Education

The Impact of Smaller Classes on Education

By Zubair Suliman

We’re often told that education is the best way out of poverty, but for many in Sub-Saharan Africa, the path out is often broken, especially for those who need an escape route the most.

There are many reasons why education barriers in the sub-region persist. For one, enrollment levels remain a problem. World Bank economists found that more than one in five primary school-aged children in Sub-Saharan Africa weren’t in school last year. And, according to ISS African Futures, once kids are in school we also battle to keep them there.

Despite progress made since the Education for All movement in the 1990s, there are still too few teachers to cater for the growing student population, according to the Common Wealth of Learning – resulting in lower engagement time with individuals and higher workloads for teachers. The 2023 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) progress report lays bare just how far behind the world is falling in achieving quality education for all.

Without more investment, only one in six countries will reach the target of getting all its adults to finish secondary school. A goal which, according to UNESCO, if achieved, could reduce global poverty by half. The SDG progress report indicates that more capital is also needed to close the nearly $100 billion yearly financing gap that lower and middle-income countries face. Without this funding, SDG education targets will remain unattainable.

But where should we invest to make the biggest impact on learner retention and outcomes? With time running out to meet UN goals to end poverty and promote prosperity, let’s look at the funding channels which have the most influence on a child’s school day for solutions.

Improve the daily school experience

Researchers for the International Journal of Educational Research analysed just under two decades of peer-reviewed research to understand what kinds of projects resulted in benefits for school kids.

Interestingly, the amount of money available to a school doesn’t necessarily correlate with student performance on “learning outcomes” such as reading for comprehension or their understanding of mathematics and science.

According to the ISS African Futures, interventions that can change a child’s daily school experience in a meaningful way make a huge difference because such projects can shield pupils from factors such as lack of desks, textbooks and equipment that can make learning more difficult.

Infrastructure projects, student performance incentives and support for teachers and their teaching methods were all among the ‘best buys’ for education.

Learners at electrified schools, for example, get better grades because they can study for longer on dark days or in after-school programmes. According to a paper published in Science Direct, scholarships can motivate students by exposing them to opportunities they wouldn’t otherwise have known about. They also help alleviate the cost of education, even in countries like Uganda where primary school is free but parents still struggle to afford uniforms and books.

The quality of the lessons children have also plays a huge role in how well they do. Schools with teachers that have greater knowledge of the subjects they teach, tend to produce students with better grades.

Smaller classes, more trained teachers, better outcomes

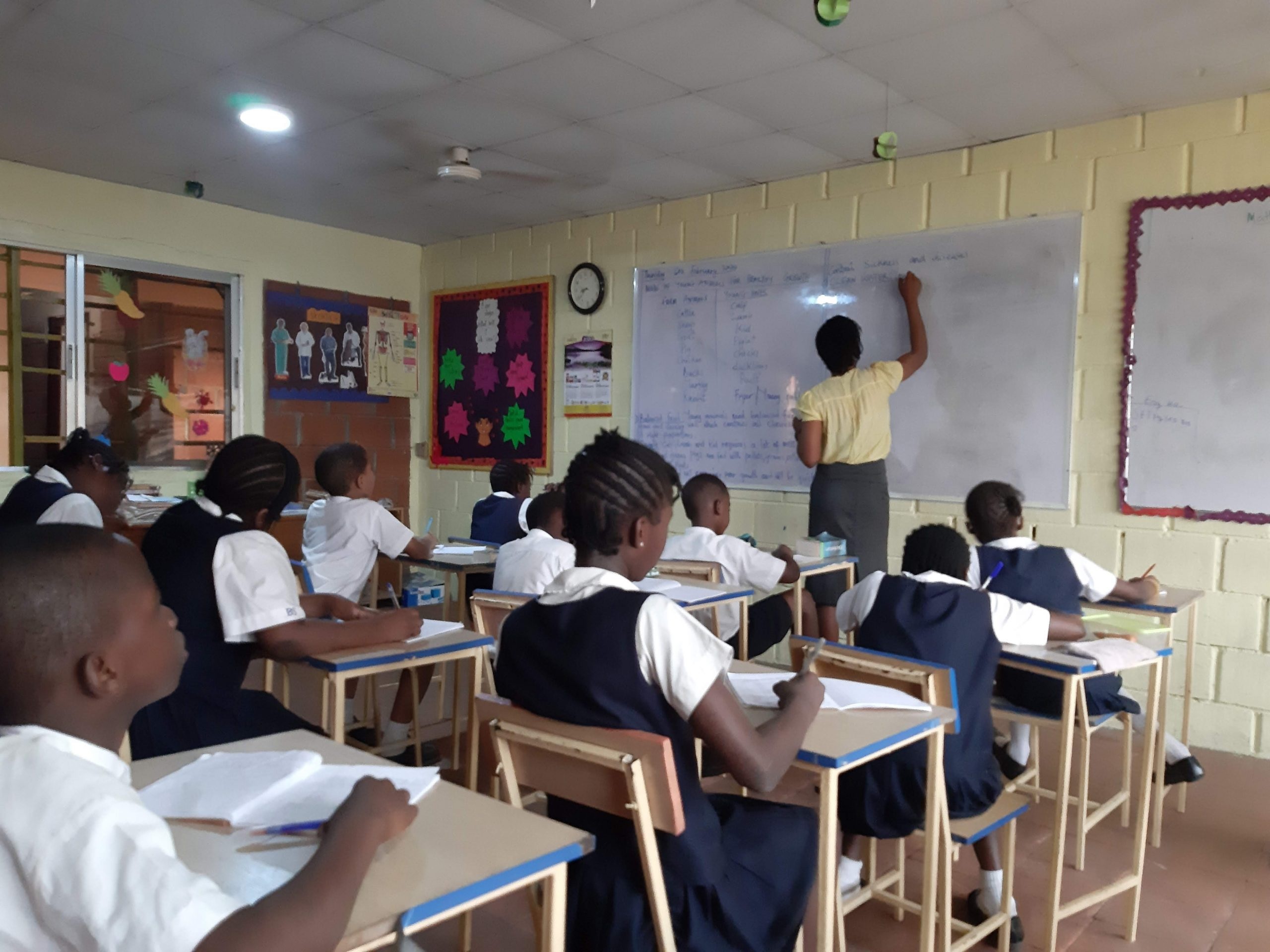

Class sizes impact both learning and a teacher’s willingness to stay at that school. Smaller classes allow educators to address individual challenges and go beyond just delivering educational content.

The student-to-teacher ratio measures the number of students per teacher in a class. Malawi and Tanzania have some of the highest ratios (55:1 and 57:1, respectively), while Botswana has the lowest.

According to the Litera Centre, optimal ratios vary based on economic and population factors. Lower ratios often mean teachers have a better understanding of student interests, goals and struggles enabling timely interventions to improve academic performance. When combined with teachers who have advanced subject knowledge, lower ratios can provide even more meaningful support to pupils.

Investing in impact

Norsad has invested nearly $40 million in social infrastructure services to improve education on the continent. Our investment partner Nova Pioneer schools, with their low student-to-teacher ratios, demonstrate the positive effects of this approach. Across 13 campuses in Kenya and South Africa, 4 400 learners benefit from two teachers in every classroom.

This structure allows teachers to focus on developing both problem-solving and soft skills, equipping learners for the knowledge economy. Teachers are trained as facilitators who encourage student-led solutions, fostering critical thinking skills in every class. Learners get a solid foundation in developing skills aligned with the fourth SDG: providing young adults with relevant skills for 21st-century jobs.

Facilities like school labs amplify the impact of this learning model, enabling exploration rather than rote memorisation and this can foster innovation skills necessary for modern careers. In these times interpersonal skills aren’t just nice to have, they are foundational.

“You can expect your voice to be heard,” said one student when asked how Nova Pioneer is different from other schools. This matters because “you start believing in yourself and the things that you can do,” she says.

Unlocking potential

Despite lagging progress on the education SDG targets, immense potential remains. As research shows – investments in infrastructure and human resources that directly improve students’ school day lead to better learning outcomes. From reading comprehension to coding and robotics skills, impact investing can help close critical skills gaps, reduce poverty and gender inequality and promote prosperity.

This International Day of Education, let’s strengthen our partnerships and turn to tactical investments so we can build a better, more equal Africa.

Education

Nigeria Secures $552m World Bank–Backed Boost for Basic Education

By Adedapo Adesanya

Nigeria has unlocked $552 million under the HOPE-EDU programme to fast-track reforms in the country’s basic education sector, in what has been described as the fastest activation of education financing of such scale in the nation’s history.

The HOPE-EDU initiative, HOPE for Quality Basic Education for All, is co-financed by the World Bank and the Global Partnership for Education. It is structured as a results-driven intervention targeting improved learning outcomes, equitable access to education and stronger institutional capacity at the state level.

The funding, secured through the Federal Ministry of Education, is aimed at strengthening foundational learning, expanding access to quality basic education and reinforcing accountability systems across participating states.

The Minister of Education, Mr Tunji Alausa, said the milestone reflects the administration’s determination to reposition education as a pillar of national development under President Bola Tinubu.

This was disclosed in a statement by the Ministry’s Director of Press and Public Relations, Mrs Folasade Boriowo, on Tuesday.

“The unlocking of the $552 million HOPE-EDU funding in just 12 months represents the fastest activation of education financing of this scale in our history. It reflects clarity of vision, strong intergovernmental coordination, and our unwavering commitment to delivering measurable results for Nigerian children,” the Minister stated.

“Under the leadership of President Tinubu, we are demonstrating that reform can be decisive, accountable, and impactful. These resources will directly strengthen foundational learning, expand access, and reinforce system-wide accountability across participating states,” the statement added.

HOPE-EDU aligns with the Nigeria Education Sector Renewal Initiative (NESRI), a broader reform framework focused on transparency, measurable performance and sector-wide transformation.

The programme also complements other pillars of the reform agenda, including HOPE-Governance and HOPE-Primary Health Care, which seek to address systemic challenges in public financial management, service delivery and policy coordination in key social sectors.

The development comes amid increased budgetary commitment to education. Since 2022, federal allocation to the sector has risen by over 302 per cent, according to the ministry.

In the 2026 fiscal year, the government earmarked N3.520 trillion for education, the highest allocation to date, alongside increased sub-national funding to support state-level priorities and targeted interventions.

The ministry said the latest funding injection is expected to translate into tangible gains in foundational literacy and numeracy, teacher effectiveness, equitable school access and strengthened accountability mechanisms.

Education

NELFUND Extends Student Loan Application Deadline Amid Surge in Interest

By Adedapo Adesanya

The Nigerian Education Loan Fund (NELFUND) has announced an extension to the deadline for its student loan application portal following a notable rise in nationwide interest driven by ongoing awareness campaigns.

In a Monday statement signed by Mrs Oseyemi Oluwatuyi, the fund’s Director of Strategic Communications, the extension was necessitated after a public notice issued last week announcing the closure of the application portal on February 27, 2026.

Mrs Oluwatuyi expressed that the extension was approved due to strong responses from students and key stakeholders across the country, alongside a surge in applications and enquiries.

She stated that the extension window will allow additional time for eligible students to complete their submissions, stressing that further decisions regarding the timeline will be communicated by management in due course.

She wrote, “According to NELFUND, the extension is intended to support several categories of applicants, including students who require more time to complete their applications, prospective applicants who only recently learned about the scheme through nationwide sensitisation programmes, and institutions that have just begun the 2025/2026 academic session.

“It will also accommodate institutions that are yet to submit their verified student lists.”

The chief executive of NELFUND, Akintunde Sawyerr, reaffirmed the fund’s commitment to ensuring equitable access to higher education financing, explaining that the sensitisation activities carried out across Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones have significantly increased awareness and participation in the programme.

“In line with the fund’s mandate to expand access to tertiary education funding, the extension was approved to ensure all eligible students are given a fair opportunity to apply.

“NELFUND also advised institutions that have not yet commenced the 2025/2026 academic session to submit a formal request for an extension along with their approved academic calendar for review,” he stated.

“Students are encouraged to make use of the extended period to complete their applications through the official NELFUND portal before the application window eventually closes.

“The fund reaffirmed its commitment to transparency, accountability, and the delivery of sustainable student financing initiatives aimed at removing financial barriers to higher education in Nigeria,” he added.

NELFUND charges students and members of the public to contact NELFUND via email at in**@******ov.ng or visit its official social media platforms for further enquiries.

Education

Prodigy Finance Offers African Students $2,500 Scholarship

By Modupe Gbadeyanka

Up to $2,500 in scholarship support has been provided by Prodigy Finance for 10 African students, alongside application fee reimbursement for 100 applicants applying through NovaGrad, the education access platform of Prodigy Finance.

This scholarship includes two forms of support, from applying to enrolment, both accessed through NovaGrad.

First, tuition and living expense support of up to $2,500 per student for 10 students, where financial support clearly bridges the gap between receiving an offer and being able to enrol.

Awards are limited, and competitive students who demonstrate strong merit and genuine financial need, have a realistic shortlist of universities, and can submit a complete application through NovaGrad within the stated deadlines will be given priority. Shortlisted applicants may be asked to provide additional documentation to confirm eligibility and reimbursement details before support is issued.

Second, application fee support, providing application fee reimbursement up to $200 per student for students who submit their university applications through NovaGrad.

A total of 100 students will be selected for this opportunity. This support is issued as a reimbursement once the application submission is verified and accepted via the platform.

Applications submitted outside NovaGrad do not qualify. Students register or log in on NovaGrad, enter a valid waiver code if applicable, submit their university application via NovaGrad, and once verified, the reimbursement is processed.

Prodigy Finance has supported postgraduate students heading to some of the world’s leading universities for years. Its scholarship programmes are focused on where funding and guidance can make the biggest difference, and that focus shifts year to year, from India and Latin America to Africa, as well as established global markets.

“African students have consistently demonstrated exceptional ambition and academic strength. Over the years, we have seen students from across the continent succeed at some of the world’s top institutions.

“This scholarship gives them a focused opportunity, and NovaGrad helps bring clarity to every step around it,” the Global Chief Business Officer at Prodigy Finance, Sonal Kapoor, said.

Also commenting, the spokesperson for NovaGrad, Ms Mariana Alcocer, said, “African students are among the most talented we see, yet many still lack the exposure or networks that help others access global education. This programme is about recognising that talent and creating a pathway forward.”

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn