World

Russia’s Economic Influence Lags Behind its Geopolitical Rhetorics and Propaganda in Africa

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

With its Russia-Africa Partnership Forum Action Plan (2023-2026), approved finally as a working document by the Kremlin, Russia faces long meandering road, especially in implementing several bilateral agreements signed with African countries. While maneuvering around challenges and obstacles inside Africa, Russia has still not fixed concretely financial budget for development projects, and worse Russia’s financial institutions are unprepared to invest capital in Africa, reflecting comparative low dynamics in resetting its economic influence in Africa. Russia has, therefore, lags far behind its geopolitical rhetorics and propaganda.

On June 4, under the chairmanship of Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, a meeting of the Collegium of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation was held on the topic “Furthering Russia’s cooperation with Africa.” While the meeting underscoring the priority status of comprehensive relations with the African continent in line with the Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation approved by the President in 2023, it also reminded preparations for the second ministerial conference of the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum, scheduled to take place this year in an African state, which will serve as a key milestone ahead of the third Russia-Africa Summit in 2026.

After two historic Russia-Africa summits, several conferences and bilateral meetings intended to move Russia’s relations from stagnation to growth, from low-level to a higher stage within the context of geopolitical competition and rivalry, has hit institutional obstacles including political bureaucracy and lack of prioritizing the implementation of official policies. Russia’s decision to quit the investment landscape could largely be attributed African leaders inability to create favourable climate, un-preparedness to change rules and regulations for foreign corporate businesses to operate in Africa.

Despite its tectonic desire to raise investment in energy and food security, infrastructure and industrial projects, Russia has still lagged behind in implementing its Action Plan Agenda 2023-26 approved during St. Petersburg summit. Policy researchers and experts have also underlined the empirical fact that African leaders have to be blamed for Russian businesses quitting Africa. During these previous years of exploring the question of Russia’s economic presence and the long-term implications, the discovery has been fantastic and mixed, while at times presented some interesting complications and contradictions.

At least, since the first Russia-Africa summit held in 2019, Russia has significantly reset its focus on investing in Africa’s economy, engaged in appreciably resonating public relations. The loudest was the planned construction of nuclear energy plants in Burkina Faso located in West Africa, and in South Africa. Now African leaders, policymakers, business leaders and investors have started rethinking alternative dynamic development models within the context of changing situation in the global economy.

There are many contributing factors to the policy mindset. And moreover African leaders are establishing hidden leverages and adopting a new psychology towards success that are connected to economic development in the continent. A few studies have shown that African business directors entrepreneurial attitudes have changed these decades, in spite of the geopolitical challenges by moving away from reactive to proactive positions in order to improve bilateral situation with Europe and the United States.

The leaders are more concern over growing demographics, rising youth unemployment and social standing of the population. Across Africa, 50-60% of the population is below the age of 25, according to United Nations reports. Leaders are also worried over their political campaign promises and their economic manifestos delivered to the respective electorates, and consequently rhetoric and popular slogans usch as ‘international solidarity and friendship’ are now geopolitical tools of the past. Understandably, these are the stark realities of the present times.

Such emerging trends, as mentioned above, have far-reaching implications particularly for Russia. Under this circumstances, it could still develop an integrated strategies for re-asserting visible economic influence in Africa, but a few reports below equally have some negative connotations. In late May 2025, the Russian media Interfax reported, quoting the press service of Russian state bank VTB, that the shareholders of Banco VTB Africa voted at a general meeting to approve a decision to liquidate the bank. “Work is now being done with the regulator (the National Bank of Angola) to make the relevant decisions on the arrangements for working on the liquidation in accordance with the legislation of the Republic of Angola,” VTB said.

It was really anticipated as VTB first deputy CEO Dmitry Pyanov said, initially, in February that the Angolan subsidiary’s license was to be terminated finally in this summer. Report explicitly shows that VTB previously owned 50.1% of Banco VTB Africa and the president of Angolan state company Endiama, Antonio Carlos Sumbula owned the other 49.9%.

Worth noting here that VTB focuses on work in Russia and in countries with which there has a large volume of foreign trade, above all China, trade with which reached US$290 billion in 2022. In early March, Russia’s VTB head Andrei Kostin, also said in an interview with the French newspaper Les Echos, that the VTB would sell its subsidiary bank in Angola due to sanctions. VTB was one of the first to be added to the United States and European Union (EU) sanctions lists, which hit the bank’s international business hard, following the launch of the military operation in Ukraine in February 2022.

Similarly there is also the historical fact that Russia contributed tremendously during South Africa’s political struggle until it attained independence. The outlook of bilateral relations is excellent, both staunch members of BRICS association (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), but Russia’s low level of economic investment is noticeable. By comparison, Russia accounts for a paltry 2% of South Africa’s trade, while the United States, United Kingdom and the European Union account for a combined 35% – with China around 9%. Energy deficit has crippled industrial operations, often described as unjustifiable and unacceptable as South Africa waves its baton, signaling power, on international stage but currently experiencing the worst economic crisis of its history. South Africa and Russia have lately drawn criticisms, while the basic question focused on the reasons why Russia has terribly failed with the planned construction of nuclear power plants under former President Jacob Zuma.

Mark-Anthony Johnson noted in his opinion article of early August 2023, published in Business and Financial Times, that “South Africa risks becoming bankrupt for its relationship with Russia, which adds virtually nothing to the economy, state revenues, economic growth, job creation, socioeconomic stability and investor sentiment.” South Africa has been hit with problems ranging from energy deficits, collapsing industrial production and rising tensions among the large labour force.

Despite consistent assurances made by high-ranking Russian officials that Africa is “in the mainstream of Russia’s foreign policy” have not been substantiated by systematic practical activities, and worse serious lack of state support for sustaining effective Russia-African economic ties have necessitated the pulling out of a number of Russian companies from Africa.

Undoubtedly, a number of Russian companies have largely under-performed in Africa, which experts attributed due to multiple reasons. Most often, Russian investors strike important investment niches that still require long-term strategies and adequate country study. Grappling with reality, there are many investment challenges including official bureaucracy in Africa.

In order to ensure business safety and consequently realize the target goals, it is necessary to attain some level of understanding the priorities of the country, investment legislations, comply with terms of agreement and a careful study of policy changes, particularly when there are sudden changes in government. It is important to study the African market structure, the investment climate, the capabilities of potential business partners and the characteristics of African customers.

In an analytical study, it is clear that Asian states, Europe and the United States often refer to Africa as the continent of the 21st century. Then a further general analysis shows that corporate Russian companies have shown interests in investing in the region. In practical terms, those corporate companies that managed, at least, to make inroads there, a few have already exited citing “technical and operational” reasons. At the same time, the business leaders demonstrated negative attitude towards Africa.

Several reports further confirmed that Russia has abandoned its lucrative platinum project contract that was signed for US$3 billion in September 2014, the platinum mine in the sun-scorched location about 50 km northwest of Harare, the Zimbabwean capital. Reasons for the abrupt termination of the bilateral contract have still not been made public, but Zimbabwe’s Centre for Natural Resource Governance pointed to lack of capital (source of finance)for the project.

Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov launched the US$3 billion Russian project back in 2014, after years of negotiations, with the hope of raising its economic profile in Zimbabwe. The development of the platinum deposit in Darwendale involves a consortium consisting of the Rostekhnologii State Corporation, Vneshekonombank and Vi Holding in a joint venture with some private Zimbabwe investors as well as the Zimbabwean government.

According to Bloomberg, the Darwendale has been tied to Russia since 2006, when former Zimbabwe president, Robert Mugabe, took the concession from a local unit of South Africa’s Impala Platinum Holdings and handed it over to Russian investors. The first venture to try and tap the deposit was named Ruschrome Mining – it included a state-owned mining company, the Zimbabwe Mining Development Corp., Russian defence conglomerate Rostec, Vnesheconombank and Vi Holding.

The Darwendale project was not tendered, according to available information from official government website sources monitored both in Russia and Zimbabwe. With its cordial relations, Russia was simply offered the lucrative mining concession without participating in any tender. After the project launch, Brigadier General Mike Nicholas Sango, Zimbabwe’s Ambassador to the Russian Federation, told me in an email that “Russia’s biggest economic commitment to Zimbabwe to date was its agreement in September 2014 to invest US$3 billion in what is Zimbabwe’s largest platinum mine”.

“What will set this investment apart from those that have been in Zimbabwe for decades is that the project will see the installation of a refinery to add value, thereby creating more employment and secondary industries. We are confident that this is just the start of a renewed Russian-Zimbabwean economic partnership that will blossom in coming years. The two countries are discussing other mining deals in addition to energy, agriculture, manufacturing and industrial projects,” Ambassador Sango added.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa said his government would soon open up the platinum sector to all interested foreign investors. Zimbabwe has the world’s second-largest platinum reserves after South Africa. With the rapidly geopolitical changes, Mnangagwa has been committed to opening up Zimbabwe’s economy to the rest of the world in order to attract the much-needed foreign direct investment to revive the ailing economy and make maximum use of the opportunities for bolstering and implementing a number of large projects in the country. That Zimbabwe would undergo a “painful” reform process to achieve transformation and modernisation of the economy.

Zimbabwe has various sectors besides mining. There is a possibility of greater participation of Russian economic actors in the development processes in Zimbabwe, and wider in southern Africa. Most often officials speak about Russia, claiming that Zimbabwe has had good and time-tested relations from Soviet days. Diplomatic relations between Zimbabwe and Russia already marked the 40th year and yet not a single industrial facility to boast of in that country. Zimbabwe is a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Prior to holding the first Russia-Africa summit, Norilsk Nickel terminated its deal with Botswana’s BCL Group. According to TASS News Agency, quoting the company’s media release in December 2018, Norilsk Nickel terminated its agreement to sell African assets to Botswana’s BCL Group, including a 50% stake in the Nkomati joint venture.

It said that the Russian company would seek damages from the BCL Group for the losses it suffered due to BCL’s failure to meet the terms of the agreement. The termination of the agreement would also enable Norilsk Nickel to pursue its own strategy for the African assets, Michael Marriott, Norilsk Nickel Africa’s Chief Executive, said as quoted by the press service.

In East African region, Russia’s RT-Global Resources and Rosneft quitted Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s oil refinery project and many major infrastructure deals. Russia had pledged US$4 billion but later disagreements over terms and frustration over in-fighting, intrigue and lobbying forced them to pull out of the country. The Ugandan government team noted that the Russian consortium exhibited inadequate assurance and availability of preferred alternative foreign contractors with comparatively high bidding terms.

Museveni, at first, favored the Russians because, apart from considering access to weapons, the Ugandan leadership was also counting on Russia’s world superiority as a counterweight to both western powers; mainly America and China. With Russians and the South Koreans out of the negotiations, Uganda appeared somewhat desperate, that was back in 2014.

Similarly to remind that Rosneft also abandoned its interest in the southern Africa oil pipeline construction, soon after its delegation in Angola had discussed the possible participation of the Kremlin-controlled company in exploration and development projects there. That project never appeared despite Russia has excellent relations with Angola, Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe. From business and political perspectives, the region is considered as a unique regional power put together with South Africa.

In addition, Lukoil, one of the Russia’s biggest oil companies, like many Russian companies, has had a long history of shuttling, forward and backward, with declaration of business intentions in tapping into oil and gas resources in Africa. Besides technical and geographical hitches, Lukoil noted explicitly in an official report on its website that “the African leadership and government policies always pose serious problems to operations in the region.” It said that the company has been ready to observe strictly its obligations as a foreign investor in Africa.

Lukoil pulled out of the oil and gas exploration and drilling project that it began in Sierra Leone. According to Interfax, the local Russian news agency, the company did not currently have any projects and has backed away due to poor exploration results in Sierra Leone. It was reported that drilling in West Africa, including in Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Sierra Leone, did not bring Lukoil the expected results, as preliminary technical results did not demonstrated commercial hydrocarbon reserves. Vice-President Leonid Fedun ruled Lukoil’s complete withdrawal from almost all projects in West Africa.

In the context of geopolitical changes, Russia’s corporate interest in exploring Africa’s oil and gas has consistently risen beyond its practical action. Understandably while Russia claims the world’s leading position as exporter of oil resources, it has, at the same time, expressing the desire to cooperate with potential African producers. Energy experts and energy analysts have explained Russia would only ‘gatekeep’ African producers from entry into the oil market. Russia exports crude oil and other oil-related products to a number of African countries, earned revenue to its state budget.

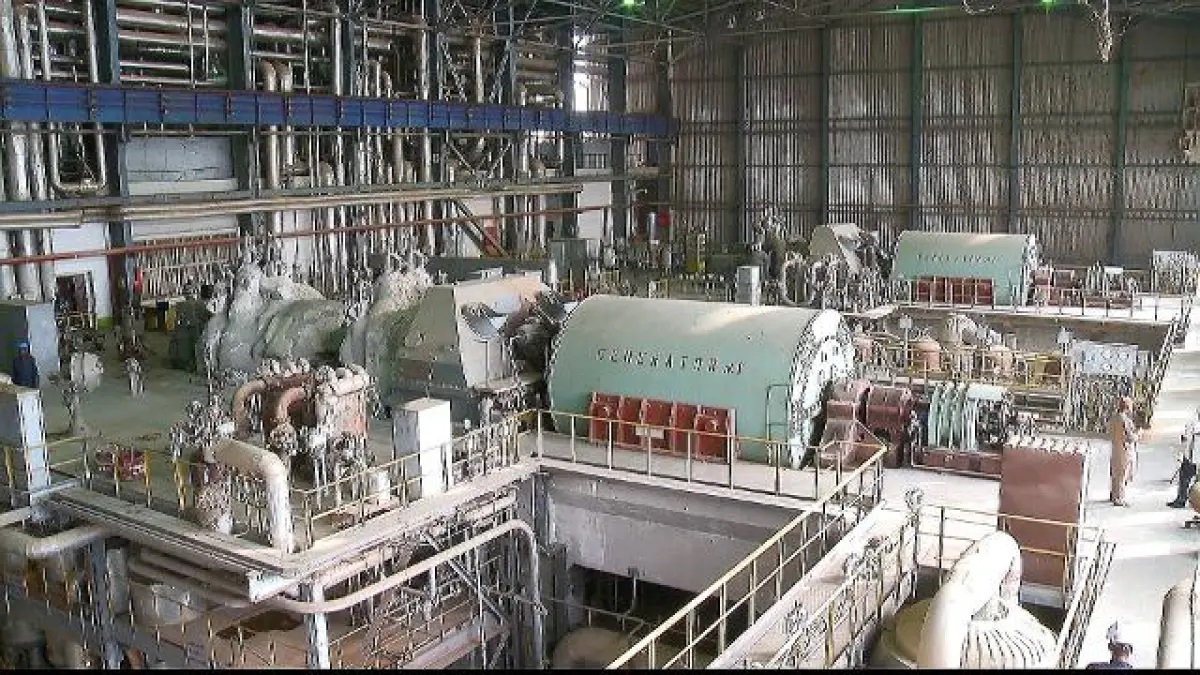

Under the aegis of resetting its bilateral economic relations with Nigeria, Russians along the line declared to revamp the Ajaokuta Iron and Steel Complex that was abandoned after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and further wanted to take up energy, oil and gas projects, as well as facilitate bilateral trade.

Nigeria is one of the Africa’s fastest growing economies and it boosts the largest population. It is currently estimated at 220 million people, and this is more or less a huge market potential for prospective foreign investors, further presents many investment opportunities.

Foreign Minister Lavrov held a review meeting with his Nigerian counterpart Minister Chief Ojo Mbila Maduekwe and emphatically noted that Moscow was prepared to offer trade preferences to Nigeria. Then, Vice President Kashim Shettima headed the Nigerian delegation to attend that second Russia-Africa summit in St Petersburg.

Foreign Minister Yusuf Maitama Tuggar was among the group. Following that, Maitama Tuggar again held talks in March 2024 at the Foreign Ministry. But it conclusively showed, Russia terribly failed to grant ‘trade preference’ it had promised during several Russian-Nigerian bilateral meetings on Smolenskiy Plochad.

Until today, Russia, as a reliable partner, has never honoured its promise of extending trade preferences, in practical terms, to Nigeria. Extending trade preferences was interpreted as an integral part of strengthening bilateral economic and trade cooperation between the two countries.

As well known, Russia has been prospecting for its nuclear-power ambitions down the years. According to Russia’s Rosatom, signed a protocol on nuclear that offered the possibility of bilateral cooperation for the development of nuclear infrastructure and the joint exploration and exploitation of uranium deposits. It was not considered as charity. Nigeria is also an economic powerhouse in West African region. The primary aim, two nuclear plants estimated cost at US$20 billion – the bulk of it by Russia, is to boost Nigeria’s electricity supply.

In addition, Russia’s second-largest oil company, and privately controlled Lukoil, as always, planned to expand its operations in Nigeria, and in a number of West African countries. Until writing this article, there has been a dead silence after Gazprom, the Russian energy giant, signed an agreement with the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) on the exploration and exploitation of gas reserves with a new joint venture company known as NiGaz Energy Company. Nigeria needs Russian technology to boost industrialization just as Russia needs Nigeria as a market for its industrial products and all kins of military equipment and weaponry. There is an explicit indication the two countries have sufficient and adequate perception of each other, but both grossly lack the required political will to implement existing bilateral agreements.

Over the years, Russian trade experts and business consultants have been discussing ways to improve economic cooperation with Africa. One analytical report indicated that a number of large Russian companies operating in Africa managed to establish themselves negatively in African countries. This is primarily due to ignorance of cultural peculiarities of the region, lack of social responsibility, failure to completely fulfill contractual obligations. These cases damage the image of Russia and Russian companies with entering the African market.

All these developments, more or less, have degraded Russia’s image of Doing Business in Africa. In December 2018, a year prior to the first African leaders gathering in Sochi, the Valdai Discussion Club hosted an expert discussion on Africa. Oleg Barabanov, Program Director of the Valdai Discussion Club, highlighted the investment prospects and their influence by foreign players, and further analyzed perspectives and challenges for potential Russian investors.

In her contribution, Nataliya Zaiser, Chairperson of the Board of the African Business Initiative (ABI) – a Moscow based business NGO, stressed that economic cooperation with African countries is not only an initiative, but also a response to request from African partners. Despite this mutual bilateral interest and potentially fruitful projects, Nataliya Zaiser said that there were still only few really successful Russian business cases on the continent.

Andrei Maslov, Coordinator of the work/project on the Russia Africa Shared Vision 2030 report, Integration Expertise Analytical Centre, explained in comparison with the situation a decade ago, that Africa is not only the main initiator of dialogue with Russia, but it is much more ready for it. If earlier the economic landscape of the continent was determined by Western companies with their colonial approaches, now Africa is ready to become an equal partner, according to the Valdai report.

However, there are problems: Maslov echoed Nataliya Zaiser by saying that about 90% of the projects end in failure. In order to overcome this discord, the coordinating role of the state is needed, which, together with the private business, should prepare a clear-cut roadmap and set targets for the development of various industries. The driver of economic cooperation, according to Maslov, can be private rather than top-down state initiatives.

“For us, Africa is not a terra incognita: the USSR actively worked there, having diplomatic relations with 35 countries. In general, there are no turns, reversals or zigzags in our policy. There is a consistent development of relations with African countries,” according to Oleg Ozerov from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation.

Signing bilateral agreements is not absolutely the best ultimate guarantee to the success of investment, however it provides legal basis. As the situation develops and interest continues to rise, Russian investors have to make part of the financial budget for private consultancy services, as many foreign players do, and be prepared to learn more about the culture of investing in Africa.

According to expert policy narratives, Russian-African economic cooperation and partnerships continue to face challenges and obstacles, including inadequate knowledge of the Africa’s investment landscape and lack of appreciable state support, while Moscow seems to increasingly prioritize anti-Western rhetoric and political confrontation in the context of the great power competition in Africa. African leaders largely prefers to play neutral positions and act in strategic balancing ways.

In this final summary, a thorough research shows Russian companies have been exiting Africa primarily due to geopolitical shifts, economic challenges, and changing investment climate. This trend has to be drastically reversed, and rather invigorate multifaceted relations. As practical matter of facts, Russia’s decision would be in the right direction in connection with allocating financial resources for specific projects by setting up a Development Fund under the African Partnership Department at Russia’s Foreign Ministry. This ultimate step offers possibility to gain the status as a recognizable key player in the continent. And in this case, Russia’s investment partnerships and its dominating economic collaborations would become more visible in future across Africa. Russia has, therefore, lagged far behind its geopolitical rhetorics and propaganda

Kestér Kenn Klomegâh has a diverse work experience in the field of policy research and business consultancy. His focused interest includes geopolitical changes, foreign relations and economic development related questions in Africa with key global powers.

World

African Visual Art is Distinguished by Colour Expression, Dynamic Form—Kalalb

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

In this insightful interview, Natali Kalalb, founder of NAtali KAlalb Art Gallery, discusses her practical experiences of handling Africa’s contemporary arts, her professional journey into the creative industry and entrepreneurship, and also strategies of building cultural partnership as a foundation for Russian-African bilateral relations. Here are the interview excerpts:

Given your experience working with Africa, particularly in promoting contemporary art, how would you assess its impact on Russian-African relations?

Interestingly, my professional journey in Africa began with the work “Afroprima.” It depicted a dark-skinned ballerina, combining African dance and the Russian academic ballet tradition. This painting became a symbol of cultural synthesis—not opposition, but dialogue.

Contemporary African art is rapidly strengthening its place in the world. By 2017, the market was growing so rapidly that Sotheby launched its first separate African auction, bringing together 100 lots from 60 artists from 14 foreign countries, including Algeria, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, and others. That same year during the Autumn season, Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris hosted a major exhibition dedicated to African art. According to Artnet, sales of contemporary African artists reached $40 million by 2021, a 434% increase in just two years. Today, Sotheby holds African auctions twice a year, and in October 2023, they raised $2.8 million.

In Russia, this process manifests itself through cultural dialogue: exhibitions, studios, and educational initiatives create a space of trust and mutual respect, shaping the understanding of contemporary African art at the local level.

Do you think geopolitical changes are affecting your professional work? What prompted you to create an African art studio?

The international context certainly influences cultural processes. However, my decision to work with African themes was not situational. I was drawn to the expressiveness of African visual language—colour, rhythm, and plastic energy. This theme is practically not represented systematically and professionally in the Russian art scene.

The creation of the studio was a step toward establishing a sustainable platform for cultural exchange and artistic dialogue, where the works of African artists are perceived as a full-fledged part of the global cultural process, rather than an exotic one.

To what extent does African art influence Russian perceptions?

Contemporary African art is gradually changing the perception of the continent. While previously viewed superficially or stereotypically, today viewers are confronted with the depth of artistic expression and the intellectual and aesthetic level of contemporary artists.

Portraits are particularly impactful: they allow us to see not just an abstract image of a “continent,” but a concrete personality, character, and inner dignity. Global market growth data and regular auctions create additional trust in African contemporary art and contribute to its perception as a mature and valuable movement.

Does African art reflect lifestyle and fashion? How does it differ from Russian art?

African art, in my opinion, is at its peak in everyday culture—textiles, ornamentation, bodily movement, rhythm. It interacts organically with fashion, music, interior design, and the urban environment. The Russian artistic tradition is historically more academic and philosophical. African visual art is distinguished by greater colour expression and dynamic form. Nevertheless, both cultures are united by a profound symbolic and spiritual component.

What feedback do you receive on social media?

Audience reactions are generally constructive and engaging. Viewers ask questions about cultural codes, symbolism, and the choice of subjects. The digital environment allows for a diversity of opinions, but a conscious interest and a willingness to engage in cultural dialogue are emerging.

What are the key challenges and achievements of recent years?

Key challenges:

- Limited expert base on African contemporary art in Russia;

- Need for systematic educational outreach;

- Overcoming the perception of African art as exclusively decorative or ethnic.

Key achievements:

- Building a sustainable audience;

- Implementing exhibition and studio projects;

- Strengthening professional cultural interaction and trust in African

contemporary art as a serious artistic movement.

What are your future prospects in the context of cultural diplomacy?

Looking forward, I see the development of joint exhibitions, educational programs, and creative residencies. Cultural diplomacy is a long-term process based on respect and professionalism. If an artistic image is capable of uniting different cultural traditions in a single visual space, it becomes a tool for mutual understanding.

World

Ukraine Reveals Identities of Nigerians Killed Fighting for Russia

By Adedapo Adesanya

The Ukrainian Defence Intelligence (UDI) has identified two Nigerian men, Mr Hamzat Kazeem Kolawole and Mr Mbah Stephen Udoka, allegedly killed while fighting as Russian mercenaries in the war between the two countries ongoing since February 2022.

The development comes after Russia denied knowledge of Nigerians being recruited to fight on the frontlines.

Earlier this week, the Russian Ambassador to Nigeria, Mr Andrey Podyolyshev, said in Abuja that he was not aware of any government-backed programme to recruit Nigerians to fight in the war in Ukraine.

He said if at all such activity existed, it is not connected with the Russian state.

However, in a statement on Thursday, the Ukrainian Defence released photographs of Nigerians killed while defending Russia.

“In the Luhansk region, military intelligence operatives discovered the bodies of two citizens of the Federal Republic of Nigeria — Hamzat Kazeen Kolawole (03.04.1983) and Mbah Stephen Udoka (07.01.1988),” the statement read.

According to the statement, both men served in the 423rd Guards Motor Rifle Regiment (military unit 91701) of the 4th Guards Kantemirovskaya Tank Division of the armed forces of the Russian Federation.

UDI said that they signed contracts with the Russian Army in the second half of 2025 – the deceased Mr Kolawole on August 29 and Mr Udoka on September 28.

“Udoka received no training whatsoever — just five days later, on October 3, he was assigned to the unit and sent to the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine,” the report read.

It added that no training records for Mr Kolawole have been preserved; however, it is highly likely that he also received no military training, but his wife and three children remain in Nigeria.

Both Nigerians, the report added, were killed in late November during an attempt to storm Ukrainian positions in the Luhansk region.

“They never engaged in a firefight — the mercenaries were eliminated by a drone strike,” UDI stated, warning foreign citizens against travelling to the Russian Federation or taking up any work on the territory of the “aggressor state”.

“A trip to Russia is a real risk of being forced into a suicide assault unit and, ultimately, rotting in Ukrainian soil,” the statement read.

In an investigation earlier this month, CNN reported that hundreds of African men have been enticed to fight for Russia in Ukraine with the promise of civilian jobs and high salaries. However, the media organisation uncovered that they are being deceived or sent to the front lines with little combat training.

CNN said it reviewed hundreds of chats on messaging apps, military contracts, visas, flights and hotel bookings, as well as gathering first-hand accounts from African fighters in Ukraine, to understand just how Russia entices African men to bolster its ranks.

World

Today’s Generation of Entrepreneurs Value Flexibility, Autonomy—McNeal-Weary

By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

The Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI) is the United States’ signature step to invest in the next generation of African leaders. Since its establishment in 2010 by Obama administration, YALI has offered diverse opportunities, including academic training in leadership, governance skills, organizational development and entrepreneurship, and has connected with thousands of young leaders across Africa. This United States’ policy collaboration benefits both America and Africa by creating stronger partnerships, enhancing mutual prosperity, and ensuring a more stable environment.

In our conversation, Tonya McNeal-Weary, Managing Director at IBS Global Consulting, Inc., Global Headquarters in Detroit, Michigan, has endeavored to discuss, thoroughly, today’s generation of entrepreneurs and also building partnerships as a foundation for driving positive change and innovation in the global marketplace. Here are the excerpts of her conversation:

How would you describe today’s generation of entrepreneurs?

I would describe today’s generation of entrepreneurs as having a digital-first mindset and a fundamental belief that business success and social impact can coexist. Unlike the entrepreneurs before them, they’ve grown up with the internet as a given, enabling them to build global businesses from their laptops and think beyond geographic constraints from day one. They value flexibility and autonomy, often rejecting traditional corporate ladders in favor of building something meaningful on their own terms, even if it means embracing uncertainty and financial risk that previous generations might have avoided.

And those representing the Young African Leaders Initiative, who attended your webinar presentation late January 2026?

The entrepreneurs representing the Young African Leaders Initiative are redefining entrepreneurship on the continent by leveraging their unique perspectives, cultural heritage, and experiences. Their ability to innovate within local contexts while connecting to global opportunities exemplifies how the new wave of entrepreneurs is not confined by geography or conventional expectations.

What were the main issues that formed your ‘lecture’ with them, Young African Leaders Initiative?

The main issues that formed my lecture for the Young African Leaders Initiative were driven by understanding the importance of building successful partnerships when expanding into the United States or any foreign market. During my lecture, I emphasized that forming strategic alliances can help entrepreneurs navigate unfamiliar business environments, access new resources, and foster long-term growth. By understanding how to establish strong and effective partnerships, emerging leaders can position their businesses for sustainable success in global markets. I also discussed the critical factors that contribute to successful partnerships, such as establishing clear communication channels, aligning on shared goals, and cultivating trust between all parties involved. Entrepreneurs must be proactive in seeking out partners who complement their strengths and fill gaps in expertise or resources. It is equally important to conduct thorough due diligence to ensure that potential collaborators share similar values and ethical standards. Ultimately, the seminar aimed to empower YALI entrepreneurs with practical insights and actionable strategies for forging meaningful connections across borders. Building successful partnerships is not only a pathway to business growth but also a foundation for driving positive change and innovation in the global marketplace.

What makes a ‘leader’ today, particularly, in the context of the emerging global business architecture?

In my opinion, a leader in today’s emerging global business architecture must navigate complexity and ambiguity with a fundamentally different skill set than what was previously required. Where traditional leadership emphasized command-and-control and singular vision, contemporary leaders succeed through adaptive thinking and collaborative influence across decentralized networks. Furthermore, emotional intelligence has evolved from a soft skill to a strategic imperative. Today, the effective modern leader must possess deep cross-cultural intelligence, understanding that global business is no longer about exporting one model worldwide but about genuinely integrating diverse perspectives and adapting to local contexts while maintaining coherent values.

Does multinational culture play in its (leadership) formation?

I believe multinational culture plays a profound and arguably essential role in forming the kind of leadership required in today’s global business environment. Leaders who have lived, worked, or deeply engaged across multiple cultural contexts develop a cognitive flexibility that’s difficult to replicate through reading or training alone. More importantly, multinational exposure tends to dismantle the unconscious certainty that one’s own way of doing things is inherently “normal” or “best.” Leaders shaped in multicultural environments often develop a productive discomfort with absolutes; they become more adept at asking questions, seeking input, and recognizing blind spots. This humility and curiosity become strategic assets when building global teams, entering new markets, or navigating geopolitical complexity. However, it’s worth noting that multinational experience alone doesn’t automatically create great leaders. What matters is the depth and quality of cross-cultural engagement, not just the passport stamps. The formation of global leadership is less about where someone has been and more about whether they’ve developed the capacity to see beyond their own cultural lens and genuinely value differences as a source of insight rather than merely tolerating them as an obstacle to overcome.

In the context of heightening geopolitical situation, and with Africa, what would you say, in terms of, people-to-people interaction?

People-to-people interaction is critically important in the African business context, particularly as geopolitical competition intensifies on the continent. In this crowded and often transactional landscape, the depth and authenticity of human relationships can determine whether a business venture succeeds or fails. I spoke on this during my presentation. When business leaders take the time for face-to-face meetings, invest in understanding local priorities rather than imposing external agendas, and build relationships beyond the immediate transaction, they signal a different kind of partnership. The heightened geopolitical situation actually makes this human dimension more vital, not less. As competition increases and narratives clash about whose model of development is best, the businesses and nations that succeed in Africa will likely be those that invest in relationships characterized by reciprocity, respect, and long-term commitment rather than those pursuing quick wins.

How important is it for creating public perception and approach to today’s business?

Interaction between individuals is crucial for shaping public perception, as it influences views in ways that formal communications cannot. We live in a society where word-of-mouth, community networks, and social trust areincredibly important. As a result, a business leader’s behavior in personal interactions, their respect for local customs, their willingness to listen, and their follow-through on commitments have a far-reaching impact that extends well beyond the immediate meeting. The geopolitical dimension amplifies this importance because African nations now have choices. They’re no longer dependent on any single partner and can compare approaches to business.

From the above discussions, how would you describe global business in relation to Africa? Is it directed at creating diverse import dependency?

While it would be too simplistic to say global business is uniformly directed at creating import dependency, the structural patterns that have emerged often produce exactly that outcome, whether by design or as a consequence of how global capital seeks returns. Global financial institutions and trade agreements have historically encouraged African nations to focus on their “comparative advantages” in primary commodities rather than industrial development. The critical question is whether global business can engage with Africa in ways that build productive capacity, transfer technology, develop local talent, and enable countries to manufacture for themselves and for export—or whether the economic incentives and power irregularities make this structurally unlikely without deliberate policy intervention.

-

Feature/OPED6 years ago

Feature/OPED6 years agoDavos was Different this year

-

Travel/Tourism10 years ago

Lagos Seals Western Lodge Hotel In Ikorodu

-

Showbiz3 years ago

Showbiz3 years agoEstranged Lover Releases Videos of Empress Njamah Bathing

-

Banking8 years ago

Banking8 years agoSort Codes of GTBank Branches in Nigeria

-

Economy3 years ago

Economy3 years agoSubsidy Removal: CNG at N130 Per Litre Cheaper Than Petrol—IPMAN

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoSort Codes of UBA Branches in Nigeria

-

Banking3 years ago

Banking3 years agoFirst Bank Announces Planned Downtime

-

Sports3 years ago

Sports3 years agoHighest Paid Nigerian Footballer – How Much Do Nigerian Footballers Earn

Pingback: Has The Nigerian Government Blocked Trade Deals Between Russia And The Igbos? | NewsVerifierAfrica