Feature/OPED

Diamond Bank: Battling for Survival Under Uzoma Dozie

By Bamidele Ogunwusi

The last four years have not been years with more of good news for Diamond Bank, one of Nigeria’s wholly indigenous banks that emerged in the banking architecture of the country in December 1990.

Since it started operations in 1991, the bank has challenged the market environment by introducing new products, innovative technology and setting new benchmarks through international standards. At a point, the bank was Nigeria’s fastest growing retail bank.

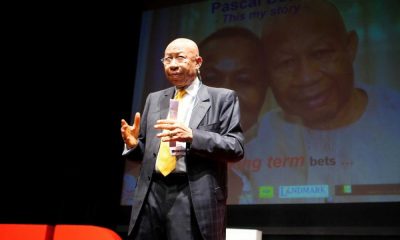

For fourteen years, the bank was under the control of its founder, Mr Pascal Dozie, who was also the Chief Executive Officer of the bank. The fourteen years, according to many stakeholders, were the formative years of the bank and the bank indeed rose to the occasion churning out several innovations.

He relinquished the Chief Executive position to Mr Emeka Onwuka at the end of 2005. His exit would however be heralded with improved performance of the bank, which recorded a profit of N5.445 billion for the year 2005.

Onwuka, who took over effectively from January 2006 and handed it over to Alex Otti in 2011 and later to the son of the founder, Uzoma Dozie in March 2014.

The Otti’s years as Managing Director of the bank was referred to as the golden era and the most productive in the history of the bank.

Diamond Bank in Numbers

The period between 1991 and 2000, the bank tried to make its mark in the murky waters of the banking industry in the country and from 2000 the bank began to see improvements in its performance.

In 2001, the bank reported a loss after tax of N467.819 million while there was an improvement in its performance the following year when it reported a loss after tax of N134.960 million. This greatly improved in 2003 when it posed a profit after tax of N903.411 million.

This steadily grew to N7.086 billion at the end of 2007 financial year. It was N2.508 billion in 2004, N5.44 billion in 2005 and N3.977 billion in 2006.

This leaped to N12.821 billion in 2008, while bad loans brought the operations of the bank on its knees in the subsequent two financial years when profit dropped to N1.328 billion in 2009, a loss of N11.214 billion in 2010, another loss after tax of N13.940 billion in 2011.

There was, however, a resurgence in 2012 when the bank posted a profit after tax of N22.108 billion , the first full year in the Alex Otti’s leadership of the bank.

Under Dr. Otti’s leadership, Diamond Bank made a remarkable return to profitability with impressive growth across all performance indicators year-on-year.

After writing off toxic risk assets, which resulted in the loss of N16 billion in 2011, the lender posted a profit before tax of N28.36 billion in 2012 and N32.5 billion in 2013. The bank also saw its total assets rise from N564.9 billion in February 2011 to N1.18 trillion by December 31, 2012 and N1.52 trillion on December 31, 2013.

He is credited with creating the office of the Chief Risk Officer and designating an Executive Director to head the department. He also spear-headed the expansion of the bank by doubling the full staff count from around 2,000 in 2010 to over 4,000 as at mid-2014, even as he vigorously grew the bank’s footprints from a network of 210 branches in 2011 to over 265 branches three years later. It was also under his watch that the bank established an international subsidiary in the United Kingdom, in addition to expansion in Francophone West Africa (Senegal, Togo, and Ivory Coast).

It is to be noted that the Central Bank only recently classified the bank as one of the eight systematically important banks in Nigeria under his watch.

Since the current MD, Uzoma Dozie took over the leadership of the bank in March 2014; the bank’s fortune has been nose-diving.

Many saw his emergence as desperation on the side of the Dozie’s family to ensure that the leadership of the bank returns to the family.

Pascal Dozie was the Executive Director in charge of Lagos Businesses between 2011 and 2013 until his appointment as Deputy Managing Director in April 2013 and charged with the responsibility of overseeing the Retail Banking Directorate of the Bank.

He has attended various specialist and executive development courses in Nigeria and overseas

Following the resignation of Alex Otti, Uzoma Dozie was unanimously appointed by the Board as the Group Managing Director/Chief Executive Officer of the Bank effective November 1, 2014 while the appointment was approved by the Central Bank of Nigeria in December 2014.

In 2015, the bank’s profit after tax went down from N28.36 billion to N5.656 billion. It went down further to N3.499 billion in 2016 and a loss of N9.011 billion in 2017.

In 2017, noticing that it could no longer continue to cope with losses from its subsidiaries, the bank sold its West African operations in Benin, Togo, Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal to Manzi Finances S.A., a Cote d’Ivoire-based financial services holding company.

The bank said the sale of these operations was to enable it focus its resources exclusively on Nigeria as it is poised to capitalise on the positive macro fundamentals inherent in the Nigerian market.

Commenting on the transaction, Diamond Bank’s CEO Uzoma Dozie said: “After 18 years of building the Diamond Bank franchise in other markets in West Africa, the time has come to fully apply our resources to Nigeria. This, Dozie said aligns with Diamond Bank’s strategic objective: to be the fastest growing and most profitable technology-driven retail banking franchise in Nigeria”.

Aside the sale of these operations, the bank is also on the verge of selling its United Kingdom’s operations.

The lender struck a deal with British industrialist, Sanjeev Gupta, earlier this year, after selling its West African subsidiaries last year.

In May, Diamond Bank posted a 2017 loss, its first time in the red in six years after selling assets to conserve capital and to focus on its home market.

Its half-year 2018 pre-tax profit declined by 69 per cent to N2.92bn, hurting its shares, which further fell by 1.60 per cent on Tuesday.

The bank said it expected loan growth to return; growing five per cent this year after credit declined in the first half by 3.6 per cent.

A Bank in Coma

With the latest S&P Global Ratings downgrade of Diamond Bank, it is evident that the fortunes of the bank, which was once one of Nigeria’s top banks about a decade ago has strangely deteriorated into a bank in a coma.

Diamond Bank was downgraded On Weaker-Than-Expected Asset Quality; Outlook Negative

S&P believes that the bank’s provisioning needs will be higher than it initially expected, which will put pressure on the bank’s capitalisation.

Additionally, its foreign-currency liquidity position also remains vulnerable, due to a large upcoming Eurobond maturity in May 2019.

“As a result, we are lowering our global scale ratings on Diamond Bank to ‘CCC+/C’ from ‘B-/B’ and our Nigeria national scale ratings to ‘ngBB-/ngB’ from ‘ngBBB-/ngA-3’.

The negative outlook reflects pressure on the bank’s capitalization and foreign-currency liquidity,” The foremost rating agency said.

The rating action by S&P considers Diamond Bank to be currently dependent on favorable business, financial, and economic conditions to meet its financial obligations.

It said it believed that the bank will have to set aside higher provisions than they initially expected, following the adoption of International Financial Reporting Standard No. 9 (IFRS 9), which implies weaker asset quality than expected and exerts significant pressure on the bank’s capitalization,” The report said

It went further to say that “Following the bank’s successful disposal of its West African subsidiaries, and imminent disposal of its U.K. subsidiary, it expects it to convert its license into a national banking license. The license conversion would mean a lower minimum capital adequacy ratio (10% versus 15% currently) and lower risk of breach. However, the timing is uncertain, and it considers that there is significant pressure on its capital position. Moreover, four of the bank’s 13 board members have resigned recently, which could create instability if left unresolved in the near term.

“As at Dec. 31, 2017, the bank’s regulatory capital adequacy ratio reached 16.7 per cent. It dropped to 16.3 per cent in Sept. 30, 2018, on the back of IFRS 9 implementation and amortization of tier-2 capital instruments. The initial implementation of IFRS 9 resulted in the bank taking a Nigerian naira (NGN) 2.5 billion (approximately $7 million) deduction from retained earnings at June 30, 2018.”

The agency believes that the bank will have to take higher provisions for IFRS 9, using the N31 billion of regulatory risk reserves that it holds under the local prudential guidelines. Based on peers’ experience and the bank’s weak asset-quality indicators, it estimate the impact will significantly exceed the regulatory risk reserves and estimates that their risk-adjusted capital (RAC) ratio will reach 3.4%-3.9 per cent in the next 12-24 months compared with 5.3 per cent at year-end 2017.

The impact, according to S&P, will be somewhat tempered by the capital gain when the sale of the bank’s U.K. subsidiary is finalized.

“We expect the bank’s credit losses to average 5 per cent over the same period, while nonperforming loans (NPLs; including impaired loans and loans more than 90 days overdue but not impaired) will remain above 35% in the next 12-24 months after reaching 40 per cent at Sept. 30, 2018.

“Overall, we think the bank will display losses in the next 12-24 months. In May 2019, Diamond Bank will have to repay its maturing Eurobond principal of $200 million. The bank plans to use its foreign-currency liquidity and the proceeds from the sale of its U.K. subsidiary for the repayment, among other sources. Any delays or unexpected developments could exert downward pressure on the ratings.

”Following the recent resignation of board members, the bank could face some outflows of deposits, but the granularity of its deposit base and its historically good retail franchise are mitigating factors.

“The negative outlook reflects the pressure on the bank’s capitalization from weaker-than-expected asset-quality indicators and on its foreign-currency liquidity due to a large upcoming maturity in May 2019. We could lower the ratings if provisioning needs proves higher than what we currently expect, leading to a decline in capitalization as measured by our RAC ratio (below 3%) or a breach in the local regulatory requirements.”

Financial experts believe that the declaration by S&P may have further put the bank in a more precarious situation and many are calling on the management to look into the system of the bank and proffer solution.

Cyril Ampka, an Abuja-based financial expert, believes that the dwindling fortune of the bank was not unconnected with the decision of the “owners” of the bank to keep the management of the bank in the family.

“If you look at the time the bank started having this problem you will see that it coincide with the emergence of Mr Uzoma Dozie as the Managing Director of the bank. The decision of the owners of the bank to still keep leadership of the bank within the family is not favourable to the fortune of the bank,” he said.

Though the bank claimed it now controls 40 per cent of the volume of Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) transactions in the banking sector but there are indications that the bank is losing several of its clients in most parts of the South-East and South-South to another Tier 2 bank.

No Merger Talk

Reacting to a report that the bank is in discussion with Access Bank over a possible merger or takeover, Uzoma Uja, Diamond Bank’s Company Secretary, said it was not in discussion with any financial institution at the moment on any form of merger or acquisition.

Uja said that the attention of Diamond Bank had been drawn to the rumour in the media stating that the bank was purportedly in discussion with Access Bank to acquire the bank.

“We wish to state categorically that the bank is not in discussion with any financial institution at the moment on any form of merger or acquisition.

“We trust that the above clarifies the position of the bank with regards to the rumour on the various media platforms,” Uja said.

However, recent analysis by proshare had revealed a concern around the survival of the bank and the need for the CBN to act decisively on its financial stability mandate; given the disposition and realities of its Tier 1 banks, a few that had its own hands full in dealing with legacy challenges apart from new operating environmental issues.

The bank had to content with a CBN levy over a disputed role with regards to MTN Nigeria causing it to issue a notice on CBN Levy on the London Stock Exchange on Sep 07, 2018

Sometime later in September 2018, as the Nigerian Stock Exchange (NSE) issued letters and was set to suspend Skye Bank, Unity Bank and Fortis Microfinance for non-submission of its financials in violation of the post-listing rules. A day before the ultimatum expired, the CBN Governor wrote in to ask the NSE to stay action on these institutions because the CBN was involved in serious discussions for which such an action by the NSE may complicate/jeopardize.

It noted that the withdrawal of license of Skye Bank Plc, and issuing a new one to Polaris Bank, equally left a lot of unanswered questions about the investor protection mandate of the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) and of NSE’s observance of its post listing rules which, at the heart of it, dealt with the investor-market trust and integrity issue.

Consequently, it observed that if in the case of the stress test conducted by CBN, which they found out had three (3) banks failing the minimum regulatory liquidity ratio of 30%, but that the non-disclosure of the names of such banks in a controlled manner presented signaling challenges.

“If in the case of Diamond Bank, with its sheer size and base, has its capital eroded due to huge NPLs with no proactive approach to its resolution plans; and continues to engage in communications juggling, what signals should the markets pick from the state of affairs of such an institution?”

The hole created in the capital gap is quite huge and to fill the hole will require, according to the analysts. Significant haircut from the CBN; Forbearance of accounts (including NPL’s) against the bank; and A fresh injection of capital that could easily come from an ‘acquisition’.

Note: The headline of this story was cast by Business Post but the article was culled from Daily Independent Newspaper

Feature/OPED

If You Understand Nigeria, You Fit Craze

By Prince Charles Dickson PhD

There is a popular Nigerian lingo cum proverb that has graduated from street humour to philosophical thesis: “If dem explain Nigeria give you and you understand am, you fit craze.” It sounds funny. It is funny. But like most Nigerian jokes, it is also dangerously accurate.

Catherine’s story from Kubwa Road is the kind of thing that does not need embellishment. Nigeria already embellishes itself. Picture this: a pedestrian bridge built for pedestrians. A bridge whose sole job description in life is to allow human beings cross a deadly highway without dying. And yet, under this very bridge, pedestrians are crossing the road. Not illegally on their own this time, but with the active assistance of a uniformed Road Safety officer who stops traffic so that people can jaywalk under a bridge built to stop jaywalking.

At that point, sanity resigns.

You expect the officer to enforce the law: “Use the bridge.” Instead, he enforces survival: “Let nobody die today.” And therein lies the Nigerian paradox. The officer is not wicked. In fact, he is humane. He chooses immediate life over abstract order. But his humanity quietly murders the system. His kindness baptises lawlessness. His good intention tells the pedestrian: you are right; the bridge is optional.

Nigeria is full of such tragic kindness.

We build systems and then emotionally sabotage them. We complain about lack of infrastructure, but when infrastructure shows up, we treat it like an optional suggestion. Pedestrian bridges become decorative monuments. Traffic lights become Christmas decorations. Zebra crossings become modern art—beautiful, symbolic, and useless.

Ask the pedestrians why they won’t use the bridge and you’ll hear a sermon:

“It’s too stressful to climb.”

“It’s far from my bus stop.”

“My knee dey pain me.”

“I no get time.”

“Thieves dey up there.”

All valid explanations. None a justification. Because the same person that cannot climb a bridge will sprint across ten lanes of oncoming traffic with Olympic-level agility. Suddenly, arthritis respects urgency.

But Nigeria does not punish inconsistency; it rewards it.

So, the Road Safety officer becomes a moral hostage. Arrest the pedestrians and risk chaos, insults, possible mob action, and a viral video titled “FRSC wickedness.” Or stop cars, save lives, and quietly train people that rules are flexible when enough people ignore them.

Nigeria often chooses the short-term good that destroys the long-term future.

And that is why understanding Nigeria is a psychiatric risk.

This paradox does not stop at Kubwa Road. It is a national operating system.

We live in a country where a polite policeman shocks you. A truthful politician is treated like folklore—“what-God-cannot-do-does-exist.” A nurse or doctor going one year without strike becomes breaking news. Bandits negotiate peace deals with rifles slung over their shoulders, attend dialogue meetings fully armed, and sometimes do TikTok videos of ransoms like content creators.

Criminals have better PR than institutions.

In Nigeria, you bribe to get WAEC “special centre,” bribe to gain university admission, bribe to choose your state of origin for NYSC, and bribe to secure a job. Merit is shy. Connection is confident. Talent waits outside while mediocrity walks in through the back door shaking hands.

You even bribe to eat food at social events. Not metaphorically. Literally. You must “know somebody” to access rice and small chops at a wedding you were invited to. At burial grounds, you need connections to bury your dead with dignity. Even grief has gatekeepers.

We have normalised the absurd so thoroughly that questioning it feels rude.

And yet, the same Nigerians will shout political slogans with full lungs—“Tinubu! Tinubu!!”—without knowing the name of their councillor, councillor’s office, or councillor’s phone number. National politics is theatre; local governance is invisible. We debate presidency like Premier League fans but cannot locate the people controlling our drainage, primary schools, markets, and roads.

We scream about “bad leadership” in Abuja while ignoring the rot at the ward level where leadership is close enough to knock on your door.

Nigeria is a place where laws exist, but enforcement negotiates moods. Where rules are firm until they meet familiarity. Where morality is elastic and context-dependent. Where being honest is admirable but being foolish is unforgivable.

We admire sharpness more than integrity. We celebrate “sense” even when sense means cheating the system. If you obey the rules and suffer, you are naïve. If you break them and succeed, you are smart.

So, the Road Safety officer on Kubwa Road is not an anomaly. He is Nigeria distilled.

Nigeria teaches you to survive first and reform later—except later never comes.

We choose convenience over consistency. Emotion over institution. Today over tomorrow. Life over law, until life itself becomes cheap because law has been weakened.

This is how bridges become irrelevant. This is how systems decay. This is how exceptions swallow rules.

And then we wonder why nothing works.

The painful truth is this: Nigeria is not confusing because it lacks logic. It is confusing because it has too many competing logics. Survival logic. Moral logic. Emotional logic. Opportunistic logic. Religious logic. Tribal logic. Political logic. None fully dominant. All constantly clashing.

So, when someone says, “If dem explain Nigeria give you and you understand am, you fit craze,” what they really mean is this: Nigeria is not designed to be understood; it is designed to be endured.

To truly understand Nigeria is to accept contradictions without resolution. To watch bridges built and ignored. Laws written and suspended. Criminals empowered and victims lectured. To see good people make bad choices for good reasons that produce bad outcomes.

And maybe the real madness is not understanding Nigeria—but understanding it and still hoping it will magically fix itself without deliberate, painful, collective change.

Until then, pedestrians will continue crossing under bridges, officers will keep stopping traffic to save lives, systems will keep eroding gently, and we will keep laughing at our own tragedy—because sometimes, laughter is the only therapy left.

Nigeria no be joke.

But if you no laugh, you go cry—May Nigeria win.

Feature/OPED

Post-Farouk Era: Will Dangote Refinery Maintain Its Momentum?

By Abba Dukawa

“For the marketers, I hope they lose even more. I’m not printing money; I’m also losing money. They want imports to continue, but I don’t think that is right. So I must have a strategy to survive because $20 billion of investment is too big to fail. We are in a situation where we will continue to play cat and mouse, and eventually, someone will give up—either we give up, or they will.” —Aliko Dangote

This statement reflects that while Dangote is incurring losses, he remains committed to his investment, determined to outlast competitors reliant on imports. He believes that persistence and strategy will eventually force them to concede before he does.

Aliko Dangote has faced unprecedented resistance in the petroleum sector, unlike in any of his other business ventures. His first attempt came on May 17, 2007, when the Obasanjo administration sold 51% of Port Harcourt Refinery to Bluestar Oil—a consortium including Dangote Oil, Zenon Oil, and Transcorp—for $561 million. NNPC staff strongly opposed the sale. The refinery was later reclaimed under President Yar’adua, a setback that provided Dangote a tough but invaluable lesson. Undeterred, he went on to build Africa’s largest refinery.

As a private investor, Dangote has delivered much-needed infrastructure to Nigeria’s oil-and-gas sector. Yet, his refinery faces regulatory hurdles from agency’s meant to promote efficiency and growth. Despite this monumental private investment in the nation’s downstream sector, powerful domestic and foreign oil interests may have influenced Farouk Ahmad, former NMDPRA Managing Director, to hinder the refinery’s operations.

The dispute dates back to July 2024, when the NMDPRA claimed that locally refined petroleum products including those from Dangote’s refinery were inferior to imported fuel. Although the confrontation appeared to subside, the underlying rift persisted. Aliko Dangote is not one to speak often, but the pressure he is facing has compelled him to break his silence. He has begun to speak out about what he sees as a deliberate targeting of his investments, as his petroleum-refining venture continues to face repeated regulatory and institutional challenges.

The latest impasse began when Dangote accused the NMDPRA of issuing excessive import licenses for petroleum products, undermining local refining capacity and threatening national energy security. He alleged that the regulator allowed the importation of cheap fuel, including from Russia, which could cripple domestic refineries such as his 650,000‑barrel‑per‑day Lagos plant.

The conflict intensified after Dangote publicly accused Farouk Ahmad, former head of NMDPRA, of living large on a civil servant’s salary. Dangote claimed Ahmad’s lifestyle was way too lavish, pointing out that four of his kids were in pricey Swiss schools. He took his grievance to the ICPC, alleging misconduct and abuse of office.

It’s striking how Nigerian office holders at every level have mastered the art of impunity. Even though Ahmad dismissed the accusations but the standoff prompting Ahmad’s resignation. But the bitter irony these “public servants” tasked with protecting citizens’ interests often face zero consequences for violating policies meant to safeguard the Nation and public interest.

The clash of titans lays bare deeper flaws in Nigeria’s petroleum governance. It shows how institutional weaknesses turn regulatory disputes into personal power plays. In a system with robust norms, such conflicts would be settled via clear rules, independent oversight, and transparent processes not media wars and public accusations.

Even before completion, the refinery’s operating license was denied. Farouk Ahmad claimed Dangote’s petrol was subpar, ordering tests that appeared aimed at public embarrassment. Dangote countered with independent public testing of his diesel, challenging the regulator’s claims.

He also invited Ahmad to verify the tests on-site, but the offer was declined. Moreover, NNPC initially refused to supply crude oil, forcing Dangote to source it from the United States a practice that continues.

President Tinubu later directed the NNPC to resume crude supplies and accept payment in naira, reportedly displeasing the state oil company. In addition to presidential directives, Farouk claimed Dangote was producing petrol beyond the approved quantity and insisted that crude oil be purchased exclusively in U.S. dollars a condition Dangote accepted.

From the public’s point of view, the Refinery is a game-changer for Nigeria, with the potential to end fuel imports and boost the economy. With a capacity of 650,000 barrels per day, it produces around 104 million liters of petroleum products daily, meeting 90% of Nigeria’s domestic demand and allowing exports to other West African countries.

The Dangote Refinery is poised to earn foreign exchange, stabilize fuel prices, and strengthen Nigeria’s energy security. However, the ongoing dispute surrounding the refinery underscores the challenges of aligning national interests with regulatory and institutional frameworks.

The Dangote Refinery’s growing dominance has sparked concerns among stakeholders like NUPENG and PENGASSAN, who fear it could lead to a private monopoly, stifling competition and harming smaller players. This concern stems from the refinery’s rejection of the traditional ₦5 million-per-truck levy on petroleum shipments.

However, Dangote has taken steps to address these concerns, reducing the minimum purchase requirement from 2 million liters to 250,000 liters, opening the market to smaller operators and strengthening distribution networks. The refinery has also purchased 2,000 CNG trucks to maintain operations, emphasizing its commitment to making energy affordable and accessible

Many are watching closely to see if Dangote’s actions are driven by a desire for transparency and fairness in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector or private business interests. Did Dangote genuinely want to fight the corruption going on in the sector?, Will Dangote refinery operate for the common good or seek market dominance? Did Farouk Ahmad act in the public interest or obstruct the refinery for hidden oil interests? Will the Dangote Refinery Maintain Its Momentum in the Post-Farouk Era?The dispute between Dangote and Farouk Ahmad remains shrouded in mystery, with the ICPC investigation likely to uncover the truth

To many, the government faces a delicate balancing act: protecting local refiners while ensuring fair competition. While some argue that Dangote’s success shouldn’t come at the expense of smaller players, others see it episodes like this reveal persistent contradictions: powerful interests, fragile institutions, and blurred lines between regulation and politics.The Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) promised a new era of clarity, efficiency, and accountability, but its implementation has been slow. The PIA’s success hinges on addressing these challenges.

What benefits one party can indeed threaten another. Despite entering the sector with good intentions, Dangote has faced relentless pushback, all eyes are on whether the refinery can sustain its momentum. Analysts and commentators are sharing their perspectives based on available data from relevant institutions. If anyone spreads false information, the truth will eventually come out

Dukawa is a journalist, public‑affairs analyst, and political commentator. He can be reached at [email protected]

Feature/OPED

Dangote, Monopoly Power, and Political Economy of Failure

By Blaise Udunze

Nigeria’s refining crisis is one of the country’s most enduring economic contradictions. Africa’s largest crude oil producer, strategically located on the Atlantic coast and home to over 200 million people, has for decades depended on imported refined petroleum products. This illogicality has drained foreign exchange, weakened the naira, distorted investment incentives, and hollowed out state institutions. Instead of catalysing industrialisation, Nigeria’s oil wealth became a mechanism for capital flight, rent-seeking, and institutional decay.

With the challenges surrounding the refining of crude oil, the establishment of Dangote Refinery signifies an important historic moment. The refinery promises to reduce fuel imports to a bare minimum, sustain foreign exchange growth, ensure there is constant fuel domestically, and strategically position Nigeria as a regional exporter of refined oil products if functioned at full capacity. Dangote Refinery symbolises what private capital, technology, and ambition can achieve in Africa following years of fuel queues, subsidy scandals, and global embarrassment.

Nigerians must have a rethink in the cause of celebration. Nigeria’s refining problem is not simply about capacity; it is about systems. Without addressing the policy failures and institutional weaknesses that made Dangote an exception rather than the rule, the country risks replacing one failure with another, this time cloaked in private-sector success.

For a fact, Nigeria desperately needs the emergence of Dangote refinery, and its success is in the national interest. Hence, this is not an argument against the Dangote Refinery. But history warns that structural failures are not solved by scale alone. Over the year, situations have shown that without competition and strong institutions, concentrated market power, whether public or private, can undermine price stability, energy security, and consumer welfare.

The Long Silence of Refinery Investments

Perhaps the most troubling question in Nigeria’s oil history is why none of the global oil majors like Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Total, or Agip has built a major refinery in Nigeria for over four decades. These companies operated profitably in Nigeria, extracted their crude, and sold refined products back to the country, yet never committed capital to domestic refining.

Over the period, it has been shown that policy incoherence has been the cause, not a matter of technical incapacity, such as price controls, resistant licensing processes, subsidy arrears, frequent regulatory changes, and political interference, which made refining an unattractive investment. Importation, by contrast, offered quick returns, lower political risk, and guaranteed margins, often backed by government subsidies.

Nigeria carelessly designed a system that rather rewarded importers and punished refiners. Dangote did not succeed because the system improved; he succeeded despite it. His refinery exists largely because of the concessions from the government, exceptional financial capacity, political access, and a willingness to absorb risks that institutions should ordinarily mitigate. This raises a deeper concern; when institutions fail, progress becomes dependent on extraordinary individuals rather than predictable systems.

The Tragedy of NNPC Refineries

If private investors stayed away, Nigeria’s state-owned refineries should have filled the gap. Instead, the Port Harcourt, Warri, and Kaduna refineries became monuments to mismanagement. Records have shown that between 2010 and 2025, Nigeria reportedly wasted between $18 billion and $25 billion, over N11 trillion, just for Turn Around Maintenance and rehabilitation. Kaduna Refinery alone is estimated to have consumed over N2.2 trillion in a decade.

Despite these expenditures, output remained negligible. This was not merely a technical failure but a governance one. Contracts were poorly monitored, accountability was absent, and consequences were nonexistent. In functional systems, such outcomes trigger investigations, sanctions, and reforms. In Nigeria, the cycle simply repeated itself, eroding public trust and deepening dependence on imports.

Where Is BUA?

Dangote is not the only Nigerian conglomerate to announce refinery ambitions. In 2020, BUA Group unveiled plans for a 200,000-barrels-per-day refinery. Years later, progress remains unclear, timelines have shifted, and execution appears stalled.

This pattern is revealing. When multiple large investors struggle to translate plans into reality, the issue is not ambition but environment. Refinery projects in Nigeria appear viable only at a massive scale and with extraordinary political leverage. Smaller or mid-sized players are effectively crowded out, not by market forces, but by systemic dysfunction.

Policy Failure and the Singapore Comparison

Nigeria often aspires to emulate Singapore’s refining and petrochemical success. The comparison is instructive. Singapore has no crude oil, yet built one of the world’s most sophisticated refining hubs through consistent policy, investor protection, infrastructure planning, and regulatory certainty.

Nigeria chose a different path: price controls, subsidies, weak contract enforcement, and politically motivated policy reversals. Refineries became tools of patronage rather than productivity. Capital exited, infrastructure decayed, and import dependence deepened. The outcome was predictable.

The Cost of Import Dependence

For years, Nigeria spent billions of dollars annually importing petrol, diesel, and aviation fuel. This placed constant pressure on foreign reserves and the naira. Petrol subsidies alone were estimated at N4-N6 trillion per year, often exceeding national spending on health, education, or infrastructure.

Even after subsidy removal, legacy costs remain: distorted consumption patterns, weakened public finances, and entrenched interests built around importation. These interests did not disappear quietly.

Who Really Benefited from the Subsidy?

Although framed as pro-poor, fuel subsidies disproportionately benefited importers, traders, shipping firms, depot owners, financiers, and politically connected intermediaries. Smuggling across borders meant Nigerians subsidised fuel consumption in neighbouring countries.

Ordinary citizens received marginal relief at the pump but paid far more through inflation, deteriorating infrastructure, and underfunded public services. The subsidy system functioned less as social protection and more as elite redistribution.

The Traders’ Dilemma

Why did major fuel marketers like Oando invest in refineries abroad but not in Nigeria? Again, incentives explain behaviour. Importation offered faster returns, lower capital requirements, and political insulation. Domestic refining demanded long-term investment under unstable rules.

In an irrational system, rational actors optimise accordingly. Importation thrived not because it was efficient, but because policy made it so.

FDI and the Confidence Problem

Sustainable Foreign Direct Investment follows domestic confidence. When local investors, who best understand political and regulatory risks, avoid long-term industrial projects, foreign investors take note. Capital flows to environments with predictable pricing, rule of law, and policy consistency.

Nigeria’s challenge is not attracting speculative capital, but building conditions for patient, productive investment.

Dangote and the Monopoly Question

Dangote Refinery deserves credit. But scale brings power, and power demands oversight. If importers exit and no competing refineries emerge, Dangote could dominate refining, pricing, and supply. Nigeria’s experience with cement, where domestic production rose but prices soared due to limited competition, offers a cautionary tale.

Markets function best with competition. Without it, price manipulation, supply risks, and weakened energy security become real dangers, especially in countries with fragile regulatory institutions.

The Way Forward: Competition, Not Replacement

Nigeria does not need to weaken Dangote; it needs to multiply Dangotes. The goal should be a competitive refining ecosystem, not a replacement of a public monopoly with a private monopoly.

This requires transparent crude allocation, open access to pipelines and storage, fair pricing mechanisms, and strong antitrust enforcement. State refineries must either be professionally concessional or decisively restructured. Stalled projects like BUA’s should be unblocked, and modular refineries should be supported.

The Litmus Test

Nigeria’s refining crisis was decades in the making and cannot be solved by one refinery, however large. Dangote Refinery is a turning point, but only if embedded within systemic reform. Otherwise, Nigeria risks trading one form of dependency for another.

The true test is not whether Nigeria can refine fuel, but whether it can build fair, open, and resilient institutions that serve the public interest. In refining, as in democracy, excessive concentration of power is dangerous. Competition remains the strongest safeguard.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: [email protected]

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism9 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking7 years ago

Banking7 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn