Feature/OPED

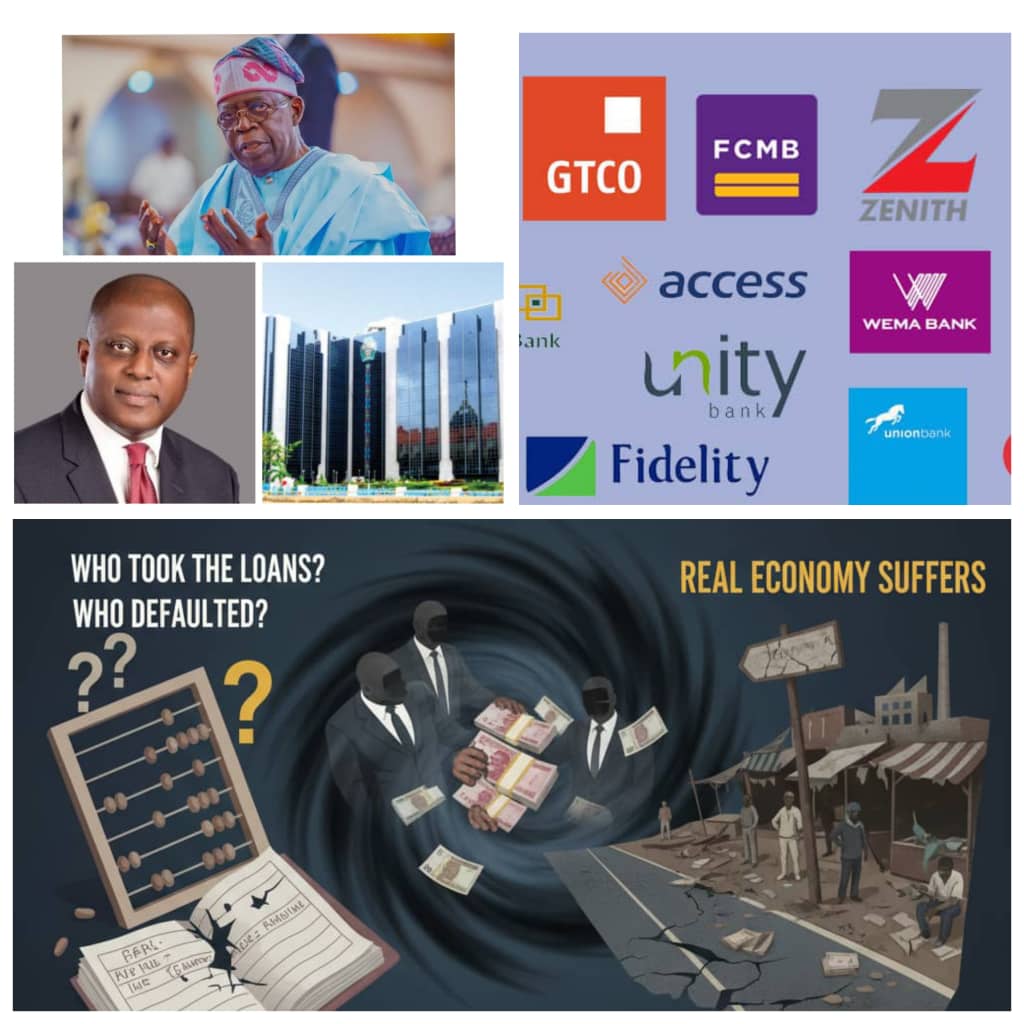

Banks’ N1.96trn Black Hole: Who Took the Loans, Who Defaulted, and Why the Real Economy Suffers

By Blaise Udunze

Nigeria’s banking sector has entered a season of reckoning. Eight of the nation’s biggest banks have collectively booked N1.96 trillion in impairment charges in just the first nine months of 2025 which represents a staggering 49 percent increase from the N1.32 trillion recorded in the same period of 2024.

Behind these figures lies a deeper question that speaks to the very soul of Nigerian finance on who received these loans that have now turned sour? Were they the small and medium enterprises (SMEs), entrepreneurs, and job creators that fuel real economic growth, or were they politically connected insiders and corporate giants whose failures are now being quietly written off at the expense of the public trust?

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is unwinding its pandemic-era forbearance regime, a policy that allowed banks to restructure non-performing loans and delay recognizing potential losses. It was a relief measure meant to protect the economy during the COVID-19 shock. But as the CBN begins to phase out this regulatory cushion, the hidden weaknesses in many banks’ balance sheets are now coming to light.

The apex bank has since placed several lenders under close supervisory engagement, restricting them from paying dividends, issuing executive bonuses, or expanding offshore operations until they meet prudential standards. Those that have satisfied the conditions are being gradually transitioned out ahead of the full forbearance unwind scheduled for March 2026. This shift, though painful, is forcing banks to confront the true state of their loan books and the picture emerging is anything but flattering.

A review of financial statements of Nigeria’s top listed banks reveals the distribution of impairment charges as of the third quarter of 2025.

– Zenith Bank Plc leads the pack with an eye-popping N781.5 billion in impairments, a 63.6 percent jump from N477.8 billion in 2024. Most of this amount to about N711 billion which occurred in the second quarter of 2025, driven by losses on foreign-currency loans and the end of regulatory forbearance. The bank’s gross loans declined by 9 percent to N10 trillion, and though its non-performing loan (NPL) ratio improved to 3 percent, that was largely due to massive write-offs.

– Ecobank Transnational Incorporated (ETI) followed closely, provisioning N393.7 billion, up 47 percent year-on-year. Inflation, exchange-rate volatility, and macroeconomic stress in Nigeria and Ghana all contributed to loan-quality deterioration. Its total loan book stands at N21.1 trillion, with a modestly improved NPL ratio of 5.3 percent.

– Access Holdings Plc posted impairments of N350 billion, representing a 141.5 percent surge year-on-year. About N255 billion of this came from loans to corporate entities and organizations, while the rest were loans to individuals. The bank cited changing macroeconomic conditions, inflationary pressures, and continued regulatory adjustments as the main culprits.

– First HoldCo reported N288.9 billion, up 68.6 percent from N171.4 billion a year earlier. The bank attributed the spike to revaluation losses and write-downs of legacy exposures in the energy and trade sectors. Notably, about N100 billions of this was incurred in the third quarter alone.

– United Bank for Africa (UBA) saw a dramatic improvement, cutting impairments from N123.5 billion to 56.9 billion, thanks to recoveries of N50.4 billion. The bank’s proactive loan-book management and collateral recoveries were credited for this performance.

– Guaranty Trust Holding Company (GTCO) posted N69.8 billion, up slightly from N63.6 billion last year. The group wrote off a key oil-and-gas exposure but maintained strong profitability, with pre-tax return on equity (ROAE) of 39.5 percent.

– Stanbic IBTC Holdings Plc recorded N11.6 billion, a sharp 80 percent decline year-on-year following recoveries of N16.3 billion on previously impaired loans.

– Wema Bank Plc, with N11 billion in impairments, reported one of the lowest provisioning levels in the industry, despite 30 percent loan growth.

Altogether, these eight banks have set aside almost N2trillion in provisions to cover potential losses, a sum roughly equivalent to Nigeria’s entire federal capital expenditure for 2025.

There have been recent claims of a modest level of loan growth that is not commensurate with the overall expansion of the banking system’s balance sheet. Data from MoneyCentral shows that the combined total loans of the nine banks stood at N65.37 trillion as of September 2025, representing a 7.42 percent increase from N60.86 trillion in 2024. This contrasts sharply with a 52.63 percent surge in combined loans recorded in the 2024 financial year and a 32.64 percent increase in 2023, according to data gathered by MoneyCentral.

The underlying question, therefore, is which sectors of the economy are actually benefiting from this reported loan growth?

The real puzzle behind these numbers is who actually received these loans that are now being impaired. While banks have long positioned themselves as engines of private-sector growth, evidence suggests that much of their lending goes to a narrow base of corporate borrowers, politically connected elites, and oil-and-gas companies. These sectors offer large-ticket deals and quick interest earnings but also carry enormous risk.

In contrast, the SME sector, which employs more than 80 percent of Nigeria’s workforce, continues to face credit starvation. Many small businesses are forced to rely on expensive informal loans or personal savings because banks deem them too risky. The pattern is clear that banks chase safety and short-term profits over inclusive growth. When their big corporate bets fail, they write them off through impairment charges, but the cumulative effect is that real economic activity suffers while the credit system grows more fragile.

Another dimension to the problem is the banking industry’s heavy investment in government securities. Over the past two years, Nigerian banks have channeled N20.4 trillion into treasury bills, bonds, and other fixed-income instruments, reaping risk-free returns rather than funding productive ventures. This “securities trap” is profitable for banks but disastrous for the economy. Instead of financing factories, farmers, or tech innovators, banks earn easy money by lending to government thereby crowding out private investment and weakening the transmission of credit to the real sector. When interest rates rise or currency values swing, the market value of these securities falls, forcing banks to record mark-to-market losses that translate into impairment charges. Thus, the same safety net that shields banks from loan risk ends up creating financial volatility of its own.

Beyond macroeconomic challenges, Nigeria’s banks are also grappling with homegrown problems like insider abuses, weak corporate governance, and ineffective risk management. Past crises in the banking sector, from the 2009 consolidation fallout to the 2016 oil-sector shock, reveal a consistent pattern: directors and senior executives often have outsized influence over loan approvals, sometimes extending credit to themselves or politically exposed entities without proper collateral or due diligence. These insider-related loans frequently turn toxic, hidden under layers of restructuring and accounting manoeuvres until a regulatory audit forces exposure.

The recent impairments may well reflect a new cycle of these historical sins as loans extended under pressure, influence, or misplaced optimism, now coming home to roost as the CBN tightens oversight. Corporate-governance codes exist, but enforcement remains uneven. Some banks continue to operate “relationship banking,” were loyalty trumps prudence. The lack of whistleblower protection, combined with weak internal-audit independence, further compounds the problem. Until boards and regulators impose real consequences for reckless lending, the system will continue rewarding the wrong behaviour and punishing taxpayers and shareholders in the long run.

At its heart, impairment is a measure of how well banks anticipate and manage risk. A rise in impairments signals that too many loans were made without properly assessing the borrower’s ability to repay, or that risk models failed to adjust to changing macroeconomic conditions. Several banks blamed their losses on exchange-rate volatility and inflation, but these are hardly new risks in Nigeria’s economic environment. The fact that impairments ballooned even as profits remained high suggests that risk-management frameworks were reactive rather than preventive which focused on compliance rather than foresight. In some cases, the sheer scale of provisioning, such as Zenith’s N781 billion or Access’s N350 billion, points to systemic underestimation of credit risk.

Every naira written off as an impairment represents not just a failed loan but a lost opportunity for the real economy. N1.96 trillion could have funded tens of thousands of new small businesses, millions of jobs, and critical infrastructure projects. Instead, these funds are trapped in the closed circuit of banking losses or vanish into opaque corporate failures. This has broader implications: as banks absorb losses, they tighten lending criteria, making it harder for genuine borrowers to access loans. High impairments signal instability, discouraging foreign investors and depositors, while credit flow dries up, productivity and job creation suffer. The result is a paradoxical economy where banks post impressive profits yet the productive sector languishes.

If there is a silver lining, it is that some banks, notably UBA, Stanbic IBTC, and Wema Bank are demonstrating improved loan-recovery strategies, more disciplined credit models, and a stronger focus on risk-weighted assets. Their experiences prove that impairment is not inevitable; it is the outcome of choices like governance, culture, and accountability. For others, the current round of provisioning should serve as a wake-up call to rethink their business models, diversify exposures, and strengthen compliance culture.

To its credit, the CBN’s forbearance unwind is a critical step toward transparency. By compelling banks to recognize their true loan losses and restricting dividend payouts until they meet prudential standards, the regulator is forcing a long-overdue cleansing of the system. However, reform must go deeper than technical compliance. The CBN must enforce public disclosure of insider-related loans, tighten penalties for concealment, and promote lending to productive sectors through targeted incentives. For instance, a tiered capital framework could reward banks that extend a higher proportion of credit to SMEs and manufacturing, while imposing stricter capital charges on speculative or insider-related lending.

Nigeria’s banking sector has shown resilience through crises, from the global financial meltdown to oil-price collapses. But resilience should not become an excuse for complacency. The N1.96 trillion impairment charges of 2025 are more than a balance-sheet adjustment; they are a mirror reflecting structural flaws in lending culture, governance, and the alignment between finance and development. To rebuild trust and relevance, banks must reorient lending toward real-sector growth, invest in credit analytics and risk intelligence that anticipate shocks, enforce transparency in board-level loan approvals and insider exposures, and collaborate with regulators to design sustainable credit frameworks for SMEs. Above all, there must be a moral recalibration of banking purpose from chasing short-term profits to fueling long-term national prosperity.

The spike in impairment charges does not mean Nigeria’s banks are collapsing. Rather, it signals an industry confronting its hidden fragilities. As the forbearance curtain lifts, the system has a chance to reset to clean up bad debts, rebuild credibility, and reconnect finance with development. But that opportunity will be wasted if the same patterns persist: insider lending, governance lapses, and a preference for easy returns over real investment. Until these issues are confronted head-on, the question will continue to echo through boardrooms and regulatory halls are Nigerian banks truly financing growth or merely recycling risk and protecting privilege? Only transparency, discipline, and a renewed sense of purpose can answer that question in the affirmative.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional writes from Lagos, can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

Feature/OPED

Another Oil Boom: Will Nigeria’s Government Turn Windfall into Growth or Squander it?

By Blaise Udunze

The past recurring conflicts on other continents and the current developments in the Middle East are a clear reminder to the world that energy markets are deeply linked to conflict and uncertainty, as experienced across the globe today. The rise in geopolitical tensions with Iran, Israel, and the United States has led to a sudden increase in global crude oil prices. Some individuals may question what business the war has with Nigeria. Economically, yes, as one of Africa’s major oil producers, Nigeria finds itself in a delicate position amid the current global situation. Since it can gain financially when global crude oil prices skyrocket and this is so because the same increase can create economic challenges locally. The price of Brent crude has jumped to $109.18 per barrel, crossing the $100 mark for the first time in more than five years.

The country is getting a temporary fiscal boost, knowing fully well that prices now surpass the benchmark used in the 2026 national budget. The high oil prices gain is further amplified by two major domestic policy shifts, as the first is the removal of fuel subsidy projected to free nearly $10 billion annually for public investment, and a new Executive Order by President Bola Tinubu aimed at boosting oil and gas revenues flowing into the Federation Account by eliminating wasteful deductions allowed under the Petroleum Industry Act. The combination of these developments could significantly increase government revenue over the next few years, but history shows that such windfalls, if not well managed, often go toward short-term spending rather than creating lasting national wealth.

Moreover, our lingering concern today is that Nigeria as a country has experienced this pattern before, and it often brings instability. One of such examples is the 2022 Ukraine conflict, when oil prices spiked above $100 per barrel.

Obviously, during such a period, countries that export oil will suddenly receive a large and sudden increase in revenue from the sale of crude oil. The truth is that if such a windfall is managed well, it can be used to build stronger and diversify their economies beyond oil. Unfortunately, Nigeria has always told a different story as these opportunities were frequently lost to weak fiscal discipline, rising recurrent expenditure, and limited investment in productive assets. The global conflict, in its real sense, could become an opportunity, even though there are risks inherent. Just like any prudent country, Nigeria can use any short-term benefits (like higher oil revenues) to strengthen its economy for the future.

At the heart of this opportunity lies the need for disciplined fiscal management, if the government will tread in line with this call. It is now time for the policymakers to understand that extra money from oil prices should not be wasted, as it has become a tradition to spend through the regular government expenditures. It is high time the government saved and invested the extra funds it gained wisely rather than spending them all immediately. Nigeria’s fiscal vulnerability has often been exposed whenever oil prices fall or global demand weakens. Establishing strong buffers through sovereign savings mechanisms can protect against such volatility. A significant portion of the windfall should therefore be directed into strengthening the country’s sovereign wealth structures and stabilisation funds. This resonates with our subject matter: Can Nigeria convert Oil Windfall into Economic Strength? This rhetorical question is directed to those at the helm of affairs because, by saving during periods of high prices, Nigeria can build reserves that help sustain public spending during downturns without excessive borrowing.

Closely linked to fiscal buffers is the issue of public debt. Nigeria’s debt servicing obligations have continued to rise in recent years, and the current development might be the answer. The debt has continued to place pressure on government revenues and limit fiscal flexibility. Alarming is the fact that the public debt is projected to have surpassed N177.14 trillion by the end of 2026, which is driven by the budget deficit in the 2026 Appropriation Bill.

The truth is that one sensible response to the current situation would be to use some of the unexpected revenue from higher oil prices to pay off loans (debts), especially those with high interest costs. This would reduce future financial burdens on the government and help it spend on development later. The fact is that debt reduction, if the government can quickly address it, also signals fiscal credibility to investors and international financial institutions, thereby strengthening the country’s macroeconomic reputation.

Beyond fiscal stability, Nigeria must recognise that oil windfalls provide a rare opportunity to accelerate strategic infrastructure investment. In today’s world, infrastructure remains one of the most critical constraints on Nigeria’s economic growth. The cost of doing business in Nigeria has been a serious palaver, and it has continued to discourage and scare investment. This is informed by various structural deficiencies, such as inadequate electricity supply and congested transport corridors, as well as weak logistics networks. The question again, can Nigeria convert Oil Windfall into Economic Strength? This is because the truth is not unknown to leaders, but they have continued to deliberately stay away from the fact that channelling windfall revenues into transformative infrastructure projects can therefore yield long-term economic dividends.

Power sector development should be a top priority. Reliable electricity remains the backbone of industrial productivity and economic expansion. Over the years, a well-known fact is that despite various reforms, Nigeria continues to struggle with an epileptic power supply that forces businesses to rely heavily on expensive diesel generators and has posed a double challenge that comes with noise and atmospheric pollution. The nation is tired of the regular audio investment, but strategic investment in power generation, transmission, and distribution infrastructure would significantly reduce operating costs for businesses that translate into manufacturing and encourage new investment across multiple sectors in the country.

Transportation infrastructure also deserves sustained attention, and if nothing is done, the mass commuters will reap nothing but pain. Nigeria’s highways, rail networks, and ports require large-scale modernisation to support efficient trade and mobility. The unexpected extra income from high oil prices, if used carefully for long-term national benefit, can be used to build transport networks that move food and goods from farms and factories to markets and ports. Businesses today are very much dependent on transportation; hence, improved logistics not only facilitates domestic commerce but also strengthens Nigeria’s position as a regional economic hub in West Africa.

Another critical area for deploying oil windfalls is economic diversification. The over-emphasised dependence of Nigeria on crude oil exports has long exposed the economy to external shocks.

Any rise or fall in global oil prices has an immediate impact on Nigeria’s government revenue since oil exports are a major source of government income, foreign exchange availability, and macroeconomic stability follow suit. To break this cycle, Nigeria must invest aggressively in sectors capable of generating sustainable non-oil income and abstain from the unyielding roundtable discussion of diversification without implementation.

With vast arable land and a large labour force, Nigeria has the capacity to become a global agricultural powerhouse; hence, this is to say that agriculture offers enormous potential in this regard. However, productivity remains constrained by limited mechanisation, inadequate irrigation, and poor storage facilities. If the government intentionally invests in modern agriculture and the systems that support it, the country can produce more food, create jobs via agricultural value chains (from production to processing, storage, transportation, and marketing), while earning more from agricultural exporting.

Manufacturing and industrial development represent another pathway to long-term economic resilience, but this sector has been starved of any tangible investment. Unlike Nigeria, countries that successfully convert natural resource wealth into sustainable prosperity typically invest heavily in industrial capacity. The government should be deliberate in using the extra revenues from the high oil prices to invest in building industrial zones, strengthening hubs, and encouraging the transfer of technologies that will fast-track the production of goods within Nigeria, instead of relying on imports. The unarguable point is that the moment Nigeria invests in industries and production of goods locally instead of buying them from other countries, it becomes better able to manufacture and export products that have higher economic value.

One critical aspect that calls for concern is that strengthening Nigeria’s foreign exchange reserves represents another important avenue for deploying excess oil revenues. The truth, which applies to every economy, is that adequate reserves enhance the country’s ability to stabilise its currency during external shocks and support the operations of the Central Bank of Nigeria in maintaining monetary stability, and this part must not be treated with kid gloves. Given Nigeria’s history of foreign exchange volatility, this is another opportunity to know that building strong reserves can significantly improve investor confidence and macroeconomic resilience.

Human capital development must also remain central to any long-term strategy for managing oil windfalls. A country’s greatest asset is not merely its natural resources but the productivity and innovation of its people, and in Nigeria, more attention has been placed on the former. For so long, Nigeria’s budget allocation has told this story, as the government has been glaringly complacent in investing in quality education, healthcare systems, technical training, and research institutions, which can unlock enormous economic potential. If the government aligns with the necessities, Nigeria’s youthful population represents a demographic advantage that can only be realised through sustained investment in human development.

Investment from the higher oil prices should be channelled to the educational sector, and more emphasis should be placed on science, technology, engineering, and vocational skills that align with the demands of a modern economy. Strengthening universities, technical institutes, and research centres can foster innovation, entrepreneurship, and technological advancement. Similarly, improving healthcare infrastructure enhances workforce productivity and reduces the economic burden of disease. Will the government ever shift reasonable investment to these sectors?

Another strategic use of all the categorised oil windfalls is the expansion of social protection systems that shield vulnerable populations during economic shocks. What is unbeknownst to the government is that while infrastructure and industrial investments drive long-term growth, social protection programs help ensure that economic gains are broadly shared. Helping the poor, creating jobs for young people, and supporting small businesses can make society more stable and grow the economy from the ground up.

Lack of transparency and accountability has been anathema that has hindered the progress of growth in Nigeria. The right implementation will ultimately determine whether Nigeria successfully transforms this oil windfall into lasting prosperity. Public trust in government fiscal management has often been undermined by corruption, waste, and non-transparent financial practices. Once there are clear frameworks for managing windfall revenues, this becomes essential. Also, if it is monitored by neutral institutions that are not controlled by politicians, while information about spending is made available to the populace, the media, and the National Assembly supervises how the funds are spent, it will translate to what benefits the country instead of short-term political interest.

A section of the economy that calls for action is the need to improve the efficiency of government institution capacity within agencies responsible for revenue management, budgeting, and project execution. It is a well-known fact that when government institutions are strong and effective, public money is less likely to be wasted, stolen, or misused, and investments produce measurable economic outcomes. This institutional strengthening should include digital financial systems, procurement transparency, and improved project monitoring mechanisms.

Nigeria’s policymakers must immediately put in place clear fiscal rules governing the use of oil windfalls. This will help define how excess revenues are distributed between savings, infrastructure investment, debt reduction, and social programs, and this will also help Nigeria prevent the politically driven spending patterns that have historically undermined effective resource management.

Another question confronting Nigeria is not whether oil prices will rise again in the future, but whether the country will finally break the cycle of squandered windfalls. It is to the country’s advantage that the current crisis has pushed oil prices above the budget benchmark, creating a temporary revenue advantage, but it must be noted that temporary advantages become transformative only when they are guided by deliberate policy choices and long-term vision.

Nigeria possesses immense economic potential. With a large domestic market, abundant natural resources, and a vibrant entrepreneurial population, the country is well-positioned to achieve sustained growth. This potential requires disciplined management of national wealth, particularly during periods of resource windfalls.

The common saying that a word is enough for the wise is directed to policymakers to understand that, if managed wisely, the current surge in oil revenues could strengthen fiscal buffers, modernise infrastructure, diversify the economy, and invest in human capital. The obvious here is that the investments would not only protect Nigeria against future oil price volatility but also lay the foundation for a more resilient and prosperous economy.

The lesson from global experience, as it has always been, is that resource windfalls do not automatically translate into national prosperity. Nigeria’s leaders must understand that, without exception, countries that succeed are those that convert temporary commodity gains into permanent economic assets. Nigeria now stands at such an intersection, which requires turning crisis-driven oil gains into strategic investments; the nation can transform a moment of geopolitical turbulence into an opportunity for lasting economic resilience and national wealth.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

Feature/OPED

From Presence to Power: Building The Table We Deserve

By Marieme-Sav SOW

Often, I am the only woman in the room – sometimes, the only African woman.

This is not a complaint, but a statement of fact. It is my starting point, and it has offered me an unexpected advantage: being the only one sharpens your awareness. You notice what others overlook.

Early in my career, I believed that dedication and results alone would be enough to transform this industry. But I have since realized that progress demands more than just individual determination -it requires intentional, collective action. Years later, the landscape has shifted: more women attend conferences, more enter junior roles, and more appear in the photos that fill diversity reports. Yet in the rooms where real decisions are made, silence persists. Those spaces remain emptier – and quieter – than they should be. So yes, frankly, I’m weary of watching women’s day celebrations substitute for change.

In my industry, this matters even further because energy is not just about pipelines and power. Energy is about who gets light, who gets jobs, who gets opportunity. When half the population is absent from those decisions, we build systems that serve everyone imperfectly. I witnessed the impact of this firsthand.

In Uganda, a family was being compensated for property affected by a project. The husband spoke; the wife listened. But when asked about the family’s needs, about what “fair compensation” really meant, it was the wife who had the answers. She knew what the household required. She knew who in the community would be affected. She knew because she lived it every day.

That moment changed how I think about influence.

But influence is also about who leads projects, who manages budgets, and who sits on executive committees. In Mozambique, I witnessed a mid-level engineer – a woman – identify a technical flaw that had eluded everyone else. She spoke up, her voice calm yet unmistakably authoritative. The room listened. The plan changed. That, too, is influence. It happens when women are not merely present but empowered to challenge, question, and correct.

At TotalEnergies, I have seen what happens when we design for that kind of influence. In our Tilenga and EACOP projects, compensation requires both spouses’ signatures. Joint bank accounts are mandatory. Financial literacy training reaches both partners. These are small shifts with enormous impact. They work because they recognize that women deserve more than just a place at the table.

In our affiliate in Nigeria, important strides have been made in recent years with intentional diverse hiring practices. As a result, over half of the senior roles filled between 2022 and 2024 went to women. This wasn’t the result of quotas, but of deliberate investment in talent pipelines that made such progress possible, proof that when influence is shared, outcomes improve.

This is what I carry into every boardroom. Not frustration at being the only woman, but a quiet responsibility. To notice what others might not. To ask questions that need to be asked. To ensure that the next generation of African women in this industry has more than a seat. They have influence.

But real influence requires a shared commitment. I urge women: seek out opportunities, develop new skills, and step boldly into leadership. I call on companies: create mentorship, training, and policies that allow women to grow and lead. Together, let us actively enable women to drive innovation and guide the future of energy.

The energy transition underway in Africa is the most profound economic shift of our lifetime. It will determine who prospers and who struggles for generations. We must act now – women must claim their voices and roles in this transition. If we do not, we risk building an energy future as unequal as in the past.

I believe we can do better.

So, I will keep walking into those rooms. I will keep learning from the women I meet along the way. I will give to gain, and I will keep pushing for the kind of deliberate design that turns mere presence into power.

As we mark this month dedicated to the fight for women’s rights everywhere, the goal is not simply more women at the table. The goal is to build the table we deserve.

Marieme-Sav Sow is a Senegalese energy executive, currently VP for Engagement & Advocacy for TotalEnergies EP Africa. A trailblazer, she served as Managing Director in Madagascar and made history as the first woman president of the National Petroleum Association (GPM). A vocal advocate for gender equality and workplace diversity, Marieme-Sav has received numerous recognitions for her leadership, including Africa’s Top 50 Women in Management and the Woman CEO of the Year awards.

Feature/OPED

HerStory in the Making: How Africa Magic is Celebrating Women All March Long

Every year, March arrives with a reminder of just how powerful, resilient, and extraordinary women are. With International Women’s Day anchoring the 8th of March, the entire month has come to be celebrated across the globe as Women’s Month, a time to honour female voices, amplify their stories, and reflect on the journeys that have shaped history.

This year, Africa Magic on GOtv is not just marking the occasion; it’s making a statement. Through a curated lineup of compelling films airing all through March, Africa Magic is dedicating its screens to stories that centre women: their strength, their sacrifices, their secrets, and their survival. The theme? HerStory in the Making.

From tales of mothers fighting to protect their families, to women reclaiming their power after abuse, to fierce rivalries driven by love and jealousy, these are the stories that reflect real life, real womanhood, and real Africa. Here’s a look at what’s showing on Africa Magic this month.

Heartline: Heartline touches on one of love’s oldest truths, that a woman’s presence can quietly dismantle even the most calculated of plans. Heartline follows the journey of a man who arrived with an agenda, a deceptive plot already in motion, and every intention of seeing it through. He didn’t leave the same. What unfolds is something neither he nor you will see coming. There’s just something about the way this story moves that reminds you how effortlessly a woman can change the room, change the plan, and change a man, simply by being herself. Catch Heartline on Saturday, March 7 at 7 pm on Africa Magic Showcase (GOtv Channel 8).

Ashes to Beauty: Ashes to Beauty is the kind of story that hits close to home. It explores the impossible weight mothers carry, the need to be everything, protect everything, and appear as though none of it costs them anything. For this mother, the image was everything: the perfect home, the perfect family, the life she had carefully curated and prayed over. Then a scandal arrives and threatens to burn all of it to the ground. Faced with an impossible decision, she must choose between preserving her image or confronting the truth, no matter the consequences.

This movie is raw and deeply emotional. Watch Ashes to Beauty on Sunday, March 8, at 9 pm on Africa Magic Showcase (GOtv Channel 8).

Love and Friendship: Love and Friendship explores a complicated question many women quietly face: what happens when survival finally gives way to the possibility of love?

After leaving an abusive marriage, Nonye seeks refuge with her closest friend, Somkele, hoping only for peace and a fresh start for herself and her daughter. But when unexpected feelings begin to develop between Nonye and the man Somkele loves, their friendship is suddenly placed in a fragile position. It’s a tender and layered story about loyalty, healing, and the complicated nature of love. Tune in on Saturday, March 7, at 9 pm on Africa Magic Family (GOtv Channel 7).

Emi Nikan: Emi Nikan is a fascinating look at what happens when the structures holding a home together are finally seen for what they are. When circumstances force a proud man to depend on his wife, to step back and let her lead, everything he thought he knew about himself begins to crack. She was always the foundation. He just didn’t know it yet. But as roles reverse and pride gives way, something darker begins to surface beneath the surface of their marriage, a secret that changes everything. This film quietly makes its point: some women have been carrying the weight all along. We just weren’t watching closely enough.

Watch Emi Nikan on Sunday, March 8, at 5:45 pm on Africa Magic Yoruba (GOtv Channel 2).

Thirty and Eligible: Thirty and Eligible is the romantic comedy that feels like it was written about someone you know, maybe even you. Two people in their thirties, both quietly terrified of commitment, stumble into each other and feel something neither was prepared for. So naturally, they both disappear. When the universe pushes them back together, they try to keep it simple, a no-strings arrangement, no feelings, no complications. It works perfectly. Until it doesn’t. Funny, warm, and honest about the very specific chaos of figuring out what you actually want versus what you’ve been telling yourself you want, this one’s for every woman who has ever talked herself out of something wonderful. Watch it on Saturday, March 14 at 7 pm on Africa Magic Showcase (GOtv Channel 8).

With a lineup that cuts across drama, romance, and comedy, March on Africa Magic promises something for every kind of viewer. Whether you’re in the mood for a story that keeps you guessing or one that simply makes you smile, there’s plenty to look forward to on screen this month.

To subscribe, upgrade, or reconnect, download the MyGOtv App or dial *288#. You can also stream anytime with the GOtv Stream App.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn

Pingback: What Nigerian Banks Don’t Want You to Know About Taking a ₦100,000 Loan - FinanceKI