World

Some Reflections on Russia’s Economic Policy with Africa

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

During the September ceremony to receive foreign ambassadors, Russian leader Vladimir Putin offered spiteful goal-setting policy outlines and some aspects of lofty Russia’s economic policy directions for Africa. Most of these directions considered significant have, over these years, featured prominently in all his previous speeches on Russia’s relations with Africa.

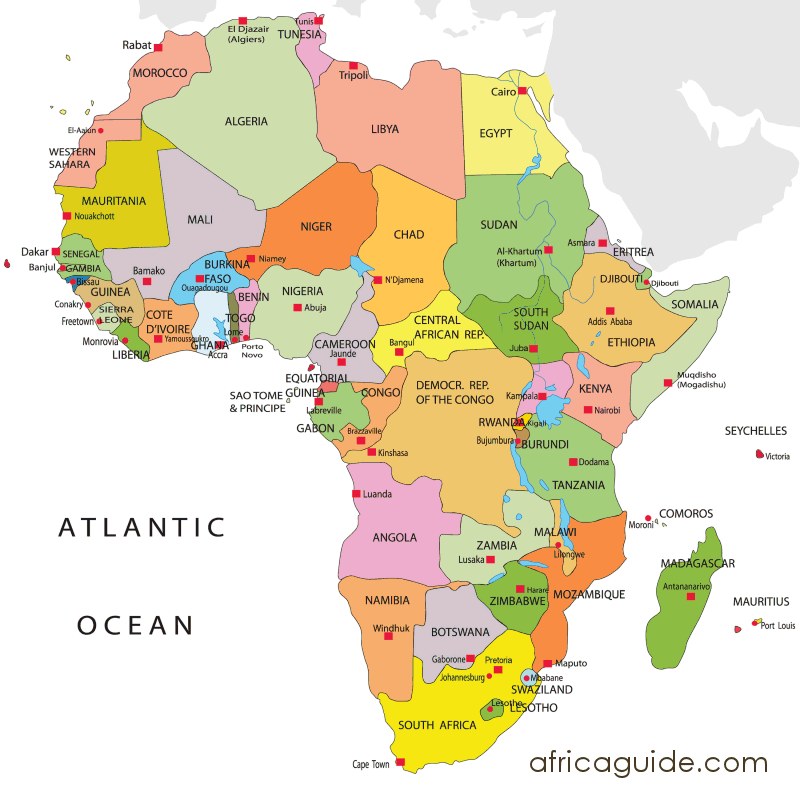

On September 20, in the St Alexander Hall of the Grand Kremlin Palace, Putin received letters of credence from 24 newly-arrived ambassadors, including nine from Africa (Algeria, Egypt, DR Congo, Libya, Mali, Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda). By tradition, Putin briefly characterised the relations between Russia and countries whose envoys came to the Kremlin ceremony.

In a grandiose style, Putin gave a line-up of cheerful-looking ambassadors a step-by-step account of the global situation, the necessity for Russia’s “special military operation” in neighbouring Ukraine, questions relating to regional security, and economic instability due to rising prices for energy and commodities. He underscored the development of multipolar and more democratic and fair world order had entered its active phase.

“Regrettably, the objective movement towards multipolarity has come up against resistance from those trying to preserve their dominant role in international affairs and to control everything – Latin America, Europe, Asia and Africa,” Putin said.

Referencing the current international situation with an emphasis on the critical regional problems of the African continent and the bilateral relations of African countries whose ambassadors were accredited to the Russian Federation, Putin stressed “the importance of the upcoming second Russia-Africa summit in St. Petersburg in 2023 for strengthening diverse relations between Russia and African countries.”

Putin further touched on Moscow’s efforts to restore its geopolitical foothold on the continent after the historical collapse of the Soviet era. While the summit is considered a significant development for Russia’s power-wielding ambitions, Putin strongly reminded African ambassadors that the second Russia-Africa summit is scheduled to be held in St Petersburg in 2023. “We hope that together we will be able to give a new impetus to the comprehensive development of mutually beneficial cooperation between Russia and the African states,” he said.

Significant to note here that at the far end of the first summit, Russia and Africa issued a joint declaration; among the questions was to hold the summit every three years. Both Russia and Africa could not hold the summit during its third year, and both Russia and Africa failed to choose the summit venue. While reasons were not assigned for this sharp inconsistency, policy experts suggested either the Central African Republic (CAR) or the Republic of Mali could hold the summit. CAR and Mali are “reliable Russia’s partners,” and holding the summit would have resonating effects.

During his speech, Putin invited the President of Algeria Abdelmadjid Tebboune, to visit Russia. Understandably, Algeria is Russia’s second-largest trading partner in Africa regarding trade volume. And trade and economic cooperation continue to develop actively, as well as ties in other areas, including military-technical and cultural ties. Reports say Russia supports Algeria’s balanced regional and international affairs policy and continues to work together towards strengthening stability in the Middle East, North Africa and the Sahara-Sahel region.

“We consistently build friendly relations with Egypt under the fundamental Agreement on Comprehensive Partnership and Strategic Cooperation signed in 2018. We view Egypt as one of our most important partners in Africa and the Arab world. We are in constant contact with President Sisi,” according to Putin.

The intergovernmental commission has been working, promoting trade growth, which increased by more than 40 per cent in the first six months of this year. Large joint projects are being implemented, such as constructing the El Dabaa nuclear power plant and creating a Russian industrial zone near the Suez Canal. There is a regular political dialogue and close foreign policy coordination. Within the general policy framework, Russia does not grant concessionary loans and has not publicly allocated a budget for Africa.

But in this exceptional case, Russia and Egypt signed an agreement, and the total cost of construction is fixed at $30 billion. Russia provides Egypt with a loan of $25 billion, which will cover 85% of the work. The Egyptian side will cover the remaining expenses by attracting private investors. Under the agreement, Egypt is to start payments on the loan, which was provided at 3% per annum, in October 2029.

Ambassador Harouna Samake (Republic of Mali) was among the envoys in the Kremlin and listened attentively as Putin welcomed the intention of the leadership of the Republic of Mali to form a long-term strategic partnership with Russia and develop mutually beneficial ties.

During a detailed telephone conversation in August with Interim President Assimi Goïta, Putin agreed to continue joint efforts in countering international terrorism and religious extremism. He further pledged that Russia would continue to provide the Malian people with comprehensive assistance and support in various ways.

The same diplomatic rhetoric praised Russia’s relations with Uganda, one of Russia’s reliable partners in Africa. The United Republic of Tanzania has listed promising spheres such as peaceful nuclear research, transport, energy and tourism. These spheres have been on Russia’s list for many other African countries.

Over the years, Russia has performed dismally in Africa’s transport and energy sector. In theory, it has expressed heightened interest in exploring and producing oil and gas in Africa. But so far, its investment efforts are not seen in the region. Russia claims the leading position as an energy supplier and is now rapidly diversifying its products at discounted prices to the Asian market. Therefore, it is logical that African leaders should not expect much from the Russian Federation in this oil and gas (energy) sector.

Currently, all African countries have a serious energy crisis. Over 620 million in Sub-Saharan Africa do not have electricity out of 1.3 billion people. In this context, several African countries are exploring nuclear energy as part of the solution. Three decades after the Soviet collapse, not a single nuclear plant has been completed in Africa.

Some still advocate for alternative energy supply. Gabby Asare Otchere-Darko, Founder and Executive Director of Danquah Institute, a non-profit organization that promotes policy initiatives and advocates for Africa’s development, wrote in an email that “Africa needs expertise and knowledge transfer that can assist Africa to develop its physical infrastructure, add value to two of its key resources: natural resources and human capital.”

Russia has respectable expertise in one key area for Africa: energy development. “But, has Russia the courage, for instance, to take on the stalled $8-$10 billion Inga-3 hydropower project on the Congo river? This is the kind of development project that can vividly send out a clear signal to African leaders and governments that Russia is, indeed, ready for business,” he said in an interview discussion.

The renewable energy potential is enormous in Africa, citing the Democratic Republic of Congo Grand Inga Dam. Grand Inga is the world’s largest proposed hydropower scheme. It is a grand vision to develop a continent-wide power system. Grand Inga-3 is expected to have an electricity-generating capacity of about 40,000 megawatts – nearly twice as much as the 20 largest nuclear power stations. The cost of building nuclear power does not make sense when compared to the cost of building renewables or other energy sources to solve energy shortages in Africa.

With high optimism and a high desire to strengthen its geopolitical influence, Russia has engaged in sloganism, and many of its signed agreements have not been implemented. The joint declaration adopted at the first summit is intended to raise the African agenda of Russia’s foreign policy to a new level and remains the main document determining the conceptual framework of Russian-African cooperation. Many remain as submit paperwork. China, Japan, India, the United States, the European Union and other players are progressively implementing their African strategies.

Over the years, Russia has shown high interest in Libya, whose ambassador, Emhemed Almaghrawi (State of Libya), was part of the Kremlin ceremony in September. Over the years, Russia has struggled to improve its bilateral political and economic dialogue and cooperation with that North African country. It has faced many pitfalls and obstacles, though.

“We attach great importance to relations with Libya and are interested in a fair and lasting settlement of the protracted internal conflict in that country. Russia will continue to support Libya’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and help the friendly Libyan people defend their right to a decent life, peace and security. As the internal situation in Libya stabilises, we look forward to resuming bilateral cooperation in various fields,” Putin said.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov condemned the Atlantic alliance when he spoke to students at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations in Moscow on September 1. Russia claims it lost billions of dollars in energy, defence, and infrastructure contracts it had negotiated with the removal of Col. Qaddafi. Russia’s state arms exporter lost an estimated $4 billion in Libyan contracts after the UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo on Libya.

Russian Railways had secured a $3 billion contract to build a high-speed rail link from Sirt to Benghazi. Many of these contracts were either signed in Qaddafi’s presence or were organized by him. Russia’s state news agency ITAR-TASS estimates that the country could lose as much as $10 billion in business if Libya’s new leadership challenges the legality of the existing contracts.

As Anna Borshchevskaya, an Ira Weiner Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, observes that military has been part of the foreign policy of the Russian Federation, and Russian authorities have been strengthening military-technical cooperation with some African countries.

“A major driver for Moscow’s push into Africa is military cooperation more broadly. These often include officer training and the sale of military equipment, though the details are rarely publicly available,” she acknowledges, “and it will continue so in Russia’s relations with Africa.

Russia has made significant arms deals with Angola and Algeria. Reports show that Egypt, Uganda, Tanzania, Somalia, Mali, Sudan and Libya have also bought arms from Russia. Small countries such as Burundi, Botswana, and Rwanda, with distinctively impoverished populations and budgetary limitations, have signed agreements. Russia also provides military training and support; it has defence orders worth $14 billion from African countries.

According to Nezavisimaya Gazeta, quoting military experts, Russia has much to gain by promoting and attempting to dispose of its Soviet-era military equipment in Africa. After all, Russia is self-sufficient and has economic independence, so with enthusiasm, convincing African leaders to purchase fertilizers and grains, thereby pushing them towards depleting their hard-earned revenues. Without a doubt, African leaders endlessly boast of vast uncultivated lands.

During these months of the Russia-Ukraine crisis and sanctions from the United States, Europe and Pacific allies, Russian diplomacy has repeatedly stressed that Moscow is ready to export 30 million tons of grain and over 20 million tons of fertilizer by the end of 2022.

According to local Russian media reports, the Russian Agriculture Ministry’s Agroexport Federal Centre for Development of Agribusiness Exports, in close partnership collaboration with Trust Technologies and the business expert community, drew up a business plan for the development of exports for agricultural products (grain, dairy, meat and confectionery products) to promising markets of African countries.

The project’s goal is to prepare a practice-oriented model for increasing supplies and enhancing the competitiveness of Russian agricultural goods in the African market. The report says nine African countries have been chosen as target markets for the delivery of agricultural products. These are Angola, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Nigeria, Tunisia and South Africa.

That report explicitly notes African leaders’ readiness to spend state budgets on food imports; without a doubt, “food security” is the central theme for the 2023 Russia-Africa summit. These countries account for 40% of the continent’s population and one-third of all African imports of agricultural products; Russia estimates to earn some $33 billion from Africa.

In practical terms, a microscopic analysis of Russia’s economic presence gives many interpretations and contradictions. While currently, Russia seems to be soliciting the support of Africa to lead the emerging new world order, Russia still does not recognize that it needs to adopt more public outreach policies to win the minds and hearts of Africans. Its economic footprint on the continent is comparatively weak. Instead of addressing its own investment agenda, it has consistently criticised other foreign players, especially the United States and European countries, that are active in Africa.

Many Russian companies have abandoned their projects in Africa. The latest is the lucrative platinum project contract that was signed for $3 billion in September 2014, the platinum mine is located about 50 km northwest of Harare, the Zimbabwean capital. The Darwendale project involves a consortium of the Rostekhnologii State Corporation, Vneshekonombank and Vi Holding in a joint venture with some private Zimbabwe investors and the Zimbabwean government.

After widely campaigning for the construction of what was referred to as the “Southern Oil&Gas Pipelines” that was supposed to connect three or four southern African countries, Russia’s Rosneft finally abandoned the project. And similarly, State Nuclear Enterprise Rosatom never mentioned again the proposed nuclear plant construction signed by Jacob Zuma of South Africa.

Russia’s Lukoil undertook exploratory feasibility studies in Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Cameroon and Ghana, only to abandon these projects. Nigeria’s Ajeokuta Steel Plant project remains a dream project for Russians. Norilsk Nickel (Nornickel), the Russian mining giant, ceased operations in Botswana. It owned a stake in the Tati Nickel in Botswana, where production was expected to reach its highest level. It has previously given a positive assessment of the possibilities for developing its production assets in South Africa and many African countries. There is a long list of Russian companies that under-performed or performed badly and finally exited Africa.

Just a few weeks before his departure from Moscow, the Zimbabwean ambassador to the Russian Federation, Brigadier General Nicholas Mike Sango, told me in an interview discussion that several issues could strengthen the relationship. One important direction is economic cooperation. African diplomats have consistently been persuading Russia’s businesses to take advantage of the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (ACFTA) as an opportunity for Russian businesses to establish footprints on the continent. This view has not found favour with them, and it is hoped over time, it will.

Although the government has not pronounced incentives for businesses to set sights and venture into Africa, Russian businesses generally view Africa as too risky for their investment. He said that Russia needs to set footprints on the continent by exporting its competitive advantages in engineering and technological advancement to bridge the gap that is retarding Africa’s industrialization and development.

“Worse is that there are too many initiatives by too many quasi-state institutions promoting economic cooperation with Africa saying the same things in different ways, but doing nothing tangible,” he told me during the lengthy pre-departure interview. He served the Republic of Zimbabwe in the Russian Federation from July 2015 to August 2022. He previously held various high-level posts, such as military adviser in Zimbabwe’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations and as an international instructor in the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

There are several similar criticisms from former ambassadors. According to Mandisi Mpahlwa, former South African Ambassador, Sub-Saharan Africa has understandably been low on post-Soviet Russia’s list of priorities, given that Russia is not as dependent on Africa’s natural resources as other major economies. The reason: Soviet and African relations, anchored as they were on the fight to push back the frontiers of colonialism, did not necessarily translate into trade, investment and economic ties, which would have continued seamlessly with post-Soviet Russia.

“Russia’s objective of taking the bilateral relationship with Africa to the next level cannot be realized without a close partnership with the private sector. Africa and Russia are close politically but geographically distant, and the people-to-people ties are still underdeveloped. This translates into a low level of knowledge on both sides of what the other has to offer. There is perhaps also a fear of the unknown in both countries,” Mpahlawa said in an interview after completing his ambassadorial duty in the Russian Federation.

Russia has a lot of policy weaknesses in Africa. Reports indicated that more than 90 agreements were signed at the end of the first Russia-Africa summit. Thousands of bilateral agreements are still on the drawing board, and century-old promises and pledges for supporting sustainable development are authoritatively renewed with African countries. Like a polar deer waking up from its deep slumber, Russia is flashing its geopolitical headlights in all directions on Africa.

Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website indicates that there have been several top-level bilateral meetings, signing of MoUs and bilateral agreements during the past years. In November 2021, a policy document titled the ‘Situation Analytical Report’ presented at the premises of TASS News Agency was very critical of Russia’s current policy towards Africa.

While the number of high-level meetings has increased, the share of substantive issues and definitive results on the agenda remains small. It explicitly points out the inconsistent approach in dealing with Africa. Russia lacks public outreach policies for Africa. Apart from the absence of a public strategy for the continent, there is a lack of coordination among various state and para-state institutions working with Africa.

Ultimately, actions, not words, will determine if upcoming Russia -Africa Summit and the proposed Africa strategy will reset relations with the continent. The significant fact here is that little has been achieved since the first Russia-Africa summit held in October 2019. According to the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Ambassador-at-Large and head of the Secretariat of the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum, Oleg Ozerov, food security will be one of the top issues on the agenda of the second Russia-Africa Summit.

It is a fact that Russia’s ties with Africa declined with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. In the aftermath of the Soviet Union, Russia continues efforts in search of possible collaboration and opportunities for cooperation in the past years. But most essentially, Russians must understand clearly that little has been achieved in Africa. Several bilateral agreements signed with individual countries are not implemented, while in the previous years, there has been an unprecedented huge number of “working visits” to Africa.

According to our research findings, in stark contrast to key global players, for instance, the United States, China, the European Union and many others, Russia’s policies have little impact on African development paradigms. Russia’s policies have often ignored Africa’s sustainable development questions. Experts have repeatedly suggested Russia adopt an Action Plan – a practical document that would fill cooperation with substance between summits. In conclusion, Russians must strongly remember that Africa’s roadmap is the African Union Agenda 2063.

World

Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei Dies After Air Strikes

By Dipo Olowookere

Iranian Supreme Leader, Mr Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has died after coordinated airstrikes carried out by the United States and Israel on Tehran on Saturday morning.

His death was confirmed on Sunday morning by Iranian state media, which also disclosed that his daughter and grandchild were among those killed in the bombardment, which destroyed his compound.

Mr Khamenei was killed during a meeting with top leaders of the Middle East country yesterday, including the Defence Minister Amir Nasirzadeh and Revolutionary Guard commander Mohammad Pakpour, who reportedly died too.

His elimination has sparked mixed reactions, with some Iranians on the streets celebrating his demise, and others condemning the joint air strikes.

The President of the United States, Mr Donald Trump, described the late Iranian leader as “one of the most evil people in history,” expressing satisfaction at the action, which he said was “successful,” as it represented justice for both Iranians and Americans.

Meanwhile, Tehran has vowed to further respond to the attacks after initially firing missiles at six neighbours, including Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE, Bahrain, and Jordan.

Flight operations in the region have been disrupted because of the retaliatory action of Iran over the weekend, though most of the missiles were intercepted.

World

AfBD, AU Renew Call for Visa-Free Travel to Boost African Economic Growth

By Adedapo Adesanya

The African Development Bank (AfDB) and the African Union have renewed their push for visa-free travel to accelerate Africa’s economic transformation.

The call was reinforced at a High-Level Symposium on Advancing a Visa-Free Africa for Economic Prosperity, where African policymakers, business leaders, and development institutions examined the need for visa-free travel across the continent.

The consensus described the free movement of people as essential to unlocking Africa’s economic transformation under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The symposium was co-convened by AfDB and the African Union Commission on the margins of the 39th African Union Summit of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa.

The participants framed mobility as the missing link in Africa’s integration agenda, arguing that while tariffs are falling under AfCFTA, restrictive visa regimes continue to limit trade in services, investment flows, tourism, and labour mobility.

On his part, Mr Alex Mubiru, Director General for Eastern Africa at the African Development Bank Group, said that visa-free travel, interoperable digital systems, and integrated markets are practical enablers of enterprise, innovation, and regional value chains to translate policy ambitions into economic activity.

“The evidence is clear. The economics support openness. The human story demands it,” he told participants, urging countries to move from incremental reforms to “transformative change.”

Ms Amma A. Twum-Amoah, Commissioner for Health, Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development at the African Union Commission, called for faster implementation of existing continental frameworks.

She described visa openness as a strategic lever for deepening regional markets and enhancing collective responses to economic and humanitarian crises.

Former AU Commission Chairperson, Ms Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, reiterated that free movement is central to the African Union’s long-term development blueprint, Agenda 2063.

“If we accept that we are Africans, then we must be able to move freely across our continent,” she said, urging member states to operationalise initiatives such as the African Passport and the Free Movement of Persons Protocol.

Ghana’s Trade and Industry Minister, Mrs Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare, shared her country’s experience as an early adopter of open visa policies for African travellers, citing increased business travel, tourism, and investor interest as early dividends of greater openness.

The symposium also reviewed findings from the latest Africa Visa Openness Index, which shows that more than half of intra-African travel still requires visas before departure – seen by participants as a significant drag on intra-continental commerce.

Mr Mesfin Bekele, Chief Executive Officer of Ethiopian Airlines, called for full implementation of the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM), saying aviation connectivity and visa liberalisation must advance together to enable seamless travel.

Regional representatives, including Mr Elias Magosi, Executive Secretary of the Southern Africa Development Community, emphasised the importance of building trust through border management and digital information-sharing systems.

Ms Gabby Otchere Darko, Executive Chairman of the Africa Prosperity Network, urged governments to support the “Make Africa Borderless Now” campaign, while tourism campaigner Ras Mubarak called for more ratifications of the AU Free Movement of Persons protocol.

Participants concluded that achieving a visa-free Africa will require aligning migration policies, digital identity systems, and border infrastructure, alongside sustained political commitment.

World

Nigeria Exploring Economic Potential in South America, Particularly Brazil

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this interview, Uche Uzoigwe, Secretary-General of NIDOA-Brazil, discusses the economic potential in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners for the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN). Follow the discussion here:

How would you assess the economic potential in the South American region, particularly Brazil, for the Federal Republic of Nigeria? What investment incentives does Nigeria have for potential corporate partners from Brazil?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, my response to the questions regarding the economic potentials in South America, particularly Brazil, and investment incentives for Brazilian corporate partners would be as follows:

Brazil, as the largest economy in South America, presents significant opportunities for the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The country’s diverse economy is characterised by key sectors such as agriculture, mining, energy, and technology. Here are some factors to consider:

- Natural Resources: Brazil is rich in natural resources like iron ore, soybeans, and biofuels, which can be beneficial to Nigeria in terms of trade and resource exchange.

- Growing Agricultural Sector: With a well-established agricultural sector, Brazil offers potential collaboration in agri-tech and food security initiatives, which align with Nigeria’s goals for agricultural development.

- Market Size: Brazil boasts a large consumer market with a growing middle class. This represents opportunities for Nigerian businesses looking to export goods and services to new markets.

- Investment in Infrastructure: Brazil has made significant investments in infrastructure, which could create opportunities for Nigerian firms in construction, engineering, and technology sectors.

- Cultural and Economic Ties: There are historical and cultural ties between Nigeria and Brazil, especially considering the African diaspora in Brazil. This can facilitate easier business partnerships and collaborations.

In terms of investment incentives for potential corporate partners from Brazil, Nigeria offers several attractive incentives for Brazilian corporate partners, including:

- Tax Incentives: Various tax holidays and concessions are available under the Nigerian government’s investment promotion laws, particularly in key sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and technology.

- Repatriation of Profits: Brazil-based companies investing in Nigeria can repatriate profits without restrictions, thus enhancing their financial viability.

- Access to the African Market: Investment in Nigeria allows Brazilian companies to access the broader African market, benefiting from Nigeria’s membership in regional trade agreements such as ECOWAS.

- Free Trade Zones: Nigeria has established free trade zones that offer companies the chance to operate with reduced tariffs and fewer regulatory burdens.

- Support for Innovation: The Nigerian government encourages innovation and technology transfer, making it attractive for Brazilian firms in the tech sector to collaborate, particularly in fintech and agriculture technology.

- Collaborative Ventures: Opportunities exist for joint ventures with local firms, leveraging local knowledge and networks to navigate the business landscape effectively.

In conclusion, fostering a collaborative relationship between Nigeria and Brazil can unlock numerous economic opportunities, leading to mutual growth and development in various sectors. We welcome potential Brazilian investors to explore these opportunities and contribute to our shared economic goals.

In terms of this economic cooperation and trade, what would you say are the current practical achievements, with supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA?

As the Secretary of NIDOA Brazil, I would highlight the current practical achievements in economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil, alongside the supporting strategies and systemic engagement from NIDOA.

Here are some key points:

Current Practical Achievements

- Increased Bilateral Trade: There has been a notable increase in bilateral trade volume between Nigeria and Brazil, particularly in sectors such as agriculture, textiles, and technology. Recent trade agreements and discussions have facilitated smoother trade relations.

- Joint Ventures and Partnerships: Successful joint ventures have been established between Brazilian and Nigerian companies, particularly in agriculture (e.g., collaboration in soybean production and agricultural technology) and energy (renewables, oil, and gas), demonstrating commitment to mutual development.

- Investment in Infrastructure Development: Brazilian construction firms have been involved in key infrastructure projects in Nigeria, contributing to building roads, bridges, and facilities that enhance connectivity and economic activity.

- Cultural and Educational Exchange Programs: Programs facilitating educational exchange and cultural cooperation have led to strengthened ties. Brazilian universities have partnered with Nigerian institutions to promote knowledge transfer in various fields, including science, technology, and arts.

Supporting Strategies

- Strategic Trade Dialogue: NIDOA has initiated regular dialogues between trade ministries of both nations to discuss trade barriers, potential markets, and cooperative opportunities, ensuring both countries are aligned in their economic goals.

- Investment Promotion Initiatives: Targeted initiatives have been established to promote Brazil as an investment destination for Nigerian businesses and vice versa. This includes showcasing success stories at international trade fairs and business forums.

- Capacity Building and Technical Assistance: NIDOA has offered capacity-building programs focused on enhancing Nigeria’s capabilities in agriculture and technology, leveraging Brazil’s expertise and sustainable practices.

- Policy Advocacy: Continuous advocacy for favourable trade policies has been a key focus for NIDOA, working to reduce tariffs and promote economic reforms that facilitate investment and trade flows.

Systemic Engagement

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Engaging the private sector through PPPs has been essential in mobilising resources for development projects. NIDOA has actively facilitated partnerships that leverage both public and private investments.

- Trade Missions and Business Delegations: Organised trade missions to Brazil for Nigerian businesses and vice versa, allowing for direct engagement with potential partners, fostering trust and opening new channels for trade.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: NIDOA implements a rigorous monitoring and evaluation framework to assess the impact of various initiatives and make necessary adjustments to strategies, ensuring effectiveness in achieving economic cooperation goals.

Through these practical achievements, supporting strategies, and systemic engagement, NIDOA continues to play a pivotal role in enhancing economic cooperation and trade between Nigeria and Brazil. By fostering collaboration and leveraging shared resources, we aim to create a sustainable and mutually beneficial economic environment that promotes growth for both nations.

Do you think the changing geopolitical situation poses a number of challenges to connecting businesses in the region with Nigeria, and how do you overcome them in the activities of NIDOA?

The changing geopolitical situation indeed poses several challenges for connecting businesses in the South American region, particularly Brazil, with Nigeria. These challenges include trade tensions, shifting alliances, currency fluctuations, and varying regulatory environments. Below, I will outline some of the specific challenges and how NIDOA works to overcome them:

Current Challenges

- No Direct Flights: This challenge is obviously explicit. Once direct flights between Brazil and Nigeria become active, and hopefully this year, a much better understanding and engagement will follow suit.

- Trade Restrictions and Tariffs: Increasing trade protectionism in various regions can lead to higher tariffs and trade barriers that hinder the movement of goods between Brazil and Nigeria.

- Currency Volatility: Fluctuations in the value of currencies can complicate trade agreements, pricing strategies, and overall financial planning for businesses operating in both Brazil and Nigeria.

- Different regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements in both countries can create challenges for businesses aiming to navigate these systems efficiently.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Changes in global supply chains due to geopolitical factors may disrupt established networks, impacting businesses relying on imports and exports between the two nations.

Overcoming Challenges through NIDOA.

NIDOA actively engages in discussions with both the Brazilian and Nigerian governments to advocate for favourable trade policies and agreements that reduce tariffs and improve trade conditions. This year in October, NIDOA BRAZIL holds its TRADE FAIR in São Paulo, Brazil.

What are the popular sentiments among the Nigerians in the South American diaspora? As the Secretary-General of the NIDOA, what are your suggestions relating to assimilation and integration, and of course, future perspectives for the Nigerian diaspora?

As the Secretary-General of NIDOA, I recognise the importance of understanding the sentiments among Nigerians in the South American diaspora, particularly in Brazil.

Many Nigerians in the diaspora take pride in their cultural roots, celebrating their heritage through festivals, music, dance, and culinary traditions. This cultural expression fosters a sense of community and belonging.

While many individuals embrace their new environments, they often face challenges related to cultural differences, language barriers, and social integration, which can lead to feelings of isolation.

Many express optimism about opportunities in education, business, and cultural exchange, viewing their presence in South America as a chance to expand their horizons and contribute to economic activities both locally and back in Nigeria.

Sentiments regarding acceptance vary; while some Nigerians experience warmth and hospitality, others encounter prejudice or discrimination, which can impact their overall experience in the host country. NIDOA BRAZIL has encouraged the formation of community organisations that promote networking, cultural exchange, and social events to foster a sense of belonging and support among Nigerians in the diaspora. There are currently two forums with over a thousand Nigerian members.

Cultural Education and Awareness Programs: NIDOA BRAZIL organises cultural education programs that showcase Nigerian heritage to local communities, promoting mutual understanding and appreciation that can facilitate smoother integration.

Language and Skills Training: NIDOA BRAZIL provides language courses and skills training programs to help Nigerians, especially students in tertiary institutions, adapt to their new environment, enhancing communication and employability within the host country.

Engaging in Entrepreneurship: NIDOA BRAZIL supports the entrepreneurial spirit among Nigerians in the diaspora by facilitating access to resources, mentorship, and networks that can help them start businesses and create economic opportunities.

Through its AMBASSADOR’S CUP COMPETITION, NIDOA Brazil has engaged students of tertiary institutions in Brazil to promote business projects and initiatives that can be implemented in Nigeria.

NIDOA BRAZIL also pushes for increased tourism to Brazil since Brazil is set to become a global tourism leader in 2026, with a projected 10 million international visitors, driven by a post-pandemic rebound, enhanced air connectivity, and targeted marketing strategies.

Brazil’s tourism sector is poised for a remarkable milestone in 2026, as the country expects to welcome over 10 million international visitors—surpassing the previous record of 9.3 million in 2025. This expected surge represents an ambitious leap, nearly doubling the country’s foreign-arrival numbers within just four years, a feat driven by a combination of pent-up global demand, strategic air connectivity improvements, and a highly targeted marketing campaign.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn