy, and deep mistrust of government institutions, making traditional pension models ill-suited for their realities.

Moreso the informal worker most times live on day-to-day income. For instance, a motorcycle rider in Lagos who earns ₦14,000 on a good day but must pay for fuel, bike maintenance, police “settlements,” and family expenses, how can he realistically commit to a monthly pension contribution when his income fluctuates wildly? So, the Micro Pension Plan for the informal sector participation will remain low due to poor awareness, complex processes, lack of tailored contribution flexibility, and limited trust.

To truly make pensions work for informal workers, Nigeria must rethink the system from the ground up, designing it around the lived realities of its people rather than forcing them into rigid formal-sector structures. First, the government should introduce a co-contributory model where the state matches a percentage of informal workers’ savings, similar to what is practised in some European countries, turning pension contributions into a powerful incentive rather than a burdensome obligation.

Second, digital technology must be leveraged aggressively—mobile-based pension platforms linked to BVN or NIN could allow daily, weekly, or micro-contributions as small as ₦100, integrating seamlessly with fintech apps like OPay, Paga, or bank USSD services so that saving becomes as easy as buying airtime.

Third, automatic enrollment through cooperatives, trade unions, market associations, and transport unions could significantly expand coverage, with opt-out rather than opt-in mechanisms to counter human inertia.

Fourth, financial literacy campaigns in local languages via radio, community leaders, and religious institutions are essential to rebuild trust and demonstrate that pensions are not a “government scam” but a personal safety net.

Fifth, Nigeria should consider a universal social pension for elderly citizens who never participated in formal or informal schemes, modelled after systems in countries like Denmark and the Netherlands, ensuring that no Nigerian dies in poverty simply because they worked outside formal structures.

Sixth, investment strategies for pension funds must prioritise both security and development—allocating a portion to infrastructure projects that create jobs, improve power supply, and stimulate economic growth while maintaining prudent risk management.

Seventh, inflation protection should be built into pension payouts so that retirees’ purchasing power is not eroded by Nigeria’s volatile economy.

Eighth, the system must be inclusive of women, who dominate the informal sector yet often lack property rights or formal identification, by simplifying documentation requirements and providing gender-sensitive outreach.

Ninth, limited emergency withdrawal options could be introduced—strictly regulated—to help contributors handle crises without abandoning the system entirely.

Finally, transparency and accountability are non-negotiable; regular public reporting, independent audits, and user-friendly dashboards would strengthen confidence that contributions are safe and growing. If Nigeria can blend its innovative spirit with lessons from global best practices—combining Denmark’s social security ethos, Singapore’s savings discipline, and Canada’s inclusivity—it could transform the lives of millions of informal workers who currently face retirement with fear rather than hope.

Imagine Aisha, years from now, closing her market stall not in exhaustion and anxiety but in calm assurance that her pension will cover her basic needs; imagine Tunde hanging up his helmet knowing he can afford healthcare and shelter; imagine Ngozi harvesting not just crops but the fruits of a lifetime of secure savings. The suspense that hangs over the future of Nigeria’s informal workers can be resolved, but only if policymakers act boldly, creatively, and compassionately—because a nation that allows its hardest workers to age in poverty is a nation that undermines its own prosperity, while a nation that secures their retirement builds not just pensions, but peace.

Hope comes from innovation. Fintech-powered pension models that allow small, frequent contributions similar to informal savings associations like esusu offer ways to integrate pensions into existing savings cultures. Making pension contributions compatible with mobile money and agent networks could drastically reduce barriers to entry. Hope comes from public education. Building financial literacy campaigns, partnering with community leaders, marketplaces, trade associations, and digital platforms can help shift perceptions. A pension should be understood not as a distant bureaucratic programme, but as future self-insurance and dignity

The significance of having a pension plan for informal workers in Nigeria, given its large informal sector and high level of unemployment and underemployment, cannot be overstated, as it is deeply connected to social stability, economic sustainability, poverty reduction, and national development.

First, from a social protection and human dignity perspective, a pension plan for informal workers is critical because it provides a safety net for old age. Nigeria’s informal sector includes traders, artisans, mechanics, tailors, hairdressers, okada riders, gig workers, domestic workers, small-scale farmers, and street vendors, many of whom work hard throughout their lives but have no formal retirement benefits. Without a pension, these individuals often become completely dependent on their children, relatives, or charity in old age, which can strain families and increase intergenerational poverty. A well-structured pension system ensures that ageing informal workers can maintain a basic standard of living, access healthcare, and avoid extreme deprivation, thereby preserving their dignity and reducing elderly vulnerability.

Second, from an economic stability and poverty reduction standpoint, pensions play a crucial role in reducing old-age poverty. Nigeria already struggles with high poverty levels, and a large proportion of elderly citizens without income support exacerbates this problem. When informal workers lack pension savings, they continue working well into old age, often in physically demanding jobs, which reduces productivity and increases health risks. A pension system allows for smoother retirement transitions, reduces reliance on welfare, and ensures that older citizens remain consumers rather than economic burdens, thereby sustaining economic activity.

Third, pensions for informal workers are significant for financial inclusion and savings culture. Many Nigerians in the informal sector operate primarily in cash and have limited engagement with formal financial institutions. A pension plan tailored to informal workers, especially one integrated with mobile money and digital platforms, can encourage regular saving, improve financial literacy, and bring millions of people into the formal financial system. This, in turn, strengthens Nigeria’s overall financial sector and increases the pool of domestic savings available for investment in infrastructure, businesses, and development projects.

Fourth, the significance is evident in reducing dependence on government emergency support. Currently, the Nigerian government often has to intervene with ad-hoc social assistance programs, especially during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation shocks, or economic downturns. If informal workers had functional pension savings, they would be better able to absorb economic shocks in retirement without relying heavily on government aid, reducing fiscal pressure on the state.

Fifth, pensions for informal workers contribute to intergenerational equity and family stability. In Nigeria, many elderly parents depend on their working children for survival, which places financial strain on younger generations who may already be struggling with unemployment, housing costs, and education expenses. A pension system reduces this burden, allowing younger Nigerians to invest in their own futures rather than being trapped in a cycle of supporting ageing relatives without external assistance.

Sixth, from a national development perspective, including informal workers in the pension system strengthens Nigeria’s long-term economic planning. Pension funds represent large pools of capital that can be invested in critical sectors such as housing, energy, transportation, and manufacturing. If millions of informal workers contribute even in small amounts, this could significantly expand Nigeria’s pension fund assets, providing stable, long-term financing for development projects that create jobs and stimulate growth.

Seventh, pensions for informal workers are important for gender equity, because women dominate many informal occupations in Nigeria, such as petty trading, market vending, tailoring, and caregiving roles. These women often have lower lifetime earnings, limited access to formal employment, and fewer assets. A targeted informal sector pension scheme can protect elderly women from destitution and reduce gender-based economic inequality in old age.

Eighth, the significance is also linked to public trust and governance. A transparent, accessible, and reliable pension system for informal workers can strengthen citizens’ trust in government institutions. Many informal workers currently distrust government programs due to past corruption, failed schemes, or poor implementation. A well-functioning pension plan that delivers real benefits would demonstrate that the state values all citizens, not just formal sector employees.

Lastly, given Nigeria’s demographic reality of a large and growing population, failing to integrate informal workers into a pension framework poses serious long-term risks. As life expectancy increases, the number of elderly Nigerians will rise significantly in the coming decades. Without a structured pension system for informal workers, Nigeria could face a severe old-age crisis characterised by mass poverty, social unrest, and increased pressure on healthcare and social services.

In summary, having a pension plan for informal workers in Nigeria is significant because it promotes social security, reduces poverty, enhances financial inclusion, supports economic stability, eases intergenerational burdens, strengthens national development, promotes gender equity, builds public trust, and prepares the country for its ageing population. For a nation where the majority of workers are informal, excluding them from pension coverage is not just an oversight; it is a major structural weakness that must be urgently addressed for Nigeria’s long-term prosperity and social cohesion.

Feature/OPED

Revived Argungu International Fishing Festival Shines as Access Bank Backs Culture, Tourism Growth

The successful hosting of the 2026 Argungu International Fishing Festival has spotlighted the growing impact of strategic public-private partnerships, with Access Bank and Kebbi State jointly reinforcing efforts to promote cultural heritage, tourism development, and local economic growth following the globally attended celebration in Argungu.

At the grand finale, Special Guest of Honour, Mr Bola Tinubu, praised the festival’s enduring national significance, describing it as a powerful expression of unity, resilience, and peaceful coexistence.

“This festival represents a remarkable history and remains a powerful symbol of unity, resilience, and peaceful coexistence among Nigerians. It reflects the richness of our culture, the strength of our traditions, and the opportunities that lie in harnessing our natural resources for national development. The organisation, security arrangements, and outlook demonstrate what is possible when leadership is purposeful and inclusive.”

State authorities noted that renewed institutional backing has strengthened the festival’s global appeal and positioned it once again as a major tourism and cultural platform capable of attracting international visitors and investors.

“Argungu has always been an iconic international event that drew visitors from across the world. With renewed partnerships and stronger institutional support, we are confident it will return to that global stage and expand opportunities for our people through tourism, culture, and enterprise.”

Speaking on behalf of Access Bank, Executive Director, Commercial Banking Division, Hadiza Ambursa, emphasised the institution’s long-standing commitment to supporting initiatives that preserve heritage and create economic opportunities.

“We actively support cultural development through initiatives like this festival and collaborations such as our partnership with the National Theatre to promote Nigerian arts and heritage. Across states, especially within the public sector space where we do quite a lot, we work with governments on priorities that matter to them. Tourism holds enormous potential, and while we have supported several hotels with expansion financing, we remain open to working with partners interested in developing the sector further.”

Reports from the News Agency of Nigeria indicated that more than 50,000 fishermen entered the historic Matan Fada River during the competition. The overall winner, Abubakar Usman from Maiyama Local Government Area, secured victory with a 59-kilogram catch, earning vehicles donated by Sokoto State and a cash prize. Other top contestants from Argungu and Jega also received vehicles, motorcycles and monetary rewards, including sponsorship support from WACOT Rice Limited.

Recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, the festival blends traditional fishing contests with boat regattas, durbar processions, performances, and international competitions, drawing visitors from across Nigeria and beyond.

With the 2026 edition concluded successfully, stakeholders say the strengthened collaboration between government and private-sector partners signals a renewed era for Argungu as a flagship cultural tourism destination capable of driving inclusive growth, preserving tradition, and projecting Nigeria’s heritage on the world stage.

Feature/OPED

$214Bn Missing, Institutions Silent: Is Accountability Dead in Nigeria?

By Blaise Udunze

Between 2010 and 2026, a staggering $214 billion, approximately N300 trillion in public funds, has been reported as missing, unaccounted for, diverted, unrecovered, irregularly spent, or trapped in non-transparent fiscal structures across Nigeria’s public institutions.

That figure is not speculative but a conservative estimate of unaccounted funds. It is drawn from audit reports, legislative probes, civil society litigation, executive directives, and investigative findings spanning more than a decade. If it is to go by the accurate figure, the true national loss is likely higher but difficult to quantify precisely due to data gaps, overlapping figures, and incomplete audits.

The challenge is that in many of the most prominent cases, prosecutions have stalled, hearings have dragged without resolution, investigations have gone cold, and no defining jail terms have etched accountability into Nigeria’s institutional memory. The irony is that the number is historic, the silence is louder. And the economic damage is cumulative.

The pattern stretches from the oil sector to social investment programmes, from the Nigeria Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) interventions to ministry-level expenditures. In 2014, between $10.8 billion and $20 billion in unremitted oil revenues linked to the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation triggered national outrage. Under the then CBN governor, Lamido Sanusi, who warned that persistent oil revenue leakages were making exchange rate stability “extremely difficult.” He cautioned that without full remittances, the alternative would be currency devaluation and financial instability. This concern spans the 2010 to 2013 oil revenue period. That warning proved prophetic.

This is because, years later, the lack of transparency in the oil industry did not disappear, but rather it festered like cancer. It further led to the elongated audit queries, which have continued to trail the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited, including unremitted revenues, questioned deductions, and management fee structures under the Petroleum Industry Act. With an extraordinary move aimed at blocking revenue leakages at source, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has recently issued an Executive Order suspending certain deductions and directing direct remittance of taxes, royalties, and profit oil into the Federation Account, which involves the reassessment of NNPC’s 30 per cent management fee and 30 per cent frontier exploration deduction under the Petroleum Industry Act.

Such presidential intervention underscores the scale of concern, which means that Nigeria cannot afford a structural lack of transparency in its most strategic revenue sector. But oil is only one chapter.

The Central Bank of Nigeria has faced some of the most far-reaching audit alarms in recent years. In suit number FHC/ABJ/CS/250/2026, the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) is asking the Federal High Court to compel the CBN to account for N3 trillion in allegedly missing or diverted public funds. The Auditor-General’s 2025 report cited failures to remit over N1.44 trillion in operating surplus to the Consolidated Revenue Fund, over N629 billion paid to “unknown beneficiaries” under the Anchor Borrowers’ Programme, and more than N784 billion in overdue, unrecovered intervention loans.

There were also N125 billion in questioned intervention expenditures, irregular contract variations exceeding N9 billion, and procurement gaps running into hundreds of billions. The Auditor-General repeatedly recommended recovery and remittance. No date has been fixed for the hearing. Meanwhile, Nigeria continues to borrow.

Elsewhere, the House of Representatives has launched a probe into over N30 billion recovered during investigations into the National Social Investment Programme Agency (NSIPA). The funds, reportedly frozen during investigation, have not been remitted back into the Treasury Single Account, stalling poverty-alleviation schemes like TraderMoni and FarmerMoni. Millions of vulnerable Nigerians remain exposed while lawmakers search for money already “recovered.” The irony is staggering as funds are found, but programmes remain frozen.

A top discovery recently that put the nation on red alert was made by the Senate committee, which claimed to have found N210 trillion in financial irregularities in NNPC accounts between 2017 and 2023, including unaccounted receivables and accrued expenses. A critical concern is that, as of early 2026, this has sparked commentary but no clear prosecutions.

Only recently, in the power sector, SERAP has urged the President to probe alleged missing or unaccounted N128 billion at the Federal Ministry of Power and the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading Plc. Of concern is that despite the enormous funds channelled in this sector, Nigeria’s chronic electricity instability persists, even as billions meant to stabilise the grid face audit scrutiny.

Across MDAs, audit reports between 2017 and 2022 flagged trillions in unsupported expenditures, unremitted taxes, unauthorised payments, and statutory liabilities never recovered. These sums are dizzying and are also alarming; N300 billion here, N149 billion there, N3.403 trillion across agencies, N30 trillion-plus Treasury discrepancies raised at the Senate level.

Individually, they shock. Collectively, they define a structural pattern. And patterns shape economies.

Nigeria operates with structural fiscal deficits and also lives with them routinely and comfortably. Expenditure persistently exceeds revenue. When public funds disappear, fail to be remitted, or are trapped outside constitutional channels, the deficit widens. The government must borrow to fill gaps created not only by low revenue, but by revenue leakage.

Debt servicing now consumes a disproportionate share of federal revenue. Borrowing meant for capital projects increasingly finances recurrent obligations. The country shifts from borrowing to build to borrowing to survive. Every missing naira compounds tomorrow’s liability.

The Treasury Single Account (TSA) was designed to plug such leakages. It consolidated government revenues under Section 80 of the Constitution into a unified framework. International financial institutions commended it as a landmark reform. Yet even today, the Minister of Finance, Wale Edun, has admitted that substantial government funds remain outside the TSA and outside the CBN’s consolidated visibility. Until August 1, 2024, he revealed, the federal government could not fully see its own balance sheet at the apex bank. That admission should alarm any serious economy.

Fiscal lack of transparency constrains planning. It undermines monetary coordination. It weakens debt sustainability projections. It distorts policy responses. And when systems are in flux, money vanishes more easily.

Changing or weakening the TSA in such an environment would be catastrophic. Transitions create windows of vulnerability. Old accounts close. New accounts open. Reconciliation’s lag. Ghost contractors reappear. Double payments slip through.

Albeit, the government must learn to tread with caution as Nigeria’s institutional bandwidth is already strained by simultaneous tax reforms, exchange-rate adjustments, subsidy removal, and fiscal restructuring. One truth that cannot be argued is that layering additional structural upheaval onto fragile systems risks revenue loss that the country cannot afford. Investors are watching.

Credit markets evaluate not just numbers but institutional consistency. A nation that abandons or weakens its most credible fiscal reform sends a destabilising signal. Stability lowers borrowing costs. Institutional drift raises them. But beyond markets lies the human cost.

N300 trillion represents roads not built, power plants not completed, irrigation systems not funded, schools not modernised, and hospitals not equipped. It represents jobs not created and industries not catalysed. It represents stalled productivity and deferred growth.

When intervention loans remain unrecovered, agricultural output suffers. When power sector funds are unaccounted for, electricity remains unstable. When social investment funds are frozen, poverty deepens.

Inflation then compounds the pain. Revenue gaps push borrowing. Borrowing pressures, interest rates and by extension, liquidity misalignment fuel price instability. Citizens pay through higher food costs, transport fares, and rent. The poor pay first. The middle class erodes quietly.

Perhaps most corrosive is the trust deficit. When audit queries fade without visible accountability, tax morale weakens. Compliance declines. Cynicism hardens. A nation cannot modernise where trust in fiscal integrity is fragile.

Section 15(5) of the Constitution requires the abolition of corrupt practices. Financial Regulations mandate a surcharge and referral to anti-corruption agencies where public officers fail to account for funds. The Fiscal Responsibility Act empowers citizens to enforce compliance to ensure that government officials follow fiscal rules. But enforcement defines seriousness.

Nigeria’s problem is not a lack of audit findings. It is the distance between findings and finality.

Nations do not collapse overnight due to a lack of funds. They drift. Infrastructure decays incrementally. Debt rises gradually. Growth slows subtly. Confidence erodes quietly. Then one day, stagnation feels permanent. $214 billion (N300 trillion), sixteen years of recurring audit alarms. Few conclusive accountability outcomes are proportionate to the scale. Truly, the consequences have been less strong. For the same reason, the country witnessed President Tinubu nominating ex-NIA boss Ayodele Oke as ambassador despite a $43 million loot in an Ikoyi apartment.

See the research breakdown of some of the audit figures that reveal staggering sums as enumerated above:

– $10.8 billion and separately $20 billion in unaccounted oil revenues at the NNPC in 2014

– $1.1 billion controversial Malabu Oil and Gas oil deal in 2015

– $2.2 billion arms procurement irregularities in 2015

– N3.4 billion from IMF COVID-19 financing flagged in a 2020 audit.

– N149.36 billion, N37.2 billion, and multiple irregular MDA expenditures in 2020 alone.

– N300 billion cited in public audit concerns in 2017.

– N210 trillion in financial irregularities uncovered, N103 trillion in ‘accrued expenses’, and another N107 trillion in unaccounted ‘receivables’ (2017 -2023).

– N57 billion Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs – (2021)

– N3 trillion and N1.44 trillion flagged in 2022 audit issues involving the Central Bank of Nigeria.

– Nearly N630 billion under the Anchor Borrowers Programme is reportedly unrecovered.

– N784 billion in overdue intervention loans flagged.

– Over N3.403 trillion unaccounted for across federal MDAs between 2019 and 2021.

– Roughly 30 trillion+ in Treasury Single Account and Consolidated Revenue Fund discrepancies raised at the Senate level.

– N500 billion in unremitted oil revenues between 2019 and 2024.

– N80 billion tied to alleged fictitious contracts in the Accountant-General’s office.

– N69.9 billion in uncollected statutory tax liabilities.

– Billions more in unauthorised or undocumented expenditures across ministries.

The institutions differ. The years differ. The audit language differs. The pattern does not.

Nigeria’s economic future will not be determined solely by how much oil it produces, how many reforms it announces, or how many executive orders it signs. It will be determined by whether every naira earned enters the Federation Account transparently, whether every intervention loan is tracked and recovered, whether every surplus is remitted constitutionally, and whether every diversion carries consequences. Revenue generation matters. Revenue protection is destiny. Because when government funds go missing, nations do not stand still. They move backwards.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn