World

Russia Contributes 35% of Global Arms Export to Africa—Envoy

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

Russia has been accused of not doing enough for the growth of Africa, especially since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

It was observed that Russia-African diplomacy had been marked by several bilateral agreements that are yet to be implemented.

According to official documents, 92 agreements worth a total of $12.5 billion were signed during the symbolic African leaders’ gathering in late October 2019, and Russia has done little to implement them since then.

The joint declaration is a comprehensive document that outlines the key objectives and tasks required to elevate the entire relationship to a new qualitative level.

Long before the summit, there were mountains of promises and pledges that were never fulfilled. Several meetings of various bilateral intergovernmental commissions have taken place in both Moscow and Africa.

According to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, over 170 Russian companies and organizations submitted 280 proposals relating to various projects and businesses in Africa.

As Russia prepares for the next summit, which will be held in St. Petersburg in July 2023, African leaders have indicated their willingness to actively participate, at the very least, to listen to rousing speeches, sign more new agreements, and finally pose for group photos.

However, many experts and top African diplomats question the substance of discussing additional opportunities and effective efforts to build and strengthen Russia-African relations.

The revival of Russia-Africa relations must address existing challenges while also taking a results-oriented approach to pressing African issues. Taking into account the views and opinions expressed by African politicians, businesspeople, experts, and diplomats about the situation in Africa is one of them.

In practice, while Russia reaffirms its desire to return to Africa, it has yet to demonstrate a visible long-term commitment to collaborating with appropriate institutions to advance sustainable development across the continent.

Professor Abdullahi Shehu, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Federal Republic of Nigeria to the Russian Federation with concurrent accreditation to the Republic of Belarus, delivered a lecture on “Africa-Russia Relations: Past, Present, and Future” to young diplomats and students of the Diplomatic Academy of the Russian Federation in mid-October.

Ambassador Shehu talked a lot about African history. He focused on the effects of the times before, during, and after contact with European powers and the neo-colonization of African states that happened after that.

He also discussed Africa’s relations with the Soviet Union, which began in large part after the independence of several African states in the 1960s. He emphasized the contributions to Africa’s decolonization struggle, as well as the numerous areas of cooperation that have existed between Africa and Russia over the years.

Professor Shehu emphasized the existence of several bilateral agreements with African countries, saying between 2015 and 2019, Russia and African countries signed a total of 20 bilateral military cooperation agreements. Many Russian companies, including Lukoil, Gasprom, Rosatom, and Restec, are in Nigeria, Egypt, Angola, Algeria, and Ethiopia’s energy and power industries.

But on the other hand, Russia has performed dismally in Africa’s energy sector and many other important economic spheres over the years.

“Unfortunately, due to Rosneft’s lack of interest in doing business in Africa, these agreements have not materialized. Furthermore, Russia’s Rosatom has also signed nuclear energy agreements with 18 African countries, including Nigeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Rwanda, to meet those countries’ power needs but has not been successful in building nuclear plants in Africa.

“Despite the tidal wave of new Africa-Russian relations, there are still obstacles, as well as new economic conditions and geopolitical realities. Acceptance of these new realities is critical in order to properly manage Africa’s expectations from Russia, at least in the short term,” the envoy said.

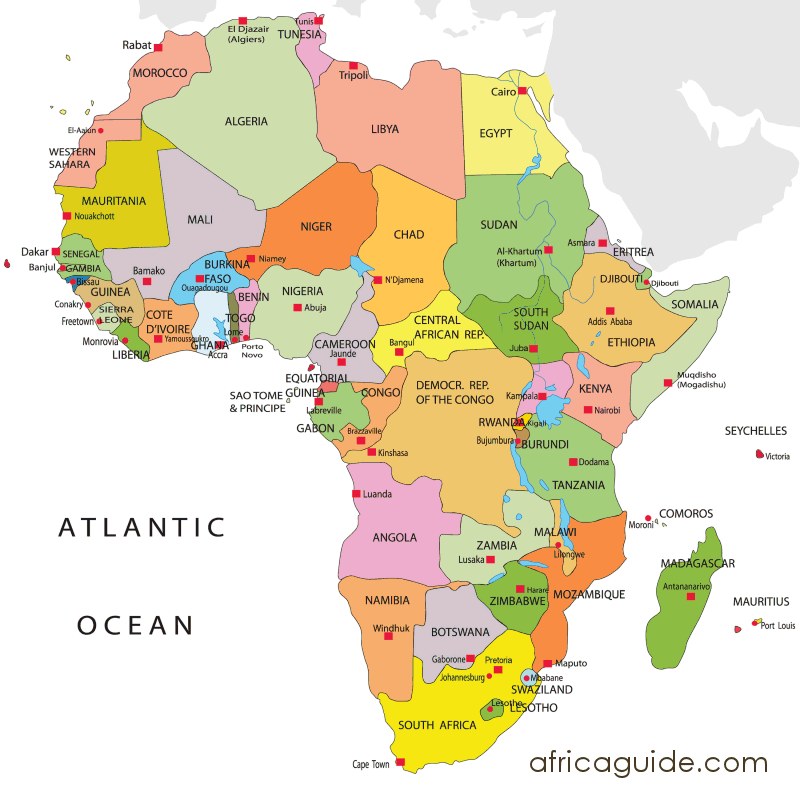

On the indiscriminate export of arms and military equipment, Ambassador Shehu stated, “However, Russia’s increasing export of arms to the African continent may exacerbate insecurity and instability, as well as increase the level of crime and criminal proclivity. So, it is in Russia’s strategic interest to be very picky about which African countries it sells weapons to. The deployment of private Russian mercenary groups and other private military groups in African countries is of particular concern and strategic importance to Africa.”

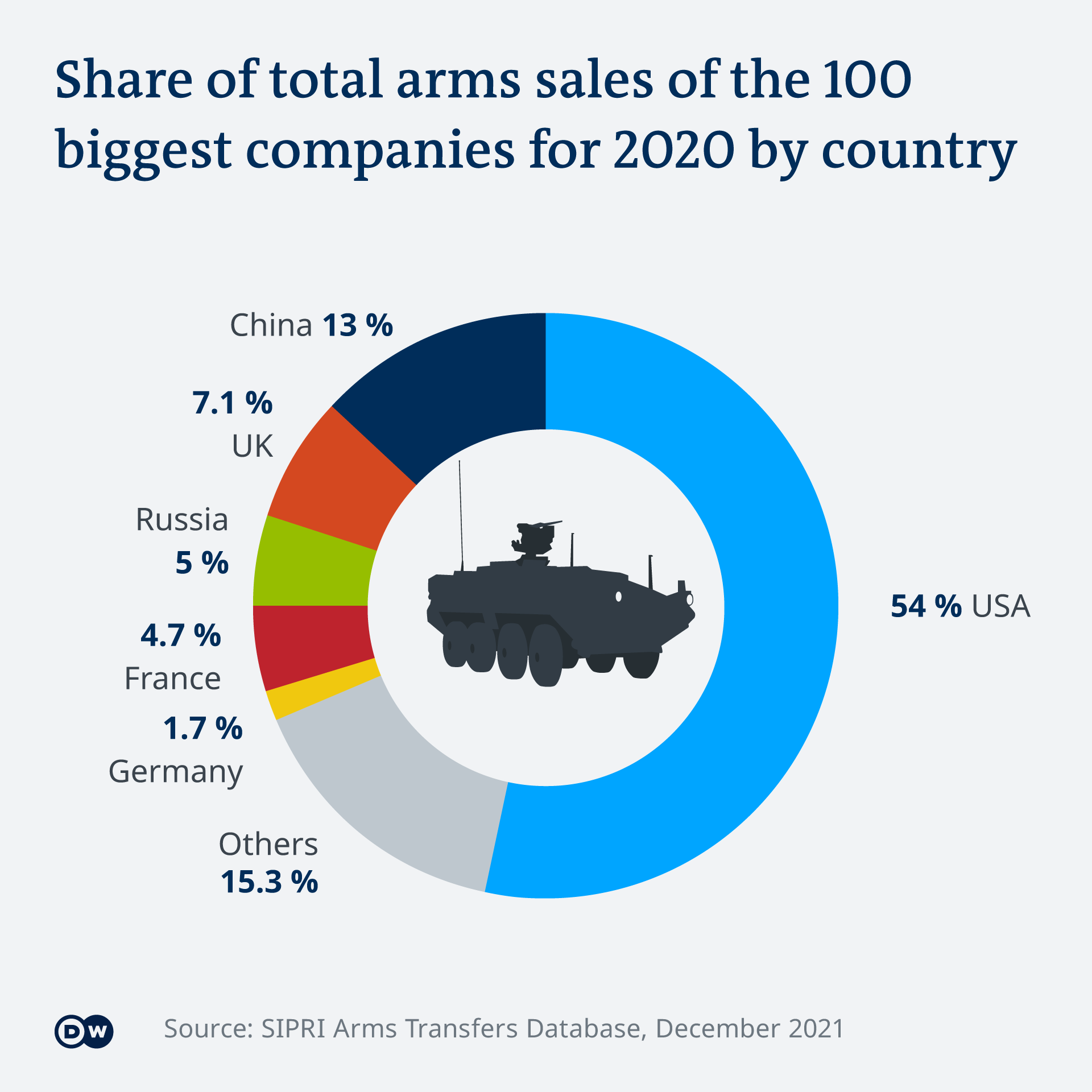

Support for Africa’s democratic institutions and agencies will lead to a more stable Africa, which is in Russia’s overall long-term interest and positive image rather than immediate short-term economic and financial gain, he said in his lecture, adding that Russia contributes approximately 35% of global arms export to the African region.

Given the difficulties that most African countries face in providing adequate power and energy, the number of Memorandums of Understanding (MOU) signed by Rosatom, Russia’s nuclear power company, with at least 14 African countries, is encouraging. What will be more significant, however, is the extent to which the MOUs are implemented because, by definition, the construction and operation of nuclear plants are ventures with the potential for deepening long-term relationships, according to Nigeria’s top diplomat.

Brigadier General Nicholas Mike Sango, Zimbabwe’s ambassador to the Russian Federation, told me in an interview just before his final departure from Moscow that several issues could strengthen the relationship. Economic cooperation is an important direction. African diplomats have consistently persuaded Russian companies to use the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) as an opportunity for Russian companies to establish footprints on the continent. This viewpoint has not found favour with them, and it is hoped that it will work in the future.

Despite the government’s lack of pronounced incentives for businesses to set their sights on Africa, Russian businesses generally regard Africa as too risky for investment. He stated that Russia must establish a presence on the continent by exporting its competitive advantages in engineering and technological advancement in order to bridge the gap that is impeding Africa’s industrialization and development.

“Worse, there are too many initiatives by too many quasi-state institutions promoting economic cooperation with Africa, saying the same things in different ways but doing nothing tangible,” he explained during the lengthy pre-departure interview. From July 2015 to August 2022, he represented the Republic of Zimbabwe in the Russian Federation. He previously served as a military adviser in Zimbabwe’s Permanent Mission to the UN and as an international instructor in the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Many former ambassadors have made several similar criticisms. According to former South African Ambassador Mandisi Mpahlwa, Sub-Saharan Africa has understandably been low on post-Soviet Russia’s priority list, given that Russia is not as reliant on Africa’s natural resources as other major economies. The reason for this was that Soviet-African relations, based on the fight to push back the borders of colonialism, did not always translate into trade, investment, and economic ties that would have continued seamlessly with post-Soviet Russia.

“Russia’s goal of elevating its bilateral relationship with Africa cannot be realized without close collaboration with the private sector. Africa and Russia are politically close but geographically separated, and people-to-people ties remain underdeveloped. This translates into a lack of understanding on both sides of what the other has to offer. In both countries, there may be a fear of the unknown, “Mpahlawa stated in an interview after completing his ambassadorial duties in Russia.

Professor Gerrit Olivier from the Department of Political Science, the University of Pretoria in South Africa, noted that there had been unprecedented frequent official working visits to and from, but with little visible impact. Russian by its global status, ought to be active in Africa as Western Europe, the European Union, the United States and China are, it is all but playing a negligible role, and at present, its diplomacy is dominated by a plethora of agreements signed – many of which the outcomes remain hardly discernible in African countries.

Several agreements signed are impressive, but it remains how these will be implemented in practice. That, however, obstacles to the broadening of Russian-Africa relations should be addressed. Be that as it may, the Kremlin has revived its interest in the African continent, and it will be realistic to expect that the spade work it is putting in now will at some stage show more tangible results, he said with optimism.

“Russian influence in Africa, despite efforts towards resuscitation, remains marginal. While prioritizing Africa, Russia has to do more with a result-oriented investment like other players in the continent. The official working visits are mainly moves and symbolic, and have little long-term concrete results,” Professor Olivier, who served as South African Ambassador to the Russian Federation from 1991 to 1996, wrote in an email comment from Pretoria, South Africa.

Russia’s African policy is riddled with flaws. According to reports, more than 90 agreements were signed at the conclusion of the first Russia-Africa summit. Thousands of bilateral agreements are still in the works, and century-old promises and pledges to support sustainable development with African countries are authoritatively renewed. Russia is flashing its geopolitical headlights in all directions on Africa, like a polar deer waking up from its deep slumber.

According to Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, several top-level bilateral meetings, memorandums of understanding, and bilateral agreements have occurred in recent years. In November 2021, a policy document titled the ‘Situation Analytical Report’ presented at the TASS News Agency’s headquarters was harshly critical of Russia’s current African policy.

That policy document was prepared by 25 Russian experts headed by Professor Sergey Karaganov, Honorary Chairman of the Council on Defense and Foreign Policy. While the number of high-level meetings has increased, the proportion of substantive issues and concrete outcomes on the agenda has remained small. It explicitly highlights the inconsistency of approaches in dealing with many critical development issues in Africa. Russia, on the other hand, lacks public outreach policies for Africa. Aside from the lack of a public strategy for the continent, there is a lack of coordination among the various state and non-state institutions that work with Africa.

Associate Professor Ksenia Tabarintseva-Romanova of Ural Federal University’s Department of International Relations recognizes significant existing challenges and possibly difficult conditions in Africa-Russia economic cooperation. The establishment of an African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is the most important modern tool for the economic development of Africa. This is unique in terms of exploring and becoming acquainted with the opportunities for business collaboration it provides.

She maintains, however, that successful implementation necessitates a sufficiently high level of economic development in the participating countries, logistical accessibility, and developed industry with the potential to introduce new technologies. This means that in order for the African Continental Free Trade Area to be effective, it must enlist the provision of long-term investment flows from outside. These funds should be used to build industrial plants and transportation corridors.

Tabarintseva-Romanova previously stated in an interview discussion that Russia already has extensive experience with the African continent, making it possible to make investments as efficiently as possible for both the Russian Federation and African countries. Potential African investors and exporters may also look into business collaboration and partnerships in Russia.

However, Russia must find effective exit strategies, abandon loud diplomatic rhetoric, and take the first steps toward strengthening economic engagement with Africa. It must go beyond the traditional rhetoric of Soviet assistance to Africa. Professor Abdullahi Shehu’s mid-October lecture at the Russian Diplomacy Academy suggested that Russia consider the following.

Professor Shehu proposed that Russia invest directly in Africa’s extractive and manufacturing sectors as a viable alternative and long-term option. As evidenced by the sanctions imposed on Russia by the United States and Europe, Africa holds a promising future for the viability and profitability of Russian manufacturing companies interested in relocating to Africa to take advantage of cheap African labour.

The establishment of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the world’s largest of its kind, provides Africa with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for intra-African trade, thereby empowering Africa’s own capacities and investments. Russia must broaden its view of the investment opportunities presented by this single continental market of 55 African countries with a combined population of over 1.3 billion people.

Professor Abdullahi Shehu also cited Joseph Siegle, the Director of Research for the African Centre for Strategic Studies, to back up his point that “Developing more mutually beneficial Africa relations necessitates changes in both substance and process. Such a shift would necessitate Russia establishing more traditional bilateral engagements with African institutions rather than individuals. These initiatives would prioritize trade, investment, technology transfer, and educational exchanges. Many Africans would welcome such Russian initiatives if they were transparently negotiated and implemented equitably.”

Despite setbacks in recent years, the search for effective project and business financing is still ongoing, according to official reports. “There is a lot of demanding work ahead,” Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said during a meeting of the Ministry’s Collegium. “Perhaps there is a need to pay attention to China’s experience, which provides its enterprises with state guarantees and subsidies, thus ensuring the ability of companies to work on a systematic and long-term basis.”

Previous meetings were a marketplace for fantastic ideas. Business leaders frequently discussed the lack of credit lines and guarantees as barriers, as well as a lack of knowledge of the business environment as a challenge. Lavrov stated in a message sent in mid-June that “In these difficult and critical times, Russia’s foreign policy has prioritized strategic partnership with Africa. Russia is encouraged by Africans’ willingness to expand economic cooperation.”

That is why Lavrov’s earlier suggestion, as early as 2019, of writing a chapter on China’s approach and methods in Africa is arguably important, particularly when discussing the issue of relationship-building in the context of the current global changes of the twenty-first century. Russia could follow China’s lead in financing various infrastructure and construction projects in Africa. Within the context of the emerging multipolar world and growing opposition to Western hegemony and neocolonialism, Russia must consider a broad-based approach to strengthening and sustaining impactful multifaceted relations with Africa.

In stark contrast to key global players such as the United States, China, the European Union, and many others, basic research findings show that Russia’s policies have little impact on African development paradigms. Russia’s policies have frequently ignored Africa’s long-term development concerns. Russia must adopt an action plan, a practical document that outlines concrete, substantive cooperation between summits. Finally, Russians must keep in mind that the African Union Agenda 2063 is Africa’s road map.

World

AfBD, AU Renew Call for Visa-Free Travel to Boost African Economic Growth

By Adedapo Adesanya

The African Development Bank (AfDB) and the African Union have renewed their push for visa-free travel to accelerate Africa’s economic transformation.

The call was reinforced at a High-Level Symposium on Advancing a Visa-Free Africa for Economic Prosperity, where African policymakers, business leaders, and development institutions examined the need for visa-free travel across the continent.

The consensus described the free movement of people as essential to unlocking Africa’s economic transformation under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The symposium was co-convened by AfDB and the African Union Commission on the margins of the 39th African Union Summit of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa.

The participants framed mobility as the missing link in Africa’s integration agenda, arguing that while tariffs are falling under AfCFTA, restrictive visa regimes continue to limit trade in services, investment flows, tourism, and labour mobility.

On his part, Mr Alex Mubiru, Director General for Eastern Africa at the African Development Bank Group, said that visa-free travel, interoperable digital systems, and integrated markets are practical enablers of enterprise, innovation, and regional value chains to translate policy ambitions into economic activity.

“The evidence is clear. The economics support openness. The human story demands it,” he told participants, urging countries to move from incremental reforms to “transformative change.”

Ms Amma A. Twum-Amoah, Commissioner for Health, Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development at the African Union Commission, called for faster implementation of existing continental frameworks.

She described visa openness as a strategic lever for deepening regional markets and enhancing collective responses to economic and humanitarian crises.

Former AU Commission Chairperson, Ms Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, reiterated that free movement is central to the African Union’s long-term development blueprint, Agenda 2063.

“If we accept that we are Africans, then we must be able to move freely across our continent,” she said, urging member states to operationalise initiatives such as the African Passport and the Free Movement of Persons Protocol.

Ghana’s Trade and Industry Minister, Mrs Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare, shared her country’s experience as an early adopter of open visa policies for African travellers, citing increased business travel, tourism, and investor interest as early dividends of greater openness.

The symposium also reviewed findings from the latest Africa Visa Openness Index, which shows that more than half of intra-African travel still requires visas before departure – seen by participants as a significant drag on intra-continental commerce.

Mr Mesfin Bekele, Chief Executive Officer of Ethiopian Airlines, called for full implementation of the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM), saying aviation connectivity and visa liberalisation must advance together to enable seamless travel.

Regional representatives, including Mr Elias Magosi, Executive Secretary of the Southern Africa Development Community, emphasised the importance of building trust through border management and digital information-sharing systems.

Ms Gabby Otchere Darko, Executive Chairman of the Africa Prosperity Network, urged governments to support the “Make Africa Borderless Now” campaign, while tourism campaigner Ras Mubarak called for more ratifications of the AU Free Movement of Persons protocol.

Participants concluded that achieving a visa-free Africa will require aligning migration policies, digital identity systems, and border infrastructure, alongside sustained political commitment.

World

Nigeria Exploring Economic Potential in South America, Particularly Brazil

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this interview, Uche Uzoigwe, Secretary-General of NIDOA-Brazil, discusses the economic potential in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners for the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN). Follow the discussion here:

How would you assess the economic potential in the South American region, particularly Brazil, for the Federal Republic of Nigeria? What investment incentives does Nigeria have for potential corporate partners from Brazil?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, my response to the questions regarding the economic potentials in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners would be as follows:

Brazil, as the largest economy in South America, presents significant opportunities for the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The country’s diverse economy is characterised by key sectors such as agriculture, mining, energy, and technology. Here are some factors to consider:

- Natural Resources: Brazil is rich in natural resources like iron ore, soybeans, and biofuels, which can be beneficial to Nigeria in terms of trade and resource exchange.

- Growing Agricultural Sector: With a well-established agricultural sector, Brazil offers potential collaboration in agri-tech and food security initiatives, which align with Nigeria’s goals for agricultural development.

- Market Size: Brazil boasts a large consumer market with a growing middle class. This represents opportunities for Nigerian businesses looking to export goods and services to new markets.

- Investment in Infrastructure: Brazil has made significant investments in infrastructure, which could create opportunities for Nigerian firms in construction, engineering, and technology sectors.

- Cultural and Economic Ties: There are historical and cultural ties between Nigeria and Brazil, especially considering the African diaspora in Brazil. This can facilitate easier business partnerships and collaborations.

In terms of investment incentives for potential corporate partners from Brazil, Nigeria offers several attractive incentives for Brazilian corporate partners, including:

- Tax Incentives: Various tax holidays and concessions are available under the Nigerian government’s investment promotion laws, particularly in key sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and technology.

- Repatriation of Profits: Brazil-based companies investing in Nigeria can repatriate profits without restrictions, thus enhancing their financial viability.

- Access to the African Market: Investment in Nigeria allows Brazilian companies to access the broader African market, benefiting from Nigeria’s membership in regional trade agreements such as ECOWAS.

- Free Trade Zones: Nigeria has established free trade zones that offer companies the chance to operate with reduced tariffs and fewer regulatory burdens.

- Support for Innovation: The Nigerian government encourages innovation and technology transfer, making it attractive for Brazilian firms in the tech sector to collaborate, particularly in fintech and agriculture technology.

- Collaborative Ventures: Opportunities exist for joint ventures with local firms, leveraging local knowledge and networks to navigate the business landscape effectively.

In conclusion, fostering a collaborative relationship between Nigeria and Brazil can unlock numerous economic opportunities, leading to mutual growth and development in various sectors. We welcome potential Brazilian investors to explore these opportunities and contribute to our shared economic goals.

In terms of this economic cooperation and trade, what would you say are the current practical achievements, with supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, I would highlight the current practical achievements in economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil, alongside the supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA.

Here are some key points:

Current Practical Achievements

- Increased Bilateral Trade: There has been a notable increase in bilateral trade volume between Nigeria and Brazil, particularly in sectors such as agriculture, textiles, and technology. Recent trade agreements and discussions have facilitated smoother trade relations.

- Joint Ventures and Partnerships: Successful joint ventures have been established between Brazilian and Nigerian companies, particularly in agriculture (e.g., collaboration in soybean production and agricultural technology) and energy (renewables, oil, and gas), demonstrating commitment to mutual development.

- Investment in Infrastructure Development: Brazilian construction firms have been involved in key infrastructure projects in Nigeria, contributing to building roads, bridges, and facilities that enhance connectivity and economic activity.

- Cultural and Educational Exchange Programs: Programs facilitating educational exchange and cultural cooperation have led to strengthened ties. Brazilian universities have partnered with Nigerian institutions to promote knowledge transfer in various fields, including science, technology, and arts.

Supporting Strategies

- Strategic Trade Dialogue: NIDOA has initiated regular dialogues between trade ministries of both nations to discuss trade barriers, potential markets, and cooperative opportunities, ensuring both countries are aligned in their economic goals.

- Investment Promotion Initiatives: Targeted initiatives have been established to promote Brazil as an investment destination for Nigerian businesses and vice versa. This includes showcasing success stories at international trade fairs and business forums.

- Capacity Building and Technical Assistance: NIDOA has offered capacity-building programs focused on enhancing Nigeria’s capabilities in agriculture and technology, leveraging Brazil’s expertise and sustainable practices.

- Policy Advocacy: Continuous advocacy for favourable trade policies has been a key focus for NIDOA, working to reduce tariffs and promote economic reforms that facilitate investment and trade flows.

Systemic Engagement

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Engaging the private sector through PPPs has been essential in mobilising resources for development projects. NIDOA has actively facilitated partnerships that leverage both public and private investments.

- Trade Missions and Business Delegations: Organised trade missions to Brazil for Nigerian businesses and vice versa, allowing for direct engagement with potential partners, fostering trust and opening new channels for trade.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: NIDOA implements a rigorous monitoring and evaluation framework to assess the impact of various initiatives and make necessary adjustments to strategies, ensuring effectiveness in achieving economic cooperation goals.

Through these practical achievements, supporting strategies, and systemic engagement, NIDOA continues to play a pivotal role in enhancing economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil. By fostering collaboration and leveraging shared resources, we aim to create a sustainable and mutually beneficial economic environment that promotes growth for both nations.

Do you think the changing geopolitical situation poses a number of challenges to connecting businesses in the region with Nigeria, and how do you overcome them in the activities of NIDOA?

The changing geopolitical situation indeed poses several challenges for connecting businesses in the South American region, particularly Brazil, with Nigeria. These challenges include trade tensions, shifting alliances, currency fluctuations, and varying regulatory environments. Below, I will outline some of the specific challenges and how NIDOA works to overcome them:

Current Challenges

- No Direct Flights: This challenge is obviously explicit. Once direct flights between Brazil and Nigeria become active, and hopefully this year, a much better understanding and engagement will follow suit.

- Trade Restrictions and Tariffs: Increasing trade protectionism in various regions can lead to higher tariffs and trade barriers that hinder the movement of goods between Brazil and Nigeria.

- Currency Volatility: Fluctuations in the value of currencies can complicate trade agreements, pricing strategies, and overall financial planning for businesses operating in both Brazil and Nigeria.

- Different regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements in both countries can create challenges for businesses aiming to navigate these systems efficiently.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Changes in global supply chains due to geopolitical factors may disrupt established networks, impacting businesses relying on imports and exports between the two nations.

Overcoming Challenges through NIDOA.

NIDOA actively engages in discussions with both the Brazilian and Nigerian governments to advocate for favourable trade policies and agreements that reduce tariffs and improve trade conditions. This year in October, NIDOA BRAZIL holds its TRADE FAIR in São Paulo, Brazil.

What are the popular sentiments among the Nigerians in the South American diaspora? As the Secretary-General of the NIDOA, what are your suggestions relating to assimilation and integration, and of course, future perspectives for the Nigerian diaspora?

As the Secretary-General of NIDOA, I recognise the importance of understanding the sentiments among Nigerians in the South American diaspora, particularly in Brazil.

Many Nigerians in the diaspora take pride in their cultural roots, celebrating their heritage through festivals, music, dance, and culinary traditions. This cultural expression fosters a sense of community and belonging.

While many individuals embrace their new environments, they often face challenges related to cultural differences, language barriers, and social integration, which can lead to feelings of isolation.

Many express optimism about opportunities in education, business, and cultural exchange, viewing their presence in South America as a chance to expand their horizons and contribute to economic activities both locally and back in Nigeria.

Sentiments regarding acceptance vary; while some Nigerians experience warmth and hospitality, others encounter prejudice or discrimination, which can impact their overall experience in the host country. NIDOA BRAZIL has encouraged the formation of community organisations that promote networking, cultural exchange, and social events to foster a sense of belonging and support among Nigerians in the diaspora. There are currently two forums with over a thousand Nigerian members.

Cultural Education and Awareness Programs: NIDOA BRAZIL organises cultural education programs that showcase Nigerian heritage to local communities, promoting mutual understanding and appreciation that can facilitate smoother integration.

Language and Skills Training: NIDOA BRAZIL provides language courses and skills training programs to help Nigerians, especially students in tertiary institutions, adapt to their new environment, enhancing communication and employability within the host country.

Engaging in Entrepreneurship: NIDOA BRAZIL supports the entrepreneurial spirit among Nigerians in the diaspora by facilitating access to resources, mentorship, and networks that can help them start businesses and create economic opportunities.

Through its AMBASSADOR’S CUP COMPETITION, NIDOA Brazil has engaged students of tertiary institutions in Brazil to promote business projects and initiatives that can be implemented in Nigeria.

NIDOA BRAZIL also pushes for increased tourism to Brazil since Brazil is set to become a global tourism leader in 2026, with a projected 10 million international visitors, driven by a post-pandemic rebound, enhanced air connectivity, and targeted marketing strategies.

Brazil’s tourism sector is poised for a remarkable milestone in 2026, as the country expects to welcome over 10 million international visitors—surpassing the previous record of 9.3 million in 2025. This expected surge represents an ambitious leap, nearly doubling the country’s foreign-arrival numbers within just four years, a feat driven by a combination of pent-up global demand, strategic air connectivity improvements, and a highly targeted marketing campaign.

World

African Visual Art is Distinguished by Colour Expression, Dynamic Form—Kalalb

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this insightful interview, Natali Kalalb, founder of NAtali KAlalb Art Gallery, discusses her practical experiences of handling Africa’s contemporary arts, her professional journey into the creative industry and entrepreneurship, and also strategies of building cultural partnership as a foundation for Russian-African bilateral relations. Here are the interview excerpts:

Given your experience working with Africa, particularly in promoting contemporary art, how would you assess its impact on Russian-African relations?

Interestingly, my professional journey in Africa began with the work “Afroprima.” It depicted a dark-skinned ballerina, combining African dance and the Russian academic ballet tradition. This painting became a symbol of cultural synthesis—not opposition, but dialogue.

Contemporary African art is rapidly strengthening its place in the world. By 2017, the market was growing so rapidly that Sotheby launched its first separate African auction, bringing together 100 lots from 60 artists from 14 foreign countries, including Algeria, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, and others. That same year during the Autumn season, Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris hosted a major exhibition dedicated to African art. According to Artnet, sales of contemporary African artists reached $40 million by 2021, a 434% increase in just two years. Today, Sotheby holds African auctions twice a year, and in October 2023, they raised $2.8 million.

In Russia, this process manifests itself through cultural dialogue: exhibitions, studios, and educational initiatives create a space of trust and mutual respect, shaping the understanding of contemporary African art at the local level.

Do you think geopolitical changes are affecting your professional work? What prompted you to create an African art studio?

The international context certainly influences cultural processes. However, my decision to work with African themes was not situational. I was drawn to the expressiveness of African visual language—colour, rhythm, and plastic energy. This theme is practically not represented systematically and professionally in the Russian art scene.

The creation of the studio was a step toward establishing a sustainable platform for cultural exchange and artistic dialogue, where the works of African artists are perceived as a full-fledged part of the global cultural process, rather than an exotic one.

To what extent does African art influence Russian perceptions?

Contemporary African art is gradually changing the perception of the continent. While previously viewed superficially or stereotypically, today viewers are confronted with the depth of artistic expression and the intellectual and aesthetic level of contemporary artists.

Portraits are particularly impactful: they allow us to see not just an abstract image of a “continent,” but a concrete personality, character, and inner dignity. Global market growth data and regular auctions create additional trust in African contemporary art and contribute to its perception as a mature and valuable movement.

Does African art reflect lifestyle and fashion? How does it differ from Russian art?

African art, in my opinion, is at its peak in everyday culture—textiles, ornamentation, bodily movement, rhythm. It interacts organically with fashion, music, interior design, and the urban environment. The Russian artistic tradition is historically more academic and philosophical. African visual art is distinguished by greater colour expression and dynamic form. Nevertheless, both cultures are united by a profound symbolic and spiritual component.

What feedback do you receive on social media?

Audience reactions are generally constructive and engaging. Viewers ask questions about cultural codes, symbolism, and the choice of subjects. The digital environment allows for a diversity of opinions, but a conscious interest and a willingness to engage in cultural dialogue are emerging.

What are the key challenges and achievements of recent years?

Key challenges:

- Limited expert base on African contemporary art in Russia;

- Need for systematic educational outreach;

- Overcoming the perception of African art as exclusively decorative or ethnic.

Key achievements:

- Building a sustainable audience;

- Implementing exhibition and studio projects;

- Strengthening professional cultural interaction and trust in African

contemporary art as a serious artistic movement.

What are your future prospects in the context of cultural diplomacy?

Looking forward, I see the development of joint exhibitions, educational programs, and creative residencies. Cultural diplomacy is a long-term process based on respect and professionalism. If an artistic image is capable of uniting different cultural traditions in a single visual space, it becomes a tool for mutual understanding.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn