Feature/OPED

A Cultural Journalist’s 15 years of Research on Ijaw Culture and Worship

By Jerome-Mario Utomi

No man, according to Aristotle, chooses anything but what he can do himself. And thus, choice is limited to the realm of things humanly possible. Aristotle further stated that there is no choice among impossibilities. Choice, by its very nature, is free. A necessitated choice is not a choice at all but a great sacrifice, he concluded.

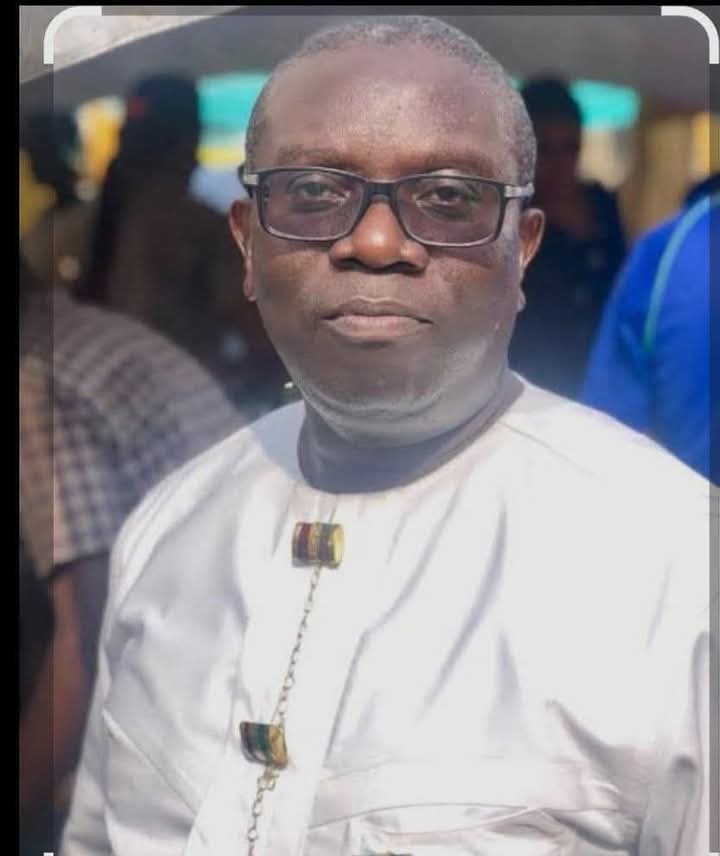

The above lines from great Aristotle amply capture the ‘fate’ or better still the position of Asiayei Enaibo, Bobogbene community, a Warri, Delta state-based journalist who made a necessitated choice/sacrifice by opting out of conventional journalism to explore formation that is supremely foundational to knowledge and cultural production processes. This knowledge in question focuses on the heritage, belief, and values of the true origin and practical belief to commune with the gods and ancestors.

Adding context to the discourse, Asiayei Enaibo hails from Ayakromo, Burutu Local Government Area of Delta State. He is a thoroughbred journalist with great insight into political reportage as well as laced with in-depth knowledge of socioeconomic issues, development and analysis. Also working in his favour is the fact that he is well-foresighted and naturally at home when it comes to broadcast and any other form of commentary.

Despite these virtues, attributes and proficiency needed by the global community, Asiayei Enaibo, in what could be described as extraordinary sacrifice and response to a call for the highest level of spirituality, opt for little-known and less attractive cultural communication where he has since become both sign and symbol to the hearth of traditional worshippers in the whole of Ijaw land and Niger Delta region in general.

Also newsy is the awareness that Asiayei has remained resolute and laced with an unwavering commitment to this spiritual call for the past 15 years, precisely since 2009.

Like a self-willed prisoner, Enaibo has traveled a long windy road to be here.

Most profound about the country is his deep understanding of Ijaw in the African traditional worship institution which has given him both leverage and latitude to deconstruct negative arguments that posture the African traditional worship system as evil. He has not only changed the narrative but vehemently defended African culture and traditional worship system at local and international gatherings.

For instance, he believes and has argued beyond reasonable doubt that the consciousness of Ijaw spirituality hangs on the powers of Egbesu and Egbesu, according to him, is the deity of justice of the Ijaw people of the Niger Delta region. Egbesu, he said is also perceived as the spiritual foundational force for combating evil and cleanses them at every point of confession for forgiveness. The Egbesu force can only be used in defence or to correct an injustice, and only by people who are in harmony with themselves and the universe.

‘Before the coming of the Western religion, Egbesu worship had been in existence. The god of warfare and justice, Egbesu, is regarded as a divine guardian who protects the Ijaw people from their enemies. He is often invoked before battle and is believed to grant victory to those who fight with righteousness and integrity, those who go to the temple of Egbesu must go with a clean heart. If you abore any evil at the point of entrance, there is a pot for purification to cleanse and wipe every evil thought away’.

Enaibo’s investment of his time and talent in cultural journalism has equally seen him widely travelled on a fact-finding mission to the entire Ijaw nation, an ethnic nationality which happens to be the fourth largest in the country.

He has not only made friends and commanded followership but moved severally from Ondo to Edo state, Rivers to Bayelsa down to Akwa Ibom and back to Delta state among others, researching and documenting the undiluted fact that centres on Ijaw history, traditional worships and other critical knowledge areas-as well as participated in high profiled seminars and conferences that has Ijaw culture and traditional worship as its thrust.

This has undeniably made him a reference point for the present and future generations when it comes to Ijaw affairs and in the world of cultural journalism/communication in the Niger Delta region and the nation in general.

However, even as this feat is celebrated, it will on the other hand elicit the questions; first and very importantly, what got Enaibo fixated in this area of communication? Why is cultural communication in the face of other attractive areas of journalism that are considered more lucrative? Why not areas such as political and socioeconomic affairs?

Providing an answer to these questions recently, the Bobogbene/Ayakromo community-born creative writer described himself as a privileged channel chosen by the gods to write their stories, noting that cultural journalism depicts the cultural sensibility of the people and the consciousness of their true identity as their heritage, belief, and values to their true origin and practical belief to commune with the gods of their forefathers.

He said that as a cultural journalist, I feel awakened to the core values of our people. It is the root pride of people who believe in their existence and perception of the God of their creator. I am culturally conscious of the belief practice and worship of the ancestral God of the Ijaw land.

On Ijaw traditional worship, Enaibo has this to say; the great Egbesu is our being that protests the land in time of war, justice, and freedom as an indomitable supernatural power solely for the Ijaws beyond conquest in time of war for justice. Yes, the power manifestation of this spiritual being was deeply abandoned by the coming of the Christian faiths that painted everything in derogatory mental brainwashing. And the gods elude us, but now with Tompolo, there is a new paradigm shift of root consciousness to our Spirituality.

‘Tompolo who I often referred to as gods, begotten son of Ijawland communicates to the gods in the language of metaphysics and gods change its story and that has been with our forefathers. There is no new formation, but what has been. With morality and sincerity, there is no mistake in the story of the gods, and there is no deception, once you hand twist the wish of the land the gods dare you with death or you make an urgent confession and please for forgiveness at the sacred Temple of Egbesu or any other power you have offended’.

‘And it is a few journalists in Ijaw land like myself as part of this entity that the gods reveal their potential to. To me, in any temple I visit, I write their stories with ease because this is an old institution I was born into. Many because of this dislike distance themselves from Cultural Journalism’.

‘From masquerade stories to gods of the land that protect us, to God and man, when we understand the missing bridge, the better prosper us as we have returned to our original paradise lost and regain with full glory as the examples of Tompolo and other high priests of Ijaw land. Writers like Enaibo have an internal soul personality that attracts this energy, purity of thoughts at the same frequency beyond the mundane world,’ he concluded.

Essentially, going by his age and physical appearance, Asiayei in my view, is by no means an old man. But his understanding of and competence in promoting the culture of his people have conspired to confer on him, the enviable title; ‘Talking Drum of Niger region’ by his friends and admirers because of his creative writing prowess. He has proved that history does matter and that ordinary calculation can be upturned by extraordinary personalities.

Enaibo’s regular intervention in Ijaw culture and worship has blown fresh wind to the discourse in ways that accelerate the process of the reemergence of a fully functional historical document that will be trusted by both present and future generations.

Regardless of what others may say, the new awareness created by the cultural journalist can engineer disruptive as well as constructive ideas that will help shatter set patterns of thinking, threaten the status quo or at the very least raise people’s concern to further question time-honoured historical accounts.

A circle of learning and empowerment has been created by Enaibo’s 15 years of unbroken commentary that allows the people of the Ijaw nation to see things that others cannot see.

Another reason why Enaibo’s deep dive into Ijaw cultural journalism should be appreciated is that in population, Ijaws are the fourth largest ethnic nationality in the country. And the people, in material terms, have, through hard work, and planning, established themselves in all sectors-finance, science/technology, sports and education among others.

The above achievements notwithstanding, the people would have needed, yet, another generation to correct some sloppy traditional worship accounts that have invaded so many literary works currently in the public domain if not because of Enaibo’s correctional

Jerome-Mario Chijioke Utomi is the Programme Coordinator (Media and Public Policy) for Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA), Lagos. He can be reached via je*********@***oo.com/08032725374

Feature/OPED

When Expertise Meets Politics: The Rejection of Professor Datonye Dennis by Lawmakers

By Meinyie Okpukpo

In a development that has generated debate within both political and medical circles in Rivers State, the Rivers State House of Assembly recently declined to confirm Professor Datonye Dennis Alasia as a commissioner-nominee submitted by the state governor, Siminalayi Fubara.

The decision followed a tense screening session in Port Harcourt and has raised broader questions about the intersection of politics, governance, and the role of technocrats in public administration.

For many in Nigeria’s medical community, Professor Alasia is not simply a nominee rejected by lawmakers. He is a respected physician, academic, and nephrology specialist whose decades-long career has contributed significantly to medical practice and training in the Niger Delta and across Nigeria.

The Political Drama Behind the Rejection

Professor Alasia was among nine commissioner nominees submitted by Governor Fubara to the Rivers Assembly as part of efforts to reconstitute the State Executive Council following the dissolution of the cabinet earlier in 2026. After deliberations, the Assembly confirmed five nominees but rejected four, including Professor Alasia.

During the screening exercise, lawmakers raised concerns about discrepancies in Alasia’s birth certificate as well as the absence of a tax clearance certificate among the documents he submitted to the Assembly. Although the professor offered explanations and apologised for the missing tax document, a motion was moved on the floor of the House recommending that he should not be confirmed. The Assembly subsequently voted against his nomination. Some lawmakers also cited what they described as “poor performance” during the screening exercise as part of the reasons for their decision. The outcome has since become one of the most talked-about developments from the commissioner screening exercise, largely because of Alasia’s distinguished professional background.

Who Is Professor Datonye Dennis Alasia?

Professor Alasia is widely known in Nigeria’s healthcare sector as a consultant nephrologist and Professor of Medicine with long-standing service at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH). At UPTH, he served as Chairman of the Medical Advisory Committee (CMAC), a key leadership position responsible for overseeing clinical governance, medical standards, and patient-care policies in one of Nigeria’s foremost teaching hospitals.

He also previously held the role of Deputy Chief Medical Director, contributing significantly to hospital administration and the implementation of medical policies within the institution.

In addition to his clinical responsibilities, Professor Alasia has been deeply involved in academic medicine, combining medical practice with teaching and research in the university system.

Advancing Nephrology Care in Nigeria

Professor Alasia specialises in nephrology, the branch of medicine that deals with kidney diseases. This area of medicine is particularly important in Nigeria, where hypertension and diabetes have contributed to a growing number of kidney failure cases.

Through his work as a consultant nephrologist, he has been involved in:

Diagnosis and treatment of kidney diseases

Management of chronic kidney failure

Development of nephrology services in tertiary hospitals

Training doctors in renal medicine

His contributions have helped expand specialised kidney care within the Niger Delta region.

Training the Next Generation of Doctors

Beyond clinical practice, Professor Alasia has also played an important role in medical education.

Teaching hospitals like UPTH serve as the backbone of Nigeria’s medical training system. Within this system, professors supervise:

Residency training programmes

Specialist physician development

Medical student education

Clinical research mentorship

Through these responsibilities, Professor Alasia has helped mentor and train numerous doctors who now practice across Nigeria and beyond.

Leadership in Hospital Administration

Professor Alasia’s role as Chairman of the Medical Advisory Committee at UPTH placed him at the centre of hospital governance.

The position involves responsibilities such as:

Oversight of clinical governance

Enforcement of patient-care standards

Coordination of medical departments

Implementation of healthcare policies

The CMAC position is widely regarded as one of the most influential clinical leadership roles in Nigerian teaching hospitals.

Politics Versus Professional Expertise

The rejection of Professor Alasia highlights a broader issue often seen in Nigerian governance—the tension between professional expertise and political scrutiny. On one hand, the Assembly maintains that its decision reflects its constitutional duty to thoroughly vet nominees and ensure that those appointed to public office meet all necessary requirements. On the other hand, some observers argue that professionals with long careers outside politics may sometimes struggle to navigate political screening processes that are often designed with career politicians in mind.

What Happens Next?

With four nominees rejected during the screening exercise, Governor Fubara may be required to submit new names to the Assembly in order to complete the composition of the State Executive Council.

For Professor Alasia, however, the Assembly’s decision does not diminish a career built over decades in medicine, medical education, and hospital administration.

Conclusion

Professor Datonye Dennis Alasia represents a class of Nigerian professionals whose influence lies primarily outside the political arena. As a professor of medicine, consultant nephrologist, and hospital administrator, his contributions to medical training and kidney disease management remain significant.

Yet his experience before the Rivers State Assembly reflects a recurring reality in Nigerian public life: even the most accomplished technocrats must still navigate the complex and often unforgiving terrain of politics.

Meinyie Okpukpo, a socio-political commentator and analyst, writes from Port Harcourt, Rivers State

Feature/OPED

Compliance is the New Currency of Nigerian Banking

By James Edeh

In the traditional halls of Nigerian finance, capital was once defined solely by the strength of a balance sheet and the depth of physical vaults. However, as the industry transitions into a tech-enabled era, marked by a staggering 11.2 billion electronic transactions processed by NIBSS in 2024 alone, the definition of capital has undergone a fundamental shift.

In 2026, ‘Character’ seems to have emerged as the most vital form of liquidity. In a market where digital fraud and systemic volatility can erode trust overnight, a bank’s commitment to regulatory compliance is no longer a ‘back-office’ function; it is the primary bridge that builds and sustains customer confidence. This evolution is driven by a sophisticated web of regulations from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and the Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (FCCPC), which have moved from reactive policing to proactive architecture. With the introduction of the Digital, Electronic, Online, or Non-traditional Consumer Lending Regulations 2025, the authorities have set a clear mandate: innovation must be tethered to integrity.

The current regulatory landscape is defined by milestones that signal a maturing ecosystem. Nigeria’s successful exit from the FATF ‘grey list’ in October 2025 served as a global validation of the country’s strengthened Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Counter-Terrorism Financing (CFT) frameworks.

The mandatory integration of the Bank Verification Number (BVN) and National Identification Number (NIN) has become the ‘digital DNA’ of banking. This has not only reduced identity fraud, which saw a significant decrease from ₦52.26 billion in 2024 to ₦25.85 billion in 2025, according to the Nigeria Inter-Bank Settlement System NIBSS, but has also provided a secure pathway for 74% of the population to enter the formal financial system. Additionally, the CBN’s 2024–2026 recapitalisation drive, requiring minimum capital thresholds of up to ₦500 billion for international banks, ensures that ‘character’ is backed by the resilience to withstand economic shocks, effectively mandating that only the most robust and compliant players remain at the table.

As of January 2026, the Nigeria’s Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has also significantly increased the minimum capital requirements (MCR) for fintechs and digital asset operators, with compliance required by June 30, 2027. Key thresholds include ₦100 million for Robo-Advisers (up from ₦10m), ₦200 million for Crowdfunding Intermediaries (up from ₦100m), and ₦2 billion for Digital Asset Exchanges (DAX).

At FairMoney MFB, compliance is far more than a regulatory check box, it is the bedrock of our operational integrity and strategic growth. We have engineered a proactive compliance architecture that reaches every level of our organisation, ensuring that we remain with the highest industry standards. By embedding rigorous oversight, ethical governance, and transparent reporting into our core DNA, we have cultivated a foundation of trust that serves as a vital bridge between our organisation and key government stakeholders.

For forward-thinking institutions, compliance is being rebranded as a competitive advantage. In the digital space, where customers cannot visit a branch to demand answers, the ‘seal of approval’ from regulators acts as a proxy for safety.

This is where the concept of Character-as-Capital becomes most visible. By maintaining a strict adherence to responsible debt recovery practices and strictly adhering to the Nigeria Data Protection Act (NDPA), Institutions such as FairMoney MFB demonstrate how compliance-led models can support responsible digital lending. FairMoney’s adherence to the FCCPC’s Digital Lending Guidelines and its proactive stance on product transparency – clearly stating all interest rates and fees upfront – exemplifies how compliance can be used to build a ‘predictability model’ for the consumer. When a bank follows the rules even when it is more expensive to do so, it builds a reservoir of goodwill that serves as a moat against more aggressive, less ethical competitors.

The shift toward a compliance-first culture is yielding a tangible ‘Trust Dividend’. In late 2025, FairMoney’s national scale long-term issuer rating was upgraded from BBB(NG) to BBB+(NG) by Global Credit Rating (GCR), and its short-term rating from A3(NG) to A2(NG). Internal audited records show that in FY2025 FairMoney disbursed over ₦250 billion in loans and paid out over ₦7 billion in interest to savers, proving its ability to return value to a customer base that views the platform as a trusted platform for savings and credit services.

Between 2021 and 2024, FairMoney saw a significant growth in its customer deposit base. This growth has facilitated a reduced cost of funds; because users trust the bank’s CBN and NDIC-licensed status, FairMoney now funds over 56% of its loan book through customer deposits. Recent data from the Nigerian Exchange Limited and banking industry suggests that as compliance improves, so does the velocity of money. Total deposits in the Nigerian banking sector rose by 63% to ₦136 trillion by late 2024, a growth driven by a population that finally feels the digital financial infrastructure is safe enough to hold their life savings.

In the coming years, the winners in the Nigerian banking sector will not be those with the largest marketing budgets, but those with the strongest ethical spine. Compliance is the bridge that connects a sceptical populace to the digital economy. It is the assurance that a customer’s data is private, their deposits are insured, and their treatment is fair. As we look toward 2030, Nigeria’s economic expansion will only be reachable if the banking sector continues to treat Character as its New Capital.

By embracing the rigorous demands of current regulations, financial institutions are not just following the law; they are investing in the most valuable asset any bank can own: the unshakeable confidence of its people. The road ahead requires a commitment to transparency that transcends the app interface and penetrates the core of institutional culture.

James Edeh is the Head of Compliance at FairMoney Microfinance Bank

Feature/OPED

Piracy in Nigeria: Who Really Pays the Price?

Ever noticed how easy it is to get a movie in Nigeria, sometimes before or right after it hits cinemas? For decades, films, music, and series have circulated in ways that felt almost natural; roadside DVDs, download sites, and streaming hacks became part of how we consumed entertainment. It became the default way people experienced content.

But what many don’t realise is that what feels normal for audiences has real consequences for the people behind the screen. As Nigeria’s creative industry grows into a serious economic force, piracy isn’t just a “shortcut” anymore; it’s a drain on the very lifeblood of creativity.

The conversation hit the headlines again with the alleged arrest of the CEO of NetNaija, a platform widely known for downloadable entertainment content. Beyond the courtrooms, the story reopened an important question: how did piracy become so normalised, and why should we care now?

Filmmaker Jade Osiberu put it into perspective in a post that resonated across social media: for many Nigerians, pirated CDs and downloads were simply the most accessible way to watch films. Piracy didn’t just appear from nowhere. It grew because legal options were limited, streaming platforms scarce, and affordability a challenge. In other words, piracy is as much a story about opportunity and access as it is about legality.

The cost of this convenience is real. Every illegally downloaded or shared film chips away at revenue that sustains the people who create it. Producers risk their own capital to tell stories, actors and crew rely on fair compensation, and distributors and cinemas lose income when pirated copies hit screens first. Over time, this doesn’t just hurt profits; it erodes confidence in investing in new projects and threatens the ecosystem that allows Nigerian creativity to flourish.

Piracy is also about culture and necessity. Many audiences never intended harm; they simply wanted stories in a system that didn’t always make legal access easy. Streaming services were limited or expensive, internet access was spotty, and distribution was weak outside major cities. Piracy became the default, and generations grew up seeing it as normal. But what was once a practical workaround has now become a barrier to sustainable growth.

This is where enforcement comes in. Legal action, like the NCC’s intervention against NetNaija, isn’t about pointing fingers at audiences; it’s a reminder that creative work has value and that infringement carries consequences. It’s about sending the message that the people who write, produce, act, and edit these stories deserve protection. Enforcement alone isn’t enough, though. Without accessible, affordable legal alternatives, audiences will naturally gravitate back to piracy.

The bigger picture is this: Nollywood is no longer just a local industry. It’s a global player, employing thousands, creating cultural influence, and generating revenue across multiple sectors. Its growth depends not just on talent, but on a system that rewards creators, protects their work, and builds a sustainable ecosystem.

Piracy may have been normalised in the past, but its consequences today are impossible to ignore. It threatens livelihoods, investment, and the future of stories that define Nigeria culturally and economically. Understanding its impact isn’t about shaming audiences or vilifying platforms; it’s about valuing the people behind the content, the stories themselves, and the industry’s potential.

The real question isn’t just whether piracy is illegal. It’s whether Nigeria is willing to build an entertainment ecosystem where creators thrive, stories get told properly, and audiences can enjoy them without undermining the very people who made them possible. Until that happens, the cost of convenience will keep being paid by someone else, and it’s the people who create the magic.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn