World

Besides Mali, Russia Keenly Interest in Five-Nation Sahel Group

By Kester Kenn Klomegah

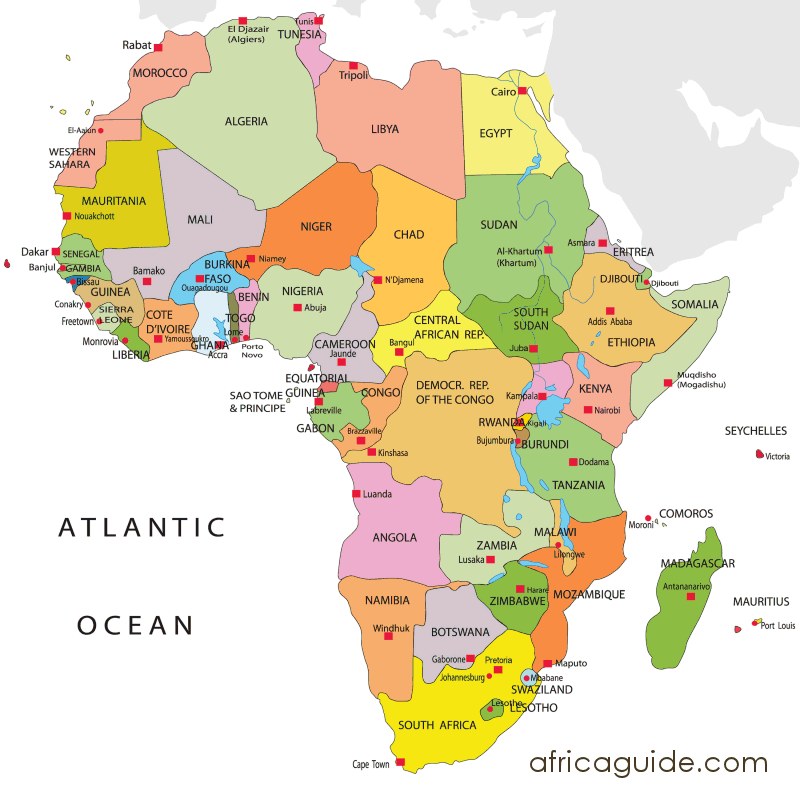

Russia’s alleged involvement in the political change on August 18 in Mali, a former French colony with the fractured economy and breeding field for armed Islamic jihadist groups (some of which are reportedly aligned with Al Qaeda and ISIS), demonstrates the first drastic step towards penetrating into the G5 Sahel in West Africa. The G5 Sahel are Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger.

Despite this widely published allegation, Moscow officially said it was seriously concerned about the developments in Bamako and further urged “all Malian public and political forces to settle the situation peacefully at the negotiating table”.

Russian Foreign Ministry said on its website that on August 21, at the invitation of the leaders of the military group, who seized power in Mali, Russian Ambassador in Bamako Igor Gromyko met with the leader of the National Committee for the Salvation of the People, Colonel Assimi Goita, at the military base in the town of Katiа located not far from the capital.

The statement said: “At his own initiative, Assimi Goita informed the Russian Ambassador about the reasons that prompted the military to remove President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita and the Malian Government from power, as well as about the committee’s priority steps to restore order in the country and set up the operation of government bodies.

“The leaders of the National Committee for the Salvation of the People held similar meetings with the ambassadors of several other countries, including China and France.”

According to several reports, Ibrahim Keita was overthrown following mass protests against his rule over deep-rooted corruption, mismanagement of the economy and a dispute over legislative elections.

In addition to socio-economic problems, Mali is now facing the task of protecting its territorial integrity and combating the terrorist threat.

Internal unrest in the country has greatly undermined Malians’ ability to contribute to the collective efforts of the Sahara-Sahel countries, including the G5 Sahel group of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger, which is focused on combating terrorism.

While updating the implications of the recent coup, in Mali on the entire G5 Sahel region, it is important to know more about the leaders of the coup, and the foreign countries and players who might have aided the army to topple the democratic and legitimate government of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. The Economist article of August 19, titled What next for Mali?, which is enclosed here:

The narratives are that the coup led by Malick Diaw and Sadio Camara, two army colonels who hold top positions at the Kati military base, are reportedly very close friends. The two colonels spent most of this year training in Russia before returning to Mali and to topple the government, which could imply that most probably they might have hatched and organized the coup whilst in Russia (read), and this implied that the Russians might have known about their political plans in Mali.

Many experts say Russia has its own distinctive style and approach, set out to battle against exploitation of resources, or better still what is often phrased “the scramble for resources” in Africa.

Besides dealing with the French, Russia is keenly interested in the uphill fight against “neo-colonial tendencies” exhibited by the US (read), EU (read), and Chinese (read) interests and influence in Africa.

As already showcased in Mali, experts told IDN that as Russia looks for “strategic allies” in the continent, so working to remove African leaders loyal to former colonial masters fits squarely into Russia’s renewed interest and strategy in Africa.

Research Professor Irina Filatova at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow explains to IDN that media reports have linked the developments to Russia, that however “people who are now in power will be friendlier with Russia than the previous government. The Russians are not seriously interested in democratic institutions, they are interested in people who are close to it.”

In the short term or better still in the long term, it is hard to be optimistic for Mali, among the fragile countries in the Sahel, especially the importance of seeking stability, building the infrastructure and improving the economy. The region is experiencing the spread of Islamic extremist insurgency and rapidly-eroding state legitimacy.

On the other hand, Mali’s challenges are almost the same throughout Africa: deep-seated corruption, heightened nepotism, ethnic violence and economic malaise. The African leaders lust for power in spite of bad governance. Civil society platforms have meanwhile called for deep reforms, especially on electoral laws and the administrative machinery in Mali.

Mali, home to nearly 20 million people, is a landlocked country located on rivers Senegal and Niger in West Africa. As a former French colony, it persistently faces serious development challenges primarily due to its landlocked position and it is the eighth-largest country in Africa.

Over the years, reform policies have had little impact on the living standards, majority highly impoverished in the country. As a developing country, it ranks at the bottom of the United Nations Development Index (2018 report).

Russia is broadening its geography of diplomacy covering poor African countries and especially fragile states that need Russia’s military assistance.

Niger, for example, has been on its radar. Russia, meanwhile, sees some potential there – as a possible gateway into the Sahel. In order to realize this, Russia has been working on the official visit for Mahamadou Issoufou who has been the President of Niger since April 2011. Before that, Issoufou was the Prime Minister of Niger from 1993 to 1994.

Last year, on September 19, when Niger’s Foreign Minister Kalla Ankourao paid a working visit to Moscow, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov pointed to two basic facts.

The first was “the Russian Federation looks forward to stepping up cooperation in all spheres, and international matters and crisis resolution on the African continent are also very much relevant for us.”

The second was that “the meeting has special significance since in the next two years Niger is a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council. Russia and Niger hope to work closely together within this important international body.”

Since Niger holds a non-permanent seat at the UN Security Council in 2020-2021, Sergey Lavrov and Kalla Ankourao have been focusing on in-depth discussions on matters relating to the fight against terrorism and extremism in the context of collective efforts to root out these threats, particularly within the G5 Sahel region in Africa.

As Russia pushes to strengthen its overall profile in the G5 Sahel region, in July 2019, Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov held talks with the President of Burkina Faso, Christian Kaboré and further discussed military-technical cooperation with the Minister of National Defense and Veteran Affairs, Moumina Sheriff Sy. He also had business talks with Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Burkina Faso, Alpha Barry, and Vice-President of the National Assembly of Burkina Faso, K. Traore.

Last year in August, Bogdanov attended the inauguration of Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Ghazouani. The President of Mauritania was elected on Jun 22, 2019. Both discussed ways for strengthening the existing relations. Moscow and Nouakchott look for additional dynamics to the development of mutually beneficial cooperation in various fields.

According to the official information posted to the ministry’s website, Bogdanov described his meetings “providing the impetus to explore opportunities for effective collaboration in the Sahel region.”

Vedomosti, a Russian daily Financial and Business newspaper, reported that Russia is interested in offering Mali and the Sahel countries military equipment. The Malian government and Russian state-owned arms trader Rosoboronexport could soon sign contracts on the delivery of Russian-made combat and transport helicopters, armoured personnel carriers, small arms and ammunition to the African country, the Vedomosti newspaper reported.

The Russian weapons requested by Mali’s government will be given to its soldiers in the north of the country, where the Malian Armed Forces, as well as soldiers from France and a number of African states, are fighting Islamist militants, a Rosoboronexport source told Vedomosti.

“The French side is highly unlikely to object to equipping the Malian Army with Russian-made weapons because these weapons are more familiar to the Malian Army, where some 7,000 people serve in the Land Forces and another 400 in the Air Force,” the source said. It also that the fight “against international terrorist groups, whose growing activity is seen in the Sahara Sahel region.”

Russian Foreign Ministry has explained in a statement released on its website, that Russia’s military-technical cooperation with African countries is primarily directed at settling regional conflicts and preventing the spread of terrorist threats and to fight the growing terrorism in the continent. Worth noting here that Russia, in its strategy on Africa is reported to be also looking into building military bases in the continent.

Over the past years, strengthening military-technical cooperation has been part of the foreign policy of the Russian Federation. Russia has signed bilateral military-technical cooperation agreement nearly with all African countries. Researchers say further that it plans to build military bases as this article explicitly reported, among others.

Edward Lozansky, President of the American University in Moscow and professor of World Politics at Moscow State University, told IDN in an email that “there has not been too much information about Russia’s activities in Africa, but the Western media is saturated with the scary stories about Russia’s efforts to bolster its presence in at least 13 countries across Africa by building relations with existing rulers, striking military deals, and grooming a new generation of leaders and undercover agents.”

Further to the narratives, Russia has now embarked on fighting “neo-colonialism” which it considers as a stumbling block on its way to regain a part of the Soviet-era multifaceted influence in Africa. Russia has sought to convince Africans over the past years of the likely dangers of neocolonial tendencies perpetrated by the former colonial countries and the scramble for resources on the continent. But all such warnings largely seem to fall on deaf ears as African leaders choose development partners with funds to invest in the economy.

Experts suspected that Russia’s plan to bring about regime change in Mali could see Russia-friendly new leaders taking over the country from the French-friendly President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita and his government, thereby dealing a severe blow to French influence and interests not just in Mali but throughout the Sahel region.

Research Professor Irina Filatova at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow explains to IDN that “Russia’s influence in the Sahel has been growing just as French influence and assistance has been dwindling, particularly in the military sphere. It is for the African countries to choose their friends, but it would be better to deal directly with the government, than with (mercenaries of the Russian) Wagner, which group, whose connection with the government was barely recognized.”

In very particular cases, she unreservedly suggested: “If they wanted the Russians to come and fight Islamist groups, it would be much better to ask the government to send regular troops. Wagner’s vigilantes are not responsible to anybody, and the Russian government may refuse to take any responsibility for whatever they do in case something goes wrong.”

While the African Union (AU), regional blocs and African leaders remain indifferent, Russia has expressed concern and takes the task to fight “neocolonialism” in Africa. It has sought to convince Africans over the past years of the likely dangers of neocolonial tendencies perpetrated by the former colonial countries and the scramble for resources on the continent. But all such warnings largely seem to fall on deaf ears as African leaders choose development partners with funds to invest in the economy.

But these have different interpretations as African leaders still show loyalty to their former colonizers. Neocolonialism can be seen as a new form of domination, plunder and exploitation using clandestine and economic statecraft.

Of course, there could be some hints or pointers to neocolonial tendencies, but such claims should be levelled on case by case basis, and there has to be concrete evidence to suggest that way, explains Dr. Frangton Chiyemura, a lecturer in International Development at the School of Social Sciences and Global Studies, Open University in the United Kingdom.

In his objective opinion, Chiyemura further believes “as there is no free lunch in the world, African countries should enter into partnerships based on their strategic interests and an understanding of what the partners can provide or deliver.”

Secondly, every African country should do a comprehensive evaluation of the structure and, the terms and conditions of their engagements with foreign powers. By so doing, this will eliminate the chances for the emergence of claims of neocolonialism. Instead of extending the blame to someone elsewhere, Africa needs to do its homework especially on the implementation and monitoring aspects of the deals. Africa has some of the best regulations and standards, but the problem lies in implementation and monitoring, the development expert suggested in an e-mailed discussion with IDN.

Interestingly, Sochi hosted the first summit in October 2019 devoted to interaction between Russia and Africa. That event opened up a new page in the history of Russia’s relations with African countries, President Vladimir Putin told the gathering: “We are ready to continue working together to strengthen mutually beneficial cooperation. But we are also aware of the host of problems facing Africa that need to be settled.”

In his view, “this new stage and this new quality of our relations should be based on common values. We are at one in our support for the values of justice, equality and respect for the rights of African states to, independently choose their future. It is within this framework that we will continue to coordinate our positions at international platforms and joint efforts in the interests of stability on the African continent.”

Russia-Africa relations is based on long-standing traditions of friendship and solidarity created when the Soviet Union supported the struggle of the peoples of Africa against colonialism, racism and apartheid, protected their independence and sovereignty, and helped establish statehood, and build the foundations of the national economy, according to historical documents available at the website of Kremlin.

The African Union, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and foreign organizations such as the European Union (EU) and the United Nations (UN) have requested a quick transition to a civilian government. They further urged that efforts are taken to resolve outstanding issues relating to sustainable development and observing strictly principles of democracy.

All these organizations have utterly denounced the coup. What follows now will be negotiations over the transitional arrangements and the timetable for new elections. This will not be straightforward. Although the opposition was united in their demand for Keita’s resignation there is little consensus on what to do next, while the UN Security Council and ECOWAS are divided on how to respond beyond initial condemnation.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, spoke out against the coup as well saying that the situation should be returned to normal under the elected civilian government in Mali. In addition, an official statement was issued by the AU Commission Chair on the situation in Mali. It says in part: “The AU Chairperson calls on the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the United Nations and the entire international community to combine collective efforts to oppose any use of force as a means to end the political crisis in Mali.”

Beyond condemning developments in Mali, the African Union and the regional blocs have to consistently remind African leaders to prioritize sustainable development goals and understand the basic principle through which they were elected: the electorate and the people. That makes it utterly necessary to engage them in development decision-making processes and use available resources to improve their communities – these are the drivers of the expected lasting change needed in Africa.

Kester Kenn Klomegah writes frequently about Russia, Africa and BRICS. This article was first and originally published by IndepthNews.

World

AfBD, AU Renew Call for Visa-Free Travel to Boost African Economic Growth

By Adedapo Adesanya

The African Development Bank (AfDB) and the African Union have renewed their push for visa-free travel to accelerate Africa’s economic transformation.

The call was reinforced at a High-Level Symposium on Advancing a Visa-Free Africa for Economic Prosperity, where African policymakers, business leaders, and development institutions examined the need for visa-free travel across the continent.

The consensus described the free movement of people as essential to unlocking Africa’s economic transformation under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The symposium was co-convened by AfDB and the African Union Commission on the margins of the 39th African Union Summit of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa.

The participants framed mobility as the missing link in Africa’s integration agenda, arguing that while tariffs are falling under AfCFTA, restrictive visa regimes continue to limit trade in services, investment flows, tourism, and labour mobility.

On his part, Mr Alex Mubiru, Director General for Eastern Africa at the African Development Bank Group, said that visa-free travel, interoperable digital systems, and integrated markets are practical enablers of enterprise, innovation, and regional value chains to translate policy ambitions into economic activity.

“The evidence is clear. The economics support openness. The human story demands it,” he told participants, urging countries to move from incremental reforms to “transformative change.”

Ms Amma A. Twum-Amoah, Commissioner for Health, Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development at the African Union Commission, called for faster implementation of existing continental frameworks.

She described visa openness as a strategic lever for deepening regional markets and enhancing collective responses to economic and humanitarian crises.

Former AU Commission Chairperson, Ms Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, reiterated that free movement is central to the African Union’s long-term development blueprint, Agenda 2063.

“If we accept that we are Africans, then we must be able to move freely across our continent,” she said, urging member states to operationalise initiatives such as the African Passport and the Free Movement of Persons Protocol.

Ghana’s Trade and Industry Minister, Mrs Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare, shared her country’s experience as an early adopter of open visa policies for African travellers, citing increased business travel, tourism, and investor interest as early dividends of greater openness.

The symposium also reviewed findings from the latest Africa Visa Openness Index, which shows that more than half of intra-African travel still requires visas before departure – seen by participants as a significant drag on intra-continental commerce.

Mr Mesfin Bekele, Chief Executive Officer of Ethiopian Airlines, called for full implementation of the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM), saying aviation connectivity and visa liberalisation must advance together to enable seamless travel.

Regional representatives, including Mr Elias Magosi, Executive Secretary of the Southern Africa Development Community, emphasised the importance of building trust through border management and digital information-sharing systems.

Ms Gabby Otchere Darko, Executive Chairman of the Africa Prosperity Network, urged governments to support the “Make Africa Borderless Now” campaign, while tourism campaigner Ras Mubarak called for more ratifications of the AU Free Movement of Persons protocol.

Participants concluded that achieving a visa-free Africa will require aligning migration policies, digital identity systems, and border infrastructure, alongside sustained political commitment.

World

Nigeria Exploring Economic Potential in South America, Particularly Brazil

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this interview, Uche Uzoigwe, Secretary-General of NIDOA-Brazil, discusses the economic potential in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners for the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN). Follow the discussion here:

How would you assess the economic potential in the South American region, particularly Brazil, for the Federal Republic of Nigeria? What investment incentives does Nigeria have for potential corporate partners from Brazil?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, my response to the questions regarding the economic potentials in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners would be as follows:

Brazil, as the largest economy in South America, presents significant opportunities for the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The country’s diverse economy is characterised by key sectors such as agriculture, mining, energy, and technology. Here are some factors to consider:

- Natural Resources: Brazil is rich in natural resources like iron ore, soybeans, and biofuels, which can be beneficial to Nigeria in terms of trade and resource exchange.

- Growing Agricultural Sector: With a well-established agricultural sector, Brazil offers potential collaboration in agri-tech and food security initiatives, which align with Nigeria’s goals for agricultural development.

- Market Size: Brazil boasts a large consumer market with a growing middle class. This represents opportunities for Nigerian businesses looking to export goods and services to new markets.

- Investment in Infrastructure: Brazil has made significant investments in infrastructure, which could create opportunities for Nigerian firms in construction, engineering, and technology sectors.

- Cultural and Economic Ties: There are historical and cultural ties between Nigeria and Brazil, especially considering the African diaspora in Brazil. This can facilitate easier business partnerships and collaborations.

In terms of investment incentives for potential corporate partners from Brazil, Nigeria offers several attractive incentives for Brazilian corporate partners, including:

- Tax Incentives: Various tax holidays and concessions are available under the Nigerian government’s investment promotion laws, particularly in key sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and technology.

- Repatriation of Profits: Brazil-based companies investing in Nigeria can repatriate profits without restrictions, thus enhancing their financial viability.

- Access to the African Market: Investment in Nigeria allows Brazilian companies to access the broader African market, benefiting from Nigeria’s membership in regional trade agreements such as ECOWAS.

- Free Trade Zones: Nigeria has established free trade zones that offer companies the chance to operate with reduced tariffs and fewer regulatory burdens.

- Support for Innovation: The Nigerian government encourages innovation and technology transfer, making it attractive for Brazilian firms in the tech sector to collaborate, particularly in fintech and agriculture technology.

- Collaborative Ventures: Opportunities exist for joint ventures with local firms, leveraging local knowledge and networks to navigate the business landscape effectively.

In conclusion, fostering a collaborative relationship between Nigeria and Brazil can unlock numerous economic opportunities, leading to mutual growth and development in various sectors. We welcome potential Brazilian investors to explore these opportunities and contribute to our shared economic goals.

In terms of this economic cooperation and trade, what would you say are the current practical achievements, with supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, I would highlight the current practical achievements in economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil, alongside the supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA.

Here are some key points:

Current Practical Achievements

- Increased Bilateral Trade: There has been a notable increase in bilateral trade volume between Nigeria and Brazil, particularly in sectors such as agriculture, textiles, and technology. Recent trade agreements and discussions have facilitated smoother trade relations.

- Joint Ventures and Partnerships: Successful joint ventures have been established between Brazilian and Nigerian companies, particularly in agriculture (e.g., collaboration in soybean production and agricultural technology) and energy (renewables, oil, and gas), demonstrating commitment to mutual development.

- Investment in Infrastructure Development: Brazilian construction firms have been involved in key infrastructure projects in Nigeria, contributing to building roads, bridges, and facilities that enhance connectivity and economic activity.

- Cultural and Educational Exchange Programs: Programs facilitating educational exchange and cultural cooperation have led to strengthened ties. Brazilian universities have partnered with Nigerian institutions to promote knowledge transfer in various fields, including science, technology, and arts.

Supporting Strategies

- Strategic Trade Dialogue: NIDOA has initiated regular dialogues between trade ministries of both nations to discuss trade barriers, potential markets, and cooperative opportunities, ensuring both countries are aligned in their economic goals.

- Investment Promotion Initiatives: Targeted initiatives have been established to promote Brazil as an investment destination for Nigerian businesses and vice versa. This includes showcasing success stories at international trade fairs and business forums.

- Capacity Building and Technical Assistance: NIDOA has offered capacity-building programs focused on enhancing Nigeria’s capabilities in agriculture and technology, leveraging Brazil’s expertise and sustainable practices.

- Policy Advocacy: Continuous advocacy for favourable trade policies has been a key focus for NIDOA, working to reduce tariffs and promote economic reforms that facilitate investment and trade flows.

Systemic Engagement

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Engaging the private sector through PPPs has been essential in mobilising resources for development projects. NIDOA has actively facilitated partnerships that leverage both public and private investments.

- Trade Missions and Business Delegations: Organised trade missions to Brazil for Nigerian businesses and vice versa, allowing for direct engagement with potential partners, fostering trust and opening new channels for trade.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: NIDOA implements a rigorous monitoring and evaluation framework to assess the impact of various initiatives and make necessary adjustments to strategies, ensuring effectiveness in achieving economic cooperation goals.

Through these practical achievements, supporting strategies, and systemic engagement, NIDOA continues to play a pivotal role in enhancing economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil. By fostering collaboration and leveraging shared resources, we aim to create a sustainable and mutually beneficial economic environment that promotes growth for both nations.

Do you think the changing geopolitical situation poses a number of challenges to connecting businesses in the region with Nigeria, and how do you overcome them in the activities of NIDOA?

The changing geopolitical situation indeed poses several challenges for connecting businesses in the South American region, particularly Brazil, with Nigeria. These challenges include trade tensions, shifting alliances, currency fluctuations, and varying regulatory environments. Below, I will outline some of the specific challenges and how NIDOA works to overcome them:

Current Challenges

- No Direct Flights: This challenge is obviously explicit. Once direct flights between Brazil and Nigeria become active, and hopefully this year, a much better understanding and engagement will follow suit.

- Trade Restrictions and Tariffs: Increasing trade protectionism in various regions can lead to higher tariffs and trade barriers that hinder the movement of goods between Brazil and Nigeria.

- Currency Volatility: Fluctuations in the value of currencies can complicate trade agreements, pricing strategies, and overall financial planning for businesses operating in both Brazil and Nigeria.

- Different regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements in both countries can create challenges for businesses aiming to navigate these systems efficiently.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Changes in global supply chains due to geopolitical factors may disrupt established networks, impacting businesses relying on imports and exports between the two nations.

Overcoming Challenges through NIDOA.

NIDOA actively engages in discussions with both the Brazilian and Nigerian governments to advocate for favourable trade policies and agreements that reduce tariffs and improve trade conditions. This year in October, NIDOA BRAZIL holds its TRADE FAIR in São Paulo, Brazil.

What are the popular sentiments among the Nigerians in the South American diaspora? As the Secretary-General of the NIDOA, what are your suggestions relating to assimilation and integration, and of course, future perspectives for the Nigerian diaspora?

As the Secretary-General of NIDOA, I recognise the importance of understanding the sentiments among Nigerians in the South American diaspora, particularly in Brazil.

Many Nigerians in the diaspora take pride in their cultural roots, celebrating their heritage through festivals, music, dance, and culinary traditions. This cultural expression fosters a sense of community and belonging.

While many individuals embrace their new environments, they often face challenges related to cultural differences, language barriers, and social integration, which can lead to feelings of isolation.

Many express optimism about opportunities in education, business, and cultural exchange, viewing their presence in South America as a chance to expand their horizons and contribute to economic activities both locally and back in Nigeria.

Sentiments regarding acceptance vary; while some Nigerians experience warmth and hospitality, others encounter prejudice or discrimination, which can impact their overall experience in the host country. NIDOA BRAZIL has encouraged the formation of community organisations that promote networking, cultural exchange, and social events to foster a sense of belonging and support among Nigerians in the diaspora. There are currently two forums with over a thousand Nigerian members.

Cultural Education and Awareness Programs: NIDOA BRAZIL organises cultural education programs that showcase Nigerian heritage to local communities, promoting mutual understanding and appreciation that can facilitate smoother integration.

Language and Skills Training: NIDOA BRAZIL provides language courses and skills training programs to help Nigerians, especially students in tertiary institutions, adapt to their new environment, enhancing communication and employability within the host country.

Engaging in Entrepreneurship: NIDOA BRAZIL supports the entrepreneurial spirit among Nigerians in the diaspora by facilitating access to resources, mentorship, and networks that can help them start businesses and create economic opportunities.

Through its AMBASSADOR’S CUP COMPETITION, NIDOA Brazil has engaged students of tertiary institutions in Brazil to promote business projects and initiatives that can be implemented in Nigeria.

NIDOA BRAZIL also pushes for increased tourism to Brazil since Brazil is set to become a global tourism leader in 2026, with a projected 10 million international visitors, driven by a post-pandemic rebound, enhanced air connectivity, and targeted marketing strategies.

Brazil’s tourism sector is poised for a remarkable milestone in 2026, as the country expects to welcome over 10 million international visitors—surpassing the previous record of 9.3 million in 2025. This expected surge represents an ambitious leap, nearly doubling the country’s foreign-arrival numbers within just four years, a feat driven by a combination of pent-up global demand, strategic air connectivity improvements, and a highly targeted marketing campaign.

World

African Visual Art is Distinguished by Colour Expression, Dynamic Form—Kalalb

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this insightful interview, Natali Kalalb, founder of NAtali KAlalb Art Gallery, discusses her practical experiences of handling Africa’s contemporary arts, her professional journey into the creative industry and entrepreneurship, and also strategies of building cultural partnership as a foundation for Russian-African bilateral relations. Here are the interview excerpts:

Given your experience working with Africa, particularly in promoting contemporary art, how would you assess its impact on Russian-African relations?

Interestingly, my professional journey in Africa began with the work “Afroprima.” It depicted a dark-skinned ballerina, combining African dance and the Russian academic ballet tradition. This painting became a symbol of cultural synthesis—not opposition, but dialogue.

Contemporary African art is rapidly strengthening its place in the world. By 2017, the market was growing so rapidly that Sotheby launched its first separate African auction, bringing together 100 lots from 60 artists from 14 foreign countries, including Algeria, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, and others. That same year during the Autumn season, Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris hosted a major exhibition dedicated to African art. According to Artnet, sales of contemporary African artists reached $40 million by 2021, a 434% increase in just two years. Today, Sotheby holds African auctions twice a year, and in October 2023, they raised $2.8 million.

In Russia, this process manifests itself through cultural dialogue: exhibitions, studios, and educational initiatives create a space of trust and mutual respect, shaping the understanding of contemporary African art at the local level.

Do you think geopolitical changes are affecting your professional work? What prompted you to create an African art studio?

The international context certainly influences cultural processes. However, my decision to work with African themes was not situational. I was drawn to the expressiveness of African visual language—colour, rhythm, and plastic energy. This theme is practically not represented systematically and professionally in the Russian art scene.

The creation of the studio was a step toward establishing a sustainable platform for cultural exchange and artistic dialogue, where the works of African artists are perceived as a full-fledged part of the global cultural process, rather than an exotic one.

To what extent does African art influence Russian perceptions?

Contemporary African art is gradually changing the perception of the continent. While previously viewed superficially or stereotypically, today viewers are confronted with the depth of artistic expression and the intellectual and aesthetic level of contemporary artists.

Portraits are particularly impactful: they allow us to see not just an abstract image of a “continent,” but a concrete personality, character, and inner dignity. Global market growth data and regular auctions create additional trust in African contemporary art and contribute to its perception as a mature and valuable movement.

Does African art reflect lifestyle and fashion? How does it differ from Russian art?

African art, in my opinion, is at its peak in everyday culture—textiles, ornamentation, bodily movement, rhythm. It interacts organically with fashion, music, interior design, and the urban environment. The Russian artistic tradition is historically more academic and philosophical. African visual art is distinguished by greater colour expression and dynamic form. Nevertheless, both cultures are united by a profound symbolic and spiritual component.

What feedback do you receive on social media?

Audience reactions are generally constructive and engaging. Viewers ask questions about cultural codes, symbolism, and the choice of subjects. The digital environment allows for a diversity of opinions, but a conscious interest and a willingness to engage in cultural dialogue are emerging.

What are the key challenges and achievements of recent years?

Key challenges:

- Limited expert base on African contemporary art in Russia;

- Need for systematic educational outreach;

- Overcoming the perception of African art as exclusively decorative or ethnic.

Key achievements:

- Building a sustainable audience;

- Implementing exhibition and studio projects;

- Strengthening professional cultural interaction and trust in African

contemporary art as a serious artistic movement.

What are your future prospects in the context of cultural diplomacy?

Looking forward, I see the development of joint exhibitions, educational programs, and creative residencies. Cultural diplomacy is a long-term process based on respect and professionalism. If an artistic image is capable of uniting different cultural traditions in a single visual space, it becomes a tool for mutual understanding.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn