Feature/OPED

South Africa Lacks Energy Power in Emerging Multipolar World

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

South Africa undoubtedly boasts its power and integrity on the global stage. South Africa is known as the first economic power in Africa and as a staunch member of many international organizations. It maintains significant regional influence and is a member of the African Union, the Commonwealth of Nations, the BRICS and the G20. With an estimated 62 million (as of 2023) people of diverse cultural origins, South Africa’s economy is sustained by both local and foreign businesses. Today, it has to struggle with power outages, unsuccessful in meeting both domestic and industrial power requirements in the country.

Unlike most of the African countries, South Africa’s economy is the most industrialized and technologically advanced, the second largest economy in Africa, after Egypt and Nigeria. South Africa has a very large energy sector and is currently the only country on the African continent that possesses a nuclear power plant. The country’s primary electricity generator is Eskom, the utility is the largest producer of electricity in Africa.

Eskom’s latest energy availability factor (EAF) data reveals that mismanagement, corruption, poor maintenance, and sabotage caused power station breakdowns. Due to severe mismanagement and corruption at Eskom, the company is $22 billion in debt and unable to meet the demands of the South African power grid. It has resulted in load shedding to prevent a failure of the entire system when the demand for electricity strains the capacity of Eskom’s power-generating system.

China’s Factor in the South African Energy Crisis

China has contemplated support for the South African energy crisis since 2011 it joined BRICS. The latest development was in August 2023 during the 15th BRICS summit held in Johannesburg, South Africa signed a raft of deals with China to help it overhaul its creaky energy sector including upgrading its nuclear power plant as the government seeks to ease a severe energy crisis hobbling the economy.

The agreements, signed with Chinese power companies on the sidelines of the BRICS summit, include upgrades to the electricity transmission and distribution network. “We are moving at the speed of the fastest, we are not going to move at the speed of the slowest,” Electricity Minister Kgosientsho Ramokgopa after signing the deals. China’s power transmission grid network, generation capacity and renewable energy plants are the largest in the world and were set up in a short time and it is this expertise South Africa wanted to learn from, Ramokgopa said.

South Africa’s state utility Eskom has a power supply shortfall of around 4,000 megawatts (MW), accounting for a tenth of its installed capacity and resulting in record power cuts. Its transmission capacity is highly constrained, preventing any alternative power sources from coming online. The bulk of its distribution infrastructure – an array of thousands of transformers and substations supplying power to households – often burns out leading to long hours without power.

China will help to extend the life of Eskom’s coal-fired power plants, offer technology to cut emissions at a lower cost than available elsewhere globally and China might also set up transformer and solar PV panel manufacturing facilities in the country, Ramokgopa said. It will also help South Africa upgrade its nuclear power plant, he added.

President Cyril Ramaphosa noted that China, its biggest trading partner, would supply emergency power equipment worth 167 million rand ($8.9 million) and a grant of around 500 million rand for the power sector, without giving timelines.

According to an April 2024 report from Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center and the African Economic Research Consortium, China has a unique opportunity to drive forward an energy revolution in Africa, but it must first reverse nearly two decades of neglect of green power investments there. Beijing has emerged as the continent’s biggest bilateral trading partner since the start of the century and has financed billions of dollars worth of large-scale infrastructure projects.

In 2021, China’s President Xi Jinping said the country would not build new coal-fired power projects abroad, pledging to deal with climate change by supporting the development of green and low-carbon energy. Although Africa’s green energy potential is one of the highest in the world, Chinese lending and investment have so far provided relatively little support for the continent’s energy transition.

Lending for renewables, such as solar and wind, from China’s two main development finance institutions constituted just 2% of their $52 billion of energy loans from 2000 to 2022, while more than 50% is allocated to fossil fuels. “Given current economic challenges and future energy opportunities, China can play a role in contributing to Africa’s energy access and transition through trade, finance and FDI (foreign direct investment),” the report said.

Chinese development finance institutions have been focused on investing in the extraction and export of commodities to China and in electrification projects. Chinese lending has targeted many of the same sectors that produce the oil and minerals that flow back to China. At least eight hydropower projects financed by the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM), which represent 26% of all hydropower lending, are intended to support the extraction of various metals.

“Although this track has led to export revenues for African economies, African countries are not yet receiving the full benefits of renewable energy technologies,” the report said. In 2022, fossil fuels accounted for around 75% of total electricity generation in Africa and about 90% of energy consumption, the report said.

South Africa and across the rest of Africa, energy has become crucial. Without sustainable energy flow, industrialization is impossible. At the BRICS-Africa Outreach and BRICS Plus Dialogue, China’s leader Xi Jinping made concrete proposals which included: China to launch the Initiative on Supporting Africa’s Industrialization. China plans to harness resources for cooperation with Africa and support Africa in its manufacturing sector, industrialization and economic diversification. China plans to channel more resources into investment and finance industrialization.

Russia’s Renewable Energy Pledges

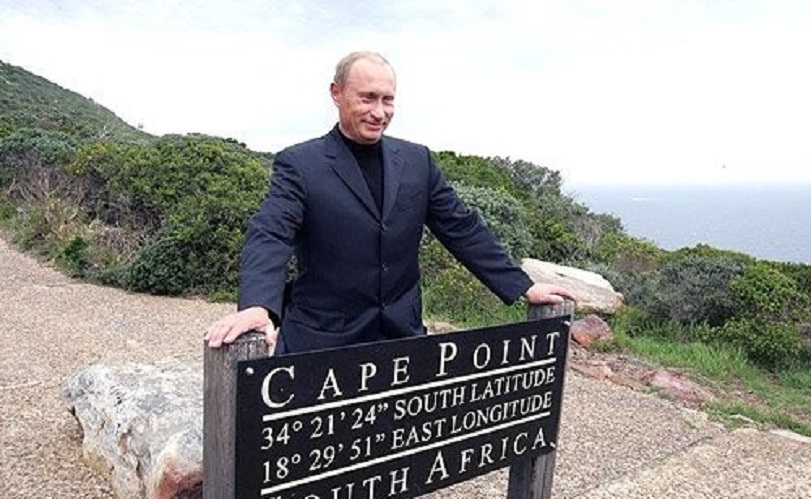

South Africa and Russia have excellent relations. The nuclear energy deal between South Africa and Russia has dominated official discussions over the years. Under Jacob Zuma, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a deal estimated at $76 billion to build Russian-run nuclear energy plants. Until today, that deal remains unrealizable and worse still mentioned in speeches as part of a bilateral agreement. But in the latest developments, South Africa from explicit indications unreservedly supports Russia’s ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine. During Johannesburg’s 15th BRICS summit held in August 2023, nuclear power pledges, with high enthusiasm, were renewed.

Russian Ambassador to South Africa Ilya Rogachev renewed the official pledge that Russia would help South Africa solve the problem of energy shortages. “The Russian Federation is a world leader in the field of nuclear technology. If we talk about cooperation between Russia and South Africa in this area, joint work on expanding nuclear generation in the country can play a key role in solving the problem of electricity shortages in South Africa and can lay the foundation for energy independence and technological sovereignty of the Republic of South Africa,” the diplomat told the local Russian media.

According to him, Russian companies work with advanced technologies and are ready, for their part, to offer expertise and competencies within the framework of appropriate tender procedures. Russia is ready to cooperate in the supply of fuel for nuclear power plants, the construction of new large and small nuclear capacities, the development of floating plants, the construction of a new research reactor, the development of nuclear medicine and so forth. Russia has the desire to strengthen South Africa’s energy security, and in particular, is ready to exchange useful key practices in the field of energy production, distribution and utilization.

European Union and South Africa’s Energy Cooperation

At least in 2021, the European Union has supported its concern over South Africa’s energy difficulties. Even far earlier European Union members have contributed financially. The governments of South Africa, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States of America, along with the European Union, have in November 2021 announced a new ambitious, long-term ‘Just Energy Transition Partnership’ to support South Africa.

According to European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, the European Union kick-started the Just Energy Transition Partnership with South Africa, a first-of-its-kind global initiative for accelerating a just energy transition, and would also outline measures undertaken by the government of South Africa for long-term energy transition. EU is working with a concrete programme at the full cost of $8.5 billion, in addition to what the World Bank Board approved for Eskom, the South African energy Sector.

The President of the United States of America, Joseph R. Biden, said: “The United States is proud to partner with the Government of South Africa and the members of the International Partners Group to support South Africa’s just transition to a cleaner energy future. We welcome the comprehensive JET Investment Plan and fully support South Africa’s economy-wide energy transformation. Our support for South Africa’s clean energy and infrastructure priorities, which include efforts to provide coal miners and affected communities the assistance that they need in this transition, will help South Africa’s clean energy economy thrive.”

BRICS New Development Bank

Much praised BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) New Development Bank was established in 2015 to compete with other multilateral development banks such as the World Bank and IMF. As a multilateral development bank to mobilize resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in emerging markets and developed countries, it has so far limited scope of operations. It dreams of supporting developing countries, but it cannot under the circumstances and is far behind the status of the IMF and World Bank. While the IMF has offices across Africa, the NDB has only a skeleton staff in Russia and South Africa.

Although Bangladesh, Egypt, Uruguay and the United Arab Emirates also joined as members, the NDB still cannot simply compete with the already established multilateral financial institutions. In 2018, the Board of Directors of the New Development Bank approved two infrastructure and sustainable development projects in South Africa and China, with both loans aggregating $600 million. In addition, the NDB offered financial assistance during the coronavirus pandemic. With energy difficulties, there has been no report indicating loans to support South Africa’s energy sector. In future, developing countries craving to become members of BRICS should not expect any development finances from the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) New Development Bank.

World Bank’s Contribution to South Africa’s Energy Sector

Last October 2023, the World Bank approved a $1 billion loan to support South Africa’s energy sector currently experiencing worse conditions including inadequate funds for overhauling, renovation and upgrading. That the World Bank’s loan, at least, would pull South Africa out of its persistent energy crisis that has adversely hit industrial production.

“The loan endorses a significant and strategic response to South Africa’s ongoing energy crisis and the country’s goal of transitioning to a just and low carbon economy,” the World Bank said in its report. But the South African government has often said it needs nearly $80 billion over the next five years to fund its transition to greener energy sources. Energy experts have consistently suggested that South Africa undergo some necessary reforms in its energy sector to address and consequently overcome regular power cuts that have curbed economic growth and industrial production.

South Africa is not the only country experiencing energy shortage and crisis. Energy poverty is pounding some Southern African countries. Nearly all African countries are suffering from acute power deficits. Appreciably China, Russia and other external countries, at least, have shown their uttermost unique contributions to consolidate relations and save South Africa, whose diverse internal problems turn complicated but highly boasts its image as Africa’s economic power on the international stage. With extreme prestige, the United States, Europe, BRICS and the G20 consistently chuckle at the African National Congress (ANC), President Cyril Ramaphosa and the entire population of South Africa.

Feature/OPED

How Christians Can Stay Connected to Their Faith During This Lenten Period

It’s that time of year again, when Christians come together in fasting and prayer. Whether observing the traditional Lent or entering a focused period of reflection, it’s a chance to connect more deeply with God, and for many, this season even sets the tone for the year ahead.

Of course, staying focused isn’t always easy. Life has a way of throwing distractions your way, a nosy neighbour, a bus driver who refuses to give you your change, or that colleague testing your patience. Keeping your peace takes intention, and turning off the noise and staying on course requires an act of devotion.

Fasting is meant to create a quiet space in your life, but if that space isn’t filled with something meaningful, old habits can creep back in. Sustaining that focus requires reinforcement beyond physical gatherings, and one way to do so is to tune in to faith-based programming to remain spiritually aligned throughout the period and beyond.

On GOtv, Christian channels such as Dove TV channel 113, Faith TV and Trace Gospel provide sermons, worship experiences and teachings that echo what is being practised in churches across the country.

From intentional conversations on Faith TV on GOtv channel 110 to true worship on Trace Gospel on channel 47, these channels provide nurturing content rooted in biblical teaching, worship, and life application. Viewers are met with inspiring sermons, reflections on scripture, and worship sessions that help form a rhythm of devotion. During fasting periods, this kind of consistent spiritual input becomes a source of encouragement, helping believers stay anchored in prayer and mindful of God’s presence throughout their daily routines.

To catch all these channels and more, simply subscribe, upgrade, or reconnect by downloading the MyGOtv App or dialling *288#. You can also stream anytime with the GOtv Stream App.

Plus, with the We Got You offer, available until 28th February 2026, subscribers automatically upgrade to the next package at no extra cost, giving you access to more channels this season.

Feature/OPED

Turning Stolen Hardware into a Data Dead-End

By Apu Pavithran

In Johannesburg, the “city of gold,” the most valuable resource being mined isn’t underground; it’s in the pockets of your employees.

With an average of 189 cellphones reported stolen daily in South Africa, Gauteng province has become the hub of a growing enterprise risk landscape.

For IT leaders across the continent, a “lost phone” is rarely a matter of a misplaced device. It is frequently the result of a coordinated “snatch and grab,” where the hardware is incidental, and corporate data is the true objective.

Industry reports show that 68% of company-owned device breaches stem from lost or stolen hardware. In this context, treating mobile security as a “nice-to-have” insurance policy is no longer an option. It must function as an operational control designed for inevitability.

In the City of Gold, Data Is the Real Prize

When a fintech agent’s device vanishes, the $300 handset cost is a rounding error. The real exposure lies in what that device represents: authorised access to enterprise systems, financial tools, customer data, and internal networks.

Attackers typically pursue one of two outcomes: a quick wipe for resale on the secondary market or, far more dangerously, a deep dive into corporate apps to extract liquid assets or sellable data.

Clearly, many organisations operate under the dangerous assumption that default manufacturer security is sufficient. In reality, a PIN or fingerprint is a flimsy barrier if a device is misconfigured or snatched while unlocked. Once an attacker gets in, they aren’t just holding a phone; they are holding the keys to copy data, reset passwords, or even access admin tools.

The risk intensifies when identity-verification systems are tied directly to the compromised device. Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), widely regarded as a gold standard, can become a vulnerability if the authentication factor and the primary access point reside on the same compromised device. In such cases, the attacker may not just have a phone; they now have a valid digital identity.

The exposure does not end at authentication. It expands with the structure of the modern workforce.

65% of African SMEs and startups now operate distributed teams. The Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) culture has left many IT departments blind to the health of their fleet, as personal devices may be outdated or jailbroken without any easy way to know.

Device theft is not new in Africa. High-profile incidents, including stolen government hardware, reinforce a simple truth: physical loss is inevitable. The real measure of resilience is whether that loss has any residual value. You may not stop the theft. But you can eliminate the reward.

Theft Is Inevitable, Exposure is Not

If theft cannot always be prevented, systems must be designed so that stolen devices yield nothing of consequence. This shift requires structured, automated controls designed to contain risk the moment loss occurs.

Develop an Incident Response Plan (IRP)

The moment a device is reported missing, predefined actions should trigger automatically: access revocation, session termination, credential reset and remote lock or wipe.

However, such technical playbooks are only as fast as the people who trigger them. Employees must be trained as the first line of defence —not just in the use of strong PINs and biometrics, but in the critical culture of immediate reporting. In high-risk environments, containment windows are measured in minutes, not hours.

Audit and Monitor the Fleet Regularly

Control begins with visibility. Without a continuous, comprehensive audit, IT teams are left responding to incidents after damage has occurred.

Opting for tools like Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) allows IT teams to spot subtle, suspicious activities or unusual access attempts that signal a compromised device.

Review Device Security Policies

Security controls must be enforced at the management layer, not left to user discretion. Encryption, patch updates and screen-lock policies should be mandatory across corporate devices.

In BYOD environments, ownership-aware policies are essential. Corporate data must remain governed by enterprise controls regardless of device ownership.

Decouple Identity from the Device

Legacy SMS-based authentication models introduce avoidable risk when the authentication channel resides on the compromised handset. Stronger identity models, including hardware tokens, reduce this dependency.

At the same time, native anti-theft features introduced by Apple and Google, such as behavioural theft detection and enforced security delays, add valuable defensive layers. These controls should be embedded into enterprise baselines rather than treated as optional enhancements.

When Stolen Hardware Becomes Worthless

With POPIA penalties now reaching up to R10 million or a decade of imprisonment for serious data loss offences, the Information Regulator has made one thing clear: liability is strict, and the financial fallout is absolute. Yet, a PwC survey reveals a staggering gap: only 28% of South African organisations are prioritising proactive security over reactive firefighting.

At the same time, the continent is battling a massive cybersecurity skills shortage. Enterprises simply do not have the boots on the ground to manually patch every vulnerability or chase every “lost” terminal. In this climate, the only viable path is to automate the defence of your data.

Modern mobile device management (MDM) platforms provide this automation layer.

In field operations, “where” is the first indicator of “what.” If a tablet assigned to a Cape Town district suddenly pings on a highway heading out of the city, you don’t need a notification an hour later—you need an immediate response. An effective MDM system offers geofencing capabilities, automatically triggering a remote lock when devices breach predefined zones.

On Supervised iOS and Android Enterprise devices, enforced Factory Reset Protection (FRP) ensures that even after a forced wipe, the device cannot be reactivated without organisational credentials, eliminating resale value.

For BYOD environments, we cannot ignore the fear that corporate oversight equates to a digital invasion of personal lives. However, containerization through managed Work Profiles creates a secure boundary between corporate and personal data. This enables selective wipe capabilities, removing enterprise assets without intruding on personal privacy.

When integrated with identity providers, device posture and user identity can be evaluated together through multi-condition compliance rules. Access can then be granted, restricted, or revoked based on real-time risk signals.

Platforms built around unified endpoint management and identity integration enable this model of control. At Hexnode, this convergence of device governance and identity enforcement forms the foundation of a proactive security mandate. It transforms mobile fleets from distributed risk points into centrally controlled assets.

In high-risk environments, security cannot be passive. The goal is not recovery. It is irrelevant, ensuring that once a device leaves authorised hands, it holds no data, no identity leverage, and no operational value.

Apu Pavithran is the CEO and founder of Hexnode

Feature/OPED

Daniel Koussou Highlights Self-Awareness as Key to Business Success

By Adedapo Adesanya

At a time when young entrepreneurs are reshaping global industries—including the traditionally capital-intensive oil and gas sector—Ambassador Daniel Koussou has emerged as a compelling example of how resilience, strategic foresight, and disciplined execution can transform modest beginnings into a thriving business conglomerate.

Koussou, who is the chairman of the Nigeria Chapter of the International Human Rights Observatory-Africa (IHRO-Africa), currently heads the Committee on Economic Diplomacy, Trade and Investment for the forum’s Nigeria chapter. He is one of the young entrepreneurs instilling a culture of nation-building and leadership dynamics that are key to the nation’s transformation in the new millennium.

The entrepreneurial landscape in Nigeria is rapidly evolving, with leaders like Koussou paving the way for innovation and growth, and changing the face of the global business climate. Being enthusiastic about entrepreneurship, Koussou notes that “the best thing that can happen to any entrepreneur is to start chasing their dreams as early as possible. One of the first things I realised in life is self-awareness. If you want to connect the dots, you must start early and know your purpose.”

Successful business people are passionate about their business and stubbornly driven to succeed. Koussou stresses the importance of persistence and resilience. He says he realised early that he had a ‘calling’ and pursued it with all his strength, “working long weekends and into the night, giving up all but necessary expenditures, and pressing on through severe setbacks.”

However, he clarifies that what accounted for an early success is not just tenacity but also the ability to adapt, to recognise and respond to rapidly changing markets and unexpected events.

Ambassador Koussou is the CEO of Dau-O GIK Oil and Gas Limited, an indigenous oil and natural gas company with a global outlook, delivering solutions that power industries, strengthen communities, and fuel progress. The firm’s operations span exploration, production, refining, and distribution.

Recognising the value of strategic alliances, Koussou partners with business like-minds, a move that significantly bolsters Dau-O GIK’s credibility and capacity in the oil industry. This partnership exemplifies the importance of building strong networks and collaborations.

The astute businessman, who was recently nominated by the African Union’s Agenda 2063 as AU Special Envoy on Oil and Gas (Continental), admonishes young entrepreneurs to be disciplined and firm in their decision-making, a quality he attributed to his success as a player in the oil and gas sector. By embracing opportunities, building strong partnerships, and maintaining a commitment to excellence, Koussou has not only achieved personal success but has also set a benchmark for future generations of African entrepreneurs.

His journey serves as a powerful reminder that with determination and vision, success is within reach.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn