Feature/OPED

Kogi and Bayelsa 2019 Governorship Elections: Foretelling the Outcome

By Omoshola Deji

Democracy is earning the power to govern through free, fair and credible elections. Nigeria is a democratic state, but the leadership recruitment process is largely undemocratic. Material and financial inducements determine victory, the security agencies are political, and the umpire lacks the capacity and will to conduct credible polls. Public sovereignty is departing the ballot for court as the 2019 general elections produced about a thousand petitions.

Subjecting almost every electoral victory to judicial confirmation is making voting lose its essence. Like every human, judges are prone to errors as much as they have preference. Hence, their verdicts can’t always be a true reflection of the peoples will. Several mandates have been mistakenly or deliberately upturned. Parties and candidates must strive to end their contests at the polls, instead of the court.

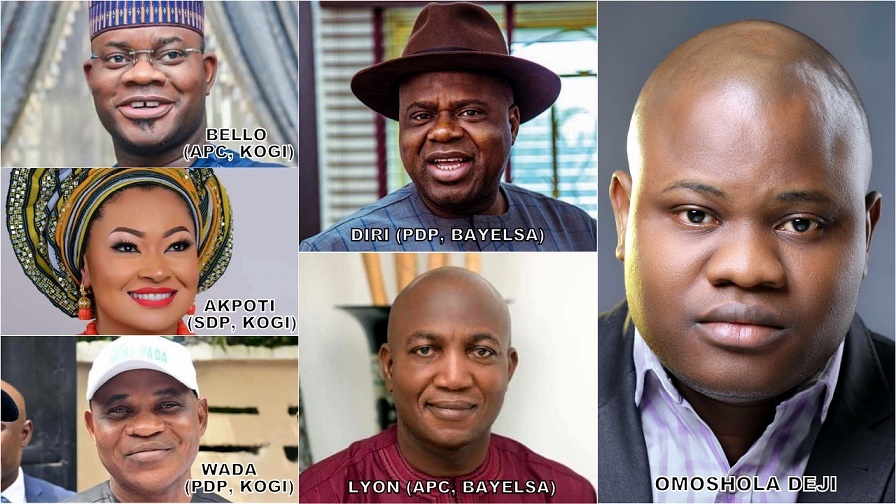

Nigerians hope for this as the people of Kogi and Bayelsa state elect governor on 16 November, 2019. Over 40 parties fielded candidates, but the contest is a two-horse race between the All Progressives Congress (APC) and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). APC’s David Lyon is slugging it out with PDP’s Duoye Diri in Bayelsa state. In Kogi, PDP’s Musa Wada and SDP’s Natasha Akpoti are challenging incumbent Governor Yahaya Bello of the APC. On the sideline, PDP’s Dino Melaye is facing APC’s Smart Adeyemi in the Kogi-West senatorial rerun. This piece foretells the outcome of the elections.

Image Credit: Apply For A Job

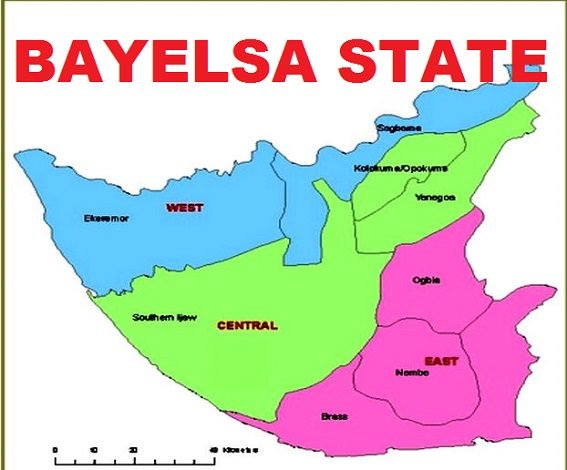

Bayelsa State

Bayelsa is a riverine, less populated state of about 2.5 million persons, eight local governments, and 923,182 registered voters. Unfavorable judicial pronouncements have practically make winning an unattainable height for APC in Bayelsa state. The party’s deputy governorship candidate, Biobarakuma Degi-Eremienyo, was disqualified on November 12 for providing false information in his nomination form. On November 14, the court invalidated David Lyon’s candidacy on account that the governorship primary that produced him was improperly conducted. APC miraculously got a stay of execution at the Court of Appeal few hours after Justice Jane Inyang of Bayelsa High Court gave the ruling.

Is Nigeria’s legal system so flexible that appellants can get a stay of execution the same day judgment is delivered? Did the trial judge err by granting reliefs not sought by Heineken Lokpobiri, the plaintiff who originally prayed to be declared candidate?

In any case, APC is back on the ballot and the poll won’t be a walkover for PDP. The former made an impressive performance in the last general elections and may increase the beat. From scoring a meagre 5,000 votes in the 2015 presidential poll, APC garnered over 118,000 votes in 2019. While one may argue that the party got more votes because a Bayelsa indigene wasn’t on the ballot, as in 2015, the progression is a testament that APC is making waves in Bayelsa.

Ethno-regional balance of power would earn PDP votes. The party’s primary generated resentment, but drastic measures were taken to address the impasse. Diri and the immediate past speaker of the state assembly, Tony Isenah hails from Kolokuma Opokuma. Agitations were rife that the region cannot produce governor and speaker, while Southern Ijaw, the second largest voting population, held no key position. To calm frayed nerves, Governor Seriake Dickson and other PDP leaders forced Isenah out for Monday Obolo. The move has brightened PDP’s chance in Southern Ijaw, the APC candidate’s homeland.

A major setback for the PDP is intra-party crisis. Governor Dickson backed Duoye Diri, against the wish of ex-president Goodluck Jonathan and other bigwigs. Diri’s candidature was actualized through the Restoration Group, the dominant PDP faction in the state controlled by Dickson. Diri pulled 561 votes, while Jonathan’s preferred candidate, Timi Alaibe, scored 365 votes in the primary. Efforts to make Dickson concede the deputy governorship ticket to Alaibe’s faction failed. This made several PDP stalwarts decamp to APC and other parties. Gabriel Jonah, the incumbent deputy governor’s younger brother led the Otita Force group out of the PDP to APC. Some of the defectors have returned and PDP also won some APC decampees.

Recurring conflict of interest broke the cordial relationship between Dickson and his godfather, Jonathan. The latter wants to keep calling the shot, but the former feels he has come of age. Dickson is having his way as the party structure is firmly under his control. Many allege the Jonathans are working against PDP’s victory. Ex-first lady Patience reportedly attend an APC rally and the husband visited President Buhari within the same period. Politics is an interest driven game; hence, it is not impossible, but most unlikely that Jonathan would support APC. This is premised on the manner the party has disparaged him since he lost power in 2015.

Every governor wants to install a successor and Dickson is no exemption. He is striving to enthrone Diri to protect himself from probe and prosecution. Bayelsa’s development is incommensurable with the federal allocation and internal revenue Dickson has accrued. His government spent mammoth funds on less impactful schemes. For instance, the Bayelsa International Cargo Airport was constructed at a prodigious rate, while the population is lacking basic amenities.

Ex-governor Timipre Sylva’s appointment as Minister of State for Petroleum has energized APC in Bayelsa. Sylva hopes to raise his political clout by capturing the state. Poised to bring honey out of the rock, Sylva will use federal might and fund for APC, but the party will not sail through. The 2019 Ameachi-Rivers scenario would most-likely occur. Sylva would predictably incapacitate PDP bigwigs, flood the state with armed officers, and do all legally and illegally possible to enthrone APC. Yet the party would lose. PDP is more formidable despite the intra-party crisis and shortcomings of the Dickson administration. Duoye Diri (PDP) would win the election.

Image Credit: ResearchGate

Kogi State

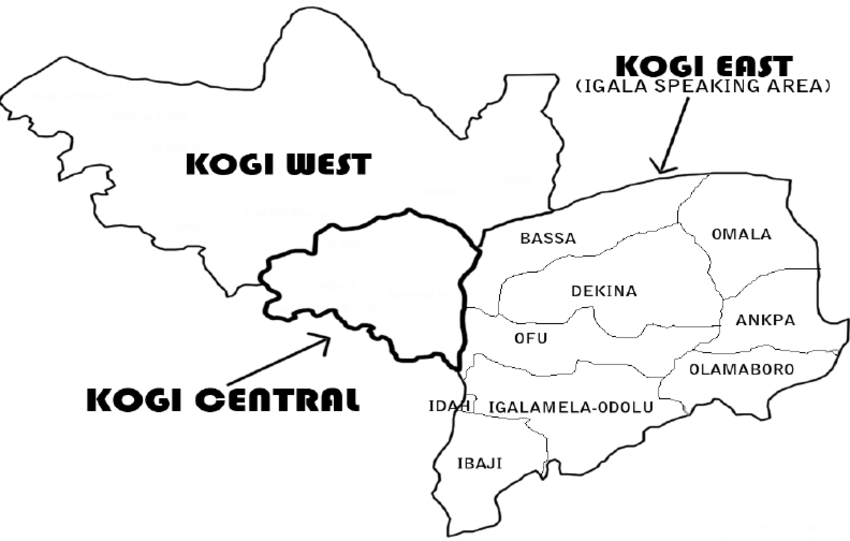

‘Your Excellency’ is a title Nigerian elites admire, and do all possible to acquire. Struggle for the coveted position of governor has made Kogi the violence capital of Nigeria lately. The 2019 governorship poll will go down in history as the fiercest in the state. Yahaya Bello (APC) and Musa Wada (PDP) are not aiming for second and Natasha Akpoti (SDP) is waxing strong. They are campaigning aggressively, spewing unfulfillable promises, and going all out to win the heart of the 1,646,350 registered voters.

Kogi APC had a good outing in the 2019 general election. The party won two of the state’s three senatorial seats, and seven out of the nine House of Representative seats. While this is a pointer that APC is on course for victory, it may lose the governorship election for fielding an unpopular candidate. Bello’s track record shows he’s not deserving of governorship or any other position. He is bereft of ideas, non-tolerant, arrogant, and violent. His address during campaigns are basically hate speeches and threats, rather than a presentation of his scorecard and manifesto.

Another minus for Bello is his style of governance. He ruled Kogi like a conquered territory. His mindset is too shallow to accommodate opposite views and criticisms. You either agree with him or be hounded. He has, at different times, been embroiled in conflict with the labor union, university staffs, and the state’s Chief Judge. Bello also has issues with his former deputy, Elder Simon Achuba. He withheld Achuba’s allowances and honoraria, and influenced his unconstitutional removal from office.

A major impediment to Bello’s re-election is the non-payment of salaries in the civil service, salary-dependent state. Bello has no tenable excuse for owing as he accrued over N300 billion internally generated revenue and federal allocation within 38 months of his administration. Yet workers were unpaid and no landmark project has been commissioned. The state is enmeshed in poverty, unemployment, insecurity and underdevelopment.

Sadly, the funds that should have been used to better Kogites lot would be apparently used for vote-buying. Federal government has aided the practice by releasing N10 billion project-executed repayment fund to Bello three days to the election. It’s upsetting Buhari’s anti-corruption centered government released the fund at a time it would most certainly be used for election purposes.

Vote-buying shouldn’t be aiding poor performing politicians to victory, but most Nigerians are descendants of Esau, the biblical character who sold his birthright for a plate of porridge. Pecuniary gain makes many praise-sing and reelect failed governments. Kogi people won’t act different. Many would vote the poor performing governor after receiving peanuts. Vote-buying is not a one-party affair. PDP also induce voters and will do so again in Kogi.

Ethnic politics reigns supreme in Kogi. The population often deliver bulk votes to their tribesmen, irrespective of party. Igala tribe has numerical advantage and principally determines who carry the day. In 1999, Abubakar Audu won the governorship election under the defunct All Nigeria Peoples Party, defeating PDP which had better structures at the time. Igala people are domiciled in Kogi East and constitutes over half of the state’s voting population. PDP’s Wada and the APC deputy governorship candidate, Edwin Onoja are Igala natives.

If ethnic voting occurs, Wada would win as Bello hails from the less populated Ebira tribe. Onoja’s influence won’t earn APC majority vote; Igala people would rather be first than play second fiddle. Moreover, Wada’s allies are conversant with the tactics of winning elections in Kogi state, especially Igala land. The PDP candidate is the brother of ex-governor Idris Wada and in-law of ex-governor Ibrahim Idris.

Bello is hoping to harvest Ebira votes in Kogi Central, but Akpoti is a pain. The budding politician’s fan base is increasing outstandingly. Her supporters are largely women, a crucial and influential arm of the voting population. Akpoti knows she can’t win, but wants to split Bello’s vote in Kogi Central, not minding who her action benefits. Having her way would propel PDP to victory and Bello’s army of thugs won’t watch that happen. They allegedly set her campaign office ablaze and have been harassing her routinely. This misstep is earning Akpoti the popularity she might have joined the race for. It would also earn her sympathy votes, which may be inadequate to make her win, but sufficient to make Bello lose. In case Bello gets injured in Kogi Central (which is most unlikely), he will hope on recovering at Kogi West.

Kogi West Senatorial Rerun

One man’s misfortune is often another’s stroke of luck. Dino Melaye’s trouble turned to blessing for Wada when he needs it most. The former’s senatorial mandate was nullified and rerun is holding alongside the governorship election. Melaye who had initially distanced himself from Wada’s campaign, having lost out in the primary, backtracked upon realizing him and Wada must either rise or fall together.

Melaye is facing arch-rival Smart Adeyemi of the APC in an epic rerun. In the nullified February 2019 election, Melaye defeated Adeyemi in six out of the seven local governments constituting Kogi West. He won despite being hounded by the state and federal government, and under a party in opposition at both levels of government.

Melaye is in tune with the masses than Adeyemi and other APC bigwigs in Kogi West. James Faleke’s reconciliation with Bello will not help APC much in the district. Faleke is late Abubakar Audu’s running mate in the 2015 governorship poll. He’s been inactive in the state since he lost the party’s mandate to Bello after Audu’s demise. Bello came second in the party primary.

Faleke is currently a federal lawmaker representing Lagos. He and Adeyemi’s political strength does not match Melaye’s in Kogi West. Melaye has over 100 projects to his credit; a contribution neither Adeyemi, Faleke nor Bello has made to the district. Call it uncivilized, Melaye’s politicking is admired by his people. His comical utterances and songs has won him the hearts of the population who sees other politicians as arrogant and inaccessible.

Melaye is a grassroots politician and popular in Kogi West. He stands a chance as none of the major opposition candidates in the governorship election hails from Kogi West. Based on the prominence of ethnic voting in the state, Melaye would lose if a strong opposition governorship candidate like Bello hails from Kogi West. Favored by these odds, Melaye (PDP) would defeat Adeyemi (APC) in the senatorial rerun election. In the same vein, for governorship, Musa Wada of the PDP would garner more votes than Yahaya Bello of the APC in Kogi West.

Governorship Election Outcome

Bello’s underperformance, mis-governance, dwindling admiration, and the odd-against ethnic voting permutation would deter his win. PDP’s Wada would get bulk ethnic votes in Kogi East. Melaye’s senatorial rerun coincidence would earn Wada majority vote in Kogi West. Natasha Akpoti would split Bello’s bulk vote in Kogi Central. The lowest of Wada’s vote would come from the district, while highest would come from Kogi East.

In a free, fair and credible contest, PDP’s Musa Wada would defeat APC’s Yahaya Bello. But the election is not going to be free; not going to be fair; and not going to be credible. Thugs would disperse voters and smash ballot boxes in Wada’s stronghold. The security agencies won’t arrest disruptors, and would be grossly partisan. Above all, the Independent National Electoral Commission would be ‘remote controlled’ by the ‘powers that be’. Several votes would be cancelled and the election would be declared inconclusive.

Virtually all the election winning indicators point to Wada’s emergence, but the pundit foresees Kogi 2019 governorship election ending with a rerun, and if it does, APC’s Yahaya Bello would ultimately be declared winner.

Note: Foretelling the outcome of an election doesn’t mean the writer has access to one sacred information or the election winning strategy of any candidate. Assessing candidates’ fortes and flaws to foretell election results is a common practice in developed nations. This doesn’t mean the pundits are demeaning the electoral process or influencing election results. Bayelsans and Kogites have already decided who they would vote for, and nothing – not this prediction – can easily change their mind.

Omoshola Deji is a political and public affairs analyst. He wrote in via mo******@***oo.com

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are purely of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the position of Business Post Nigeria on the subject matter.

Feature/OPED

Why Digital Trust Matters: Secure, Responsible AI for African SMEs?

By Kehinde Ogundare

For years, security for SMEs across sub-Saharan Africa meant metal grilles and alarm systems. Today, the most significant risks are invisible and growing faster than most businesses realise.

Artificial Intelligence has quietly embedded itself into everyday operations. The chatbot responding to customers at midnight, the system forecasting inventory requirements, and the software identifying unusual transactions are no longer experimental technologies. They are becoming standard features of modern business tools.

Last month’s observance of Safer Internet Day on February 10, themed ‘Smart tech, safe choices’, marked a pivotal moment. As AI adoption accelerates, the conversation must shift from whether businesses should use AI to how they deploy it responsibly. For SMEs across Africa, digital trust is no longer a technical consideration. It is a strategic business imperative.

The evolving threat landscape

Cybersecurity threats facing sub-Saharan African SMEs have moved well beyond basic phishing emails. Globally, cybercrime costs are projected to reach $10.5 trillion this year, fuelled by generative AI and increasingly sophisticated social engineering techniques. Ransomware attacks now paralyse entire operations, while other threats quietly extract sensitive customer data over extended periods.

The regional impact is equally significant. More than 70% of South African SMEs report experiencing at least one attempted cyberattack, and Nigeria faces an average of 3,759 cyberattacks per week on its businesses. Kenya recorded 2.54 billion cyber threat incidents in the first quarter of 2025 alone, whilst Africa loses approximately 10% of its GDP to cyberattacks annually.

The hidden risk of fragmentation

A common but often overlooked vulnerability lies in digital fragmentation.

In the early stages of growth, SMEs understandably prioritise affordability and agility. Over time, this can result in a patchwork of disconnected applications, each with separate logins, security standards, and privacy policies. What begins as flexibility can involve operational complexity.

According to IBM Security’s Cost of a Data Breach Report, companies with highly fragmented security environments experienced average breach costs of $4.88 million in 2024.

Fragmented systems create blind spots; each additional data transfer between applications increases exposure. Inconsistent security protocols make governance harder to enforce. Limited visibility reduces the ability to detect anomalies early. In practical terms, complexity increases risk.

Privacy-first AI as a competitive differentiator

As AI capabilities become embedded in business software, SMEs face a choice about how they approach these powerful tools. The risks are not merely theoretical.

Consumers across Africa are becoming more aware of data rights and are willing to walk away from businesses that cannot demonstrate trustworthiness. According to KPMG’s Trust in AI report, approximately 70% of adults do not trust companies to use AI responsibly, and 81% expect misuse. Meanwhile, studies also show that 71% of consumers would stop doing business with a company that mishandles information.

Trust, once lost, is difficult to rebuild. In the digital age, a single data leak can destroy a reputation that took ten years to build. When customers share their payment details or purchase history, they extend trust. How you handle that trust, particularly when AI processes their data, determines whether they return or take their business elsewhere.

Privacy-first, responsible AI design means building intelligence into business systems with data protection, transparency and ethical use embedded from the outset. It involves collecting only necessary information, storing it securely, being transparent about how AI makes decisions, and ensuring algorithms work without compromising customer privacy. For SMEs, this might mean choosing inventory software where predictive AI runs on your own data without sending it externally, or customer service platforms that analyse patterns without exposing individual records. When AI is built responsibly into unified platforms, it becomes a competitive advantage: you gain operational efficiency whilst demonstrating that customer data is protected, not exploited.

Unified platforms and operational resilience

The solution lies in rethinking digital infrastructure. Rather than accumulating disparate tools, businesses need unified platforms that integrate core functions whilst maintaining consistent security protocols.

A unified approach means choosing cloud-based platforms where functions share common security standards, and data flows seamlessly. For a manufacturing SME, this means inventory management, order processing and financial reporting operate within a single security framework.

When everything operates cohesively, security gaps diminish, and the attack surface shrinks. And the benefits extend beyond risk reduction: employees spend less time on administrative friction, customer data stays consistent, and platforms enable secure collaboration without traditional infrastructure costs.

Safer Internet Day reminds us that the digital world requires active stewardship. For SMEs across the African continent who are navigating complex threats whilst harnessing AI’s potential, digital trust is foundational to sustainable growth. Security, privacy and responsible AI are essential characteristics of any technology infrastructure worth building upon. Businesses that embrace unified, privacy-first platforms will be more resilient against cyber threats and better positioned to earn and maintain trust. In a market where trust is currency, that advantage is everything.

Kehinde Ogundare is the Country Head for Zoho Nigeria

Feature/OPED

Iran-Israel-US Conflict and CBN’s FX Gains: A Stress Test for Nigeria’s Monetary Stability

By Blaise Udunze

At the 304th policy meeting held on Wednesday, the 25th February, the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) Monetary Policy Committee cut the rate by 50 basis points to 26.5 per cent from 27 per cent, which has been widely described as a cautious transition from prolonged tightening to calibrated easing. The CBN stated that the decision followed 11 consecutive months of disinflation. The economy witnessed headline inflation easing to 15.10 per cent in January 2026, and food inflation falling sharply to 8.89 per cent. Foreign reserves are climbing to $50.45 billion, their highest level in 13 years. The Purchasing Managers’ Index is holding at an expansionary 55.7 points.

As reported in the paper, no doubt that the macroeconomic narrative appears encouraging. On a closer scrutiny, the sustainability of these gains is now being tested by forces far beyond the apex bank’s policy corridors. This is as a result of the clear, direct ripple effect of the escalating conflict between Iran and Israel, with direct military involvement from the United States, which has triggered one of the most significant geopolitical energy shocks in decades. For Nigeria, the timing is delicate. Just as the CBN signals confidence in disinflation and stability, global volatility threatens to complicate and possibly distort its monetary path.

The rate cut, though welcomed by many analysts, must be understood in context. Nigeria remains in an exceptionally high-rate environment. An MPR of 26.5 per cent is still restrictive by any standard. The Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) remains elevated at 45 per cent for commercial banks, and this effectively sterilises nearly half of deposits, while liquidity ratios are tight, and lending rates to businesses often exceed 30 per cent once risk premiums are included. The adjustment is therefore incremental, not transformational.

The Director/CEO of the Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise (CPPE), Dr. Muda Yusuf, has repeatedly noted that Nigeria’s deeper challenge lies in weak monetary transmission. According to him, even when the benchmark rate falls, structural rigidities, high CRR, elevated deposit costs, macroeconomic uncertainty, and crowding-out from government borrowing prevent meaningful relief from reaching manufacturers, SMEs, agriculture, and other productive sectors. Monetary easing, without structural reform, risks becoming cosmetic. The point is that even before structural reforms take effect, the fact is that an external shock will first reshape the landscape.

The Iran-Israel conflict and US involvement have reignited fears in global energy markets. Joint U.S. and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets and retaliatory missile exchanges across the Gulf have unsettled oil traders. Brent crude, already rising in anticipation of escalation, surged toward $70-$75 per barrel and could climb higher if shipping through the Strait of Hormuz, through which nearly 20 per cent of global oil supplies pass, faces disruption. It is still an irony that a major crude exporter is also an importer of refined petroleum products.

Higher crude prices offer a theoretical windfall. For Nigeria’s economy, it is well known that oil remains its largest source of foreign exchange and accounts for roughly 50 per cent of government revenue. The good thing is that rising prices could boost reserves, improve forex liquidity, strengthen the naira, and ease fiscal pressures. In theory, this external cushion could support macroeconomic stability and reinforce the CBN’s easing posture.

However, the upside is constrained by structural weaknesses. Nigeria’s oil production remains below optimal capacity. A significant portion of crude exports is tied to long-term contracts, limiting immediate gains from spot price surges. As SB Morgen observed in its analysis, Nigeria’s “windfall” is volatile and limited by soft production performance.

More critically, Nigeria’s dependence on imported refined products exposes it to imported inflation. Rising global crude prices increase the cost of petrol, diesel, jet fuel and gas. With fuel subsidies removed, these increases are passed directly to consumers and businesses. Depot pump prices have already adjusted upward amid Middle East tensions.

Energy costs are a primary driver of Nigeria’s inflation, and this has remained sacrosanct. When fuel prices rise, transportation, logistics, food distribution, power generation, and manufacturing costs will definitely skyrocket, as well as the inflationary impulse spreads quickly through the economy. This will push households to face higher food and transportation costs. Businesses see shrinking margins. Real incomes erode.

Thus, the same oil shock that boosts government revenue may simultaneously reignite inflationary pressure, precisely at a moment when the CBN has begun cautiously easing policy.

This dynamic introduces a difficult policy dilemma, even as this could be for the fragile gains of the MPC. This is to say that if energy-driven inflation resurges, the CBN may be forced to pause or reverse its easing cycle. It is clearly spelt that high inflation typically compels tighter monetary conditions. As Yusuf warned, geopolitical headwinds that elevate inflation often push central banks toward higher interest rates. A renewed tightening would strain credit conditions further, undermining growth prospects.

There is also the risk of money supply expansion. Increased oil revenues, once monetised, can expand liquidity in the domestic system. Historically, surges in oil receipts have been associated with monetary growth, inflationary pressure, and exchange rate volatility. Without sterilisation discipline, a revenue boost could ironically destabilise macro fundamentals.

The exchange rate dimension compounds the complexity. Heightened geopolitical risk, just as it is currently playing out with the Iran-Israel conflict, often triggers global flight to safety. This will eventually lure investors to retreat to U.S. Treasuries and gold. Emerging markets face capital outflows. If it happens that foreign portfolio investors withdraw from Nigeria’s fixed-income market in response to global uncertainty, pressure on the naira could intensify.

Already, the CBN has demonstrated sensitivity to exchange rate dynamics by intervening to prevent excessive naira appreciation. A sharp rate cut in the midst of global volatility could destabilise carry trades and spur dollar demand. What should be known is that the 50-bps reduction reflects not just domestic disinflation, but global risk management such as geopolitical tensions, oil prices, and foreign investor sentiment.

Beyond macroeconomics, geopolitical implications carry security concerns. Analysts warn that a widening Middle East conflict could embolden extremist narratives across the Sahel and it directly has security consequences for Nigeria and the broader region. Groups such as Boko Haram and ISWAP may exploit anti-Western framing to recruit and mobilise more followers in the Sahel region, thereby giving the extremist groups new propaganda opportunities. The pebble fear is that a diversion of Western security resources away from West Africa could create regional vacuums. What the Nigerian economy will begin to experience is that security instability will disrupt agricultural output, logistics corridors, and investor confidence, feeding back into inflation and slow economic growth, and as ripple effects, the economy becomes weaker.

Nigeria’s diplomatic balancing act adds another layer of fragility because it is walking on a tactful tightrope. The country is trying not to upset anyone, but maintains cautious neutrality, urging restraint while preserving ties with Western allies and Middle Eastern partners. Yet rising tensions globally between major powers, including Russia and China, complicate the geopolitical chessboard. Invariably, this will have a direct impact as trade flows, remittances, and investment patterns may change unexpectedly, affecting Nigeria’s economy.

With the current conflict in the Middle East, the prospects for economic growth also face renewed strain or are under increased pressure. The stock markets in developed countries have been fluctuating a lot because people are worried that there will be problems with the energy supply. If the whole world does not grow fast, then people will use less oil over time. This means that the good things that happen to Nigeria because of oil prices will probably not last, and any extra money Nigeria gets from oil prices now will be lost. Nigeria will not get to keep the money from high oil prices for a long time. The oil prices will affect Nigeria. Then the effect will go away. One clear thing is that since Nigeria relies heavily on oil exports, this commodity dependence exposes the country to significant risk.

Meanwhile, Nigeria’s domestic fundamentals remain structurally challenged. The recapitalisation of banks, with 20 of 33 institutions meeting new capital thresholds, strengthens resilience, but does not guarantee credit expansion into productive sectors. Banks continue to prefer risk-free government securities over private lending in uncertain environments.

Fiscal discipline remains essential. Elevated debt service obligations absorb substantial revenue. Election-related spending poses upside inflation risks. This understanding must be adhered to, that without credible deficit reduction and revenue diversification, monetary easing may be undermined by fiscal expansion.

At the moment, given the current global and domestic uncertainties, the 50 per cent interest cut rate appears less like a pivot toward growth and more like a signal of cautious optimism under conditional stability. The policy decision is based on several key expectations with the assumptions that disinflation will persist, exchange rate stability will hold, and global conditions will not deteriorate dramatically.

But the Iran-Israel-U.S. conflict introduces uncertainty into all three assumptions, which is wrongly perceived as behind the rate cut that inflation will keep coming down, that the exchange rate will stay stable, and global conditions won’t worsen, are all undermined by the unfolding conflict.

If the global oil prices rise sharply and fuel becomes more expensive locally, overall prices in the economy could increase again, which means inflation could accelerate. Another dangerous trend is that if foreign investors pull capital out of Nigeria, exchange rate stability could weaken, seeing the naira coming under pressure. If global growth slows, export earnings could decline. Each of these scenarios would constrain the CBN’s flexibility.

This is not to dismiss potential upsides. Higher oil prices, if production improves, could bolster reserves and moderate fiscal deficits. Forex liquidity could strengthen the naira. Investment in upstream oil and gas could gain momentum. Historically, crude price increases have correlated with improved GDP performance and stock market optimism in Nigeria.

Yet history also warns of volatility. A good example is during the 2022 Ukraine conflict, oil prices spiked above $100 per barrel, which created a potential revenue windfall for oil-exporting countries, but Nigeria struggled to translate that temporary advantage into sustained economic improvement. Inflation persisted. In the case of Nigeria, the deep-rooted systemic or structural weaknesses and inefficiency diluted the benefits that should have been gained.

The lesson is clear because temporary external windfalls or short-term luck cannot substitute for structural and deep internal economic reforms.

The point is that sustainable development demands diversification beyond oil, to strengthening multiple parts of its economy at the same time, such as improved refining capacity, infrastructure investment, agricultural security, logistics efficiency, and fiscal consolidation. Monetary policy, as the action taken by the CBN at the MPC meeting by adjusting interest rates or attempting to control money supply, can anchor expectations and moderate volatility, but it cannot build productive capacity; it will only help to reduce short-term economic swings.

The CBN’s decision to cut the interest rate appears cautious. It is not a bold shift but rather a small adjustment. This shows that the bank is being careful and optimistic about the economy. It also knows that there are still problems. The trouble in the Middle East, like the fighting that affects the oil supply, reminds the people in charge that Nigeria’s economy is closely tied to what happens with energy around the world. This includes things like inflation, the value of money, and how fast the economy grows.

Until structural reforms reduce dependence on volatile oil cycles and imported fuel, Nigeria’s monetary policy will remain reactive to external crises. To really make the economy strong and stable, Nigeria needs to make some changes. It requires resilience against geopolitical storms.

The MPC has taken a step. Whether it marks a turning point depends less on 50 basis points and more on how Nigeria navigates a world increasingly defined by conflict-driven volatility.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: bl***********@***il.com

Feature/OPED

How Secure Is Nigeria…?

Prince Charles Dickson, PhD

A country’s security is not measured by the number of uniforms on the road. It is measured by whether an ordinary mother can sleep without one ear open, whether a trader can return from the market without rehearsing ransom instructions in her head, whether a doctor can drive to an emergency without praying not to meet a checkpoint more dangerous than the patient he is trying to save.

Nigeria today has security everywhere and safety nowhere.

That is the paradox. We have the architecture of force, but not the confidence of protection. We have commands, theatres, operations, task forces, and an alphabet soup of interventions. Yet for many citizens, insecurity still arrives first, and the state arrives later, sometimes not at all. Even the federal government has repeatedly acknowledged that the police ought to be the frontline institution for internal security, and that modern policing requires better training, technology, and professionalism. It has also admitted that police training facilities have fallen into serious dilapidation and need an overhaul.

So, the question is no longer whether Nigeria has security institutions. It does. The more uncomfortable question is whether the current federal policing model, as designed and practised, is still fit for the country we have become.

The Nigeria Police Force remains a centrally commanded institution, with authority cascading from the Inspector-General through Deputy Inspectors-General, Assistant Inspectors-General, Commissioners, and downward through the ranks. Administratively, it is split into eight departments. On paper, that looks orderly, neat, even reassuring. But Nigeria is not a paper country. It is a noisy federation of griefs, distances, fractures, ambitions, and emergencies. A chain of command that may satisfy legal elegance can also produce operational remoteness, delayed responsiveness, and a politics of policing in which local pain must wait for federal mood.

This is where the politics begins.

Who does the police truly serve in practice: the republic, the constitution, the citizen, or the powerful? That question hurts because Nigerians already know the answer in their bones. More than 100,000 officers are reportedly assigned to VIP protection out of an estimated 371,800 personnel. That means a startling share of police manpower is concentrated around the elite while ordinary communities make do with thin patrols, slow response, and the old folklore of “call anybody you know.” In effect, the state has built a two-tier policing culture: one for those with sirens, another for those with silence.

And when public policing weakens, Nigeria reaches reflexively for the military.

That too has become normal, and that is precisely the problem. The country now lives under a strange internal-security arrangement in which police are constitutionally primary, but the military increasingly occupies the emotional and operational space of first responder. Analysts have described this as a role lost to the military: a situation in which soldiers are overstretched, police are underpowered, and the public is trapped in a dangerous vacuum between both. New task forces and command theatres may project action, but they can also conceal a deeper institutional confession: that the police have not been built to carry the burden of modern internal security.

This is why I remain cautious when the state celebrates “combined operations,” “joint architecture,” and the multiplication of theatres. Coordination is necessary, yes. But coordination is not the same thing as competence. A nation cannot keep responding to civil insecurity as though every problem is a battlefield problem. Kidnapping, urban crime, community violence, organised extortion, digital fraud, and intelligence-led prevention all require policing that is forensic, local, trusted, and fast. The 21st century does not only ask for men with rifles. It asks for institutions with memory, data, integrity, and legitimacy.

And legitimacy is expensive.

You cannot demand ethical policing from men and women whom the system has abandoned to shabby welfare, poor housing, weak equipment, and thinning morale. Reuters reported in late 2025 that a low-ranking police officer earned about ₦80,000 monthly net pay. Around the same period, former IGP Mike Okiro publicly warned that economic hardship, poor welfare, and years of neglect were crippling police morale. An investigation by The ICIR in February 2026 described dilapidated barracks in Lagos where police families live inside cracked, ageing buildings that are tragedies waiting to happen. This is not merely a welfare issue. It is a security issue. A poorly paid, poorly housed, poorly equipped officer is not just vulnerable. He is recruitable by temptation.

So, is state police the answer?

Maybe. But only maybe.

The argument for state police is no longer fringe. In February 2024, federal and state authorities publicly agreed on the need for state police as insecurity worsened. As of March 1, 2026, the Senate says it intends to complete the constitutional amendment for state police before the end of the year, while also discussing safeguards against abuse by governors. That last phrase matters. Because state police can become either the localisation of safety or the localisation of tyranny. In the hands of disciplined constitutionalism, it may deepen community intelligence, faster response, and contextual policing. In the hands of bad politics, it could become a uniform errand boy for governors, godfathers, and vendetta.

So, let us not romanticise decentralisation. A broken institution does not become healthy merely by being copied 36 times.

State police without safeguards, independent oversight, diversity protections, judicial remedies, professional standards, and funding clarity may only decentralise abuse. Yet federal policing without radical reform has already produced a structure too centralised to feel local, too politicised to feel neutral, and too stretched to feel present. That is the Nigerian trap: the old model is failing, but the new model can also fail if designed as another elite bargain.

The real issue, then, is deeper than federal versus state. It is whether Nigeria truly wants citizen-centred policing or merely a rearrangement of command.

For years, we have treated the police as a ceremonial symbol, a regime accessory, or a checkpoint economy. We post them at politicians’ gates, attach them to convoys, and then act surprised when villages, highways, schools, and neighbourhoods feel abandoned. We invoke reform, but often mean procurement. We invoke modernisation, but often mean new uniforms and fresh rhetoric. Yet even the Presidency has admitted that true reform goes beyond repainting buildings or buying weapons. It requires a fundamental overhaul of institutional mentality and memory. That, perhaps, is the most honest sentence said about the police in recent years.

How secure is Nigeria?

Not secure enough to keep pretending that force projection is the same as public safety.

Until the police are rebuilt as a serious, modern, welfare-backed, intelligence-driven, citizen-facing institution, we will keep living inside a republic where the hierarchy is protected, the theatres are busy, the communiqués are polished, and the people remain one phone call away from abandonment—May Nigeria win!

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn