Feature/OPED

Socioeconomic Challenges and Options Before the Federal Government

By Jerome-Mario Utomi

Aside from the time-honoured belief that the poverty of any country is felt by the quality and quantity of food to its citizens, it is important to state abinitio that this piece was principally inspired by two separate but related promptings.

First is the study report which among other observations states that over the past century in the United States of America (USA), there exists a shift in the locations and occupations of urban consumers.

It explained that in 1900, about 40% of the total population was employed on the farm, and 60% lived in rural areas. Today, the respective figures are only about 1% and 20%. Over the past half-century, the number of farms has fallen by a factor of three.

As a result, the ratio of urban eaters to rural farmers has markedly risen, giving the food consumer a more prominent role in shaping the food and farming system. The changing dynamic has also played a role in public calls to reform federal policy to focus more on the consumer implications of the food supply chain.

The second is the argument by Frances Stewart that the development-security nexus has become central to the development and peace-building enterprises.

He considers three types of connections between security and development, both nationally and globally: (a) security as an objective, (b) security as an instrument and (c) development as an instrument.

Given these connections, he argued that security policies may become part of development policy because in so far as they enhance security, they will contribute to development.

Conversely, development policies may become part of security policy because enhanced development increases security. Stewart finds that ‘societal progress requires reduced insecurity’ and that more inclusive and egalitarian development is likely to enhance security.’

From this spiralling awareness, the question may be asked; as a nation, what do make out of the above given heightened insecurity in the country which has resulted in incessant killings of farmers majorly in the North central part of the country and Nigeria as a whole and pathetically rendered us a country in dire need of peace and social cohesion among her various socio-political groups?

How do we arrest the situation given the fact that all its signs portend grave danger to the nation and are laced with the capacity to ‘engineer food insecurity in the country?

How do we as a nation tackle the fact that the number of farms has fallen caused by a factor attributable to insecurity? What plan is in place to manage the nagging reality that the ratio of urban eaters to rural farmers has markedly risen as a result of farmers that fled their farms/villages in order to secure their lives? Is the federal government mindful of the worrying awareness that by 2050, global consumption of food and energy is expected to double as the world’s population and incomes grow, while climate change is expected to have an adverse effect on both crop yields and the number of arable acres? What are our security and development objectives? What are the instruments targeted at achieving these objectives?

Exacerbating the situation is the belief in some quarters that since independence, the country has demonstrated that “there is no development plan (Fiscal policies, socioeconomic plans and poverty alleviations programmes) which has achieved its core objectives. There is always a disturbing laxity in marching plan targets with practical and unfailing consistency. The result is that the country remains one of the most politically and economically disarticulated countries in the world”.

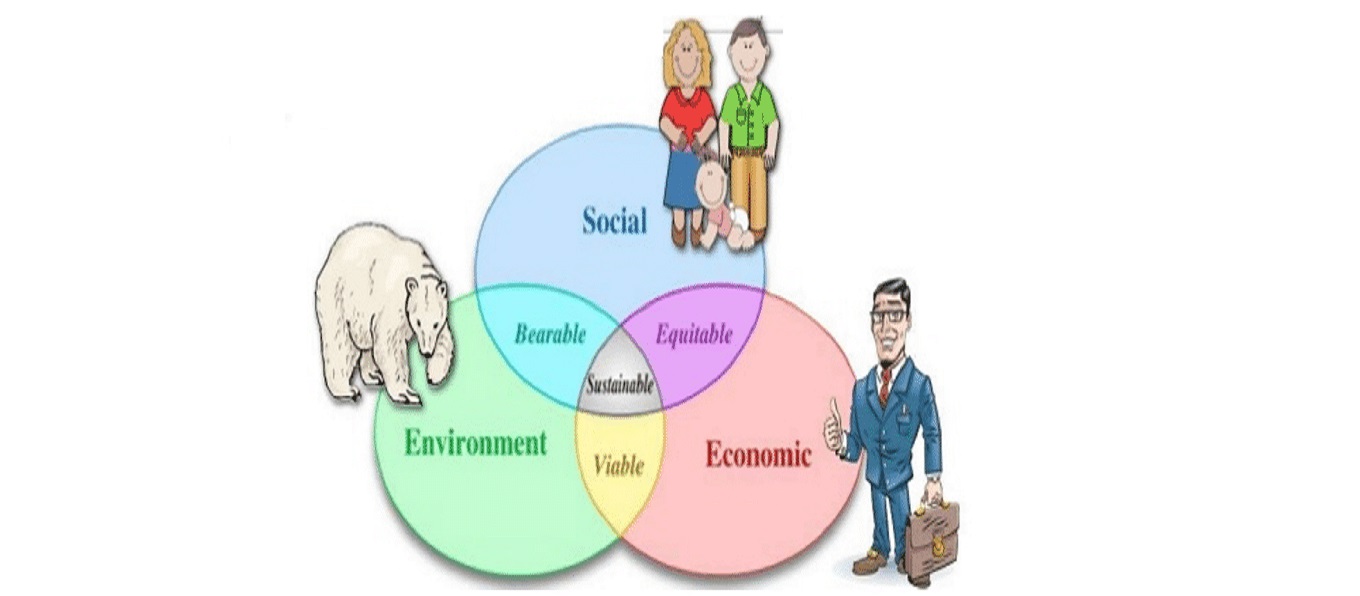

Accordingly, as we prod over these concerns, it will be relevant to the present discourse to add that for any programme/action to be typified as development-based/focused, development practitioners believe that such programme progress should entail an all-encompassing improvement, a process that builds on itself and involve both individuals and social change.

Requires growth and structural change, with some measures of distributive equity, modernization in social and cultural attitudes, a degree of political transformation and stability, an improvement in health and education so that population growth stabilizes, and an increase in urban living and employment.

In the same vein, it is public knowledge that throughout the early decades, Nigeria paid little attention to what constitutes sustainable development.

Such conversation, however, gained global prominence via the United Nations introduction, adoption and pursuit of the Millennium Development Goals, MDGs, which lasted between the years 2000 and 2015. And was among other intentions aimed at eradicating extreme poverty and hunger as well as achieve universal primary education, promote gender equality, reduce child mortality, improve maternal health among others.

Without going into specific concepts or approaches contained in the performance index of the programme, it is evident that Nigeria and the majority of the countries performed below average. And, it was this reality and other related concerns that conjoined to bring about 2030 sustainable agenda- a United Nation initiative and successor programme to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)- with a collection of 17 global goals formulated among other aims to promote and cater for people, peace, planet, and poverty.

And has at its centre; partnership and collaboration, ecosystem thinking, co-creation and alignment of various intervention efforts by the public and private sectors and civil society.

Certainly, Nigeria is plagued with development challenges such as widespread poverty, insecurity, corruption, the gross injustice and ethnic politics-and in dire need of attention from interventionist organizations (private and civil society organizations) as demanded by the agenda.

But, instead of the government’s passionate plea for sustainable partnership and productive collaboration receiving targeted positive responses from private organizations and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), such request often always elicits from critical minds and corporate organizations nothing but jigsaw:

If it has been said that government has no business in business, what business does the private sector have in helping the government to do its business of providing quality governance to the populace which is the instrumentality of participatory democracy and the election of leaders conferred on them? The reason for this state of affairs is not to be unconnected with transparency challenges on the part of the government.

To the private and civil society organizations, such a response option offers a more considerably reduced risk as no organization may be disposed to investing in an environment that is devoid of transparency and accountability.

Aside from the transparency and accountability challenge, with the constant killing, wanton destruction of property and palpable insecurity in the states, farmers have abandoned their farms to save their lives.

The effect is that food production and supplies in the country are openly threatened and may totally cut off months ahead.

The implication of this scenario if allowed is that the country is exposed to a harsher food crisis. It also sends a gory signal/message that what is to come in terms of escalation in the prices of food and agricultural produce and supplies promises to be scary.

Bearing this in mind, the question again, may be asked; what is the way forward? What are the best ways that the President Muhammadu Buhari led federal government can save Nigeria and Nigerians from this impending food crisis? What proactive steps and options are available before the federal government?

If the federal government wants to progress and development for the nation, there is no reason why everything that will lead to success must not be done. And such effort must first and fundamentally focus on developing socioeconomic policies that are not only people-focused but equipped with a clear definition of our problem as a nation, the goals to be achieved, and the means chosen to address the problems/and to achieve the goals.

As an incentive, such policies/programmes must focus on protecting the lives and property of Nigerians, job creation, development of strong institutions as well as infrastructural development.

By Jerome-Mario Utomi is the Programme Coordinator (Media and Public Policy), Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA), Lagos. He could be reached via je*********@***oo.com/08032725374.

Feature/OPED

Brent’s Jump Collides with CBN Easing, Exposes Policy-lag Arbitrage

Nigeria is entering a timing-sensitive macro set-up as the oil complex reprices disruption risk and the US dollar firms. Brent moved violently this week, settling at $77.74 on 02 March, up 6.68% on the day, after trading as high as $82.37 before settling around $78.07 on 3 March. For Nigeria, the immediate hook is the overlap with domestic policy: the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has just cut its Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) by 50 basis points to 26.50%, whilst headline inflation is still 15.10% year on year in January.

“Investors often talk about Nigeria as an oil story, but the market response is frequently a timing story,” said David Barrett, Chief Executive Officer, EBC Financial Group (UK) Ltd. “When the pass-through clock runs ahead of the policy clock, inflation risk, and United States Dollar (USD) demand can show up before any oil benefit is felt in day-to-day liquidity.”

Policy and Pricing Regime Shift: One Shock, Different Clocks

EBC Financial Group (“EBC”) frames Nigeria’s current set-up as “policy-lag arbitrage”: the same external energy shock can hit domestic costs, FX liquidity, and monetary transmission on different timelines. A risk premium that begins in crude can quickly show up in delivered costs through freight and insurance, and EBC notes that downstream pressure has been visible in refined markets, with jet fuel and diesel cash premiums hitting multi-year highs.

Market Impact: Oil Support is Conditional, Pass-through is Not

EBC points out that higher crude is not automatically supportive of the naira in the short run because “oil buffer” depends on how quickly external receipts translate into market-clearing USD liquidity. Recent price action illustrates the sensitivity: the naira was quoted at 1,344 per dollar on the official market on 19 February, compared with 1,357 a week earlier, whilst street trading was cited around 1,385.

At the same time, Nigeria’s inflation channel can move quickly even during disinflation: headline inflation eased to 15.10% in January from 15.15% in December, and food inflation slowed to 8.89% from 10.84%, but energy-led transport and logistics costs can reintroduce pressure if the risk premium persists. EBC also points to a broader Nigeria-specific reality: the economy grew 4.07% year on year in 4Q25, with the oil sector expanding 6.79% and non-oil 3.99%, whilst average daily oil production slipped to 1.58 million bpd from 1.64 million bpd in 3Q25. That mix supports external-balance potential, but it also underscores why the domestic liquidity benefit can arrive with a lag.

Nigeria’s Buffer Looks Stronger, but It Does Not Eliminate Sequencing Risk

EBC sees that near-term external resilience is improving. The CBN Governor said gross external reserves rose to USD 50.45 billion as of 16 February 2026, equivalent to 9.68 months of import cover for goods and services. Even so, EBC views the market’s focus as pragmatic: in a risk-off tape, investors tend to price the order of transmission, not the eventual balance-of-payments benefit.

In the near term, EBC expects attention to rotate to scheduled energy and policy signposts that can confirm whether the current repricing is a short, violent adjustment or a more durable regime shift, including the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) Short-Term Energy Outlook (10 March 2026), OPEC’s Monthly Oil Market Report (11 March 2026), and the U.S. Federal Reserve meeting (17 to 18 March 2026). On the domestic calendar, the CBN’s published schedule points to the next Monetary Policy Committee meeting on 19 to 20 May 2026.

Risk Frame: The Market Prices the Lag, Not the Headline

EBC cautions that outcomes are asymmetric. A rapid de-escalation could compress the crude risk premium quickly, but once freight, insurance, and hedging behaviour adjust, second-round effects can linger through inflation uncertainty and a more persistent USD bid.

“Oil can act as a shock absorber for Nigeria, but only when the liquidity channel is working,” Barrett added. “If USD conditions tighten first and domestic pass-through accelerates, the market prices the lag, not the headline oil price.”

Brent remains an anchor instrument for tracking this timing risk because it links energy-led inflation expectations, USD liquidity, and emerging-market risk appetite in one market. EBC Commodities offering provides access to Brent Crude Spot (XBRUSD) via its trading platform for following energy-driven macro volatility through a single instrument.

Feature/OPED

Gen Alpha: Africa’s Digital Architects, Not Your Target Audience

By Emma Kendrick Cox

This year, the eldest Gen Alpha turns 16.

That means they aren’t just the future of our work anymore. They are officially calling for a seat at the table, and they’ve brought their own chairs. And if you’re still calling this generation born between 2010 and 2025 the iPad generation, then I hate to break it to you, but you’re already obsolete. To the uninitiated, they look like a screen-addicted mystery. To those of us paying attention, they are the most sophisticated, commercially potent, and culturally fluent architects Africa has ever seen.

Why? Because Alphas were not born alongside the internet. They were born inside it. And by 2030, Africa will be home to one in every three Gen Alphas on the planet.

QWERTY the Dinosaur

We are witnessing the rise of a generation that writes via Siri and speech-to-text before they can even hold a pencil. With 63% of these kids navigating smartphones by age five, they don’t see a QWERTY keyboard as a tool. They see it as a speed bump, the long route, an inefficient use of their bandwidth. They don’t need to learn how to use tech because they were born with the ability to command their entire environment with a voice note or a swipe.

They are platform agnostic by instinct. They don’t see boundaries between devices. They’ll migrate from an Android phone to a Smart TV to an iPhone without breaking their stride. To them, the hardware is invisible…it’s the experience that matters.

They recognise brand identities long before they know the alphabet. I share a home with a peak Gen Alpha, age six and a half (don’t I dare forget that half). When she hears the ding-ding-ding-ding-ding of South Africa’s largest bank, Capitec’s POS machine, she calls it out instantly: “Mum! Someone just paid with Capitec!” It suddenly gives a whole new meaning to the theory of brand recall, in a case like this, extending it into a mental map of the financial world drawn long before Grade 2.

And it ultimately lands on this: This generation doesn’t want to just view your brand from behind a glass screen. They want to touch it, hear it, inhabit it, and remix it. If they can’t live inside your world, you’re literally just static.

The Uno Reverse card

Unlike any generation we’ve seen to date, households from Lagos to Joburg and beyond now see Alphas hold the ultimate Uno Reverse card on purchasing power. With 80% of parents admitting their kids dictate what the family buys, these Alphas are the unofficial CTOs and Procurement Officers of the home:

-

The hardware veto: Parents pay the bill, but Alphas pick the ISP based on Roblox latency and YouTube 4K buffers.

-

The Urban/Rural bridge: In the cities, they’re barking orders at Alexa. In rural areas, they are the ones translating tech for their families and narrowing the digital divide from the inside out.

-

The death of passive: I’ll fall on my sword when I say that with this generation, the word consumer is dead. It implies they just sit there and take what you give them, when, on the contrary, it is the total opposite. Alphas are Architectural. They are not going to buy your product unless they can co-author the experience from end to end.

As this generation creeps closer and closer to our bullseye, the team here at Irvine Partners has stopped looking at Gen Alpha as a demographic and started seeing them as the new infrastructure of the African market. They are mega-precise, fast, and surgically informed.

Believe me when I say they’ve already moved into your industry and started knocking down the walls. The only question is: are you building something they actually want to live in, or are you just a FaceTime call they are about to decline?

Pay attention. Big moves are coming. The architects are here.

Emma Kendrick Cox is an Executive Creative Director at Irvine Partners

Feature/OPED

Why Digital Trust Matters: Secure, Responsible AI for African SMEs?

By Kehinde Ogundare

For years, security for SMEs across sub-Saharan Africa meant metal grilles and alarm systems. Today, the most significant risks are invisible and growing faster than most businesses realise.

Artificial Intelligence has quietly embedded itself into everyday operations. The chatbot responding to customers at midnight, the system forecasting inventory requirements, and the software identifying unusual transactions are no longer experimental technologies. They are becoming standard features of modern business tools.

Last month’s observance of Safer Internet Day on February 10, themed ‘Smart tech, safe choices’, marked a pivotal moment. As AI adoption accelerates, the conversation must shift from whether businesses should use AI to how they deploy it responsibly. For SMEs across Africa, digital trust is no longer a technical consideration. It is a strategic business imperative.

The evolving threat landscape

Cybersecurity threats facing sub-Saharan African SMEs have moved well beyond basic phishing emails. Globally, cybercrime costs are projected to reach $10.5 trillion this year, fuelled by generative AI and increasingly sophisticated social engineering techniques. Ransomware attacks now paralyse entire operations, while other threats quietly extract sensitive customer data over extended periods.

The regional impact is equally significant. More than 70% of South African SMEs report experiencing at least one attempted cyberattack, and Nigeria faces an average of 3,759 cyberattacks per week on its businesses. Kenya recorded 2.54 billion cyber threat incidents in the first quarter of 2025 alone, whilst Africa loses approximately 10% of its GDP to cyberattacks annually.

The hidden risk of fragmentation

A common but often overlooked vulnerability lies in digital fragmentation.

In the early stages of growth, SMEs understandably prioritise affordability and agility. Over time, this can result in a patchwork of disconnected applications, each with separate logins, security standards, and privacy policies. What begins as flexibility can involve operational complexity.

According to IBM Security’s Cost of a Data Breach Report, companies with highly fragmented security environments experienced average breach costs of $4.88 million in 2024.

Fragmented systems create blind spots; each additional data transfer between applications increases exposure. Inconsistent security protocols make governance harder to enforce. Limited visibility reduces the ability to detect anomalies early. In practical terms, complexity increases risk.

Privacy-first AI as a competitive differentiator

As AI capabilities become embedded in business software, SMEs face a choice about how they approach these powerful tools. The risks are not merely theoretical.

Consumers across Africa are becoming more aware of data rights and are willing to walk away from businesses that cannot demonstrate trustworthiness. According to KPMG’s Trust in AI report, approximately 70% of adults do not trust companies to use AI responsibly, and 81% expect misuse. Meanwhile, studies also show that 71% of consumers would stop doing business with a company that mishandles information.

Trust, once lost, is difficult to rebuild. In the digital age, a single data leak can destroy a reputation that took ten years to build. When customers share their payment details or purchase history, they extend trust. How you handle that trust, particularly when AI processes their data, determines whether they return or take their business elsewhere.

Privacy-first, responsible AI design means building intelligence into business systems with data protection, transparency and ethical use embedded from the outset. It involves collecting only necessary information, storing it securely, being transparent about how AI makes decisions, and ensuring algorithms work without compromising customer privacy. For SMEs, this might mean choosing inventory software where predictive AI runs on your own data without sending it externally, or customer service platforms that analyse patterns without exposing individual records. When AI is built responsibly into unified platforms, it becomes a competitive advantage: you gain operational efficiency whilst demonstrating that customer data is protected, not exploited.

Unified platforms and operational resilience

The solution lies in rethinking digital infrastructure. Rather than accumulating disparate tools, businesses need unified platforms that integrate core functions whilst maintaining consistent security protocols.

A unified approach means choosing cloud-based platforms where functions share common security standards, and data flows seamlessly. For a manufacturing SME, this means inventory management, order processing and financial reporting operate within a single security framework.

When everything operates cohesively, security gaps diminish, and the attack surface shrinks. And the benefits extend beyond risk reduction: employees spend less time on administrative friction, customer data stays consistent, and platforms enable secure collaboration without traditional infrastructure costs.

Safer Internet Day reminds us that the digital world requires active stewardship. For SMEs across the African continent who are navigating complex threats whilst harnessing AI’s potential, digital trust is foundational to sustainable growth. Security, privacy and responsible AI are essential characteristics of any technology infrastructure worth building upon. Businesses that embrace unified, privacy-first platforms will be more resilient against cyber threats and better positioned to earn and maintain trust. In a market where trust is currency, that advantage is everything.

Kehinde Ogundare is the Country Head for Zoho Nigeria

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn